I woke up in the dim light of dawn to the feeling of something wet. I pulled up the blanket and, to my horrid realization, there was blood on the sheets between my legs. I was pregnant, about six weeks along, and knew I was having a miscarriage. I started crying and woke up my husband, Rasmus. “I’m bleeding!” “No! Are you sure?” He and I went to the bathroom and the blood was literally gushing into the toilet. We were in shock. We were on vacation in Duluth, Minnesota, and two days ago I had run the Voyageur 50 Mile, slow and easy. The next day we had gone on a beautiful, easy bike ride and I felt great. Now, here we were, both crying, wondering if the 50 miler was the cause of the miscarriage. Yet it made no sense–I had consistently run 90 to 110 miles per week during my first pregnancy, which was entirely uncomplicated and, in fact, wonderful! I had also run many 50 milers before, at much faster paces. It just didn’t add up. Why, why, why? Why was I having a miscarriage?

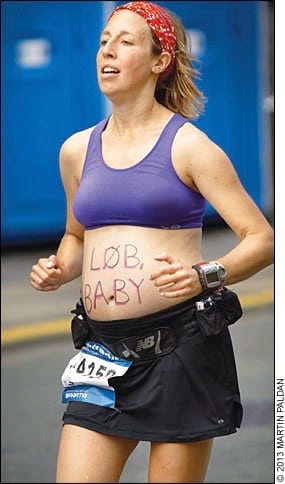

Author Tracy Hoeg running the 2011 Copenhagen Marathon at 30 weeks pregnant with her son, Mattias. Photo: Martin Paldan

In complete desperation, 99% certain this was irreversible, we went to a local emergency department (ED). The intake nurse was very friendly and I explained to her that I was having a miscarriage and told her I had run the Voyageur 50 Mile two days ago. “I doubt running that has anything to do with this,” she said kindly. “Running during pregnancy is healthy, right?” She asked me, since she knew I was a doctor. All I could think of was, “Yes, I used to think so.”

A radiology tech took us into a dark room to do an ultrasound scan. The ultrasound tech and the ED doctor concurred: “This baby stopped growing weeks ago. The fetus measures nowhere near the size it should be for six weeks of pregnancy, more like two weeks gestation (four weeks pregnancy).” Wow. This made so much more sense. Now I understood why my pregnancy tests had always only been faintly positive and why I had had essentially no nausea, shortness of breath, or fatigue. Thankfully, my husband and I and our family and friends would not forever blame the ultramarathon–or me.

For the record, I went on to run six marathons and one ultramarathon in my next pregnancy, which was uncomplicated, and our second son, Mattias, is as healthy and happy as his older brother, Christian.

Eleven to 22% (Ammon Avalos, 2012) of all recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage. At some point, women who run, walk, lift weights, eat cheese, let a puppy sit in their lap, or wear bright purple scarves will have a miscarriage and blame themselves and whatever they just happened to do for the miscarriage. Similarly, pregnancy complications happen and, for women who run, they (or someone else) will blame their running if complications do develop. Whereas, if women remain sedentary, despite the known risks of lack of exercise to the mother and baby, they are less likely to be blamed or to self-blame.

[Author’s Note: The percentage of miscarriage varies by age group and study population, with women over 35 years of age experiencing the highest rates.]

Background

Western women have been prescribed bed rest for various pregnancy complications since the age of Hippocrates. However, prior to the 20th century, this was rarely practiced, as women could usually not afford to stop working or care for their children or families. (Prior to Hippocrates, this was also very unlikely to have been practiced, given humans’ nomadic lifestyle and the need for women to hunt, gather, perform manual labor, and travel.) In the 1800s, however, bed rest became a popular medical practice for post-operative pain management, hysteria, and other mental illnesses (the “Rest Cure” specifically made for women, as opposed to the much more active “West Cure” for men) as well as for prevention and treatment of obstetrical complications. These were empirical treatments and not based on evidence of benefit. Over the next 100 years, the detrimental effects of bedrest began to surface, including loss of strength and endurance, osteoporosis, degenerative joint disease, increased heart rate, decreased cardiac reserve, orthostatic hypotension, and life-threatening blood clots (Dittmer, 1993). Additional risks to the offspring of pregnant mothers included decreased fetal growth and increased risk of childhood allergies, motion sickness, and decreased ability to self-calm in offspring (Bigelow & Stone, 2011).

[Author’s Note: One of the biggest misconceptions about running in pregnancy is that you are going to be ‘jostling the baby around too much,’ which is certainly not the case as they are entirely enveloped and very protected in a pool of embryonic fluid, and that movement is likely necessary for proper development of the vestibular system. And some aspect of exercise, be it movement itself or increased blood flow, aids in a baby’s ability to self-calm after birth. For parents who desire a good night’s sleep, this is a big deal.]

According to a review of the available scientific literature from 2011, Bigelow and Stone found there were no complications of pregnancy for which bed rest was shown to be beneficial. They conclude that the physical and psychological adverse effects on mother, family, and neonate make it contraindicated for any pregnancy complications or conditions. However, in our current decade, 95% of obstetricians still prescribe activity restriction to pregnant mothers for a variety of reasons (Bigelow & Stone, 2011), thereby continuing to falsely promote the idea that rest is safer and activity less safe.

Be that as it may, while cardiovascular exercise has overwhelming evidence behind its positive effects on maternal and fetal health (as I will cover below), women who work long hours of manual labor, spend prolonged time standing, or performing heavy lifting appear to have slight but significant increase in the odds of preterm labor and possibly of gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes (Bonzini, 2007). Leisure-time exercise, however, appears to have entirely different and beneficial physiologic effects compared with prolonged, difficult manual labor. If it is hard to understand why these two would affect a pregnant woman so differently, simply think of the positive effects that leisure-time exercise has on non-pregnant humans compared with the negative effects of prolonged, difficult manual labor or working duties.

Scientific consensus, even in the early 1980s, was that women could (and probably should be encouraged to) continue to exercise at their pre-pregnancy level of physical fitness (Bullard, 1981). As early as 1962, Dr. Erdelyi, matched 172 Hungarian pregnant female athletes with non-athletic controls and found that, among the athletic females, there was:

- A decreased rate of pregnancy complication

- The delivery was faster on average

- The rate of cesarian sections was half that of the control group (Erdelyi, 1962). Interestingly, a 1956 German study had already found a postpartum performance advantage in women who continued to exercise pregnant (Jokl, 1956). [Author’s Note: Many of you are likely aware of the pregnancy doping allegations of the 1970s and ‘80s in East Germany, where women would get purportedly pregnant and then have an abortion to improve their running performance.]

‘Back to the ‘80s:’ The Era of Groundbreaking Research

In 1980, Dr. Clapp started studying the pregnant ewe running on a treadmill. He noted that in the near-term ewe, intense exercise produced no changes in maternal-fetal blood exchange, as J. Orr from the University of Wisconsin had already discovered in ewes in 1972.

[Author’s Note: The reason the ewe is such a good animal model for the investigation of mother-to-fetus interactions is because of the ease with which you can place catheters to monitor maternal-fetal blood/nutrient exchange.]

