Being stiff is a drag. It can make all movement — not just running — range in feel from uncomfortable to downright miserable. Yet, the only thing more miserable than stiffness is devoting huge efforts into stretching without any improvement. Muscles and joints are stiff as ever and running remains slow and uncomfortable.

Being stiff is a drag. It can make all movement — not just running — range in feel from uncomfortable to downright miserable. Yet, the only thing more miserable than stiffness is devoting huge efforts into stretching without any improvement. Muscles and joints are stiff as ever and running remains slow and uncomfortable.

And while stiffness may seem to be a typical part of aging, many masters runners are able to maintain their mobility, performance, and enjoyment of running.

As stiffness began to personally affect me over the past few years, I doubled down on efforts inside the clinic and out to find out why. What is responsible for stubborn stiffness and what, exactly, must we work on to stay mobile?

After 25 years of running, 20 years of coaching, and 13 years of physical therapy practice, I’m rounding toward the answer: fascia.

Seeking Truth, Hands-On

I do a lot of hands-on treatment in my physical therapy practice. And with each passing year, I find myself doing more manual therapy treatment than the year before.

This is increasingly ironic. I entered the profession as both a competitive athlete and committed running coach. Optimization through exercise and movement coaching were huge values of mine. So why so much hands-on treatment?

It gets results. Results happen much faster than exercise, and often when stretching, strengthening, and motor control fail altogether. The more patients I successfully treat, the more often I see cases with complex and stubborn dysfunctions that only my hands — as part of a whole-body, systems-based approach — can create the changes necessary for pain relief and healthy, sustainable running.

But as my hands-on treatment emphasis has increased, so, too has the quality and nuance of treatment. It’s no longer good enough to push or pull on a given body part to facilitate movement. Whether I do it with my hands, or a runner does it to themselves with a foam roller, yoga class, or massage gun, the effectiveness of a mobility strategy depends on what specific type of tissue needs to move, and what is preventing that motion.

The author Joe Uhan (left) at a manual-therapy certification class in 2019. Photo courtesy of Joe Uhan.

What Actually Needs to Move and Why Stretching Often Fails

As outlined several years ago, there are several types of tissue that need to move for pain and injury relief and prevention, and efficient running. They include:

- Muscles

- Bones

- Nerves

I’d like to expand upon that list, by adding:

- Soft tissues — These include all muscles, but also all connective tissues like tendons and ligaments.

