[Author’s Note: This is Part 3 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 4 on knee mobility, Part 5 on trunk extension, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

[Author’s Note: This is Part 3 in a six-part series on functional mobility self-assessment and restoration for runners. See Part 1 on hip mobility, Part 2 on trunk rotational mobility, Part 4 on knee mobility, Part 5 on trunk extension, and Part 6 on hip abduction and rotation mobility.]

At the beginning of this series, I introduced the concept of performance mobility. To reiterate, there are certain fundamental motions required for healthy, efficient running related to the hips, trunk (spine and chest), knees, and ankles. The purpose and utility of performance mobility is to provide runners a way to self-assess their motion and, if need be, improve and restore it. Through this self-assessment, runners can monitor and manage their own mobility, stretch only when (and what is) needed, and stay ahead of aches, pains, and injury.

After covering the hips and low back, it’s time to turn to where the rubber meets the road: the feet.

Ruth Croft during the 2016 The North Face Endurance Challenge 50 Mile Championships demonstrating healthy foot and ankle mechanics. Photo: Kirsten Kortebein

Elite Feet and the Demands of Mountain, Trail, and Ultrarunning

Two years ago I introduced a concept called ‘Elite Feet,’ which outlines the vital role that a neutral and powerful foot loading and push-off plays in efficient and powerful running. Boiled down to a single sentence: the whole foot must contact the ground, then, using primarily the medial arch, actively push off behind.

This concept is relatively simple on the consistently flat surfaces of road and track running. Trails? Mountains? Mud? An entirely different story. Terrain, elevation, and surface integrity drastically impact how we use our feet and foot mobility.

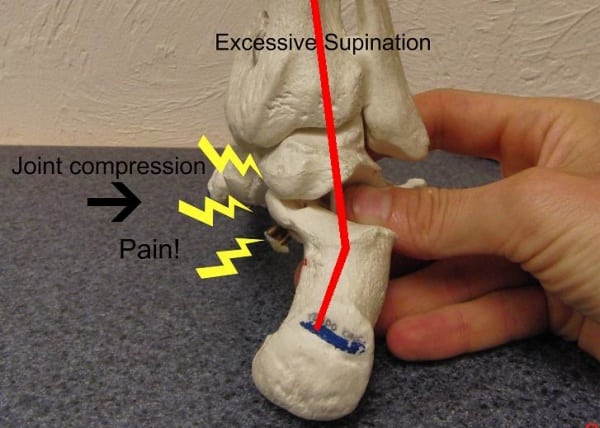

For heavy vertical and uneven surfaces, achieving neutral-footed ground contact can be a tall order. Steep and slanted rocks, roots, and debris often makes a neutral strike nearly impossible. On top of that, in order to enhance stability–and avoid a face plant–the body often creates compensatory stability by landing with extra supination. A hyper-lateral foot strike keeps the knee tracking in line with the hip at the expense of stressful foot and ankle loading.

Prolonged, steep descents and rugged terrain can thus pack a heavy one-two punch on the feet and ankles, potentially creating major range-of-motion impairments via super-stiff ankles.

In addition to steep and rocky terrain, untrustworthy surfaces–leaves, sand, mud, snow, and ice–also impair a strong, athletic foot push-off. Every trail runner out there has at one point had to revert to the ‘duck-waddle shuffle,’ a compensatory running style that avoids assertive foot strike and push-off to negotiate slick terrain. Although beneficial in the short-term, if this strategy is maintained, before long, a relaxed, athletic foot push-off is lost.

The author demonstrating the ‘duck-waddle shuffle’ at a very muddy 2015 Bandera 100k. Photo: Meredith Stevens

Stiff Ankle, Stiff Everything: Consequences of Lost Ankle Mobility

A whole-foot landing and active foot-and-ankle extension is the foundation of a strong overall leg push-off. Strong feet make strong hips. Conversely, a weak foot–due to stiffness or poor footing–impairs the entire system. Consequences of impaired foot push-off include:

- Foot, ankle, and calf pain

- Knee pain and stiffness (due to increased knee-flexion loading)

- Hip pain and stiffness (due to decreased hip extension)

- Low-back pain

While bilateral foot stiffness is problematic, any one-sided foot and ankle push-off impairment can have serious consequences to the system, creating a stride imbalance that can cause any number of injuries, ranging from foot to back pain–usually on the opposite side of the stiff foot and ankle!

The Foot- and Ankle-Extension Metric

While most runners are familiar with and employ ankle dorsiflexion (flexing) mobility, this metric assesses foot and ankle plantar flexion (extension):

Details: Begin by kneeling on the floor. (If you have sensitive or stiff knees, be very careful assuming this position. Go slowly and gently!) Slowly sit back on your heels. To further sensitize the test, try:

- Putting heels together (internally rotating the foot and lower leg)

- Wearing running shoes

Goals:

- Foot and ankle should be able to lie (mostly) flat on the ground

- Equal, symmetrical motion (left versus right)

Common Deficits:

- Overall range-of-motion deficit: failure to achieve full plantar flexion (foot, front of ankle, and shin all touching the floor).

Implications:

Stiff ankle plantar flexion is a key marker in how well one uses his or her foot in push-off. Stiff motion here means a deficiency in push-off, and is especially problematic if stiffness is one-sided. This is a red flag for a potential stride imbalance and future aches, pains, and injury.

Restorative Exercises for Ankle Plantar Flexion

Kneeling Sit-On-Heels

In this case, the restorative stretch is the same as the test: sitting on the heels.

To perform: kneel on the floor, putting feet and heels together. Slowly sit back onto the heels. Options include either holding this position for a prolonged stretch of 20 to 60 seconds, or oscillating the stretch by sitting down, then raising up off the heels.

Additionally:

- For moderate stiffness, simply sitting on the heels is sufficient.

- For severe stiffness, consider putting a small pillow or folded towel beneath the lower shins.

- For more subtle stiffness and to increase the stretch, wear shoes.

Kneeling Heel Pushes

This stretch more directly targets the posterior ankle joint by putting direct pressure on the talus, the ‘go-between’ bone of the ankle joint.

To perform: with shoes off, turn to one heel, put hand between ankle bone and heel, and push downward, toward the floor and the toes. Perform 10 to 20 consecutive on-and-off oscillations. If it is not too tender (but stiff), this push can become more aggressive.

Even in the absence of a major deficit, these exercises are excellent restorative stretches that help maintain foot and ankle flexibility. Best of all, improved plantarflexion mobility will enhance dorsiflexion motion as well!

Keeping the ankles supple, active, and strong is the subtle-but-crucial aspect of healthy and strong running. Check in with yours now and especially as your running volume and vertical increases!

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Do you pass Joe Uhan’s foot and ankle mobility test? If not, is there asymmetry between your left and right sides or do you have an overall loss of your range of motion?

- We asked the same question in the first two articles of this series, and we’ll try it again here. What kind of flexibility training or stretching do you engage in, if any? Do you find that it helps you in specific ways? If so, can you describe them?