But what Dr. Clapp also learned was it was not until “exhaustion” that lactic acid began to rise in the mother’s blood. And, even at exhaustion, uptake of oxygen by the fetus remained constant (Clapp, 1980). What he had discovered was an astounding degree of physiological fetal protection during intense pregnant running by ewes.

Meanwhile, women runners were busy doing their own self-experimentation. One of these was Ingrid Kristiansen, who unintentionally discovered in 1983 that it was possible to run a 2:33:27 marathon two months pregnant. This was just three minutes slower than her PR at the time. Following the race, she reportedly went on running 100-plus-mile weeks until she learned she was pregnant at five months along and then “trained as much as she could before the birth” (Moore, 1986). She gave birth to a healthy son and went on in 1985 to set the then-marathon world record with a time of 2:21:06. But her case was, of course, only anecdotal–was she just ‘lucky?’ Though she was certainly an outlier, she was indeed adhering to the advice of continuing to exercise at her pre-pregnancy level of fitness.

Ingrid Kristiansen with husband, Arve, and son, Gaute. Photo: Rob Bogaerts and with permission of the Dutch National Archives

In the mid ‘80s, Dr. Clapp switched from studying pregnant ewes to women. He organized a prospective case-control trial looking at 26 exercising women (runners and dance instructors) versus 26 non-exercising controls (who had previously exercised) and were matched for age and sociodemographic background. The “exercising” group exercised five or more times per week for 60 to 90 minutes at 65 to 90% maximum heart rate and the “non-exercising” controls were “physically active” but rarely engaged in sustained exercise but walked, gardened, and more.

Over the next decade, numerous benefits of continued aerobic exercise during pregnancy and an overwhelming paucity of risks (even theoretical) became clear and the findings were published in one landmark article after another. The medical community and general population have, unfortunately, lagged behind in recognizing these important beneficial effects of regular aerobic exercise in pregnancy. The studies and benefits he found are laid out in his book, Exercising Through Your Pregnancy.

Here are the benefits discovered over decades of research by Clapp et al:

- Less low-back, leg, or pelvic pain than controls (less than 10 versus greater than 40%)

- Decreased risk of cesarian section (nine versus 29%)

- Decreased pregnancy weight gain (which would later be correlated with decreased gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and cerebral palsy)

- Decreased postpartum weight retention (one third of the weight retention at one year compared with controls)

- Decreased risk of acute low-back injury (which resulted in an extended period of pain in physical limitation in a number of the non-exercising controls)

- 50% decreased risk of induction of labor

- Decreased risk of gestational diabetes

- Larger placenta with improved oxygen-delivering capability

- Lower fetal heart rate and increased fetal heart-rate variability (which are signs of good cardiovascular health)

- Babies with significantly increased ability to calm themselves as soon as five days after birth

- Offspring have significantly higher scores on intelligence testing

- Offspring have significantly better oral language skills

The Current State of Research of Exercise in Pregnancy

Twenty additional years of research have only added evidence to the above findings by Dr. Clapp. The current known benefits of exercise during pregnancy include:

- The same long-term medical and psychological benefits of exercise derived by non-pregnant individuals

- Maintenance or improvement of cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength and endurance, flexibility, and body composition (Artal, 2013; de Oliveria Melo, 2012; Price, 2012; Gavard, 2012)

- Maintenance or improvement in agility, coordination, balance, power, reaction time, and speed (Artal, 2013; de Oliveria Melo, 2012; Price, 2012; Gavard, 2012)

- Avoidance of excessive gestational weight gain (Muktabhant, 2012; Elliott-Sale, 2015; Perales, 2016)

- Prevention or reduction in severity of musculoskeletal symptoms, such as low-back pain and pelvic-girdle pain (Kluge, 2011; Liddle, 2015; Owe, 2016)

- Reduction in risk of newborns that are considered “too small” or “too large” (Wiebe, 2015)

- Reduction in risk of developing gestational diabetes (Artal, 2015)

- Decreased risk of preeclampsia with increasing levels of physical activity (Aune, 2014)

- Reduction in labor duration (Perales, 2016; Salvesen, 2014)

- Reduction in risk of cesarean delivery (Poyatos-Leon, 2015; Tinloy, 2014)

- Reduction in risk of preterm delivery (Hegaard, 2006; Juhl, 2008)

- Significantly increased VO2Max immediately and for 20 years or longer after their pregnancy; a moderate to high level of exercise during and after pregnancy appears to lead to an increase in VO2Max in the region of five to 10% after pregnancy (Wallace, 1991; McCrory, 1999)

Approximately 77% of nationally ranked runners and 61% of recreational runners currently continue to run during their pregnancy (Tenforde, 2015). Among women who stopped running when they leared they were pregnant, the majority (54.6%) did not feel well enough, 27.3% stopped running on doctor’s advice (doctor advised not to run or doctor advised non-weight bearing activities), and 21.2% did so for concern of miscarriage (Tenforde, 2015).

With the booming popularity of long-distance running and increasing cultural acceptance of running during pregnancy, we are gaining more and more anecdotal information about endurance training, long-distance running, and competitive running in pregnancy. However, despite the overwhelming evidence of health benefits of aerobic exercise in general during pregnancy, there exists very little in the way of guidelines about how much is too much (for mother and/or baby) and this instills fear in all athletic levels of exercising women. There are simply no high-quality studies looking at pregnancy outcomes in women who run long distances or at high intensities. (Granted, 60 to 90 minutes/day five or more times a week at 65 to 90% maximum heart rate as analyzed in the Clapp studies is vigorous and intense by most standards). A prospective randomized trial of high-intensity versus low-intensity running would not be ethical or acceptable, as pregnant women would and should not be forced to run a lot or a little. The best type of study design would be a prospective cohort study, such as that done by Dr. Clapp, this time looking at women who choose to run high mileage/high intensity (though less than 90% maximum heart rate) and compare their outcomes to women who choose pre-pregnancy to do minimal to moderate exercise. Retrospective survey studies would be too likely to be flawed with recall bias from women with intense training regimens underreporting miscarriages or negative outcomes.

In the meantime, what may be most comforting for female runners who wish to continue running during pregnancy is clarification on points of doubt and recommended precautions.

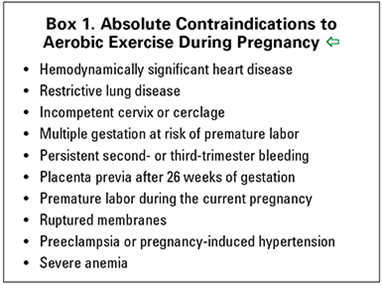

Absolute and Relative Contraindications to Aerobic Exercise in Pregnancy

First, the American College of Gynecology has put out the following contraindications to running during pregnancy:

Here’s terminology from the figure broken down to simpler terms:

- Hemodynamically significant heart disease- Heart disease that causes your blood pressure or heart rate to be abnormally and dangerously low or high

- Restrictive lung disease- A disease which compresses or restricts the lung tissue thereby decreasing oxygen uptake with breathing

- Incompetent cervix or cerclage- A cervix that is opening or not fully closed (outside of labor); a cerclage is a suture technique that holds the cervix shut

- Placenta previa- When the placenta sits at least partially over the opening of the uterus to the cervix and often causes bleeding

- Premature labor- Any labor before 38 weeks

- Ruptured membranes- ‘The water broke’

- Pre-eclampsia- Pregnancy-induced high blood pressure most often accompanied by decreased kidney function

- Severe anemia- Anemia so profound that it causes symptoms (such as elevated heart rate and shortness of breath)

As you will note, the list is short and the reasons not to exercise or run, if you have one of these conditions, seem inherently obvious, also for non-pregnant humans.

