Somebody once said, “the better you know something, the easier it is to describe.” The latter is certainly true with my ability to describe running efficiency. Six-plus years ago, my definition was a Twitter-worthy 55 characters. Today, it’s even trimmer: forward posture, rearward limbs. But those 32 characters still don’t quite do justice to a sport that, while utterly simple, seems utterly impossible to avoid injury.

Somebody once said, “the better you know something, the easier it is to describe.” The latter is certainly true with my ability to describe running efficiency. Six-plus years ago, my definition was a Twitter-worthy 55 characters. Today, it’s even trimmer: forward posture, rearward limbs. But those 32 characters still don’t quite do justice to a sport that, while utterly simple, seems utterly impossible to avoid injury.

To distill it even more, running is two concepts: posture and propulsion. Why is posture important? Ask the average person and they might say, “to prevent a sore neck or back.” What if I said that posture decides:

- If our core-stability system engaged;

- How we land on the ground, stay stable, and push off; and

- If we can get a full breath?

Posture goes beyond simple alignment. It affects the entirety of our running efficiency. Thus, it has to be addressed as the foundation and is deserving of a second take in this article.

What is Ideal Posture?

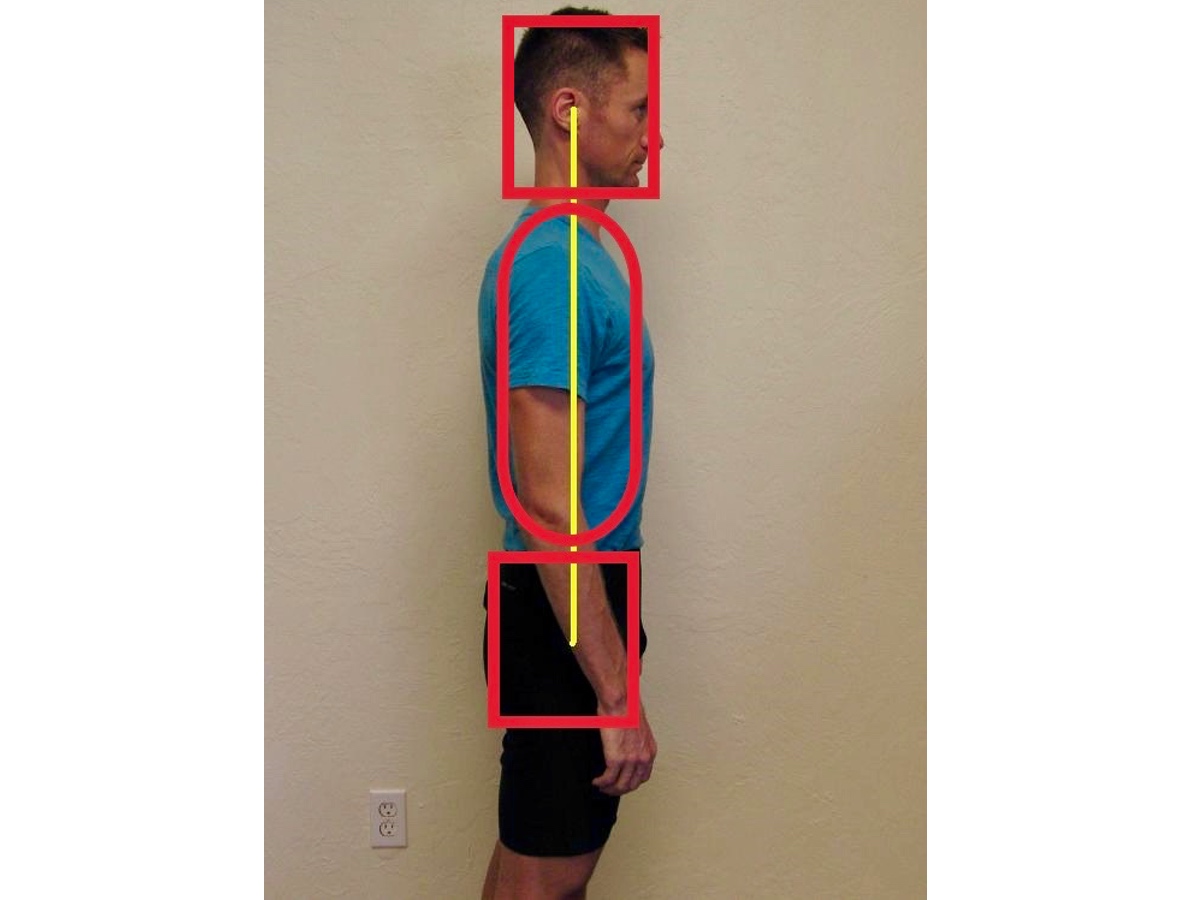

Simply put, ideal posture is a stacking of body systems in a straight line. Each body system is comprised of one or more bones and joints–lower leg, thigh, pelvis, trunk, neck, and head–independent of one another. Thus, ‘alignment’ is the idea that each system stacks on top of one another in a straight line. (In our original posture article, we discuss various running postures with inefficient alignment.)

