Runners often believe that when they or their medical team discovers a strength imbalance, it is due to weakness. Meaning, there is a deficit within the muscle that requires increased strength. And that weakness is due to deficits within the muscle, necessitating growth of muscle fiber size (hypertrophy) or the overall number of muscle fibers (hyperplasia).

Runners often believe that when they or their medical team discovers a strength imbalance, it is due to weakness. Meaning, there is a deficit within the muscle that requires increased strength. And that weakness is due to deficits within the muscle, necessitating growth of muscle fiber size (hypertrophy) or the overall number of muscle fibers (hyperplasia).

This is a particularly curious theory for healthy runners, especially if they were previously high-functioning, and they didn’t incur a severe injury directly to the muscle in question which would cause an acute fiber integrity or quantity deficit.

Rather, the most common onset of weakness for runners is:

- Acute — Occurs suddenly, though without direct injury

- Insidious — Occurs without any direct mechanism or change in training

- Unilateral — Affects only one side of the body

Muscles do not radically lose or gain muscle fiber size or quantity, and a runner wouldn’t lose unilateral muscle strength simply because they are weak. Something else is going on. And that something is called neuromuscular inhibition.

Neuromuscular inhibition is a short-circuiting of the nerve-muscle connection, affecting either the motor nerve unit, the muscle, or both. And there are a variety of reasons that such inhibition occurs.

But before diving into the types of inhibition, it’s crucial to point out why the recognition of inhibition is so important.

Ashley Nordell finishing strong at the 2017 Lake Sonoma 50 Mile. Step 1 to getting back to strong, healthy running might be recognizing muscle inhibition. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Is it the Fridge or the Fuse: The Difference Between Weakness and Inhibition

You walk into the kitchen, looking for a cool beverage or snack. You open the door, and tragedy strikes. The light fails to turn on, and the contents seem lukewarm. What to do?

Many might instinctively believe the fridge is broken. If we stopped there, we might be inclined to immediately go shopping for a new fridge, install it, and restock the spoiled food.

Problem solved, right? But, since most of us are a bit savvier with fridges — or, perhaps, less quick to part with hundreds of dollars — we consider another possibility: a blown fuse.

The blown fuse is a safety measure in our home’s electrical circuitry that prevents system overload. When danger is perceived, the fuse blows, and all appliances loading that electrical line are deactivated.

Failure to acknowledge a blown fuse, in this case, would be a tremendous waste of money, time, and effort. For us to purchase a brand-new fridge, then restock it completely with fresh food would be met with the same frustration at the next snack time. If the electrical line is experiencing danger, we’ll again have lukewarm food.

Yet, so it seems, we as runners tend to engage in such folly when it comes to strengthening weakness. A better approach is to recognize, restore, and prevent inhibition, which we’ll talk about in the rest of this article.

Three Types of Neuromuscular Inhibition

There are three main types of neuromuscular inhibition commonly seen with healthy athletes:

- Pain inhibition

- Proprioceptive inhibition

- Disuse inhibition

Let’s dive in deep with each of these forms now.

Pain Inhibition

Acute pain, with or without the presence of inflammation, causes an automatic deactivation of muscle groups.

It is believed that pain inhibition is self-preserving: a nervous system protects an acutely injured knee, for example, by shutting off the quadriceps. Without such pain inhibition, we might carry on running through the jungle and continue to damage the injured joint. This is widely seen in knee surgeries, where there is patently no quadriceps muscle damage, yet the quad muscles becomes instantly weak by inhibition.

Acute knee pain can trigger a deactivation of the quadriceps muscles as a means of self-preservation. Photo: Shutterstock

But like a fridge with only a briefly blown fuse, an inhibited muscle will not atrophy unless that inhibition (and the pain driving it) is sustained and prolonged. Failure to restore that muscle activation after acute pain has subsided may actually lead to chronic pain.

In the case of a knee that has undergone surgery, the role of immediate neuromuscular rehabilitative exercise, therefore, is less about increasing strength as it is turning the power back onto a surgically repaired knee as soon as possible.

The other area of the body this is commonly seen is in the lumbar spine, with decreased low back core muscle (multifidus) activation with low back pain. Over time, this chronically inhibited muscle group will atrophy.

Proprioceptive Inhibition

This is a situation where surrounding muscle groups become deactivated if a joint or joint system either loses motion, becomes misaligned, or otherwise loses its natural efficiency.

Neutral posture results in automatic core muscle activation of both anterior (abdominal), posterior (multifidi), and lateral (oblique) core muscles. Conversely, like magnets pointed just offline, axial misalignment can cause immediate inhibition of those core muscles.

It may seem preposterous to the uninformed, or magical to those seeing it or feeling it firsthand, but immediate strength differences occur in different alignments. This is something I frequently demonstrate both in the clinic and in coaching and sports-medicine seminars that I lead. More clinically, it is possible to cause, then restore, measurable arm and leg weakness with different spinal positions and motions.

Proprioceptive inhibition occurs, therefore, when proprioceptive elements around those joints sense that adjacent bones are neither optimally aligned nor stabilized to handle load. Again, the theory here is that the nervous system — wary of potential strain on the spinal cord and nerve roots — inhibits limb musculature to prevent overload and potential harm to those vulnerable nerves.

As such, common complaints such as “weak glutes” often have as much to do with range of motion and alignment deficits in the spine, pelvis, and hip joints than it has anything to do with the size of the muscles.