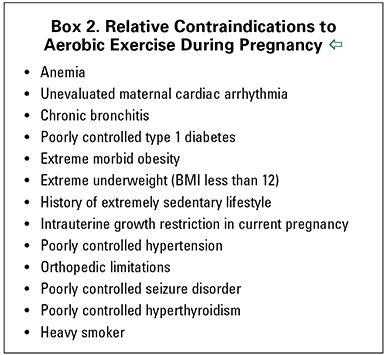

Box 2 from the American College of Gynecology lists “relative contraindications,” which are all medical conditions that require treatment before an exercise regimen is developed. First, it is important to note that many women become slightly anemic (greater than 40%, according to Tanner, 2015) during pregnancy and mild anemia, while it should be treated, should not be a contraindication to aerobic exercise.

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or fetal weight that is below the 10th percentile for expected size in utero, is one exception to this. The theoretical concern is that exercise decreases blood flow and nutrients to the fetus. However, I cannot find any studies looking at the direct effect of exercise on IUGR. Given the placenta of exercising mothers enlarges and is on average capable of delivering more blood to the baby, exercise could theoretically promote growth in these babies. This is a topic women need to discuss with their doctors until research on the effects of exercise on IUGR is done.

Points of Concern

Additionally, I have compiled a list of a few points of concern specifically for trail and long-distance runners:

Elevated Core Temperature and Neural-Tube Defect Risk

The risk of a neural tube defect appears to increase with a rise in body temperature (Milunsky, 1992). The fetal neural tube (the fetal precursor of the brain and spinal cord) is formed 35 to 42 days from the last menstrual period. Exposure to increased core body to above 103°F (39°C) in this time period could increase the risk of fetal neural tube defects (Chambers, 2006). Higher body-core temperature could be reached during intense exercising, especially in a hot and humid environment, and should be avoided 35 to 42 days after the last menstrual period (or 21 to 28 days gestation). Exercising at less than 85% maximum heart rate should not raise core temperature to greater than 39°C, if the ambient temperature is not hot and there is adequate opportunity for heat dissipation. The pregnant body has an improved capacity for heat dissipation and a lower baseline temperature (Clapp, 2013). Importantly, if in doubt during this time period, carry a thermometer. Keep in mind rectal temperature is recorded in the rectum. This is important because during pregnancy, there are an increased number of blood vessels on the skin, which allows for improved heat dissipation, but skin temperature in pregnancy is falsely elevated three to 10°F compared with core temperature (Clapp, 2013), so rectal temperature is much more reliable!

Miscarriage

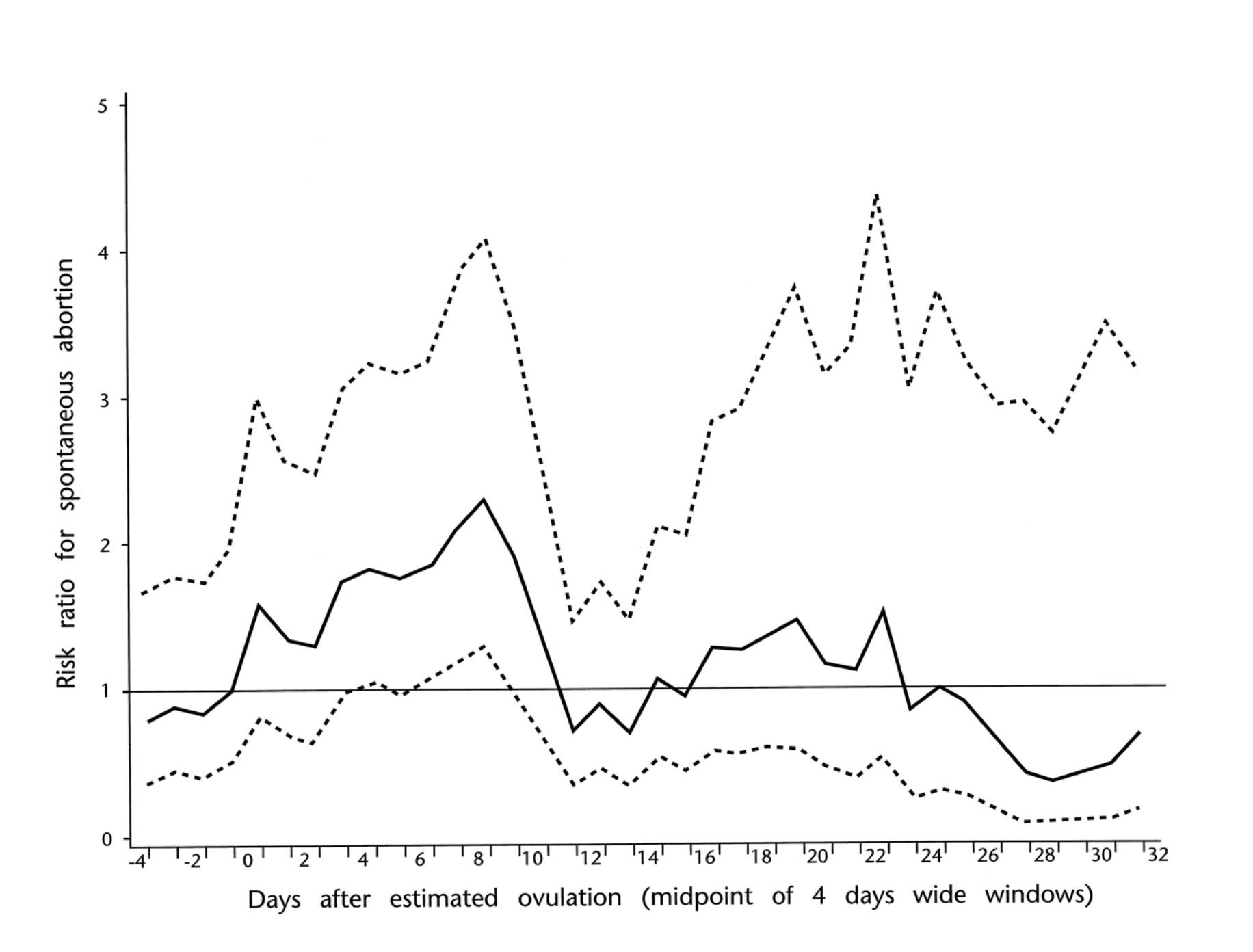

One Danish study (Hjollund, 2000) found there may be a slight increase in miscarriage if strenuous exercise occurs on the day of embryonic implantation (gestational age six to nine days; or 20 to 23 days after the last menstrual period). It should also be noted that, if this risk is there, it is slight and this risk is not increased in exercisers through the rest of the pregnancy.

