When you read popular literature about various topics in women’s running, it is disturbing how often the articles take an apologetic form. Periods, menopause, and pregnancy: poor women having to deal with such things while trying to be athletes. But what if it is not ‘poor women?’ What if we instead look at these parts of being female as not only incredible examples of human physiology, but maybe even opportunities to take athletic advantage of?

This article will specifically look at:

- Research on the difference between women and men in endurance running;

- How endurance-sports performance can vary according to the menstrual cycle as well as how you might be able use this to your advantage;

- Amenorrhea (losing your period) and its physiological consequences; and

- Menopause and thriving in endurance sports with age.

Endurance-Running Performance Differences Between the Sexes

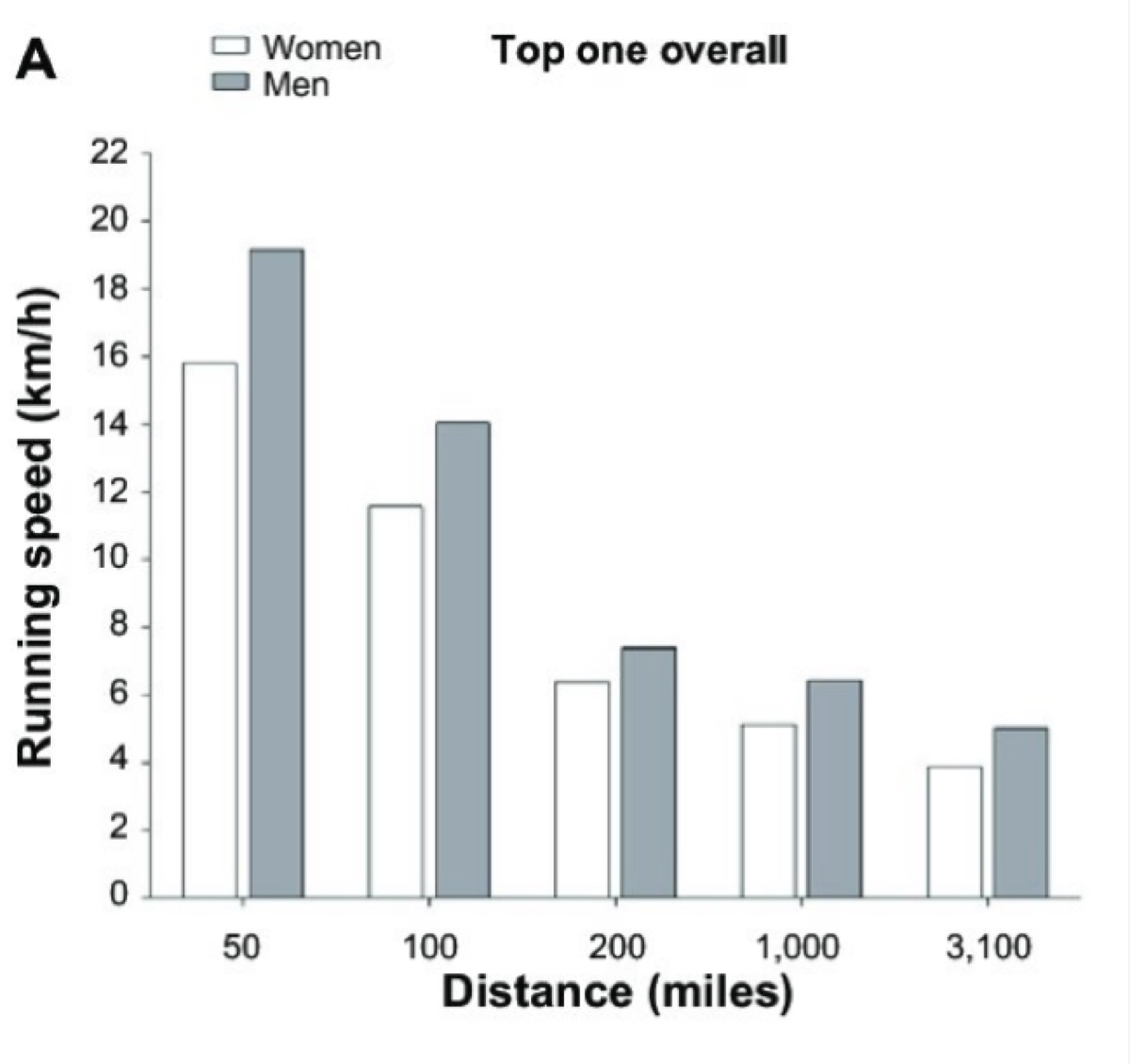

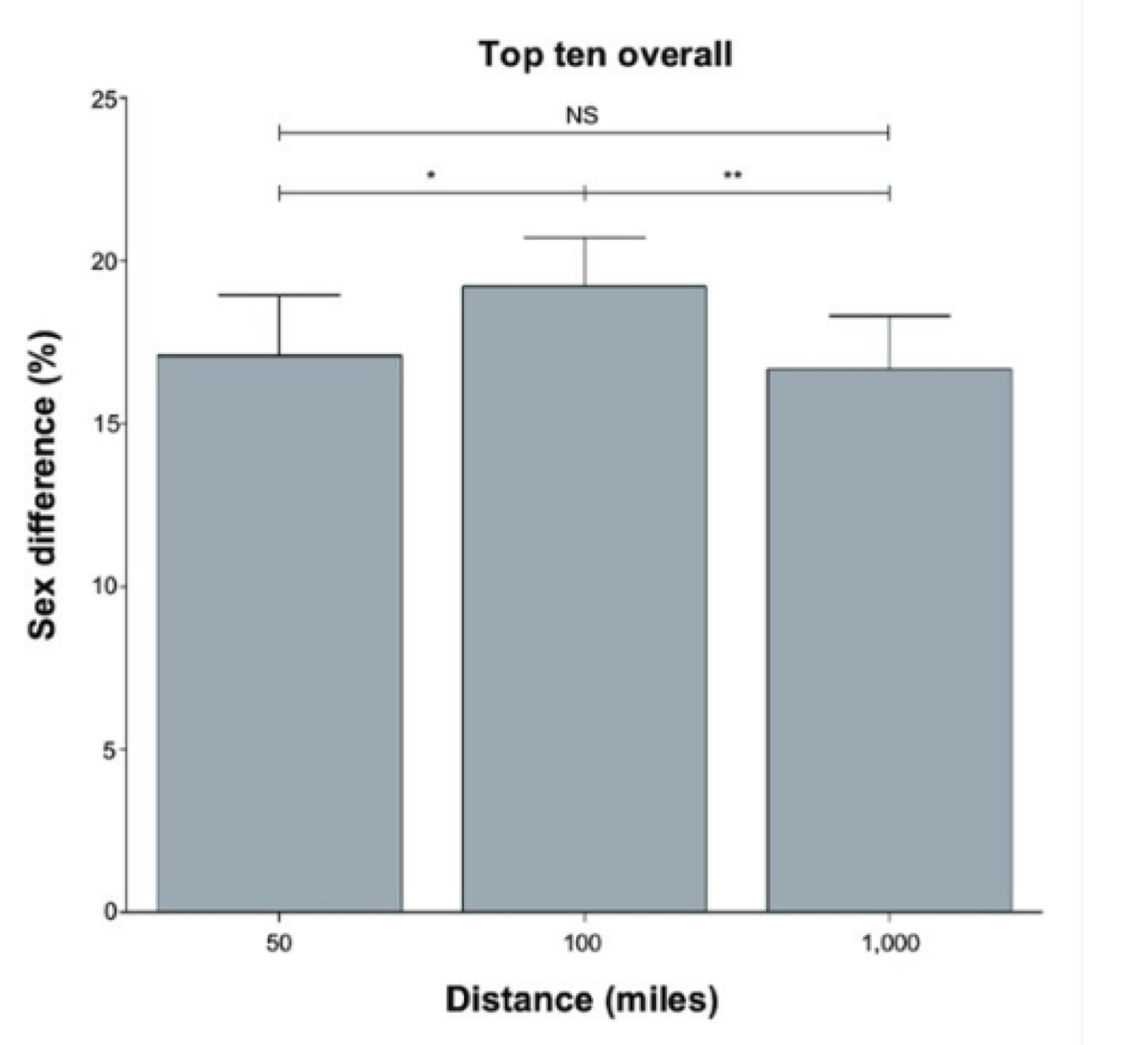

Despite popular belief, women do not on average perform better than men at ultramarathon distances. Not even close, really. The fastest men ever were faster than the fastest women ever in 50-mile (17.5% faster), 100-mile (17.4%), 200-mile (9.7%), 1,000-mile (20.2%), and 3,100-mile (18.6%) events. For the 10-fastest finishers ever, men were faster than women in 50-mile (17.1% ± 1.9%), 100-mile (19.2% ± 1.5%), and 1,000-mile (16.7% ± 1.6%) events (Zingg, 2015).

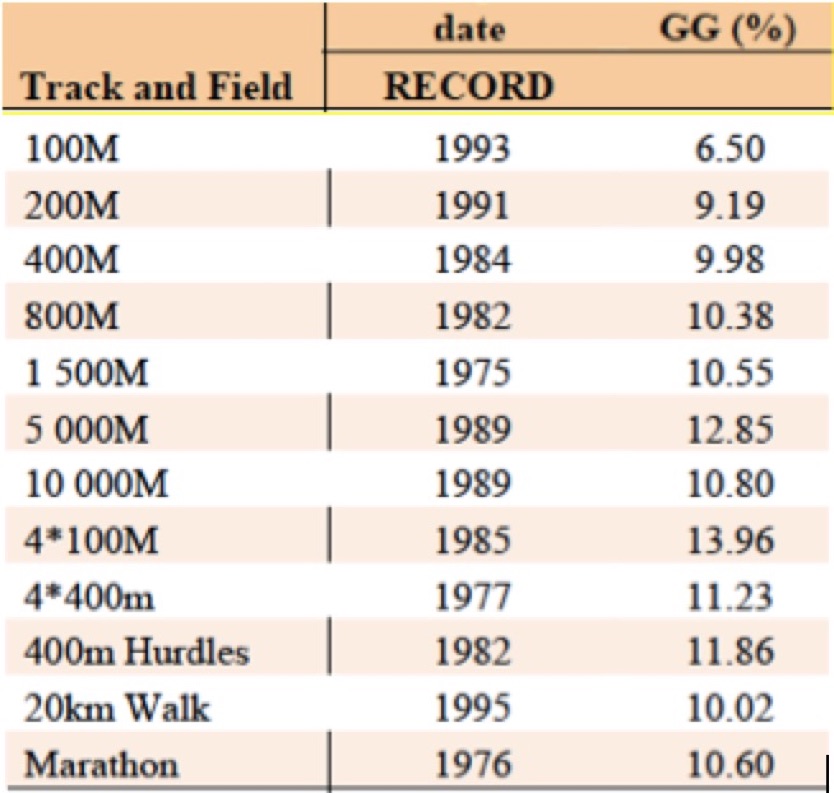

As you can see in Figures 1, 2, and 3, the difference between the top male and female performances in ultramarathons hovers between 15 and 20%, which is actually higher than the percent difference seen in conventional/shorter running distances and events.

