As a fan of many endurance sports, I took pause earlier this winter when the entire Norwegian cross-country ski team sat out an early season race due to extreme cold. The Norwegian team was not worried about frostbite, but rather the short- and long-term consequences of extremely cold air on their athletes’ respiratory systems. They said that they wouldn’t be taking such risks so close to the Winter Olympics.

The International Ski Federation currently follows a very specific set of rules that dictate how cold is too cold for ski racing, saying races must be delayed or canceled if the coldest point of the course is colder than -4 degrees Fahrenheit (F)/-20 degrees Celsius (C).

On that day in Finland, where the race took place, the temperatures were close to, but not below, the legal racing limit. However, current research shows that respiratory system damage can occur at temperatures warmer than -4F (-20 ).

While cold-weather concerns are commonly considered in winter sport circles, running is a year-round sport, and many of us spend significant time exposed to a wide range of temperatures — including extreme cold. Cold temperatures alter the way we dress: we use layers to cover exposed skin and stay warm, and we employ technical materials to keep dry, but these elements only cover our external bases.

What about the inside of our bodies? Should we worry about the cold affecting our lungs? Is there risk in slogging out runs as the temperature drops? How cold is too cold for doing intervals, or exercising outside at all?

In this article, we address these questions and look at the short- and long-term risks of cold exposure to your respiratory system, and what you can do to exercise safely year-round.

While this article focuses on cold weather and our respiratory system, you might want to also read our previous in-depth article on non-asthma breathing problems in endurance running.

Devon Yanko showing off some good strategies for protecting your lungs while running in the cold. Photo: Devon Yanko

Running in Extremely Cold Temperatures Can Be Very Dangerous

There is currently a general consensus among the scientific community that exercising in temperatures of 5 F (-15 C) and below requires special considerations in order to protect your respiratory system, including making adjustments to training duration and intensity, and covering your mouth with a buff, AirTrim mask, or other covering in order to protect your lungs (1).

One of the main reasons for this is that essentially all cold air is very dry air (1). For example, air that is -4 F (-20 C) holds 99% less total water content than air that is 32 F (0 C). Inhaling very cold and dry air presents as an acute physiological stressor to the surfaces of your airway (1). This is because your airway is lined with a liquid surface and when you breathe, this liquid naturally evaporates a little. If you breathe cold, dry air hard or a lot, this liquid evaporates faster than your body can cope, causing a cascade of negative effects that we’ll talk about in a little more detail below.

One of the foremost researchers in this area is Dr. Michael Kennedy, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. In a recent article, Kennedy cautioned, “If it’s a really cold day in February, a high-intensity run or ski could change your life.”

Unlike most of the other structures of our body which get stronger and bigger in response to the stresses of endurance running, such as our hearts or leg muscles, our lungs can respond to significant stress by remodeling in a way that diminishes our lung function over time (2).

Airway Dysfunction in Athletes: What Is Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction?

Chronic airway dysfunction in athletes is called exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB).

As previously described, when you inspire large volumes of cold, dry air during a workout or competition, this results in water loss from the liquid surface that lines your airways (3). As that liquid surface dries, it changes the concentration of the surface of the airways.