From Hjollund (2000), the plot is miscarriage risk versus days after estimated ovulation. The black line is strenuous exercisers compared with 1, the risk of controls. The dashed lines are confidence intervals.

Preterm Birth

Despite worries about increasing the risk of preterm birth with exercise, the opposite has been shown consistently in high-quality studies (Hegaard, 2006; Juhl, 2008). One high-quality study (Hegaard, 2006) found the odds of birth to be 66% lower (Odds ratio=0.34; Confidence interval=0.14 to 0.85) in those who participated in moderate to heavy physical activity compared to non-exercising women.

Exercise to Maximum Effort/Exhaustion

Three standard tests of near-maximum exercise capacity in pregnancy exist. Harmful effects on mother or fetus have not been reported after these tests. However, one Norwegian (Salvesen, 2012) and one American (Szymanski, 2012) study showed a worrisome slowing of fetal heartrate with treadmill running above 90% of maximum maternal heart rate, which quickly normalized on cessation of exercise. The effect of brief or prolonged exercise at this intensity during pregnancy is not known and is currently not recommended. As noted in the Clapp study of pregnant ewes, fetal oxygenation was maintained. However, any type of exercise above 90% maximum heart rate at any point in pregnancy is not recommended.

Altitude

Symptom-limited exercise tests were conducted in seven healthy pregnant women at 33 to 34 weeks gestation at sea level and, within a week, at an altitude of 6000 feet, after a rapid ascent. There were no worrisome effects on the fetus (Artal, 1995). The Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology in Canada states there is no evidence of adverse effects with moderate exercise at altitudes of up to 2,500 meters (8,200 feet). It is generally recommended that women acclimate for two to three days prior to resuming exercise at higher than 6,000 feet, due to theoretical concerns of decreased oxygen delivery to the fetus. Babies born to mothers who live at higher altitude have been found to weigh less at birth. Babies are expected to weight 102 grams (3.60 ounces) less per 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) of altitude increase above sea level (Jensen & Moore, 1997); this is the average and may vary widely from woman to woman.

Fetal Weight Gain

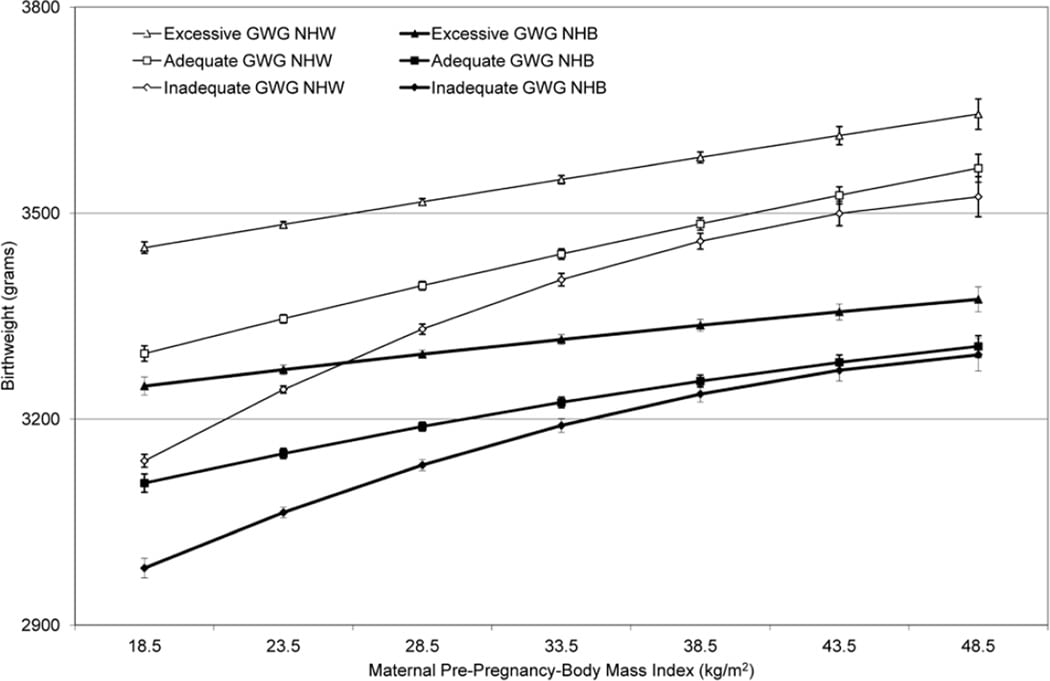

It may seem that exercise would be a risk factor for delivering smaller babies. However, this has not been found to be the case. Exercise during pregnancy has been found to promote appropriate birth weight in offspring. Women who exercise regularly during pregnancy have a decreased risk of delivering both large-for-gestational-age and small-for-gestational-age babies (Juhl, 2010; Weibe, 2015). However, many women who exercise have lower Body Mass Indices (BMIs). The correlation between pre-pregnancy BMI with baby’s birth weight, stratified by amount of pregnancy weight gain is shown below:

From Hunt KJ, Alanis MC, Johnson ER, et al (2013), maternal pre-pregnancy weight and gestational weight gain and their association with birthweight with a focus on racial differences.

Balance/Falling/Getting Injured and Being Far from Medical Care

It does not take a research study to figure out that driving to a remote locale for a mountain run during pregnancy could become disastrous if you are far from medical care, especially if you are alone. Your center of gravity is altered during pregnancy, which increases fall risk. However, there does not appear to be an increased rate of falls in regularly exercising versus non-exercising women (Clapp, 2013), though this is likely is dependent on mode of exercise and terrain.

Urinary Incontinence

Pregnant women runners will certainly notice that urinary urgency and frequency quickly affect how long, how fast, and where they run. Some women have told me that it is the constant need to urinate that keeps them from running while pregnant. Women may be reassured that a study of Norwegian elite athletes did not find their rates of postpartum urinary incontinence to be different than non-exercising controls (Bø, 2007). But many women leak urine postpartum and probably not all who do admit it–I personally ran with a maxi pad for a couple of months postpartum for this reason. (Don’t forget to do your Kegel exercises!)

Pelvic and Low-Back Pain

Many women cite pelvic, hip, or low-back pain as a reason they stop running during pregnancy. However, interestingly, women who reported high-impact exercise three to five times per week before pregnancy had a 14% lower risk of developing severe pelvic, hip, or low-back pain in pregnancy compared with non-exercisers. Only one study has investigated pelvic and low-back pain in elite athletes, reporting a prevalence of 29.6% for pelvic/hip and 18.5% for low back during pregnancy, similar to non-athletic controls (Bø, 2007).