Figure 1. This difference in running speed between the top men and women in ultramarathons (Zingg et al., 2015).

Figure 2. The average percent difference between top-10 male and female runners at the 50-, 100-, and 1,000-mile running distances (Zingg et al., 2015).

Figure 3. The world-record differences between the sexes in the marathon and shorter running distances. The differences are all

less than 14%, and even appear to decrease the shorter the distance. GG = Gender gap (Thibault, 2010).

That women might actually be relatively slower the longer the race is the opposite of what has been recently proposed in popular media (Brown, 2017). It currently appears that the difference between the best male and female performances increases percentage-wise the longer the race (to between 15 and 20%). However, we may see this gap narrow as female participation in ultramarathons continues to grow. [Edited, September 19: Subsequent to the above 2010 study, Camille Herron has in fact lowered the gender gap in the 50 mile to 14.3% below the men’s and in the 100 mile 9.7% below the men’s.]

When considering male versus female ultramarathon performance, it is important to remember that, though there are anecdotal reports of women winning overall in ultramarathons, there are similar anecdotes in 5k’s and marathons and that does not change the overall statistics that better represent human physiology. The author of this article, for example, has won a 6k and a 25 miler overall for men and women, but does not use this as evidence that women are better at running a 6k or 25-mile races than men. ;-) So even though Pamela Reed won the Badwater 135 and Courtney Dauwaulter won the Moab 200 Mile, this does not prove that women are better than men at longer distance races. Let us accurately call them phenomenal exceptions.