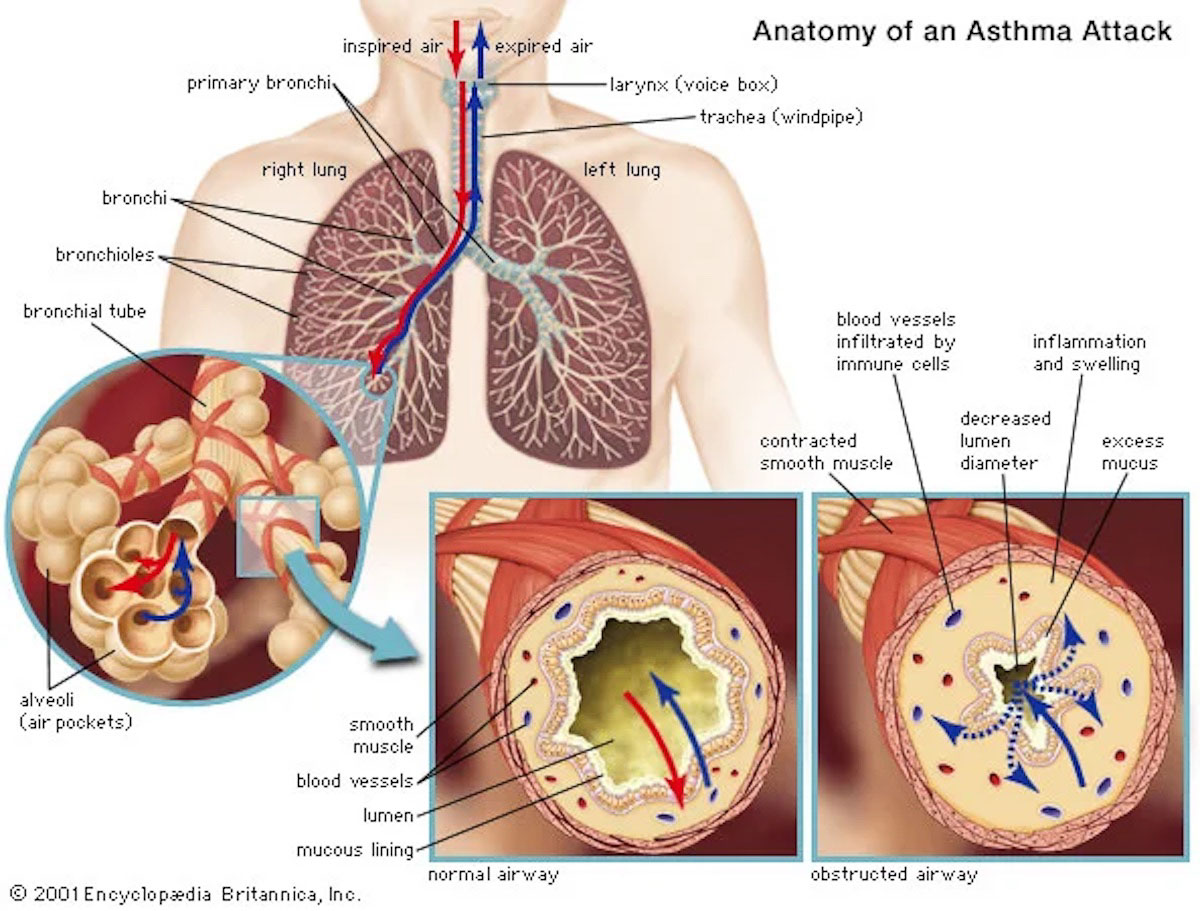

Known as an osmotic shift, this contracts and shrinks the cells that make up the lining of your bronchioles, the smaller tubes that carry air into your alveoli within your lungs. What happens next is the release of a number of inflammatory mediators, like histamine, which ultimately causes the smooth muscle of your airway to constrict. Further, mucus and swelling build up in the airway. All of this together can lead to long-term, permanent airway remodeling.

On the left is a normal airway with an unobstructed center, called the lumen. On the right is an obstructed airway, where a constricted bronchial tube decreases the diameter of the lumen, making it hard for air to reach the alveoli where gases are exchanged with the bloodstream. Image: Britannica.com/science/asthma

What’s even scarier about airway inflammation and limitation, is that they appear to be progressive over a lifetime in some endurance athletes, with 90% of the asthmatic population and 20% of the general population developing EIB (4). According to Dr. Michael Kennedy, those numbers are probably understated.

The progressive nature of EIB is possibly the biggest issue for athletes, with repeated exposure making things worse over time (5). Alongside this permanent remodeling, airways also become more reactive over time, meaning that you become more sensitive to the same irritants.

Airway remodeling and chronic hyper-reactivity ultimately lead to a ventilatory limitation during performance (5). While short-term consequences include wheezing and post-exercise coughing, long-term consequences to chronic extreme cold exposure have a high probability of causing long-lasting problems which can progress to EIB, ultimately requiring medical intervention.

What Should Athletes Do When It’s Really Cold Outside?

Here’s some practical advice and a set of guidelines you can utilize when the temperatures dip.