Reassurance

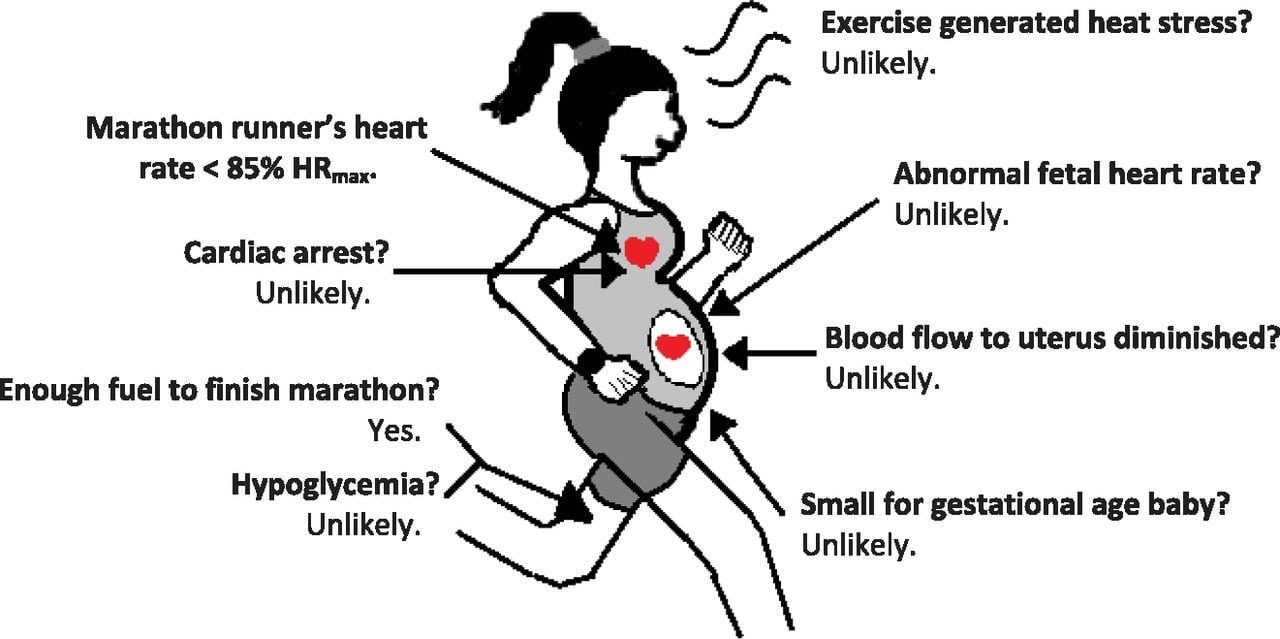

For women who can regularly run marathon and ultramarathon distances prior to pregnancy, running them in a non-competitive way during pregnancy appears to be “no big deal” (of course provided they do not have any contraindications to running). This is not surprising from a physiological standpoint, provided the runner does not go above 90% maximum heart rate (listed as 85% because of the early first trimester concern for exposing the developing brain and spinal cord to excess heat). For further details on the physiological adaptations to exercise in pregnancy and the explanation to why running a marathon at 39 weeks into a pregnancy is “no big deal,” see the excellent article from the Journal of Applied Physiology.

From Zavorsky et al (2012), concerns of completing a marathon while pregnant, debunked. Figure created by Allison M. Straub.

As shown above, concerning a woman running a marathon pregnant: fetal heart rate has not been found to be abnormal when maternal heart rate is below 90% maximum. Similarly, blood flow to the uterus and umbilical oxygen delivery is not expected to be affected below this heart rate. Exercise-generated heat stress is unlikely given the pregnant body’s improved ability to dissipate heat and lower set temperature, especially if it is not hot (approximately less than 80°F depending on the humidity) and the runner is able to carry on a conversation while running without losing her breath. Cardiac arrest during a marathon is highly improbable and it is not expected to be different than the incidence in the general population of 0.00016%. Finally, women who exercise regularly while pregnant should not worry about having a small-for-gestational-age infant. Regular exercise promotes appropriate size at birth and is dependent on maternal weight and maternal weight gain.

Interviews

One of the most important reassuring factors for pregnant women who wish to run is having mentors who have run through a pregnancy or two and can offer advice and reassurance. I interviewed Michele Yates and Alicia Vargo about running and training during their pregnancies for this article. They are both amazing potential mentors for women reading this who wish to continue running or training at high levels during their pregnancy.

Michele Yates

Michele Yates has a 34:16 10k PR (2009), a 1:17:23 half-marathon PR (2009), and a 2:38:37 marathon PR (2009). She’s twice competed in the Olympic Marathon Trials, she’s won four USATF national championships in ultramarathon distances, was the 2013 The North Face Endurance Challenge 50-Mile Championships winner, and was UltraRunning Magazine’s 2013 (North American) Ultrarunner of the Year.

I got to know her when we shared a room in Wales at the 2013 IAU Trail World Championships while competing for Team USA. She got pregnant shortly thereafter in 2014. She continued to run about 80 miles per week during her entire pregnancy (though slightly less during the first trimester due to excessive fatigue (necessitating 15 to 17 hours of sleep a day, which turned out to be at least partially caused by undiagnosed hypothyroidism). She also cross trained with the elliptical and Airdyne bike. She trained and raced based on perceived exertion rather than with a heart-rate monitor (despite using one prior to her pregnancy) and delivered a healthy baby girl, Maya, at 40 weeks.

In terms of racing, at 9.5 weeks pregnant, she ran the 2014 Cimarron 50k at an average altitude of 8,400 feet in 4:41:55 and won. Then she finished second female in 12:01:50 at the 2014 Gunnison 100k at four months pregnant. Finally, she took second female at the 2014 Waugoshance Trail Marathon in a time of 3:46 at five months pregnant.

iRunFar: Tell us about the Gunnison 100k. Were there any complications or adverse effects from that race?

Michele Yates: No, although I monitored myself closely and was certain not to overheat, hydrate very often, eat often, and ultimately took my time.

iRunFar: Did you check you temperature? Did you drink based on thirst?

Yates: I didn’t monitor basal temperature, just went by feel and took extra precaution with applying cooling rags.

iRunFar: How far along were you in your pregnancy when you stopped running altogether?

Yates: I didn’t. I actually even ran a 24-minute-flat 5k three days before I delivered.

iRunFar: Were there any complications with your pregnancy or delivery?

Yates: The labor was initially slow, so an epidural was recommended and I had to be induced but then I gave birth within 30 minutes!

iRunFar: Did you experience any negative consequences of running during or immediately following your pregnancy? If so, what?

Yates: Yes and no. I decided to take the week off from running or strength training after her birth. The following week, I added in some strength training with cross training like elliptical or bike and walking, then elliptical with a little harder efforts for a few more weeks. By one month out, I was running again and the only thing I experienced was lack of bladder control and leakage. When I got pregnant, I found out I had thyroid disease inherited from my father. I was started on levothyroxine (to treat hypothyroidism) right away, and was continued on it throughout the rest of the year.

iRunFar: Did you have any running-related long-term injuries during or following your pregnancy? If so, what?

