[Author’s Note: This is Part 4 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 3 on foot and ankle mobility, Part 5 on trunk extension, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

[Author’s Note: This is Part 4 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 3 on foot and ankle mobility, Part 5 on trunk extension, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

As we move along in the performance-mobility series, we turn to the lynchpin joint of the running system, the knee. The knee is the go-between for us and the ground. It is the highly mobile, multi-functional joint that allows a long, strong leg to instantly become short and flexible, making fast and agile running possible.

Thus, its ability to be both stable and mobile is what makes it so vitally important, yet so prone to dysfunction and injury. We will look at functional mobility of the knee joint, what it can tell us about our running, and how to optimize it.

Magda Boulet demonstrating healthy knee mechanics while descending Ben Lomond in New Zealand. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

The Knee Joint and Neutral Alignment

A year ago, I outlined the Ice Skater exercise: a single-leg stability strategy that is crucial for efficient running mechanics. Among the vitally important elements of this strategy is the ability to keep the knee neutrally aligned between the hip and foot.

This alignment has the knee in an outward bias over the second or third toe. And while an active, strong foot is foundational to this position, rotational hip strength plays the major role in maintaining knee alignment.

During trail running, this ‘knee-out’ alignment is constantly challenged by terrain and elevation. Both rugged footing and ups and downs demand greater hip strength to maintain neutral knee alignment, as does the distance and duration of ultra distances. The most common compensation or alignment deficit is knee valgus. This is a ‘buckling-in’ effect, where the hip is allowed to internally rotate and/or adduct. This creates an over-stretch effect on the medial side of the knee and a compressive effect on the outside–both of which may be painful.

If neutral, efficient knee alignment is lost, inefficiencies and compensations can propagate throughout the system, causing stiffness and range-of-motion loss at, above, and below the knee. In fact, a loss of knee alignment–usually when the knee buckles in–can cause range-of-motion loss and pain in the feet and ankles, hips, and spine. Thus, achieving and maintaining normal motion and strength at the knee may be the most important factor in whole-body efficiency and injury prevention.

Checking In: Motion Assessment at the Knee and What it Tells Us

Knee stiffness can be both a cause and effect of a running-stride inefficiency problem. A simple knee-flexion and extension motion assessment can tell us two things:

- Alignment: How well are the thigh and shin bones neutrally stacked upon one another? Any buckling-in habit can impair the knee’s ability to flex and extend through its full range.

- Impact stress: Excessive impact stress may result in both joint range-of-motion loss and/or excessive quadriceps stiffness and soreness.

When a knee buckles in, it can then create strain:

- On the same side at, above, or below the knees

- On the opposite side as push-off power is lost in the buckling-in side, causing increased landing stress on the other side

Thus, stiffness in knee and quad muscle mobility–especially if that impairment is asymmetrical, with one side stiffer than the other–can provide runners with good insight about running efficiency and possibly help identify a stride imbalance. This simple self-assessment stretch is described below.

The Knee Metric

This metric is simple, but informative:

