[Author’s Note: This is Part 5 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 3 on foot and ankle mobility, Part 4 on knee mobility, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

[Author’s Note: This is Part 5 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 3 on foot and ankle mobility, Part 4 on knee mobility, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

We wrap up the performance-mobility series with a seldom-considered element of running mechanics, the trunk–the mid-section of the body, comprised primarily of the spine and rib cage–and its extensional mobility. Though last, it is certainly not least in its importance in performance and injury prevention. It all starts and ends at the trunk. It is the platform upon which our movers–the arms and legs–attach, and it contains our cardiovascular engine, the heart and lungs. As such, how this dynamic system moves has huge repercussions on how fast and far we can run.

Before you continue here, be sure to take a look back at Part 2 of this series where we also talked about trunk mobility, in that case, its rotational mobility. The metric addressed in that article is different from the metric we discuss in this one, though they both have to do with the body’s trunk. Part 2 is about the whole-body push off (measured by rotation), whereas this article is about hip power, arm efficiency, and breathing.

Neutral Trunk Alignment and Its Effects on Running

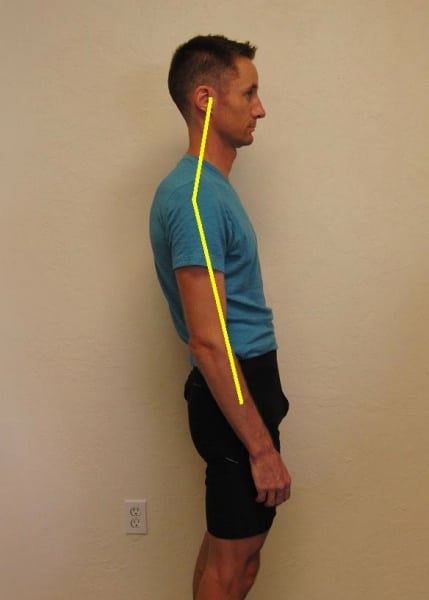

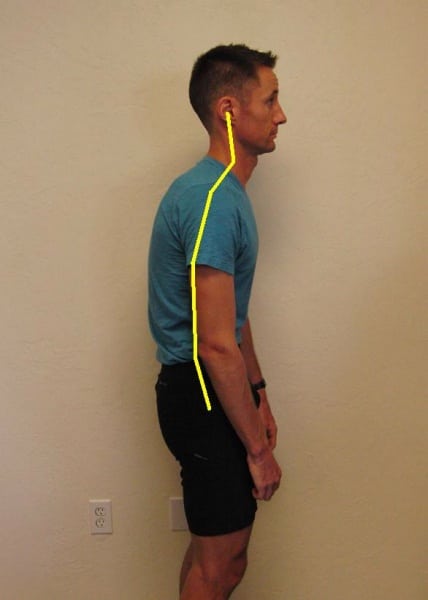

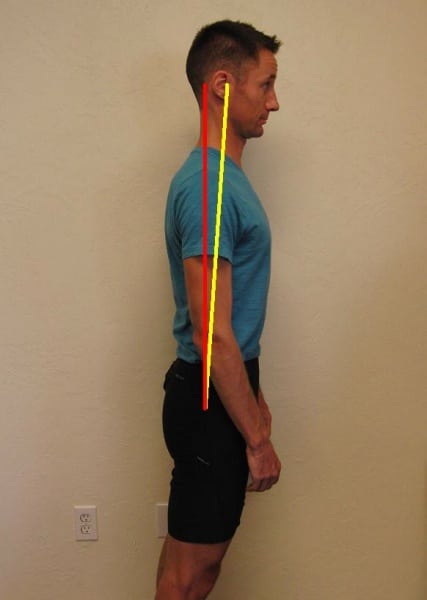

Several years ago I wrote a piece on trunk posture and its relationship to running economy. In it are a variety of pictures (unflattering of the author) demonstrating neutral versus inefficient trunk postures:

The ‘too tall’ torso position.

While useful, this article was one-dimensional. It focused only on the role trunk alignment plays in foot strike. In short, a neutral-aligned, forward-engaged trunk is required to ensure our foot lands beneath our body (or the ‘center of mass,’ the point at which our average body weight is located, usually in the middle or front of the trunk), limiting impact stress, and promoting maximum forward propulsion:

In totality, neutral-trunk alignment has at least four important impacts on efficient running:

- A neutral, forward trunk promotes efficient foot strike under the body’s center of mass. As discussed in the original trunk column, a neutral and forward trunk facilitates the foot landing beneath the body’s center of mass. This landing strategy limits braking forces.