Aerobic Capacity and the Menstrual Cycle

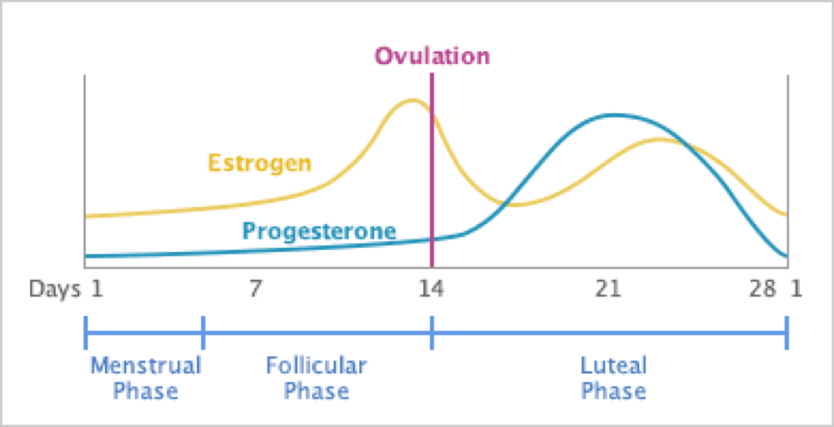

When reading the information in the next few sections of this article, it will be helpful to keep Figure 4 handy. My mnemonic for remembering how the menstrual cycle relates to training is:

- Follicular = Fast and first part of the cycle

- Luteal = Languid and last part of the cycle

However, this is an oversimplification because the ratio of the hormones estrogen and progesterone in our bodies is likely more important than the phase, so read on!

Figure 4. The levels of estrogen and progesterone across the typical 28-day female cycle with the period starting at day 1 (from https://www.drkarenfrackowiak.com/blog-drkaren-naturopathic-dartmouth/2017/2/28/pms-recognizing-the-signs-and-calming-the-craziness).

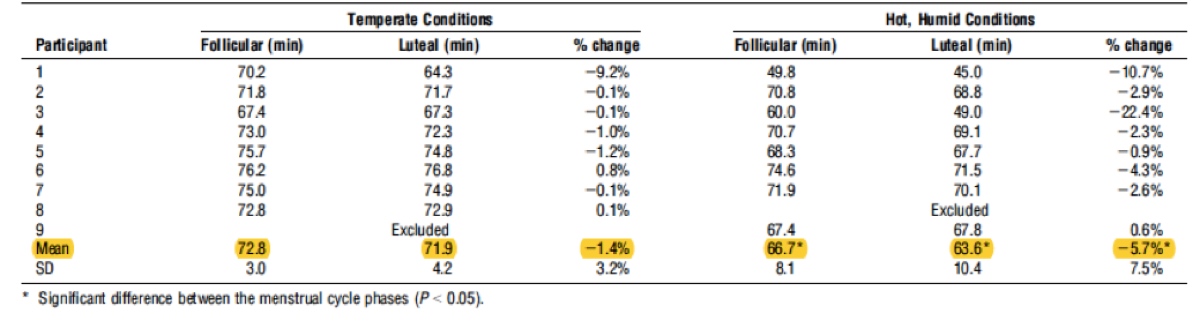

Though the realm of science involving athletics and the menstrual cycle has often involved small studies with inconsistent methodology, in general, in larger, well-designed studies, women are found to have improved aerobic capacity during the follicular phase (De Jonge, 2012; Sims, 2007; Julian, 2017; Lebrun, 1995). For example, one well-designed recent study in soccer players showed that nearly all of the study participants had increased time-trial running distance in the middle of the follicular phase compared with the mid-luteal phase (Julian, 2017). Another study in trained athletes found exercise capacity to be significantly higher in the follicular phase than the luteal; this study was conducted in a number of athletic disciplines including running, cycling, triathlon, squash, cross-country skiing, ultimate frisbee, and rowing (Lebrun, 1995). This increase in aerobic capacity in the follicular phase appears to be particularly pronounced in the heat (De Jonge, 2012; Sims, 2007). The improved aerobic performance during the follicular phase is felt to be mostly estrogen-mediated (Oosthuyse, 2010) and, rather than being an effect of the follicular phase itself, an effect of the estrogen-to-progesterone ratio (Janse de Jonge, 2003; Oosthuyse, 2010).

This is based on the basic research of estrogen’s effects on both aerobic capacity and muscle strength. For example, one animal study demonstrated the effects of estrogen particularly well, in which rats who had had their ovaries removed received low-dose estrogen supplementation and showed improvement in time to exhaustion in a prolonged sub-maximal treadmill run by 20% compared with placebo-injected rats (Kendrick, 1987). Estrogen has been found to have a number of beneficial metabolic effects when it comes to endurance including increasing storage of glycogen in muscles, free fatty acid availability, ability to burn fat, and oxidative capacity (muscles’ ability to use oxygen) in exercise (Oosthuyse, 2010, Charkoudian, 1997; Charkoudian, 1999; Hiroshoren, 2002; Houghton, 2002).

(Women may find they have increased caloric need during prolonged exercise when progesterone is high and have decreased need in general compared to men, not just because of less muscle mass, but perhaps due to the presence of estrogen, though I am unaware of a study that has shown this.)

But improved endurance performance in the follicular phase is likely also at least partially attributable to the lower levels of progesterone. The progesterone surge in the luteal phase raises body temperature between 0.3 to 0.5 degrees Celsius (Janse de Jonge, 2003). This increase in body temperature has been correlated with limiting prolonged exercise capabilities as well as increasing respiratory and heart rates (Janse de Jonge, 2003; Janse de Jonge 2012). (See more on the effects of progesterone in the luteal phase below.)

Finally, performances in all-out sprints have also been found to be best during menstruation (Brooks-Gunn, 1986; Gargiulo, 1991; Redman, 2004), where again, estrogen is the dominant hormone.

Figure 5. The increased mean time to exhaustion in the follicular phase, which did not reach significance in temperate conditions, but despite a small number of participants, did reach significance in hot and humid conditions. The mean is highlighted (Janse de Jonge, 2012).