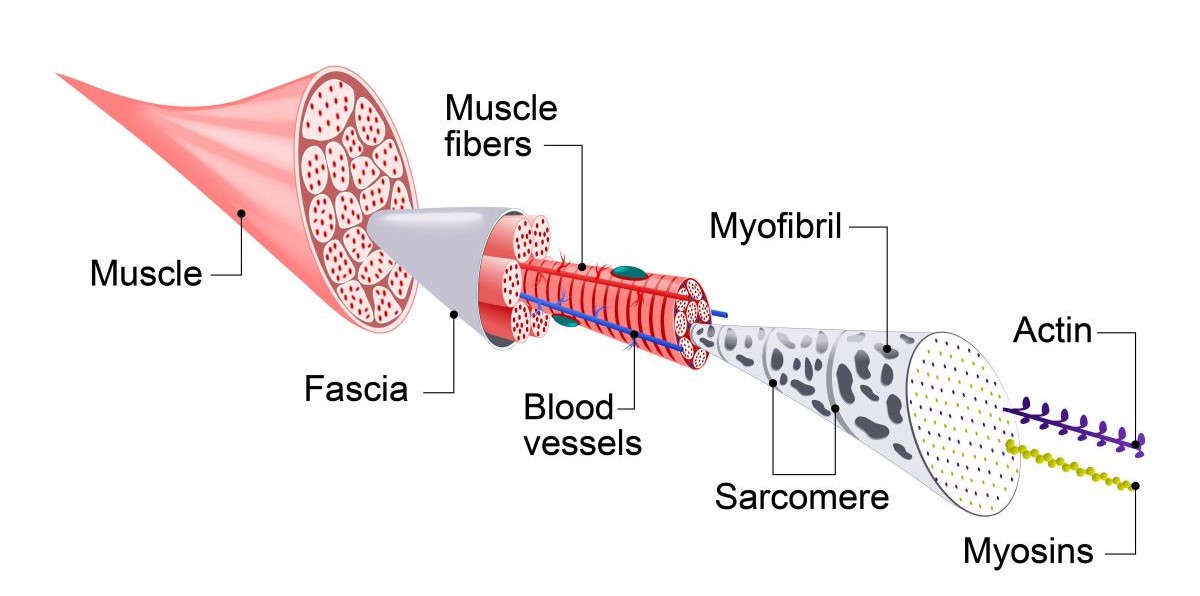

- Fascia — This is the granddaddy of all connective tissues that covers and connects everything, including skin, muscle, bones, nerves, blood vessels, and organs.

Understanding what exact tissue type is restricting motion is crucial for sustainable mobility improvement.

Because if we simply do the movement — say, stretch a hip into extension when it seems a hip flexor is tight — we often only get temporary improvement. This is because something else is restricting that functional movement.

How do you know what needs to move? It takes a lot of failure — clinically and personally — to learn the lessons of sustainable improvement.

When In Doubt, It’s the Fascia

But with successive failures and redemptive victories, the answer is becoming increasingly clear. When in doubt, it’s the fascia.

Fascia covers and connects everything. Developmentally, fascia grows first — as a sort of scaffolding — then tissues (bones, muscles, and connective tissue) grow into the spaces fascia provides. It is both structure and function. Thus, its ubiquity and multi-purpose function make it difficult to ignore.

Moreover, as we recently covered, healthy fascia is warm, soft, hydrated, and thus mobile. But when it loses any of those things, trouble can arise. If fascia loses mobility, anything it touches can also lose motion.

Indeed, fascia can restrict healthy muscle and tendon mobility. In fact, fascial tension (locally or regionally) can restrict motion so much that a given muscle or tendon can intrinsically strain. But whose fault is it? A “weak” and “tight” muscle, or a fascia that fails to allow it to function normally?

Let’s look at a couple of specific examples:

Ankle Stiffness

A runner suffers a serious right inversion ankle sprain. It requires a couple of weeks on crutches, then a very slow return to running. Four years later, the right ankle is much stiffer into dorsiflexion than the right.

What tissue is causing the pain and range of motion loss, requiring treatment? Is it the soft tissue in the back of the ankle? Or is it the joints in the front?

Such complexity is one answer to why so many of us — both as athletes and clinicians — fail to get sustainable mobility improvement.

We do our prescribed wall or stair calf stretch. We do so because we or our clinician believe the calf muscle and fascia are responsible for the stiff ankle. But what if it is joint stiffness related to the tibia, fibula, and talus? In such cases, this ankle joint stretch is a far more effective option — and the “calf”/ankle mobility exercise I prescribe most frequently.

Fascial restrictions in and around the calf, but also the foot and ankle (front, sides, and back) can limit dorsiflexion. We are also realizing that fascial connections run the length of the body. Tightness in the upper leg — or even the upper body — can cause and maintain stubborn ankle stiffness.

Low Back Pain

A runner experiences chronic lumbar spine pain. Their low back is limited in forward flexion, with stiffness and pain not only in the back but also the sides of the pelvis.

Again, we ask this question: what tissue is causing the pain and range of motion loss, requiring treatment?

Is it soft tissue in the low back, or along the lateral margins of the pelvis? Or is it a stiff belly that fails to move to allow the forward folding? Or do the lumbar vertebrae need to be pushed posteriorly?

To treat, in addition to pushing lumbar vertebrae posteriorly through the belly, I both perform and prescribe belly mobilization to ensure the gut moves enough to allow the spine, pelvis, and hips to move efficiently.

In the low back, fascia surrounds the muscles as well as the bones in the abdomen, in front. The guts are also covered in fascia, and those neighboring layers must slide-and-glide atop one another for healthy, pain-free lumbopelvic motion. As such, I now recognize that every chronic lumbar pain client — regardless of activity or injury mechanism — has deficits of gut mobility.