Yates: No. However, I found out later that my hips did not develop properly when I was a child so I’m sure that didn’t help my cartilage with running with extra weight.

iRunFar: What is the exact condition called that you have with your hips?

Yates: Femoralacetabular impingement, labrum tears, cysts, severe arthritis in hips, and pelvis cysts on pubic bone.

iRunFar: How old is Maya now and is she healthy?

Yates: Three, very healthy, smart, and actually scores above average for her age level in most things.

iRunFar: What was the most positive and the most negative impact of running on your pregnancy (on either you or your child), in your opinion?

Yates: Positive, kept me healthy, her healthy, and happy. Negative, possibly the hips, but I don’t think that would have been an issue if my bones grew the right way in the first place.

iRunFar: Did you see an improvement or slowing in your race times in the years following your pregnancy?

Yates: Struggled with thyroid disease, then the hip surgeries, and just recently within the last month a miscarriage due to thyroid disease.

iRunFar: I am so sorry about your loss, Michele. How far along were you?

Yates: Only five to six weeks, but it still stung.

iRunFar: What was your favorite resource about running/exercising in pregnancy?

Yates: Exercising Through Your Pregnancy by James Clapp. And I did my homework, asked all the elite-runner ladies I knew for their experience as well as posted on running groups via Facebook.

Alicia Vargo

Alicia Vargo has a stout racing resume as she’s a two-time NCAA 10,000-meter champion with a 15:25 5,000-meter PR and a 32:19 10,000-meter PR, the latter time being a former NCAA record for the distance from when she set it in 2004 until 2010. Her top finishes in trail ultrarunning have been a sixth place at the 2014 TNF 50 Mile and a fourth place at the 2015 Transvulcania Ultramarathon.

She gave birth to a healthy baby girl, Skylar, four months ago and set a new fastest known time in the Grand Canyon’s Rim-to-Rim of 3 hours, 19 minutes, and 23 seconds on November 8, ahead of Ida Nilsson and Kristi Knecht. She finished nearly 30 minutes under the previous record, set by Bethany Lewis in 2011. As she says, “It was awesome to try to run a fast time through the canyon, but that was really only part of the experience. After years of struggling… in my personal life and with health issues, I don’t take opportunities like this for granted.”

Alicia Vargo, her husband, Chris Vargo, and their baby girl, Skylar, at the Grand Canyon. Photo: Andrew Vargo Photography

iRunFar: Alicia, can you tell us a bit about your experience running during pregnancy? What is the furthest distance you raced/ran at one time during your pregnancy?

Alicia Vargo: The longest I ran while pregnant was three hours and with 5,000 feet of elevation gain down to the Colorado River and back in the Grand Canyon!

iRunFar: How far along in your pregnancy were you when you ran this?

Vargo: Twenty-six weeks.

iRunFar: Were there any complications or adverse effects from this run?

Vargo: I didn’t have any adverse side effects from this long run or comparable long runs outside of noticing that it took me a bit longer to recover from the effort than it normally would. I just felt I needed extra sleep for a couple of days following any longer effort.

iRunFar: What was your training like during your pregnancy?

Vargo: First trimester: Six to 10 hours a week of running and skiing. There were a of couple weeks in there where I only felt good enough for two- or three-mile runs. This time was miserable. Mono mixed with horrible nausea and fatigue. Uphill skiing felt way better than running so I mostly did this as well as a lot of backcountry skiing.

Second trimester: Six to 13 hours a week, around 50 miles/week of skiing and running. The skiing was all uphill-type skiing. I was averaging around 2,000 to 4,000 feet of gain a day up to 12,000 feet. This for some reason felt better than a flat four-mile run at lower elevations. I also got in some bigger six-plus-hour backcountry days. The only negative effect I had was getting some contractions immediately after, likely because I was getting too dehydrated. I had a broken wrist during this time so had to dial back. Still felt pretty rough.

iRunFar: Oh, bummer! How did you break your wrist? How far along were you?

Vargo: I was around 23 weeks and it happened during a backcountry ski. We skinned up to 12,000 feet and then skied this really beautiful line… To exit we had to ski through this flat and boring area that had a lot of downed trees and stumps from a recent fire. Anyway, I hit a burned stump that was barely covered with snow and launched a bit, hit another stump with the tips of my skis and then punched a rock while trying to stop myself from falling. It was a super-stupid, slow-motion kind of ordeal… I had to get surgery immediately. I thought my doctors and surgeons would hassle me for being out backcountry skiing while pregnant but they all just wanted to know what line I was skiing and how the snow was.

Third trimester: Eight to 12 hours a week, around around 50 to 70 miles/week of all running.

I still battled really bad nausea, but I think the effects of mono started to wear off and I felt so much better than the previous two trimesters. I was running a lot more and way faster than the beginning of pregnancy.

Most of my training during this time is on Strava but I didn’t log everything (especially the longer ski and run sessions) just because I got some negative feedback from family, friends, and random strangers. It was just easier to not make that stuff public because I knew I was being cautious and didn’t want to defend myself. I felt like my activity level was something for my husband and myself to decide. I backed off and rested when it didn’t feel right and I did more when it felt like it was okay.

I did wear a heart-rate monitor through most of my pregnancy. I started wearing it because of my mono and not wanting to push through that fatigue in conjunction with being pregnant. I tried to average somewhere between 140 to 150, which is much higher than my normal heart rate. I found that the mono increased my resting heart race as well as my easy-effort heart rate, as did pregnancy. I just found that particular heart rates corresponded with an ‘easy’ effort and didn’t leave me feeling extra tired after the run or ski.

[Author’s Note: Resting and exercising heart-rate increase during the first trimester of pregnancy is due to blood-vessel relaxation, so this may have been Alicia’s natural physiologic response and unrelated or only partially related to her mono infection. By the mid-point in pregnancy, heart rate usually corresponds to non-pregnant heart rate and then resting and exercising heart rate slow from the midpoint on all the way to delivery.]

iRunFar: Did you enter any races during your pregnancy?

Vargo: I did not race throughout my pregnancy for a couple of reasons. The main reason is because I started pregnancy with mono and just felt horrible. I ran very little during the first trimester because of this double whammy of fatigue and sickness. The thought of racing sounded miserable and I didn’t want to force it. I did start to feel a bit better toward the end of the second trimester and throughout the third trimester but I was still really battling all-day nausea and fatigue. Racing in that state just didn’t sound appealing. I much preferred getting outside every day and if it was a better-feeling day, then I would push it a little. If I felt worse than normal, I would dial things back. I really liked having the freedom of taking things day by day. My body varied a lot day to day and I could not predict the pattern. I also had pretty bad insomnia the third trimester because my little girl would literally kick me all night and keep me up!

Many of these reasons I didn’t race were physical but I also mentally knew I would have a hard time competing with just a fraction of my normal strength and speed. I preferred to just enjoy getting outside and adventuring with my husband and friends. I found that this approach kept me in pretty good shape, was low stress, and had me really eager to get back to racing after I had Skylar.

iRunFar: Did you stop running altogether at any point?