[Author’s Note: This posture theory is based on the Saliba Postural Classification System. A special thanks to the Institute of Physical Art for the instruction on this classification system and corrective techniques. Reference: The reliability and validity of the Saliba Postural Classification System. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/10669817.2016.1138599 by CK Collins, V Saliba Johnson, EM Godwin, E Pappas (2016).]

However, alignment actually has two dimensions: position and angle.

Position

Position relates to whether or not each system–say, the ribcage–is stacked directly on top and/or below adjacent systems. For instance, does the ribcage stack on top of the pelvis, and does the neck stack on top of the ribcage?

Angle

Angle relates to the orientation of each system. Is each system angled in a neutral direction? Or is one system angled too far forward (anterior) or rearward (posterior)? Ideally, at each system, the forward or rearward angulation should be minimal. The notable exception occurs in the spine, which has two small extension curves–lumbar and cervical–that are counterbalanced by a flexion curve in the thoracic (ribcage/trunk) area. In the efficient state, these curvatures are rather minimal, but they can exaggerate when inefficient.

Posture Impairment at the Trunk and Pelvis: The Efficiency Killer

The most common and impactful postural deficits occur at the trunk and pelvis. These are common because, in the human body, there is a lot of leeway and freedom to how the trunk and pelvis move. But in prolonged locomotion, we desire a stacked, neutral system.