We know that the temperature limitation of -4 F (-20 C) used by the International Ski Federation is more about protecting athletes from frostbite and hypothermia, and is an important piece of guidance to follow for protecting our body’s external structures. Right now, research suggests that 5 F (-15 C) is a good minimum threshold for protecting the respiratory system from damage caused by competition and intense training in extreme cold, and one that I think we runners should follow.

There seems to be a slight decline in post-hard-exercise ventilatory function testing between 14 F (-10 C) and 5 F (-15 C), but not to the same extreme seen at temperatures below 5 F (-15 C). I would caution athletes who know cold-weather exercise provokes breathing changes for them, or if they develop post-exercise coughing, to exercise with caution at these temperatures.

Once temperatures fall below 5 F (-15 C), move exercise inside if possible. If that’s not possible, take action to protect your airway while running outdoors. First, keep outdoor exercise easy to allow more time for your lungs to warm and humidify the air (2). Basically, if you are running easily enough that you can breathe through your nose, that gives your lungs a little break.

Also, because we know that the main issue for our lungs is that cold air is dry air, we can also use different strategies to limit the drying out of our airway surfaces at these very cold temperatures. The first way to do this is to cover your mouth with a heat and moisture exchange device to pre-warm and humidify the air you are inhaling (3).

This can be as simple as a buff, and there are also masks like the AirTrim mask developed for the cross-country skiing market that are constructed to allow easier breathing and can be fitted with various filters. One other option is to utilize an indoor warmup of 15 to 20 minutes before training outside, which helps dilate the bronchioles and reduces the effects of cold air once you get out the door (2).

Sometimes exercising at a lower intensity is a good solution to avoid damaging your sensitive airway tissues when it’s very cold. Photo: Alex Potter

Takeaways for Running in the Extreme Cold

- Cold air is dry air, and lungs don’t like this. Air that is at -4 F (-20 C) contains 99% less water content than air that is 32 F (0 C) (1). While breathing in other irritants can also stress the lungs, it’s important to remember that cold air, even when it’s pristine, can acutely impact your short-term and long-term lung health.

- Adjust your training in extreme cold. Running in negative temperatures doesn’t prove you’re the toughest runner on the block. Adjust your training to run in the warmest part of a cold winter day, cut your run short, cut intensity, move your exercise inside, or don’t run at all. One run or hard session in 5 F (-15 C) or below temperatures isn’t going to make or break your race buildup, but it could permanently remodel your lungs.

- Move your warmup inside. One way to help your lungs stave off the impact of inhaling cold air on the run is to start your run inside. Spending 15 to 20 minutes warming up not only your body but your lungs indoors before heading outside helps to dilate your lungs and lessen the impact of inhaling cold air.

- Mask up when training in extreme cold outdoors. Help to warm and humidify the air you are breathing by running with a mask designed for cold-weather use or a buff over your mouth. Buffs are effective, but they have a higher mechanical resistance for breathing than specialty masks and also have a tendency to get wet and freeze over, rendering it difficult to breathe or warm the air effectively.

Call for Comments

- What’s the coldest weather you’ve ever run in?

- Do you tend to move inside if it’s too chilly, or face the elements at all costs?

References

- Kennedy, M. D., & Faulhaber, M. (2018). Respiratory function and symptoms post cold air exercise in female high and low ventilation sport athletes. Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Research, 10(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2018.10.1.43

- Brown, M. 2020. Exercising in very cold weather could harm lungs over time, researcher cautions.Ualberta.ca. February 1st, 2022. https://www.ualberta.ca/folio/2020/01/exercising-in-very-cold-weather-could-harm-lungs-over-time-researcher-cautions.html

- Gatterer, H.; Dünnwald, T.; Turner, R.; Csapo, R.; Schobersberger, W.; Burtscher, M.; Faulhaber, M.; Kennedy, M.D. Practicing Sport in Cold Environments: Practical Recommendations to Improve Sport Performance and Reduce Negative Health Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189700

- Kippelen, P., Fitch, K., Anderson, S., Bougault, V., Boulet, L., Rundell, K., Malcolm, S., & Mckenzie, D. (2012). Respiratory health of elite athletes- preventing airway injury: A

critical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 471-476. - Sheel, A., Macnutt, M., & Querido, J. (2010). The pulmonary system during exercise in hypoxia and the cold. Experimental Physiology, 422-430.