Strength and the Menstrual Cycle

In terms of gaining muscle strength, overall, the existing data indicate a more anabolic state in the follicular phase and the peri-ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle, compared to a more catabolic state in the luteal phase (Sung, 2014). In other words, we tend to build up muscle when estrogen is dominant and break down muscle when progesterone rises. Estrogen has been found to build muscle strength via the improvement of the quality of muscle fibers rather than by increasing muscle bulk (Lowe, 2010).

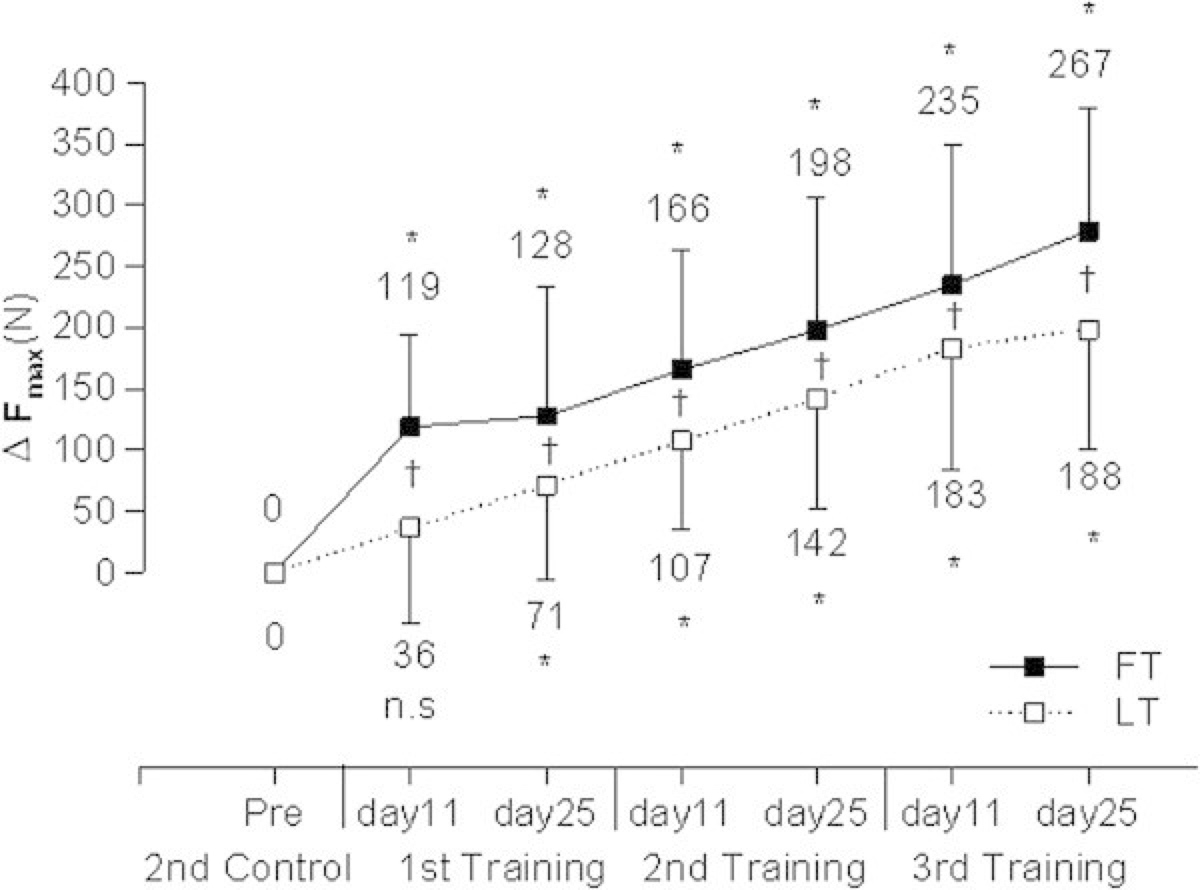

Estrogen may not be the only hormone that causes us to build muscle mass in that first part of the cycle; a 2014 study by Sung et al suggested that increasing levels of testosterone during the follicular phase may play a role in building muscle mass, though this theory has not been proven in women. This fascinating 2014 Sung study did find that a follicular-phase-based strength training program resulted in significantly increased maximum quadriceps (knee-extension) force compared with a program done in the luteal phase. Their results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Change in maximum force (F max, measured in Newtons (N)) of knee extension following follicular-based strength training (FT) versus luteal-based strength training (LT). The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd training cycles were based on each woman’s monthly cycle and were performed on day 11 and 25 of each woman’s cycle for three consecutive cycles. The Pre and 2nd control cycle values were both obtained from the study women two months and then one month prior to beginning the strength-training program (Sung, 2014).

Progesterone and the Luteal Phase: When Endurance May Decline

There are a number of reasons women may not feel well during aerobic exercise in the luteal phase of their cycle. As discussed above, as progesterone rises (after ovulation), you can expect your core temperature to rise 0.3 to 0.5 degrees Celsius and along with it, you will get hotter than normal before you begin to sweat (Janse de Jonge, 2003; Karp, 2012). Along with this, the rising progesterone in the luteal phase will cause increased breathing and heart rates and you may feel more easily winded as a result (Bayliss, 1987; Janse de Jonge, 2003).

As an aside, this is also what happens in the first trimester of pregnancy when progesterone rises quickly to very high levels and women often note they are easily winded, even very early on in pregnancy (Klarlund-Pedersen, 2012).

Along with this, another very interesting change in the luteal phase is that blood-plasma volume decreases by up to 8% (Oian, 1987; Stachenfled, 1999). But what goes down must go up and, as plasma volume rises again in the follicular phase, a woman can expect a corresponding increase in exercise capacity (Coyle, 1990). This is because increasing your plasma volume provides improves heat dissipation, decreases heart rate, and increases output from the heart (Convertino, 1991).

Another pregnancy aside is that it is the initial increase in plasma volume during early pregnancy that is believed to be the main cause of the ‘natural performance enhancement’ of pregnancy. Please see my previous iRunFar article on running during pregnancy for more.

