[Editor’s Note: Welcome to iRunFar’s Community Voices column! This month, we are honored to share an excerpt from the book Running Home by longtime journalist and 2018 Leadville Trail 100 Mile champion Katie Arnold. Running Home is a memoir about how life and running interweave in sometimes simple and other times profound ways. In this column each month, we are showcasing the work of a writer, visual artist, or other creative type from within our global trail running and ultrarunning community. Our goal is to tell stories about our sport in creative and innovative ways. Read more about the concept in our launch article. We invite you to submit your work for consideration!]

I became a runner by accident. It was April 1979, and I was seven. My sister, Meg, and I were visiting Dad at his farm, as we always did over Easter break. Spring was the best time of year in Virginia: the cherry blossoms were in bloom, and the grass and leaves were greener than they were in New Jersey, where we lived with our mother. Easter was Dad’s holiday with us, just like Thanksgiving and New Year’s and the last few weeks of August. Often when we were with him, I had the uneasy feeling that this was not enough time and also too much. Dad was always trying to think up clever things to do with us.

I became a runner by accident. It was April 1979, and I was seven. My sister, Meg, and I were visiting Dad at his farm, as we always did over Easter break. Spring was the best time of year in Virginia: the cherry blossoms were in bloom, and the grass and leaves were greener than they were in New Jersey, where we lived with our mother. Easter was Dad’s holiday with us, just like Thanksgiving and New Year’s and the last few weeks of August. Often when we were with him, I had the uneasy feeling that this was not enough time and also too much. Dad was always trying to think up clever things to do with us.

Now he had an idea. “What do you think about running a race?” he announced at breakfast. “Six miles, from Flint Hill to Little Washington?”

“How far?” I asked, between bites of peanut butter toast.

“Six miles,” he repeated. “On the Fodderstack Road.”

”I knew the road he was talking about. It was famous in our family for its short, steep hills—tummy-funnies, we called them whenever Dad intentionally revved his rust-colored diesel Rabbit over the small rises, sending our stomachs into our throats, as if we were hurtling down a roller coaster.

Six miles. The distance was so audacious that it meant absolutely nothing to me. I had never run a race, never a single mile, let alone six, all in a row. Dad might as well have been suggesting we run home to New Jersey.

Dad smiled, his mouth curling into a sly, crinkled grin. It was, like so many of his ideas, a lark. He was half daring us to say yes but not really believing we would.

“Running?” I said again. Never in my life had I seen my father run or heard him talk about running. He liked hiking and camping and riding his bicycle along country roads, exploring. This was often what we did when we were together, rambling around with no apparent destination, up and down trails in the woods, in our red Keds, bashing at brambles with our bare arms, dying of boredom and fatigue but not wanting to quit, because this was the only time we got with Dad and we didn’t want to waste it.

Dad nodded. He’d thought it all out. “You two can run the race, and I’ll be waiting in Little Washington, taking pictures.”

This made complete sense to me. Dad was a National Geographic photographer. Just the thought of this gave me a little shiver of pride. The kids I knew in New Jersey had banker dads or lawyer dads or dads who ran Chinese restaurants, but my dad walked around with cameras dangling from his neck and wore a mesh khaki vest and got his pictures on the cover of the most famous magazine in the world. In my eyes, this was a grand and noble pursuit that bestowed upon him, and, by extension, me, the faint glow of celebrity. Picture-making was important work, and it trumped everything, even the craziest of things, like running six miles without any training or parental supervision.

Dad assured us that other kids would be running the race, too, and lots of grown- ups, some of whom were his friends, so even though he wouldn’t be with us, we wouldn’t be alone. If we got tired, we could always walk, and, he chuckled, he’d be there to capture our triumphant finish on film. Those were his actual words: triumphant finish.