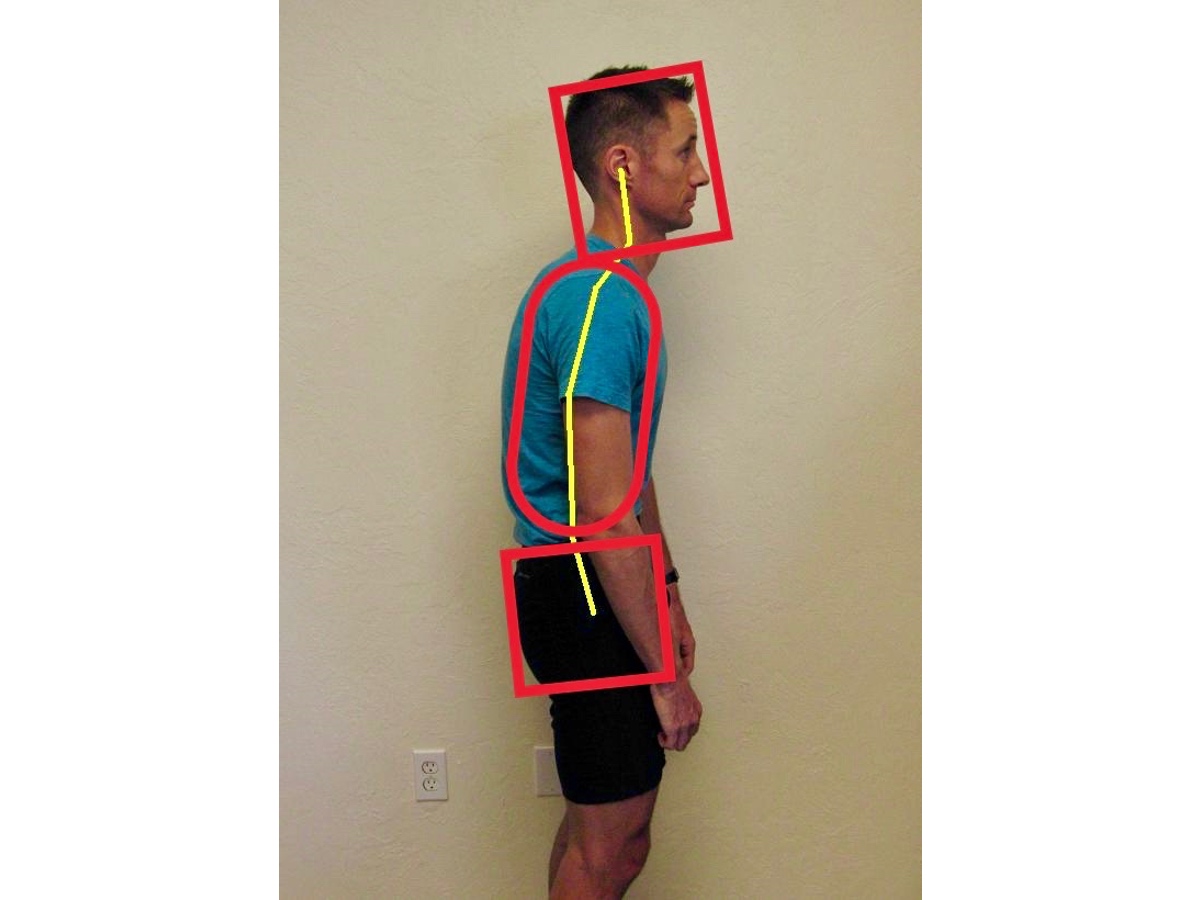

Trunk-On-Pelvis Position

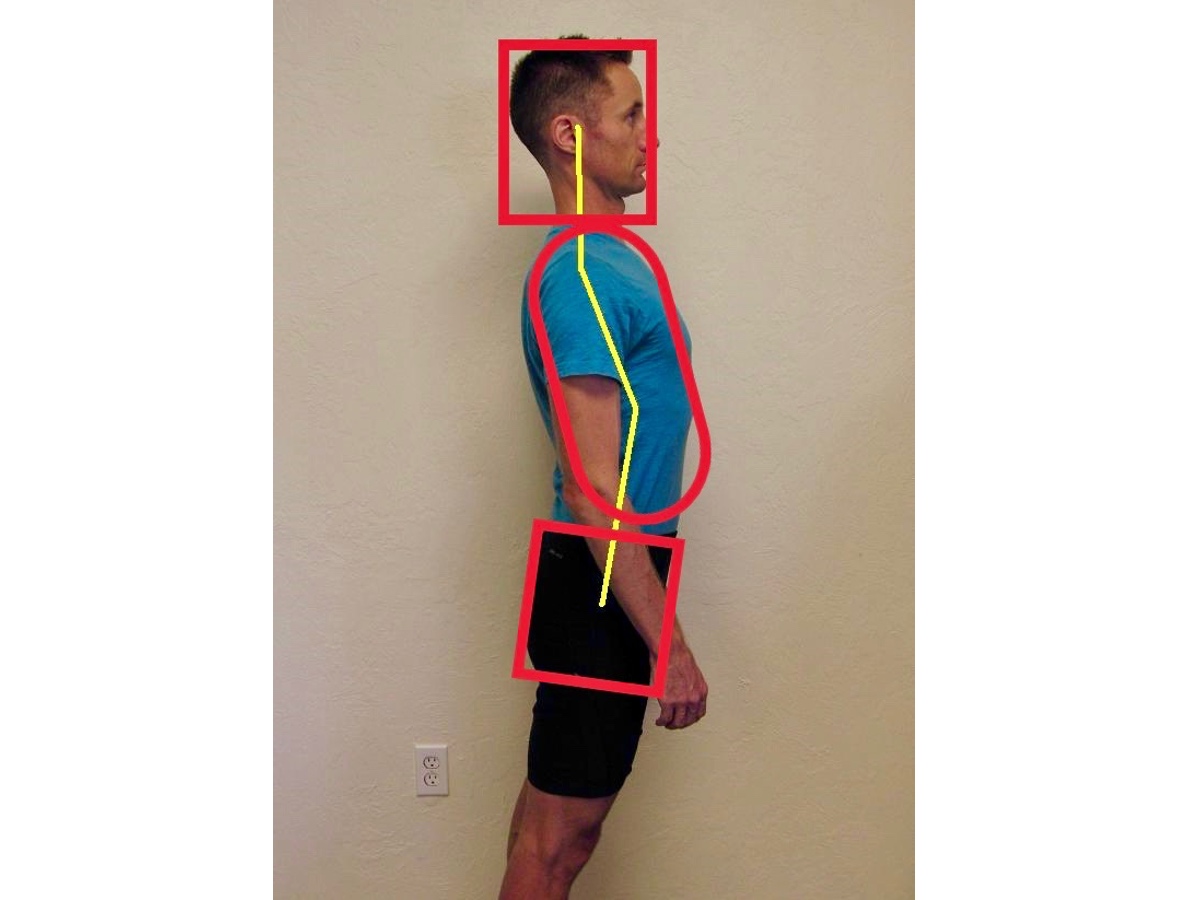

The first common postural deficit among runners is a stacking inefficiency of the trunk on the pelvis. This occurs when the trunk is either too far forward (anterior) or too far rearward (posterior):

In my clinical observation, the latter is far more common. This malalignment can happen from above–trunk on pelvis–or from below–the pelvis shifted too far in either direction atop the legs!

Ribcage Angle

Issues of angle are most evident in the ribcage. The ribcage is a bell-shaped structure, as it’s rounded near the top and has both a forward and rearward curvature. Like a church bell in a neutral state, that bell should ‘hang’ straight down, with equal curvature in front and back.

Too often, however, that bell ‘rings’ to one direction, angling (or leaning) forward or back. For a majority of runners, the trunk tends to be overly extended and angled backward, meaning that the bottom ‘rings’ forward:

An inefficient ribcage angle can have negative effects throughout our whole body.

Poor Posture Makes Running Slow and Painful

These positional or angle issues may seem subtle, but their effects on running efficiency are massive. In our first posture article, the thesis was that “poor posture will cause increased landing stress.” This is true, but it’s only a small part of the story. Indeed, a rearward orientation–in either position or angle–shifts the center of mass rearward, making it easier to over-stride. Over-striding creates excessive braking forces that must be absorbed by the body.

But inefficient posture also affects propulsion in major ways. First, inefficient stacking impairs the hips’ ability to push off. A forward pelvis (on a rearward trunk) prevents the hips from fully extending behind.

Second, inefficient posture dramatically impairs anterior core (abdominal) function. Automatic and efficient core activation requires that the spine and pelvis have both efficient stacking and angulation. If stacking is impaired–with the trunk shifted ‘off’ the pelvis–or if the trunk is excessively angled, the abs are in an overstretched position and can deactivate.

Impaired abdominal function is a big problem. Not only do the abs help maintain stability upon landing, but the abs are a powerful hip-flexion assist in the running stride. Our lower abs play a huge role in helping flex the leg upward and forward. Without the abs, the hip flexors will fatigue quickly and turn a strong stride into a shuffle, or turn an efficient landing into a lope-y over-stride.

Lastly, inefficient trunk and pelvis stacking and angulation can impair breathing! Poor ribcage angulation in particular impairs our ability to efficiently inflate and deflate the lungs, making our breath only a fraction of its potential.

Weak push-off, weak forward lift, and poor breath: all the physical training and mental toughness in the world cannot overcome these running-efficiency killers. Simply put, poor posture makes for slow and painful running!