The luteal phase is certainly not all doom and gloom. There is good evidence for a decreased risk of injury during this phase. This has been especially well demonstrated in research on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) of the knee (Yu, 1999; Herzberg, 2017). It is believed that the increased progesterone levels of the luteal phase counteract the ligament-loosening effects of estrogen (Yu, 2001), likely protecting a female from many kinds of injuries–not just ACL injuries. The risk of ligamentous injury can also apparently be mitigated by the use of birth-control pills (Herzberg, 2017) via progesterone from the pills counteracting estrogen.

The Effects of Birth Control on Endurance-Running Performance

It is, at this point, unclear if and by how much monophasic birth-control pills affect exercise performance. One study by Bryner et al in 1996 found no significant effect (of low-dose norethindrone) and one study did find a 7% decrease in maximal exercise capacity in well-trained athletes after six months of monophasic therapy (Notelovitz, 1987).

Triphasic birth-control pills (with changing hormone levels over the course of the month) have consistently been shown to to decrease aerobic capacity (Casazza, 2002; Lebrun, 2003 ). The reasons for this are theoretical at this point, but may include weight gain, increased levels of progesterone compared with normal, increased progesterone-to-estrogen ratio, and exogenous (not natural) use of estrogen and progesterone suppressing the release of testosterone.

Depo-Provera birth control is progesterone-only and induces an estrogen-deficient state and is thus not recommended in athletes–or in any women in my opinion. Not only would aerobic performance likely be negatively impacted, but also the major risk of progesterone-only birth control is the loss of bone-mineral density (and not to mention a loss of libido and the gaining of hair in places you may not desire hair!)

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are essentially–or totally in the case of copper IUDs–hormone-free and are not expected to affect exercise performance. An interesting side note about hormonal IUDs is that, though around 20% of women may stop getting their period (Lähteenmäki, 2000), most of these amenorrheic women continue to have monthly cycles (Scholten, 1989) and all, at least in one study (Barbosa, 1990), maintained estrogen levels on par with those of a normal cycle.

The Effects of Amenorrhea on Endurance-Running Performance

But, oh my gosh, this is all just one big roller coaster! Let me off?

Would it not be better if women’s hormones did not fluctuate and they could just train the same all the time? Well, actually, in the case of amenorrhea (the loss of menstruation and monthly cycles), the answer appears to be a resounding no. Women who lose their period due to exercise/weight/dietary issues tend to end up in a chronically estrogen-depleted state. Estrogen, as previously described, is not only associated with aerobic-performance advantages, but is also known to influence muscle-contractile properties, muscle repair, regenerative processes, and post-exercise muscle damage.

Secondary functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (SFHA) (the loss of the period due to energy deficiency) is quite common among female athletes in weight-sensitive sports (Ciadella-Kam, 2014; Louks, 2007; Melin, 2014: Nattiv, 2007; Pollock, 2010). One study found a prevalence of 43% of female runners having menstrual dysfunction and 12% having total cessation of their period (De Souza, 1998).