- A neutral spine–with emphasis on spinal extension–orients the pelvis and hips behind us, to promote maximum hip extension and a powerful push-off. The alignment of the spine–forward-leaning and arching back–positions the pelvis beneath and behind us, which naturally sets up the hip to powerfully push behind. Conversely, standing either upright and/or rounded forward does the opposite. This keeps the pelvis forward and prevents efficient hip extension.

- A neutral and forward spine promotes an efficient, shoulder-blade-driven arm swing. Again, with a slightly extended spine, the shoulder blades are able to drive rearward and downward with arm swing. Because the shoulder blades are connected to the hip extensors, a shoulder-blade-driven arm swing creates additional power and efficiency magnifier–improving landing efficiency and overall running economy. This concept was discussed in a previous column on arm swing. However, if the trunk becomes too rounded, the shoulder blades become disengaged. Stuck forward (and usually upward), they no longer contribute to the hips, and significant power and efficiency is lost.

- A neutral trunk alignment is absolutely crucial in achieving maximum lung volume. This is the least-considered, but arguably most-crucial component of performance mobility anywhere in the system. The physiology of running is driven by the cardiovascular system, with the improvement of aerobic capacity at the crux of peak performance. Indeed, even anaerobic fitness depends on the expedient removal of carbon dioxide, even if our oxygen uptake (VO2Max) might be limited by other internal factors. As such, consider the idea that postural deficiencies can physically restrict lung volume and thus limit VO2Max and overall performance. Thinking mechanically, a neutral spine is required for maximal expansion of the rib cage, and with it, inflation of the lungs. Loss of neutral–being either too flexed (more common) or too extended–can ‘lock out’ maximum rib-cage expansion, limiting breath volume.

The author demonstrating neutral and forward trunk engagement with efficient hip extension and arm swing.

This is easy to test. In standing, first assume the ‘too tall’ position. Exhale fully, then inhale as deeply as possible. Note both the duration and overall volume of air you can inhale. Exhale again, then assume the ‘old man’ position. Again, inhale as deeply as possible. Lastly, find your best neutral: moderate curvature in the mid-to-low spine, with shoulders slightly rolled back. Once more, inhale. It is not uncommon to have measurable differences in inhalation volume of 30% or more when deviating from neutral spine! A tremendous difference.

Checking In: Mobility Metrics for Trunk Extension

Far and away the most common mobility restriction in the trunk is extension, or the ability to backward arch anywhere in the spine. As an adjunct, this also includes the ability of the shoulders to migrate posteriorly (to the point at which they can efficiently contribute to running).

This metric is quite simple, but informative of one’s ability to achieve neutral.

Details: Find a wall, unobstructed from the floor to head level. Then, very simply, place as much of your body against the wall: heels, pelvis, middle and upper back, and head. Then raise your arms overhead (a la Cactus Pose in yoga).

Goals:

- All points of the body, namely the upper back, shoulders, elbows and hands, should touch the wall.

Common Deficits:

- Inability to maintain the mid-back and shoulder blades on the wall: this usually indicates extension restriction in the mid-trunk.

- Inability to maintain the head against the wall (with chin level): usually indicative of upper-trunk stiffness.

- Inability to touch the elbows and hands to the wall: indicative of anterior chest and shoulder restriction.

Implications:

Range-of-motion loss in the trunk and shoulders–most commonly a restriction of trunk extension and chest opening (more often resulting from too much sitting during our non-running day)–can cause one or more deficits described above, including loss of landing efficiency, decreased hip extension push-off strength, inefficient arm swing, and, most notably, a significant decrease in lung volume.