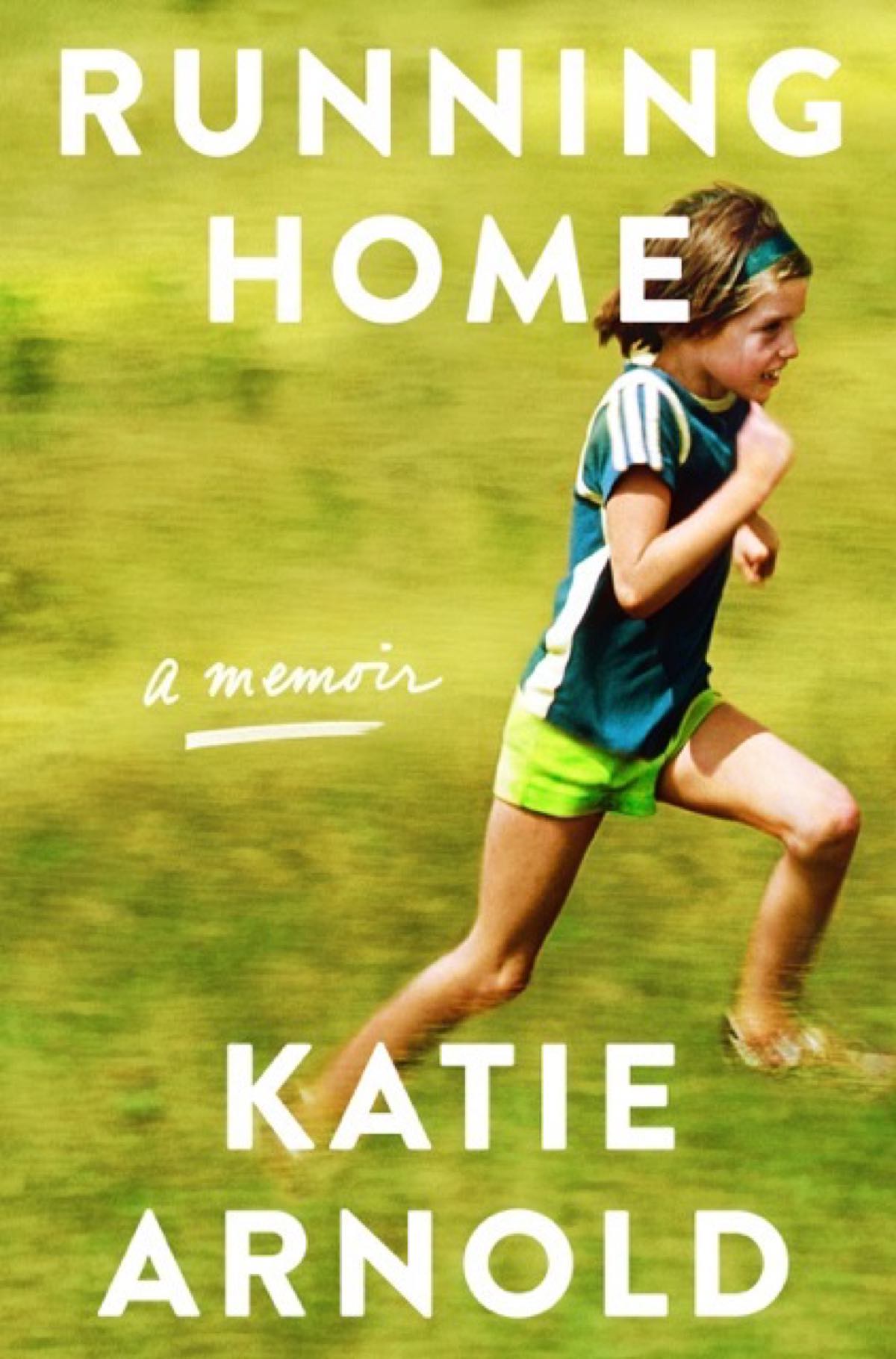

I was a stringy second grader with a Dorothy Hamill haircut and perpetually skinned knees. For the past three months, the bathroom scale hadn’t budged from forty-nine pounds. Mom joked that maybe I would always be forty-nine pounds, and part of me worried that she was right. Meg had Princess Di cheekbones and skinny supermodel legs and was on her way to becoming six feet tall. She might actually have a legitimate chance of finishing the race, but I was the long shot, the underdog, the scrappy kid sister desperate for Dad’s attention.

“Sure,” I said, tugging my mouth into a grin to match my father’s. “Okay.”

***

Meg and I made an unlikely, woebegone pair on the starting line of the second annual Fodderstack 10K Classic. We wore holey Tretorn tennis shoes that, much to our mother’s chagrin, were fashion-forward in 1979; ankle socks with purple pom-poms; and terry-towel gym shorts destined to become soggy with sweat, like clammy kitchen sponges, at the slightest exertion. The collar on my raspberry-pink Izod shirt was turned up, and I’d stuck a ribbon barrette in my hair to keep my bangs out of my eyes.

The instant the gun went off, we lit out hopefully for Little Washington, sneakers slapping, limbs flailing. Two-tenths of a mile in, where the course turned right onto the Fodderstack Road, we were decisively dropped off the back of the pack. We inched forward in a bumbling, ill-advised combination of running, jogging, walking, limping, and staggering. The effort engulfed us—Meg and I locked in our own private circle of hell, yet too dwarfed by the distance to stray far from each other. It seemed desperately improbable that we would ever make it, and yet how could we quit? We had no choice but to push on. Few words passed our lips, just the occasional pained grunting.