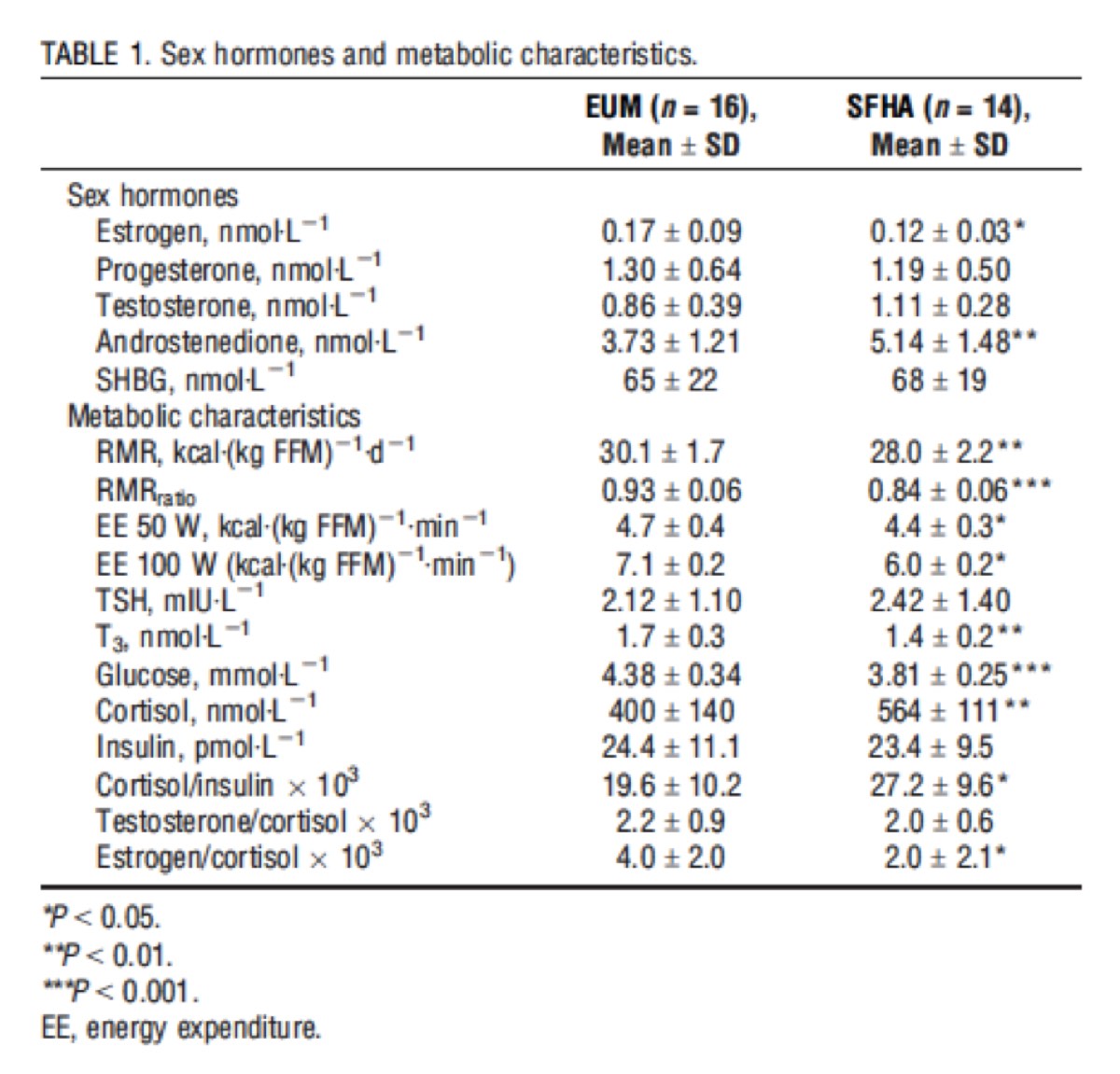

Amenorrhea in pre-menopausal women has a number of negative effects that are far from limited to loss of bone-mineral density and increased risk of osteoporosis (Ciadella-Kam, 2014; Nattiv, 2007; Schied, 2009). A loss of the menstrual cycle appears to cause an increased risk of injury (Rauh, 2006; Enns, 2010), delayed recovery (Enns, 2010), low energy (Louks, 2003), low thyroid hormone, and increased cortisol levels (the major stress hormone) (Gordon, 2010; Louks, 2007; Louks, 2003; Nattiv, 2007; Thong, 2000; Warren, 2011). See Figure 7’s hormone-level comparisons.

Figure 7. The levels of various hormones in eumenorrheic (EUM) women (who get their period regularly) and secondary functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (SFHA) – or loss of period secondary to exercise/low energy availability. This is a very busy table, but the most important takeaway points are the highly significantly increased cortisol levels in the amenorrheic women as well as the significant decrease in estrogen in amenorrheic women (Tornberg, 2017).

Additionally, in a study by Tornberg in 2017, both knee muscular strength (flexion and extension) and knee muscular endurance (repeated flexion and extension) was found to be significantly higher in the women who had regular menstruation. Another study (Fahrenholtz, 2018) found athletes with menstrual dysfunction spent more time in a catabolic state (where they were breaking down muscle) compared to regularly menstruating athletes, and again, this may be due to a lack of estrogen (and possibly also testosterone), but may also simply be due to inadequate energy availability. So yeah, getting your period may have its inconveniences, but it’s important to remember all of the health benefits it provides.

Menopause’s Effects on Endurance-Running Performance

Of course, at some point, women lose their period naturally and go through menopause. The average age for women to enter menopause is 51 in the United States, but may begin as early as age 40 (Mayo Clinic, 2018). (If you are found to have entered menopause before age 40, it is called premature ovarian failure.)

Though it may be presumed that endurance performance declines with advanced age, the best 100-kilometer running times were observed for women between 30 and 54 years (Knechtle, 2012) and may extend to later years as the number of post-menopausal female endurance runners increases. I imagine all of us have a handful of female runners over the age of 50 who we look up to and who continue to inspire us with their performances.

In practical terms, research continues to suggest that hormone-replacement therapy (HRT), combined with exercise, may be the most beneficial method for preserving muscle mass and strength in older women (Sipila, 2003; Meeusen, 2000). Several recent studies that found positive effects of HRT use in postmenopausal women on muscle mass, function, and protection from exercise-induced damage (Ronkainen, 2009; Onambele-Pearson, 2009; Dieli-Conwright, 2009). Unfortunately, there are significant drawbacks to HRT in older females including an increased risk of breast cancer (with combined estrogen and progesterone therapy), lung and colon cancer, stroke, blood clots, and heart attack. A nice summary of the research regarding the benefits and risks of HRT can be found at the National Cancer Institute website.

I was quite curious when I started researching for this article about testosterone horomone replacement as this has recently come into vogue among aging women. Despite the potential of testosterone to increase lean muscle mass, strength, bone density, and libido (Huang, 2013), as well as improved mood in women (Finkelstein, 2013; Tiyagi, 2017), it is, first of all, important to remember that it as well as its synthetic substitutes are on the World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) list of prohibited substances and methods. Its effects in men cannot necessarily be extrapolated to women. Unlike in men, there is not a well-defined optimal testosterone level in women. Measuring testosterone levels in women is not very reliable due to very low baseline levels compared with men which render current testing methods less accurate (Miller, 2004). Finally, the long-term effects of testosterone supplementation in females is currently not known (Tiyagi, 2017), but an increased risk of liver tumors, stroke, heart attack, and death has been found in men (Westaby, 1977; Vigen, 2013).

Figure 8. Testosterone level cycling in women compared with estrogen and progesterone (from https://www.restartmed.com/high-progesterone-symptoms/).

Recommendations

What specifically can women do to take advantage of their physiology to improve their endurance and strength?

Considering all of the above information, my personal interpretation is it would be wise for women to have predominantly aerobic training runs and races (800 meters or longer) in the follicular phase of the cycle and focus more on cross training, shorter interval training, or less-intense long runs in the luteal phase. Personally, I have found that the few days immediately before my period starts, when estrogen is decreasing rapidly, my normal workouts get frustratingly difficult and this is more of an indication for me that my period is coming than any other pre-menstrual symptoms. (I have also heard from numerous other women with similar experiences.)

For women who have ligament laxity, repeated subluxations, or are hypermobile, trialing a monophasic birth-control pill may be beneficial for injury prevention. This is because the progesterone in these pills has been found to be protective of ligamentous injury. Alternatively, women can opt to perform training that is more likely to be injurious during the luteal phase of the cycle when progesterone is highest.

A world-renowned expert in this field and co-author of Running for Women, Jason Karp, PhD, kindly agreed to be interviewed for this article. His advice to women regarding training according to their cycle is: “The best way to adjust training around the menstrual cycle is to push the endurance training (mileage, longer runs, tempo runs) during the estrogen-dominant follicular phase, and do less training during the progesterone dominant luteal phase… The biggest effect of the cycle seems to be on endurance performance because estrogen influences metabolism to rely more on fat and less on carbohydrate.”

If you are also a busy woman (perhaps a full-time job or multiple jobs, family commitments, and more), you might be thinking to yourself, I train whenever I can find time regardless of the phase of my cycle! I think that is totally okay. But it is also helpful to be aware that there are certain times where it is normal and even expected to feel ‘off’ or ‘less on.’ Don’t be too hard on yourself.

In terms of amenorrhea, it strongly behooves female athletes who have lost their period (and are not pregnant ;-)), to get it back. All females should consult their physician if they have stopped menstruating younger than the age of 40.