Disuse Inhibition

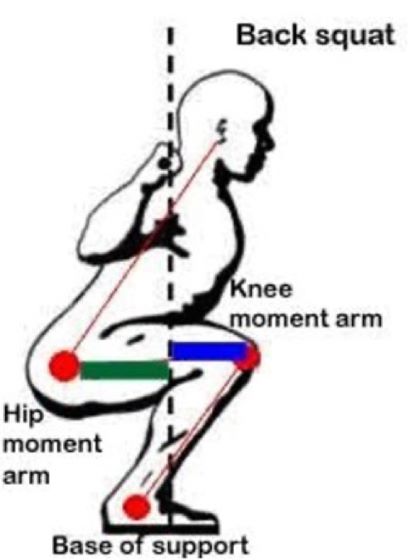

A hip-hinge squat, indicating the length of movement (or lever) arm. A longer arm equates to more force (via torque) that enters the joint. Image: Ptdirect.com/training-design/training-fundamentals/moment-arms-force-vectors-and-a-squat-analysis

Unlike the previous two, disuse inhibition is most locally influenced. Muscle groups will become inhibited if they fail to be loaded. To optimally use a muscle requires a load of force be placed upon it. Load can be placed in a muscle either through a stretch of the myofascial unit (the muscle, its tendon, and connected fascia), or through a torque, positioning a joint or muscle in line, but a distance away, from work.

The easiest conceptual example of both stretch- and torque-based activation is hip hinging. A hip-hinge posture places the hip complex behind our center of mass. Thus, when we strike the ground, the force travels up the leg and into the hip complex — which is hinged behind, with the glutes on stretch.

However, runners without any hip hinge at all put next to no force into the hip complex. A pelvis directly under the landing force produces no torque (as the lever arm is negligible), nor is there any pre-stretch to the glutes themselves.

Thus, running without hip hinge will make it neuromuscularly impossible to fire the glutes. They are disused. Then, as is the case with the other types, prolonged disuse inhibition will lead to atrophy.

Other More Sinister Causes of Neuromuscular Inhibition

The remaining causes of inhibition are also usually acute, but caused by more acute and severe pathology:

- Nerve damage — Trauma, spinal cord or nerve root compression (e.g., disc injury), or neoplasm (tumor)

- Stroke — ischemic or hemorrhagic nerve pathology

Fixing and Preventing Neuromuscular Inhibition

Following the blown fuse analogy, simply engaging in a strength program for the affected muscle hardly ever works in an inhibited state — unless the original source of the inhibition has been resolved. A new fridge with new food won’t cool on an inhibited outlet. Similarly, core musculature won’t fire around a misaligned spine, and a quadricep muscle will not get stronger amidst a painful, acutely swollen knee.

There are three keys to improving inhibition.

1. Resolve Pain

Avoid pain inhibition by eliminating the source of the pain. This may be easier said than done, but often in cases of acute trauma it requires adequate rest or, in severe cases, surgical repair.

In other cases, appropriate multi-dimensional regional treatment may be required. For example, mobilization of the lumbar, sacrum, and pelvic regions to relieve low back pain and restore multifidus activation.

2. Restore Full Tissue Motion

Stiff joints — including knees, hips, and the spine — inhibit both the mover and stabilizer muscles around them. Restoring full and balanced range of motion may require a variety of strategies, including stretching, joint mobilization, or manipulation. Once moving, the muscles responsible for protecting and moving that joint can be efficiently and sustainably reactivated using exercise.

3. Optimize Efficient Alignment and Motor Control

Once pain is resolved and motion restored, the key to sustained muscle activation is engaging the system — a given joint complex like the hip, or a multi-bone system like the spine — with optimal alignment. A stacked, balanced spine with a hip hinge creates both automatic core and glute engagement.

This is another example of the saying, “The best exercise is living well.” Align and move with efficiency, and muscles will automatically stay activated and get stronger.

Reinforce Strength by Reinforcing Efficiency

If we want to preserve and promote an intact and robust neuromuscular system, we need to keep that electrical system:

- Dry — free from wet inflammation

- Free from rust — free from “resistance” along the cable

- Aligned — wires properly connected

Once those objectives are met, then is the time to apply strength.

In fact, the best way to develop both more muscle fiber size and number, reinforce alignment and motor control efficiency, maintain optimal range of motion, and prevent pain is to not only run in the most efficient way, but to also apply non-running strength exercises in that efficient alignment and posture.

This may include running-specific strength exercises, such as the split squat, but may involve foundational, heavy-load strength exercises utilizing pristine spinal alignment and hip loading, such as the deadlift.

Joe Uhan demonstrates the proper “down” position of the split squat, the posture differentiating it from a regular squat. Photo: Joe Uhan

A Final Word: Facilitating a Sleepy Situation

Even after pain is resolved, motion restored, and efficiency is optimize, a muscle group might still be sluggish. This is when specific facilitating exercises are useful, namely for core musculature.

This is because, when core muscles are inhibited, the body resorts to using phasic or the mover muscles, to stabilize. In the spine, for example, the rectus abdominis (the six-pack muscle) may substitute for an inhibited transverse abdominis (a deep core muscle). Or in the hip, hamstrings and adductors may substitute in for inhibited gluteal muscles.

Facilitation exercises work using prolonged holds in functional movement patterns. Again, absent pain and with motion restored, these patterns are held for long enough for the short-acting phasic muscles to fatigue and for the brain to find and reactivate the core.

Here are examples of these types of facilitatory exercises:

- Diagonal chop exercise for the transverse abdominis

- Short and long exercise for the gluteus medius

Conclusion

Muscles seldom lose strength without good reason, and that reason is hardly ever an issue of fiber size or number. Rather, the nervous system inhibits muscles for various — and often good — reasons.

The key to optimal strength and our most optimal, pain-free performance, therefore, is to identify what factors cause inhibition, and apply effective strategies to restore and prevent it.

Call for Comments

- Have you experienced muscle inhibition for any of the reasons outlined above?

- What helped you to get firing on all cylinders again?!