Shore It Up: Find (And Maintain) Your Posture Neutral

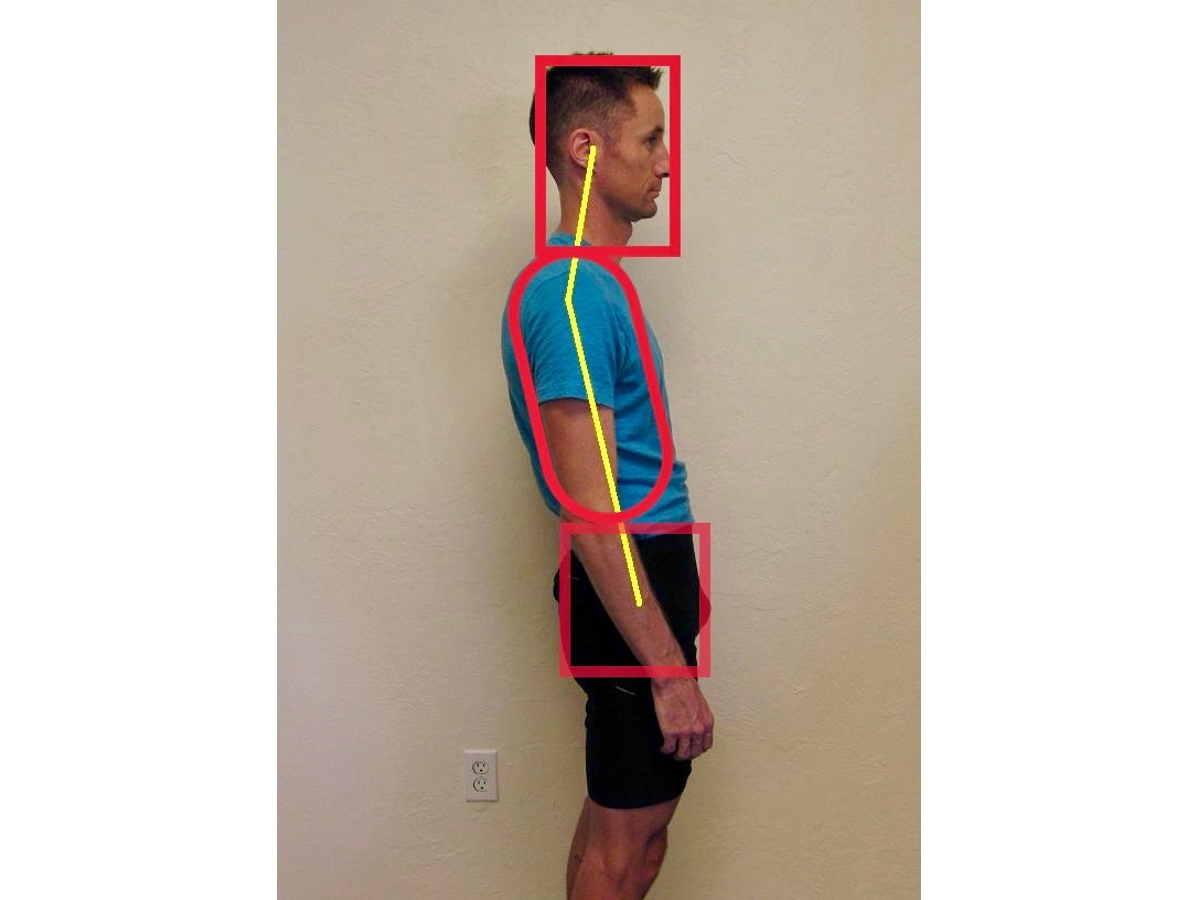

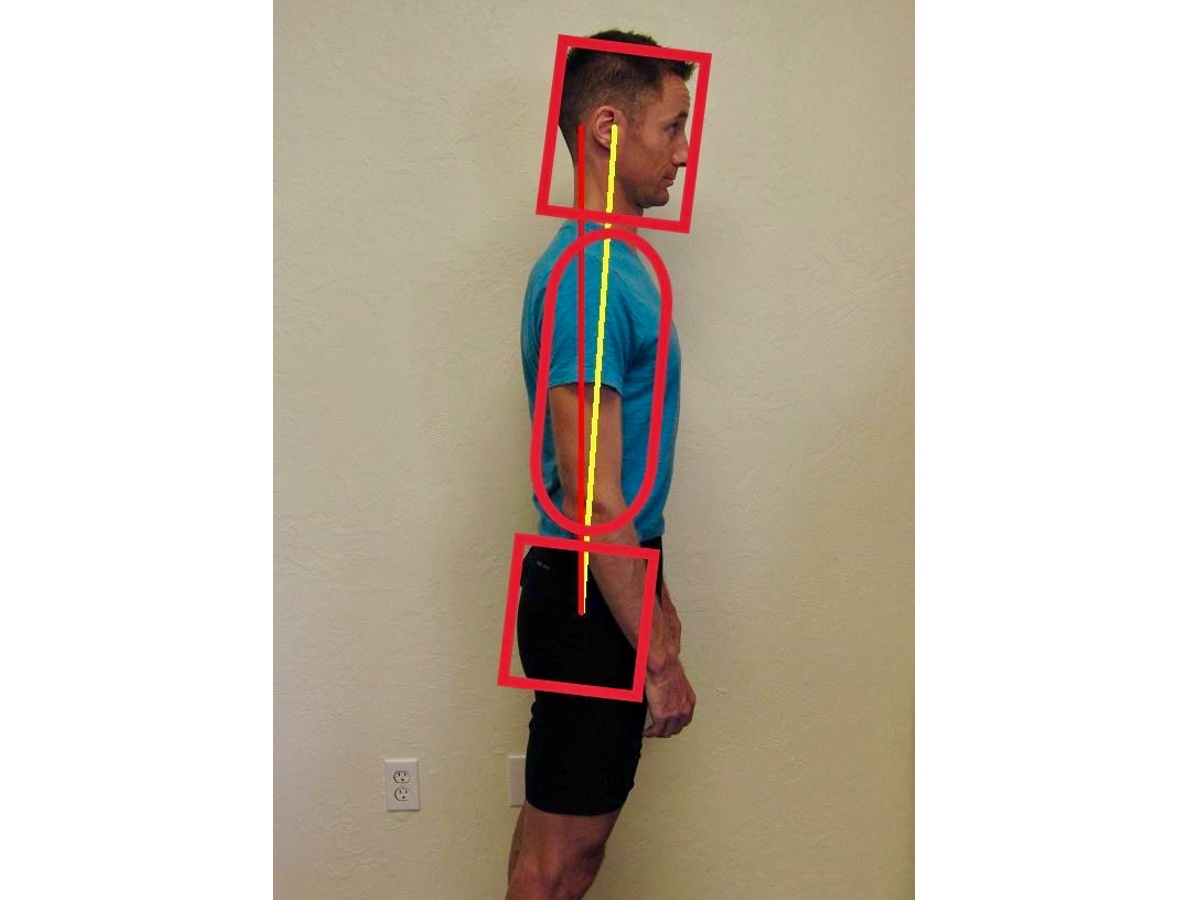

Finding neutral posture is easier that it sounds. All you need is a full-length mirror and your two hands. Here’s a how-to:

Feel It: First, place one hand at your ‘belt buckle’ and the other on your sternum (chest bone).

Stack It: Then, adjust your stacking alignment by moving your trunk and pelvis such that your hands stack vertically and your body systems below (lower and upper legs) are directly beneath the pelvis.

‘Neutral Bell:’ Adjust your trunk position so that the ribcage ‘bell’ is ‘hanging’ in neutral. For a posterior (back-leaning, extended) trunk, this involves substantial sternum relaxation downward toward the belly button. For an anterior (forward, flexed) trunk, it is the opposite.

Shoulder Adjust: If the trunk angle changed substantially, it will take with it the shoulders and neck. Place the shoulders neutrally atop the trunk.

Neck Adjust: Lastly, stack the head and neck (as best you can) atop the ribcage. This is usually a rearward and upward lengthening, as if the back of the head is pulled upward from a string.

This video explains the concepts of neutral posture and applies it to the running motion:

Because of long-present posture habits, this process can be simple to establish but difficult and awkward to maintain for more than a short time. This is often due to significant joint and soft-tissue restrictions, especially in the ribcage, shoulders, and neck. These deficits can greatly improve with upper-body mobility work. (This deficit was discussed in our article on trunk and shoulder mobility. We also discussed further treatment techniques using a foam roller in another article).