For menopause, I am unable to make a blanket statement about whether or not a post-menopausal woman should take HRT. The overall risks and benefits of HRT should be considered on an individual basis between a woman and her physician. It should be noted that the vast majority of women on HRT after menopause take it for moderate to severe post-menopausal symptoms, and not to improve athletic ability. In case the obvious needs to be said, women who actively compete in races and who are found by their physicians to need WADA-prohibited forms of HRT must work with their physician to follow WADA therapeutic-use exemption protocol.

Interview with ‘The Queen’

Many readers are familiar with Meghan Laws (formerly Arbogast), often referred to as ‘The Queen,’ who is a 57-year-old ultrarunner from Cool, California. She continues to outrun most of her younger competition and just ran for the American team at the 2018 IAU 100k World Championships. Despite having an off race for her, she won her age group. And in 2017 she was able to, once again, place in the top-10 females at the Western States 100. I see her training and racing often, and she is a very sweet and down-to-earth presence on the trails. I have secretly wondered if she ‘needed’ HRT to continue to train and race at the level she does. For this article, she kindly shared her ‘secrets; with me:

“I think partly, I don’t train super hard in terms of intensity–lots of slow, easy running. I do tend to get eight to 10 hours of being horizontal–I’m not the greatest sleeper, but just the rest is good. I avoid junk food, highly processed food. I love whole foods, salads, meats, vegetables. No strict guidelines–I tend to gravitate to healthy food. I take maca root, a supplement called Sleep from NOW foods, one called Mental Focus, and one called Mannose Cranberry… no hormone replacement.”

In terms of her ‘secret,’ she concluded, “I think mostly consistent training. Diet plays a role, the supplements–kind of hard to tell, really. Having other things to do every day like chores, taking care of our animals and property, and playing the flute all contribute to a more balanced life.”

Pretty simple. Or is it? This is a woman who takes care of herself.

Conclusion

All women should play the flute. Or, if not the flute, maybe we should all spend time contemplating what makes us thrive and do that!

I hope that this article has educated you about changes and processes that may or may not be occurring in your body. Perhaps you can either now further embrace what is happening or take steps to change potentially unhealthy behaviors. Personally, I think the importance of adequate sleep and nutrition cannot be underestimated. I also firmly believe that the more we learn about female physiology and how it relates to athletics, the better we can perform and the healthier and happier we can be.

In terms of research in female endurance sports, I feel we have only seen the very tip of the iceberg. As research in women’s sport continues to expand and improve, and larger, more high-quality studies are done, I am certain that additional strategies and new insights will arise and add significantly to the basic overview provided in this article. I firmly believe that the more we learn about female physiology and how it relates to athletics, the better we can perform and the healthier and happier we can be.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Women, would you like to share personal observations and anecdotes about how your running performance and your feelings during running vary throughout your monthly cycle?

The author (left) and Ann Trason at the 2015 Overlook Endurance Run 30k. Photo courtesy of Ann Trason.

References

Barbosa, O. Bakos, S.E. Olsson, et al. Ovarian function during use of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD Contraception, 42 (1990), pp. 51-66.

Bayliss DA, Millhorn DE, Gallman EA, Cidlowski JA. Progesterone stimulates respiration through a central nervous system steroid receptor-mediated mechanism in cat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84(21):7788-7792.

Bungo MW, Charles JB, Johnson PC. Cardiovascular deconditioning during spaceflight and the use of saline as a countermeasure to orthostatic intolerance. Aviat Space Environ Med 56: 985–990, 1985.

Brooks-Gunn J, Gargiulo JM, Warren MP. The effect of cycle phase in the performance of adolescent swimmers. Physician Sportsmed 1986; 14: 182-4 27.

Bryner RW, Toffle RC, Ullrich IH, Yeater RA. Effect of low dose oral contraceptives on exercise performance. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;30(1):36-40.

Casazza, Gretchen & Suh, Sang-Hoon & Miller, Benjamin & M Navazio, Franco & Brooks, George. (2002). Effects of oral contraceptives on peak exercise capacity. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 93. 1698-702.

Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Modification of active cutaneous vasodilation by oral contraceptive hormones. J Appl Physiol 83: 2012–2018, 1997. 5.

Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Reflex control of cutaneous vasoconstrictor system is reset by exogenous female reproductive hormones. J Appl Physiol 87: 381–385, 1999.

Cialdella-Kam L, Guebels CP, Maddalozzo GF, Manore MM. Dietary intervention restored menses in female athletes with exercise-associated menstrual dysfunction with limited impact on bone and muscle health. Nutrients. 2014;6:3018–39.

Convertino V. A. Blood volume: Its adaptation to endurance training. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1991;23(12):1338–1348.

Coyle EF, Hopper MK, Coggan AR. Maximal Oxygen Uptake Relative to Plasma Volume Expansion. Int J Sports Med 1990; 11(2): 116-119.

Davies BN, Elford JC, Jamieson KF. Variations in performance in simple muscle tests at different phases of the menstrual cycle. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1991; 31 (4): 532-7 28.

De Souza MJ, Miller BE, Loucks AB, et al. High frequency of luteal phase deficiency and anovulation in recreational women runners: blunted elevation in follicle-stimulating hormone observed during luteal-follicular transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83 (12): 4220-32.

Dieli-Conwright CM, Spektor TM, Rice JC, et al. Influence of hormone replacement therapy on eccentric exercise induced myogenic gene expression in postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol 2009; 107: 1381-8 98.

Enns DL, Tiidus PM. The influence of estrogen on skeletal muscle: sex matters. Sports Med. 2010;40:41-58.

Fahrenholtz, I. L., Sjödin, A., Benardot, D., Tornberg, Å. B., Skouby, S., Faber, J., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., Melin, A. K.Within-day energy deficiency and reproductive function in female endurance athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 28(3); 0905-7188.

Gordon CM. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med.2010;363(4):365–71.

Herzberg SD, Motu’apuaka ML, Lambert W, Fu R, Brady J, Guise J-M. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle and Contraceptives on ACL Injuries and Laxity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;5(7).

Julian R, Hecksteden A, Fullagar HHK, Meyer T. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on physical performance in female soccer players. Lucía A, ed. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173951. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173951.

Herzberg SD, Motu’apuaka ML, Lambert W, Fu R, Brady J, Guise J-M. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle and Contraceptives on ACL Injuries and Laxity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;5(7):2325967117718781. doi:10.1177/2325967117718781.