Restorative Exercises for Trunk-Extension Mobility

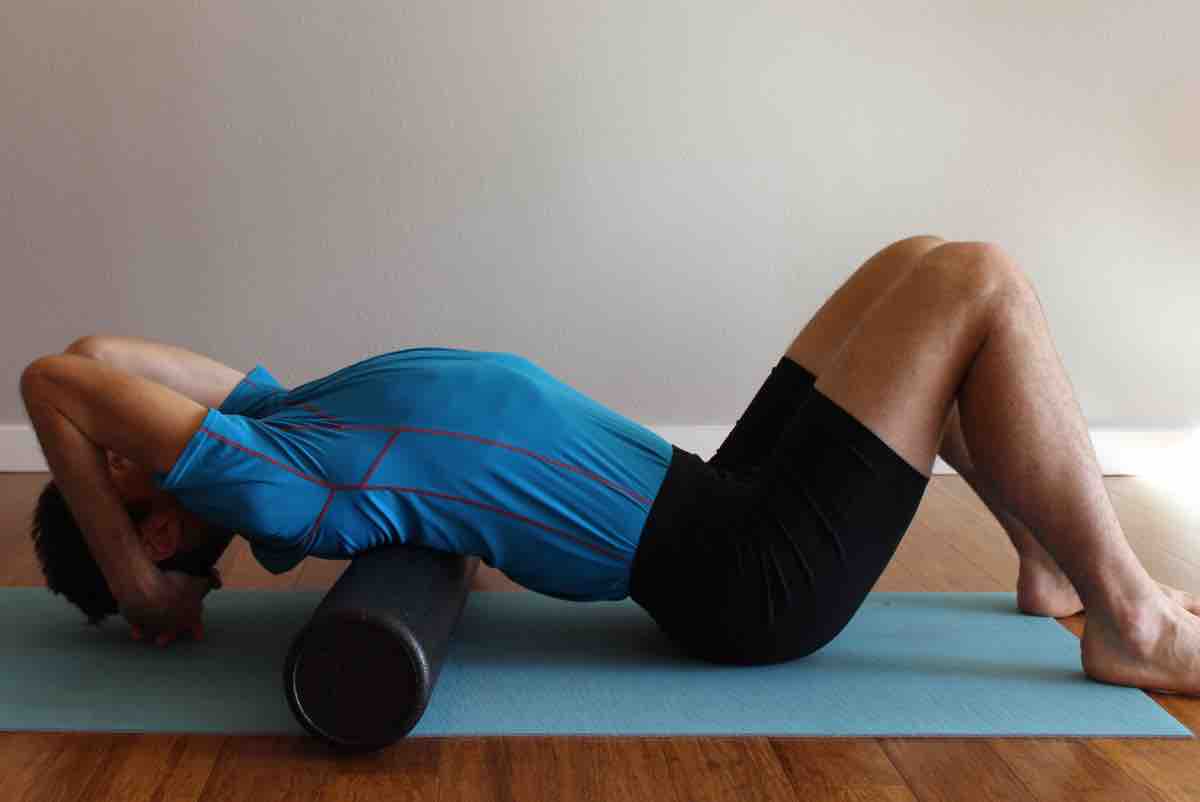

Foam-Roller Mobility

While most runners use them for leg-muscle massage, foam rollers provide the best way to restore spine and rib-cage mobility.

To perform: Trunk mobility can be addressed on the foam roller in a variety of positions: vertical, horizontal, or oblique angles. (See my previous column on foam rolling for a full description of the various positions.) For maximum trunk extension and chest opening, begin by positioning the roller horizontally. With knees bent and feet flat on the floor, and the head supported in the hands, carefully lie on top of the roll. Begin by rolling the length of your trunk in neutral: from the bottom of the neck (above the shoulder blades) to the bottom of the ribcage (avoid going into the lower back, which is both uncomfortable and unnecessary for most).

Roll slowly up and down for one to two minutes. Then, perform an ‘arch over:’ find a stiff spot (usually in the mid-trunk), then allow the pelvis to relax down to the floor. If tolerable, lower the hands so that the head and neck near the floor. Maintain this position for several breaths, then rise out of it. Find other stiff areas and repeat.

Trunk foam rolling is optimally performed daily, and is a great adjunct to other trunk stretches or a mobility-based yoga routine, including:

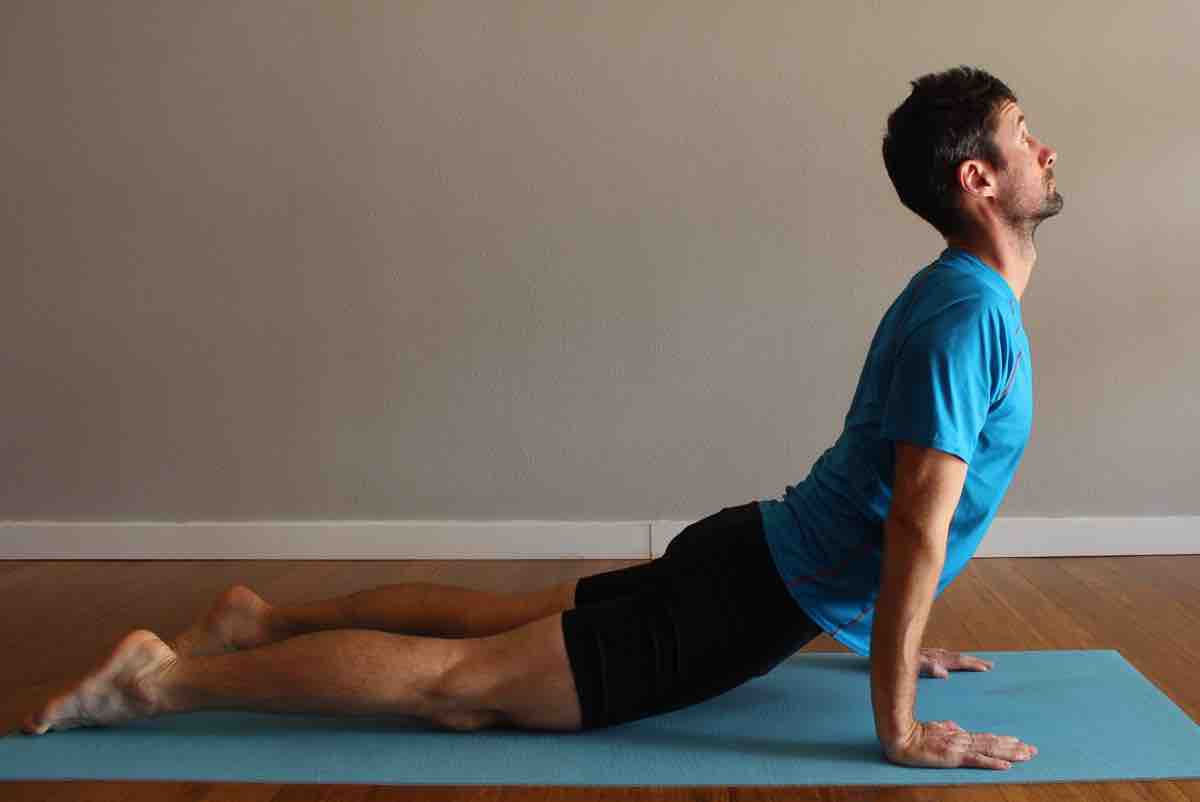

Upward Dog and Child’s Poses

Following the foam roller, try some Upward Dog Pose and Child’s Pose yoga positions to work on spinal mobility.

To perform: Begin in prone with your hands low (at or below chest level) and beside the trunk. Push upward and rearward, trying to drag your toes an inch or two forward into Upward Dog Pose. This creates a traction force, which helps open the space between spinal bones and facilitates greater stretch. Hold for one or two breaths.

Then carefully transition rearward into Child’s Pose, keeping the hands on the floor, gently sit back onto your heels. Keeping the hands forward creates a traction force here, too, and helps stretch open the chest. Hold the position for one to two breaths.

Transition to hand and knees, then lower to prone to repeat. Perform as few as three to five repetitions, once or twice daily, to facilitate improved trunk motion.

Trunk-Rotation Stretch

This exercise works on rotation and general rib-cage opening.

To perform: Lie supine on the floor. Flex a knee up to waist level, then fold it across the body. Maintain the same-sided elbow on the floor (with arm outstretched). The opposite hand pushes the knee to the floor. Perform with a prolonged hold or oscillating (on and off) force, for 10 to 60 seconds, one to six times per side, once or twice daily.