The course was pretty, passing hundred-year-old brick farm houses with high hedges and stone walls. Dogwoods bloomed pink in the meadows. The road rolled up and over short climbs and down the other side. Every couple of miles, farmers in denim overalls stood at the roadside holding out Styrofoam cups of water from wobbly card tables. Meg and I stopped at all of them, drinking as though we’d been lost in the desert for all of eternity. At about the three-mile mark, the course ascended a long hill. Dad had actually referred to it in jest as a “mountain,” and from the bottom, staring up at the long squiggle of blacktop disappearing beneath a canopy of oak and maple trees, it looked as menacing as any I’d ever seen. I leaned into the slope, trying to will my legs to move, trying not to cry. Beside me on the road, Meg attacked the climb. Her gangly legs were so long that for every step she took, I had to take two just to keep up. I had to keep up. Somewhere in the distance, Dad was waiting to capture the moment on film for posterity.

Dad wore his camera everywhere he went, like an extra appendage, as familiar to me as his thick horn-rimmed glasses and his wavy black hair that crept back slightly from his high forehead. Slung around his neck, the Nikon was part of his dress code. He never took just one picture—never. “One more shot,” he’d murmur as the shutter went click, click and Meg and I held our positions, eyeballs rolling back in our heads with exasperation. “Okay, just one more, one more.” Behind the lens, Dad seemed to disappear and become the camera itself.

In film, there are two sides to every picture. Negatives render dark subjects light and light subjects dark: reality inverted. But the positive image is not infallible, either. To tell the truth of something, you need both light and dark, sun and shadow, transparency and secrecy, things exposed and others withheld. If you are patient and pay attention, these details might begin to arrange themselves into a recognizable shape, a pattern that starts to make sense. Dad believed that the most important element of a photograph is what you leave out, so as to frame only what is most significant. But for himself, he seemed to want the opposite—to amass the world, gather it all up in his sights, to capture everything possible of this life. It wasn’t always comfortable, this deep, persistent hunger. But I recognized it in myself. For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt this way, too.

***

When the redbrick houses of Little Washington appeared over the final hill of the Fodderstack 10K Classic, I was so stunned and ecstatic, I began to sprint. My legs were on autopilot, the world funneling to a single point. All I wanted—all I had ever wanted in my whole life—was to cross the finish line and collapse in a jubilant heap at my father’s feet. I’d grown miraculous new legs, and they were powerful and fast, wheeling me along to him. I could pick Dad out from half a block away: five feet eleven inches, navy-blue crewneck sweatshirt, khaki work pants. Meg was gone, ahead of or behind me; it no longer mattered. With two hundred feet to go down the home stretch, it was every girl for herself. I barreled across the finish line and straight into Dad, nearly knocking him over. My lungs were scorched, and my legs were spasming so hard from fatigue that I couldn’t have slowed down if I wanted to.

“I’ll be damned!” Dad bellowed, fumbling for his camera. But it was too late. Maybe it was my spastic, unexpected dash or the miraculous fact that I wasn’t lying crumpled in the fetal position on the side of the road, but he was too distracted and befuddled to get the shot.

Somehow I managed to lower myself onto the curb, where I slouched, panting and red-faced, until my heaving breath begin to settle. Dad handed me a Mountain Dew and patted me a few times on my back. I might have sat there all afternoon, stuffing my face with brownies from the finish-line picnic, but I could tell by the mischievous glint in Dad’s eye that we weren’t done yet. “Okay, girls,” he told Meg and me. “Now go back and pretend to crawl across the finish line!”

Dad was serious about his photographs, but he had a silly side, too. Often he’d arrange us into joke poses and fake scenarios, the exact opposite of his documentary pictures for National Geographic. “Stand up on that rock and look tough,” he’d say, positioning us on a mountaintop, chortling from behind the camera as we flexed and grimaced. “Okay, back up,” he’d joke. “Just one more step, and one more. Ha ha ha.”

Now Meg and I rose stiffly to our feet, groaning a little for effect. We limped a few feet onto the course and got down on our hands and knees, looking furtively around at the other runners. Dad pointed his camera. “Look like you’re really in pain!” he commanded, laughing, as we dragged ourselves over the fraying strip of duct tape laid across the road. Did he not realize we really were in pain? Obligingly we rearranged our faces into masks of pretend agony that only moments before had been real. Click, click, click went the shutter. “Okay, one more, just one more!”

Meg and I must have come in dead last that day, but it didn’t occur to me to care. In the picture Dad took of me, I’m grinning madly, all my freckles popping, my expression one of delirium and relief. I know that look. It’s a runner’s high. It’s the look that says I ran 6.2 miles and survived the improbable, and nothing will ever feel hard or annoying again! Not even posing like a fool on my hands and knees in front of complete strangers.

We drove back to his farm the same way we’d run, covering the same demented distance in not much more than fifteen minutes. Meg and I rode in the bed of Dad’s pickup, the wind slapping my hair, my legs stiff as logs, elated. Flooded with endorphins and a crazed surge of optimism, I had a flash of understanding: Suffering and perseverance were their own rewards. They could make me stronger. They could make all the tricky bits of life seem easier.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Can you also recall back to your past and see flashes of an ultrarunner being ‘born’ in your regular life? Can you share a story about it?