Hiroshoren NT, Makrienko I, Edoute I, Plawner Y, Itskovitz-Eldor MM, Jacob J. Menstrual cycle effects on the neurohumoral and autonomic nervous systems regulating the cardiovascular system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 1569 –1575, 2002. 18.

Houghton BL, Holowatz LA, Minson CT. Influence of progestin bioactivity on cutaneous vascular responses to passive heating. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37: 45–51; discussion 52, 2005.

Huang, G. MD et. al. “Testosterone Dose-Response Relationship in Hysterectomized Women With or Without Oophorectomy: Effects on Sexual Function, Body Composition, Muscle Performance, and Physical Function in a Randomized Trial.” The North American Menopause Society (2013): 612-624.

Janse de Jonge XA. Effects of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance. Sports Med. 2003; 33(11):833-51.

Janse De Jonge XA Thompson MW, Chuter VH Silk LN, Thom JM. Exercise performance over the menstrual cycle in temperate and hot, humid conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(11):2190–8.

Karp J, Smith C. Running for Women. 1st Edition. Human Kinetics. 2012.

Klarlund-Pedersen B. Graviditet og Motion. 2nd Edition. Copenhagen. Nyt Nordisk Forlag. 2012.

Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Age-related changes in 100-km ultra-marathon running performance. Age. 2012;34(4):1033-1045. doi:10.1007/s11357-011-9290-9.

Lebrun CM, McKenzie DC, Prior JC, Taunton JE. Effects of menstrual cycle phase on athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(3):437–44.

Lebrun, CM et al. “Decreased Maximal Aerobic Capacity with Use of Triphasic Oral Contraceptive in Highly Active Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” British Journal of Sports Medicine (2003): 315-320.

Loucks AB, Thuma JR. Luteinizing hormone pulsatility is disrupted at a threshold of energy availability in regularly menstruating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(1):297–311.

Loucks AB. Energy availability and infertility. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14:470–4.

Lowe DA, Baltgalvis KA, Greising SM. Mechanisms behind Estrogens’ Beneficial Effect on Muscle Strength in Females. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2010;38(2):61-67. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181d496bc.

Lähteenmäki P, Rauramo I, Backman T. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system in contraception. Steroids. 2000;65:693–7.

Meeuwsen IB, Samson MM, Verhaar HJ. Evaluation of the applicability of HRT as a preservative of muscle strength in women. Maturitas 2000; 36: 49-61

Melin A, Tornberg ÅB, Skouby S, et al. The LEAF questionnaire: a screening tool for the identification of female athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:540–5.

Miller KK, Rosner W, Lee H, Hier J, Sesmilo G, Schoenfeld D, Neubauer G, Klibanski A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Feb; 89(2):525-33.

Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(10):1867–82.

Notelovitz M, Zauner C, McKenzie L, Suggs Y, Fields C,and Kitchens C. The effect of low-dose oral contraceptives oncardiorespiratory function, coagulation, and lipids in exercising young women: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 156:591-598, 1987.

Oian P, Tollan A, Fadnes HO, Noddeland H, Maltau JM. Transcapillary fluid dynamics during the menstrual cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol 156: 952–955, 1987.

Onambele-Pearson, GL. HRT affects skeletal muscle contractile characteristics: a definitive answer? J Appl Physiol 2009; 107: 4-5 99.

Oosthuyse T, Bosch AN. The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise metabolism: implications for exercise performance in eumenorrhoeic women. Sports Med. 2010;40(3):207–27.

Pollock N, Grogan C, Perry M, et al. Bone-mineral density and other features of the female athlete triad in elite endurance runners: a longitudinal and cross-sectional observational study. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20:418–26.

Redman LM, Weatherby RP. Measuring performance during the menstrual cycle: a model using oral contraceptives. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004; 36 (1): 130-6.

Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Trone DW, Shaffer RA, Brondine SK. Epidemiology of stress fracture and lower-extremity overuse injury in female recruits. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(9):1571–7.

Ronkainen PH, Kovanen V, Alen M, et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy modifies skeletal muscle composition and function: a study with monozygotic twin pairs. J Appl Physiol 2009; 107: 25-33.

Scheid JL, Williams NI, West SL, VanHeest JL, De Souza MJ. Elevated PYY is associated with energy deficiency and indices of subclinical disordered eating in exercising women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. Appetite. 2009;52(1):184–92.

Scholten PC. The levonorgestrel IUD. Clinical performance and impact on menstruation. Utrecht: University of Utrecht, 1989. p. 94. Thesis.

Sims ST, Rehrer NJ, Bell ML, Cotter JD. “Pre-exercise sodium loading aids fluid balance and endurance for women exercising in the heat.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 103: 534–541, 2007.

Sipila S, Poutamo J. Muscle performance, sex hormones and training in peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2003; 13: 19-25 34.

Smith GI, Yoshino J, Reeds DN, et al. Testosterone and Progesterone, But Not Estradiol, Stimulate Muscle Protein Synthesis in Postmenopausal Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99(1):256-265. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2835.

Stachenfeld NS, Silva C, Keefe DL, Kokoszka CA, Nadel ER. Effects of oral contraceptives on body fluid regulation. J Appl Physiol 87: 1016 –1025, 1999.

Sung E, Han A, Hinrichs T, Vorgerd M, Manchado C, Platen P. Effects of follicular versus luteal phase-based strength training in young women. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:668. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-668.

Thong FS, McLean C, Graham TE. Plasma leptin in female athletes: relationship with body fat, reproductive, nutritional, and endocrine factors. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;88:2037–44.

Tornberg ÅB, Melin A, Koivula FM, Johansson A, Skouby S, Faber J, Sjödin A. Reduced Neuromuscular Performance in Amenorrheic Elite Endurance Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Dec;49(12):2478-2485.

Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, Grunwald GK, Maddox TM, Bradley SM, Barqawi A, Woning G, Wierman ME, Plomondon ME, Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013 Nov 6; 310(17):1829-36.

Yu WD, Liu SH, Hatch JD, Panossian V, Finerman GA. Effect of estrogen on cellular metabolism of the human anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999 Sep; (366):229-38.

Yu WD, Panossian V, Hatch JD, Liu SH, Finerman GA. Combined effects of estrogen and progesterone on the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001 Feb; (383):268-81.

Zingg MA, Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Rüst CA. Performance differences between sexes in 50-mile to 3,100-mile ultramarathons. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;6:7-21.