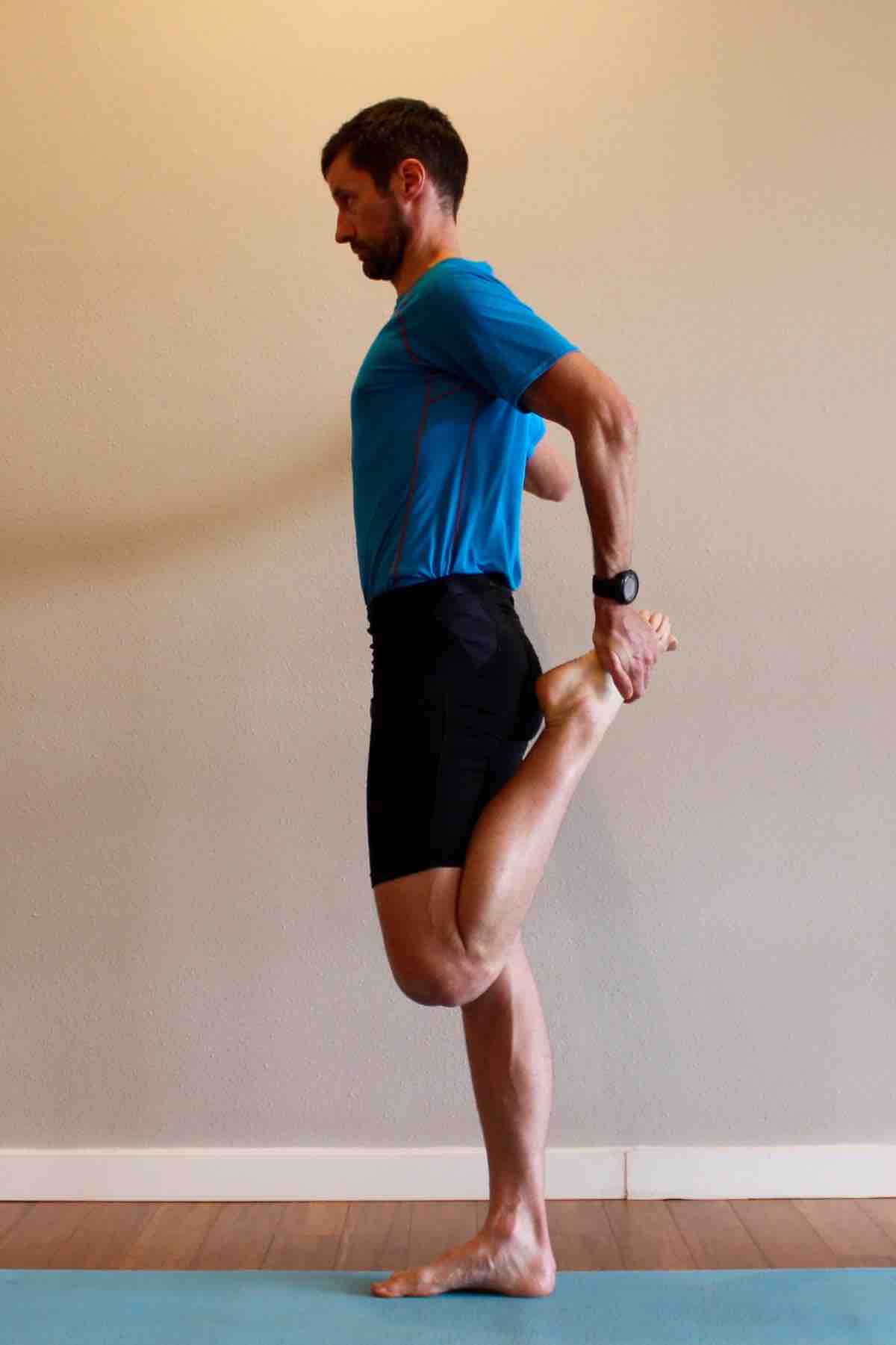

Details: In standing, begin by firming your abdomen. Maintaining low-back neutral (and avoiding excessive arching) is a key set-up to enhance the self-assessment. Grab your heel or curl your heel toward your buttocks, aiming to approximate your heel to your backside.

Goals:

- Heel should touch (or come close to) your buttocks

- Equal, symmetrical motion (left versus right)

Common Deficits:

- Overall range-of-motion deficit: Failure to be able to fully flex knee to butt. This could be due to joint (femur-on-tibia) motion, or due to tightness in the quadriceps muscles

- Asymmetry: Having a significant difference in range of motion and or perceived stretch between the two legs

Implications:

A deficit in mobility can tell you one of two things. First, a flat-out inability or asymmetry of flexion may mean your knee has an alignment deficit, possibly due to buckling in. Or, conversely, it may also mean that that knee (and, usually, the entire leg) is absorbing excess force. This is especially true if you notice increased quad tightness as well as generalized tightness or symptoms elsewhere in that leg–all indicators of excessive landing stress.

Restorative Exercises for Knee-Flexion Mobility

The Swivel Stretch

I actually devised this stretch a few years ago during a Western States Training Camp, a week-long training block that included multiple runs between 25 and 50 miles on the Western States course. I began to experience acute knee pain during the first run, a 42-mile run from Robie Point to the river and back. Knowing the prevalence of knee buckling in on such terrain, I simply aimed to do the opposite, to promote outward rotation with combined extension. My knee pain abolished immediately, and I had few issues with it for the remainder of the week.

To perform: Stand with feet shoulder width apart. Bend both knees about an inch. While maintaining a flat (but engaged) foot, outwardly rotate the knees, using your hip muscles. Maintain that outward pressure, then slowly squeeze your knees straight. Go slowly and be careful, as this could be painful or stiff. Then relax. Repeat up to five to 10 times.

This stretch addresses quadricep and hip-flexor muscle tightness in the running pattern.

To perform: Lie supine with legs extended. To stretch the right leg, half roll onto the left hip, and carefully flex your right foot under your butt (or as close to it as you can). Be sure the heel is centered under the right pelvis (not bent out to the side, which may exacerbate a sensitive knee). Ground the foot beneath the pelvis and the ground. Then, while maintaining the right foot on the ground, roll onto your left side. Once there, use your right hand to boost your left knee to your chest. This accentuates the stretch, protects the back, and mimics the running position. Hold this position for 10 to 60 seconds. This is a prolonged stretch for stiff muscles. Alternate sides, or spend additional time on the stiffer side.

The knee truly is the cornerstone of stride efficiency. Assessing and maintaining joint efficiency and motion is one of your best tools for pain-free and fast running!

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Do you pass Joe Uhan’s knee-mobility test? If not, what is your deficit? And is your deficit equal between both legs or prevalent in one more than the other?

- Do you have knee pain during trail running, either on rugged ground or when running uphill or downhill? Do you ever notice your knee buckling inward when trail running?