Vargo: I stopped running at 37 weeks and replaced running with steep uphill, high-altitude hiking for the remaining week of pregnancy.

iRunFar: How far along were you when you delivered?

Vargo: Thirty-eight weeks.

iRunFar: Were there any complications with your pregnancy or delivery?

Vargo: I didn’t have any complications during pregnancy or delivery other than it was ridiculously painful! :) I had mono when I got pregnant but that was totally unrelated to pregnancy.

iRunFar: Did you experience any negative consequences of running during or immediately following your pregnancy?

Vargo: No, not at all.

iRunFar: Did you have any running-related long-term injuries during or following your pregnancy? If so, what?

Vargo: The only issue that I had was my ankle ligaments. I kept rolling and spraining my ankles and the more I rolled them, the easier it was to continue to do so. I continued running on rocky and steep trails throughout my pregnancy so I knew that I would be at risk for this with the increase in the hormone relaxin. The sprains never kept me from not running for more than a day, but it was definitely an ongoing issue. I had some pretty bad snaps that caused me to just crumble to the ground and I still feel like my ankle ligaments aren’t at full strength.

Outside of that, my adductor, psoas, and oblique on one side of my body got really tight but also really weak. I had a few therapy sessions for these areas and it eventually resolved. This issue started around 35 weeks when I had some really strong contractions for several hours. I went into labor and delivery and ended up being fine but those areas got pretty fired up during the contractions and then just stayed that way with training until a few weeks after I delivered.

[Author’s Note: While there has been shown to be an increase in peripheral-joint laxity in pregnancy, the role of relaxin in this is not clear and studies have had conflicting results.]

iRunFar: Did you see an improvement or slowing in your race times following your pregnancy?

Vargo: To be determined!

[Author’s Note: Given her R2R FKT, finishing faster than Ida Nilsson, I already have an opinion!]

iRunFar: How old is Skylar and is she healthy?

Vargo: Skylar is four months old and very healthy! Her birth weight was below average (4 pounds, 4 ounces) but she quickly gained weight and was really healthy otherwise.

[Author’s Note: Normal birth weight at term is 5.5 to 8.8 pounds (2,500 to 4,000 grams). Please see the section above on altitude and birth weight. Given Alicia lived at 7,300 feet and skied up to 11,000 to 12,000 feet every day in the winter and spring, Skylar’s birthweight was not too surprising. Also, as stated above, exercise in pregnancy (with adequate caloric intake) actually promotes appropriate birth weight. Infection with Ebstein Barr Virus (which causes ‘Mono’) during pregnancy has also been shown to slightly shorten length of gestation and lead to a correspondingly lower weight at birth (Eskild, 2005).]

iRunFar: What was the most positive and the most negative impact of running on your pregnancy (on either you or your child), in your opinion?

Vargo: Most positive: I felt extremely nauseous and sick the entire nine months of pregnancy except when I ran or skied. Running literally was the only medication that would temporarily take away my nausea. I savored that hour or so every day that I didn’t feel ill. Running made me feel better in general, physically and mentally. The days I didn’t get outside and move seemed to spiral into just feeling sick, sicker, vomiting, and having a miserable day.

Most negative: Doubt. Not knowing how much running and physical effort was appropriate made me feel pretty stressed about running sometimes. I knew deep down that it was good for me and not detrimental for my baby, but the lack of information on endurance training through pregnancy always made me feel a little bit uncertain that I might be doing something that wasn’t healthy. My baby’s weight was always on the low side and I didn’t know if running was taking away resources that she needed to grow more. This ended up not being the case. She was just tiny but totally healthy. However, the stress of daily deciding if I should or shouldn’t run was pretty negative. Next time around, I will run knowing that it is good and healthy for both me and my baby and probably be more comfortable with sometimes putting in a bit harder effort. I purposefully always kept my heart rate and effort very low but I think I was too far on the side of caution in this regard.

iRunFar: Finally, what was your favorite resource about running/training during pregnancy?

Vargo: The best resource for training guidelines that I found when I was pregnant was a chapter in Stacy Sims book ROAR. It was just one chapter but made me feel more confident in the decisions I was making and trusting myself to make decisions throughout the nine months and the recovery process.

[Author’s Note: My favorite reference for running and exercising during pregnancy was (for those who read Danish) the book Graviditet & Motion by Bente Klarlund Pedersen.]

Take-Home Points

- Running during pregnancy is healthy. It is associated with better health outcomes for the mother, decreased risk of pregnancy complications, and positive neurological adaptations in the child.

- Exercising at greater than 90% of maximum heart rate is not advised during pregnancy. For more competitive athletes who wish to push themselves in competition or training, a heart-rate monitor may be advisable.

- Avoid exercising at greater than 85% maximum heart rate at gestational days six to nine at the time of embryronic implantation and avoid overheating (greater than 39°C) at days 21 to 28 to protect the formation or the neural tube.

- You will need to pee a lot. Plan accordingly.

- Training at altitudes higher than 6,000 feet should be done after two to three days of acclimation. Living or spending a lot of time at altitude may make your baby smaller.

- Low-back and pelvic pain is common in pregnancy. It is advisable for runners and non-runners alike to develop a regular core and hip-girdle strength-training program to help prevent pregnancy-related low-back and pelvic pain. Some runners may find a sacroiliac belt helpful to run with later in pregnancy.

- Avoid running in areas where you are more than an hour from medical care in case you fall or start to develop pregnancy complications. Similarly avoid steep, especially technical terrain that puts you at high risk of falling.

- If you are a runner and get pregnant, find a doctor or midwife who is a runner and/or promotes and is educated about the myriad benefits of exercise during pregnancy. An individualized exercise program should be developed according to your comfort level and sports and exercise background. Also, find mentors who have run through their pregnancies with whom you can share your concerns.

- Finally, have fun. Pregnancy is a unique experience that occupies just a short duration of women’s lives. You should prioritize doing the things that keep you healthy and happy and you and your baby will both benefit from this.

Call for Comments

- Are you aware of any ongoing studies looking at running during pregnancy that interested women can sign up for?

- What do you think the biggest misconceptions are about running during pregnancy?

- What are your biggest concerns?

- Do you have stories to tell from running during your pregnancy?

- Feel free to contact author Tracy at [email protected] with any follow-up you have.

References

- Ammon Avalos L., Galindo C., Li D.-K. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:417–423

- Artal R, Fortunato V, Welton A, et al. A comparison of cardiopulmonary adaptations to exercise in pregnancy at sea level and altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172(Pt 1):1170–8; discussion 78-80.

- Artal R, Hopkins S. Exercise. Clin Update Womens Health Care 2013; 12:1.

- Artal R, Tomlinson T. Exercise: The logical intervention for diabetes in pregnancy. In: Diabetes in Pregnancy, Langer O (Ed), People’s Medical Publishing House, 2015. p.189.

- Aune D, Saugstad OD, Henriksen T, Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2014; 25:331.

- Bigelow C & Stone. Bedrest in Pregnancy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011 Mar-Apr;78(2):291-302.