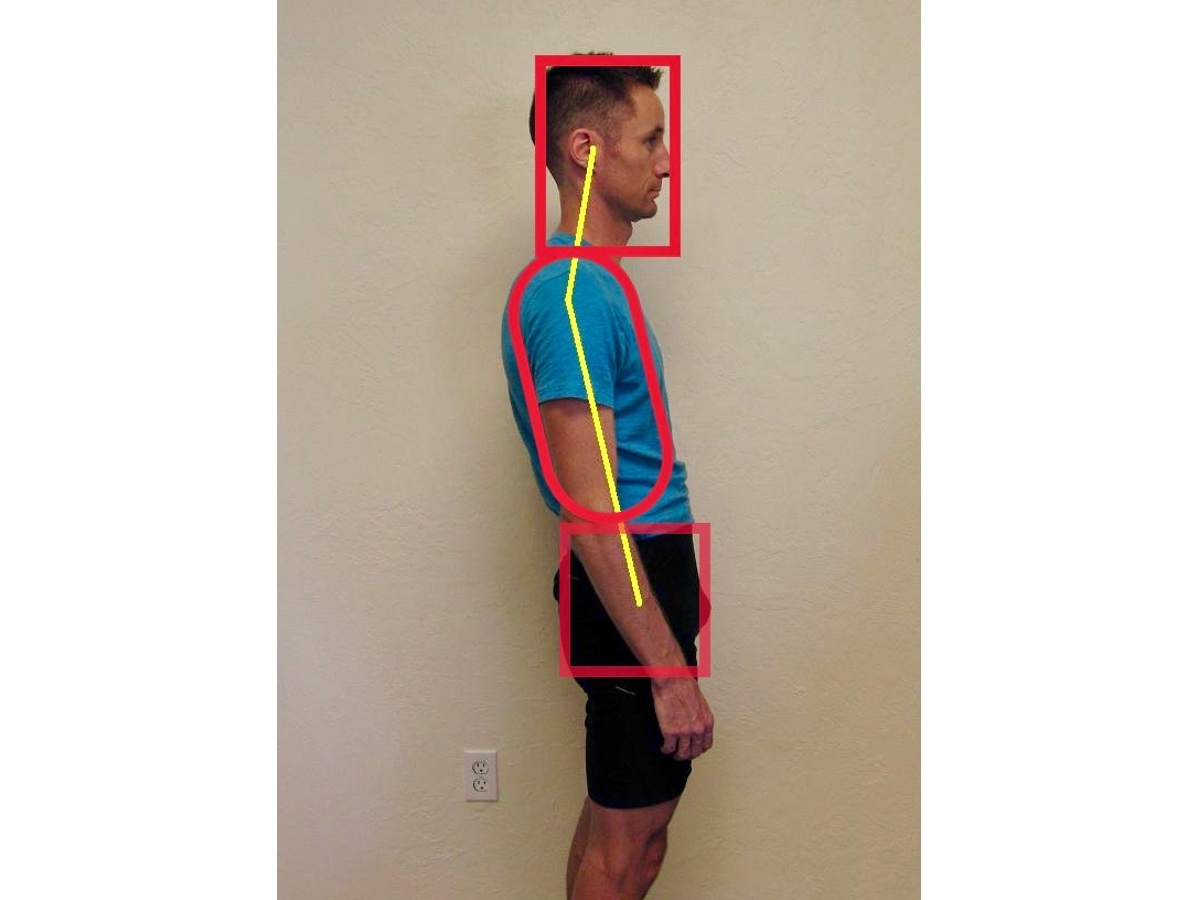

Once you can achieve neutral posture in standing, the key is to adopt it into your running. The main difference between static standing and running is the forward orientation:

In a forward orientation for running, the alignment remains in a straight line but there is a forward inclination at the angle and hip hinge, which naturally puts the rest of your body forward. For those of you who tend to overextend the trunk, you’ll be shocked at how much easier it is to get and stay forward-oriented in your stride!

Get Help

If you struggle with finding or maintaining a neutral posture, get some help. Another running friend is a good start, but if you’re simply too stiff to get where you need to be, a skilled physio can help you get there.

Then, know and remember the importance of applying your unique postural needs in and out of your running. For example, if you struggle with a rear-stacked and rear-angled trunk, maintaining your pelvis well behind your trunk and relaxing the sternum needs to be an ongoing focus while running.

Find your efficient place before running and then occasionally check in during the course of a run, either visually (checking your reflection in a window, for example) or by placing your hands on your chest and pelvis.

More importantly, we run how we live so keeping neutral posture while sitting, standing, working, and driving is even more important. Fixing your posture by day will make it easier to stay efficient on the run.

I’d love to hear your feedback on how a neutral posture changes your landing, push-off, breathing, and overall speed, endurance, and enjoyment while running! Good luck.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- After using this article to find a neutral posture, where does your current posture match and where does it deviate?

- In consciously taking a neutral posture into your running, do you notice any outright differences in how running feels?

- Since so many of our posture habits develop in our regular life, what thoughts do you have about ‘shoring up your posture’ at work, in the car, and elsewhere?