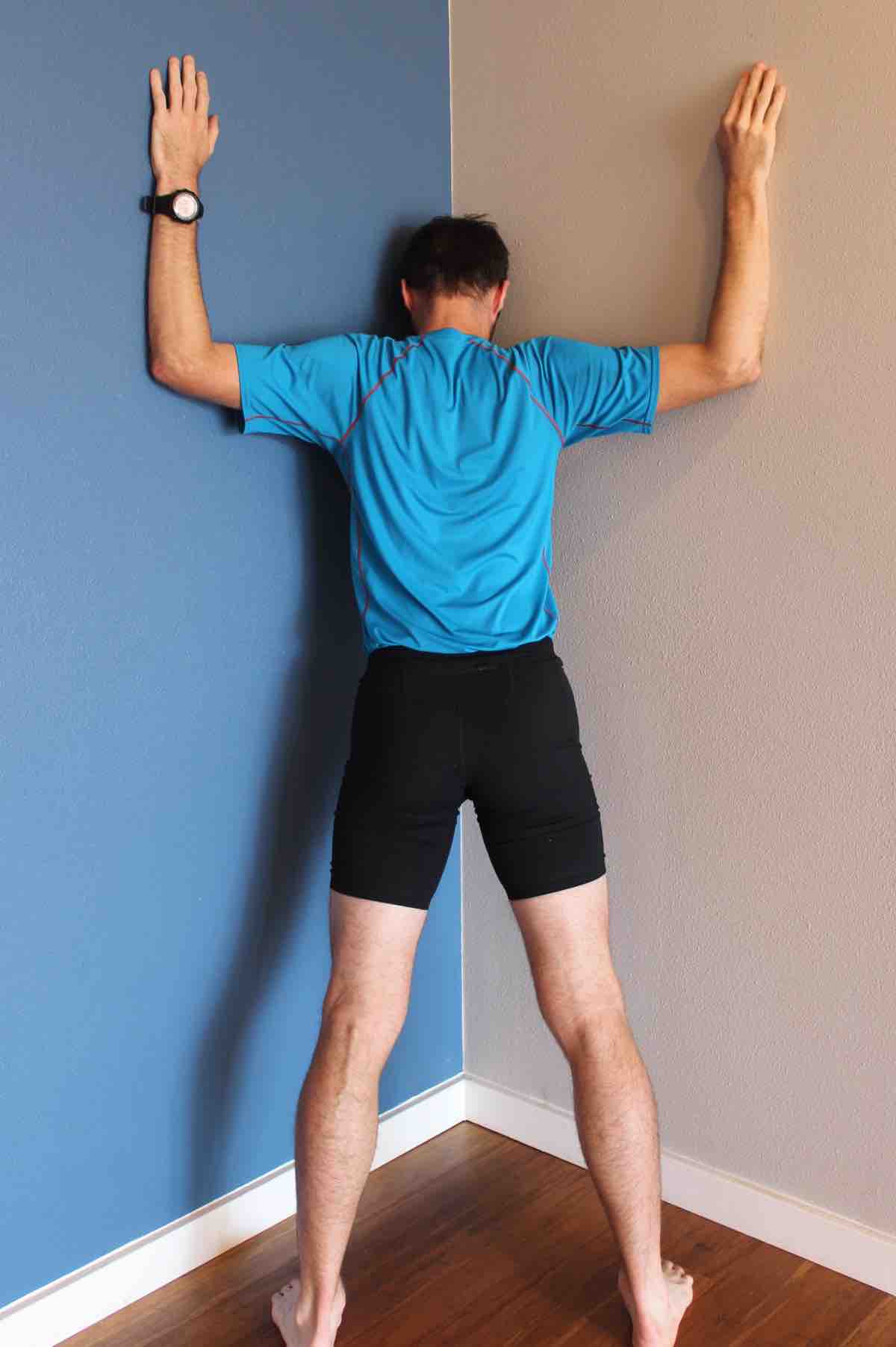

Chest-Opener Stretch

This exercise specifically targets the anterior chest. With a sustained rounded trunk, the muscles of the chest can become stiff, restricting the ability of the shoulder blades to extend.

To perform: Find either a wall, a corner, or simply a door frame. Position the elbow in the same overhead bent, cactus-pose-like position on the surface. Then, lean forward. If doing both arms at once, allow the trunk to relax forward. If performing on a single side, lean, then turn away.

Breathe deeply and hold this stretch for 10 to 60 seconds (depending on what feels best for you). This stretch can initially be performed multiple times a day to improve mobility, then occasionally before or after running.

Trunk alignment and posture is so much more than appearance, or prevention of neck or backache. Trunk mobility and position plays an enormous role in nearly every aspect of running. Keep tabs on yours, and keep it moving. It may, indeed, be your running fountain of youth.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Did you pass Joe Uhan’s test for trunk-extension mobility?

- If not, where were your deficits?