- Blackburn, ST. Maternal, fetal, & neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective. Book. English. 3rd ed. All formats and editions (2). Published Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders, 2007.

- Bonzini M, Coggon D, Palmer KT. Risk of prematurity, low birthweight and pre-eclampsia in relation to working hours and physical activities: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:228–43.

- Bø K, Backe-Hansen KL. Do elite athletes experience low back, pelvic girdle and pelvic floor complaints during and after pregnancy? Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17:480–7.

- Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, et al Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 4—Recommendations for future research Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1724-1726.

- Bullard JA. Exercise and Pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 1981 Jun; 27: 977–982.

- Chambers CD. Risks of hyperthermia associated with hot tub or spa use by pregnant women. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2006;76:569–73.

- Clapp JF. Acute exercise stress in the pregnant ewe. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Feb 15;136(4):489-94.Clapp JF, Cram C. E. Exercising Through Your Pregnancy. (2nd ed.) Omaha, NE: Addicus Books.

- Clapp JF III., Capeless E. The VO2max of recreational athletes before and after pregnancy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991;23:1128–33.

- de Oliveria Melo AS, Silva JL, Tavares JS, et al. Effect of a physical exercise program during pregnancy on uteroplacental and fetal blood flow and fetal growth: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2012; 120:302.

- Dittmer DK, Teasell R. Complications of bed rest: part 1: musculoskeletal and cardiovascular complications. Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:1428–1437.

- Elliott-Sale KJ, Barnett CT, Sale C. Exercise interventions for weight management during pregnancy and up to 1 year postpartum among normal weight, overweight and obese women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015; 49:1336.

- Entin PL, Coffin L. Physiological basis for recommendations regarding exercise during pregnancy at high altitude. High Alt Med Biol 2004;5:321–34.

- Erdelyi GJ. Gynecology survey of female athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1962;2:174-179.

- Eskild, A., Bruu, A.-L., Stray-Pedersen, B. and Jenum, P. (2005), Epstein–Barr virus infection during pregnancy and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 112: 1620–1624.

- Gavard JA, Artal R. Effect of exercise on pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2008; 51:467.

- Hegaard HK, Hedegaard M, Damm P, et al. Leisure time physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:180–185.

- Heggard HK, Ersbøll AS, Damm P. Exercise in Pregnancy: First Trimester Risks.Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 59(3):559–567, SEP 2016

- Hjollund NH, Jensen TK, Bonde JP, et al. Spontaneous abortion and physical strain around implantation: a follow-up study of first-pregnancy planners. Epidemiology 2000;11:18–23.

- Hunt KJ, Alanis MC, Johnson ER, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy weight and gestational weight gain and their association with birthweight with a focus on racial differences. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:85–94

- Jensen GM, Moore LG. The effect of high altitude and other risk factors on birthweight: independent or interactive effects? American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(6):1003-1007.

- Jokl E. Some clinical data on women’s athletics. J Assoc Physical and Mental Rehabilitation. 1956;10:48.

- Juhl M, Olsen J, Andersen PK, et al. Physical exercise during pregnancy and fetal growth measures: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:63.el-63.e8.

- Juhl M, Andersen PK, Olsen J, et al. Physical exercise during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:859-866.

- Kardel KR. Effects of intense training during and after pregnancy in top-level athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2005;15:79–86.

- Kluge J, Hall D, Louw Q, et al. Specific exercises to treat pregnancy-related low back pain in a South African population. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011; 113:187.

- Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; :CD001139.

- McCrory MA, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Molé PA, et al. Randomized trial of the short-term effects of dieting compared with dieting plus aerobic exercise on lactation performance. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69:959.

- Milunsky A, Ulcickas M, Rothman KJ, Willett W, Jick SS, Jick H. Maternal heat exposure and neural tube defects. JAMA; 1992 Aug 19;268(7):882-5.

- Moore, K. The Best Norse in the Long Run. Sports Illustrated. Oct. 27, 1986. https://www.si.com/vault/1986/10/27/114242/the-best-norse-in-the-long-run-ingrid-kristiansen-of-norway-a-skier-turned-runner-is-the-fastest-woman-in-the-world-over-5000-meters-10000-meters-and-in-the-marathon

- Mottola MF, Davenport MH, Brun CR, et al. VO2peak prediction and exercise prescription for pregnant women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:1389–95.

- Muktabhant B, Lumbiganon P, Ngamjarus C, Dowswell T. Interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; :CD007145.

- Owe KM, Bjelland EK, Stuge B, et al. Exercise level before pregnancy and engaging in high-impact sports reduce the risk of pelvic girdle pain: a population-based cohort study of 39 184 women. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50:817.

- Perales M, Calabria I, Lopez C, et al. Regular Exercise Throughout Pregnancy Is Associated With a Shorter First Stage of Labor. Am J Health Promot 2016; 30:149.

- Perales M, Santos-Lozano A, Sanchis-Gomar F, et al. Maternal Cardiac Adaptations to a Physical Exercise Program during Pregnancy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016; 48:896.

- Poyatos-León R, García-Hermoso A, Sanabria-Martínez G, et al. Effects of exercise during pregnancy on mode of delivery: a meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015; 94:1039.

- Price BB, Amini SB, Kappeler K. Exercise in pregnancy: effect on fitness and obstetric outcomes-a randomized trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012; 44:2263.

- Salvesen KA, Hem E, Sundgot-Borgen J. Fetal wellbeing may be compromised during strenuous exercise among pregnant elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:279–83.

- Soultanakis HN, Artal R, Wiswell RA. Prolonged exercise in pregnancy: glucose homeostasis, ventilatory and cardiovascular responses. Semin Perinatol 1996;20:315–27.

- Salvesen KA, Hem E, Sundgot-Borgen J. Fetal wellbeing may be compromised during strenuous exercise among pregnant elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:279–83.

- Salvesen KÅ, Stafne SN, Eggebø TM, Mørkved S. Does regular exercise in pregnancy influence duration of labor? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014; 93:73.

- Szymanski LM, Satin AJ. Strenuous exercise during pregnancy: is there a limit? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:179.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.021CrossRefPubMed

- Tanner CE, Atalay E, Solmaz U, et al. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2015; 16(4): 231–236.

- Tenforde, A., Toth, K., Langen, E. Fredericson E, Sainani L. “Running Habits of Competitive Runners During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding”. Sports Health. March/Apr 2015, 7:2, (172-176)

- Tinloy J, Chuang CH, Zhu J, et al. Exercise during pregnancy and risk of late preterm birth, cesarean delivery, and hospitalizations. Womens Health Issues 2014; 24:e99.

- Wallace JP, Rabin J. The concentration of lactic acid in breast milk following maximal exercise. Int J Sports Med 1991; 12:328.

- Wiebe HW, Boule NG, Chari R, et al. The effect of supervised prenatal exercise on fetal growth: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 125:1185-1194.

- Zavorsky GS & Longo LD. Viewpoint: Are there valid concerns for completing a marathon at 39 weeks of pregnancy? JAP. 2012; 113(7): 1162-1165.