Myofascial Pain Is a Deficit of Muscle Play

In another recent column, we discussed these fascial concepts when addressing lower leg and foot dysfunctions. In that piece, we outlined muscle play: the idea that adjacent tissues need to move relatively independently of one another.

If we go back to our ankle and low back examples, what this means is:

For the ankle, the muscles of the lower leg (those connecting to the tibia and fibula, in back and in front); the tendons and nerves of the medial shin; and the layers of tissue on the bottom of the foot (including, but not just the plantar fascia) need wiggle room between adjacent muscles and the bones to which they attach or run along.

For the low back, the muscles and fascia on the back and sides of the spine and pelvis need the same mobility, and the gut and various abdominal organs need to move on top and in front of the spine and pelvis.

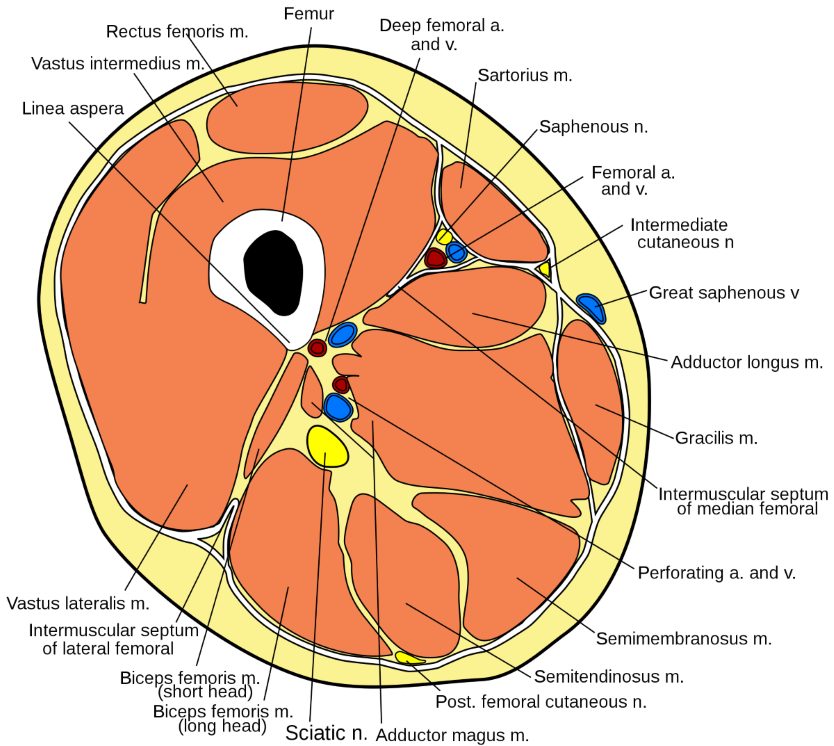

But the most fascinating example for runners may lie in the thigh. The thigh houses a large quantity and volume of muscles that move the leg in every possible direction. Yet they all connect to a single bone, the femur. But their function — and the source of much dysfunction — lies in the fascial connections between them.

The anatomy of the thigh. Photo: Gray432.png: Marshall Strotherderivative work: Mcstrother, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Even if we simplify things and note only six motions of the thigh — flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, and internal and external rotation — you have at least two dozen muscles, big and small, long and short, and thick and thin, that are both responsible for these individual motions and live right next to one another. As such, there is a high propensity for adjacent muscles that do opposing motions to stick to one another!

One example is iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome. The ITB is a wide expanse of fascia that covers the glutes and tensor fasciae latae and runs along the lateral thigh to insert at the knee. It largely stabilizes and modestly moves the hip and knee while walking and running.

The ITB itself often becomes painful, yet a sustainable pain-relieving strategy is elusive for many. Often, the ITB seems tight and great effort is put into stretching or otherwise trying to directly massage it.

But perhaps it is painful because its fascia is stuck to the tissue underlying it. The ITB can commonly get stuck to adjacent hamstrings (posteriorly), quadriceps (anteriorly), or to the pelvis and hip flexors (superiorly). My fastest and best ITB pain relief comes from freeing it — re-establishing muscle play — from the adjacent quads, hamstrings, and hip flexor muscles. This is, of course, in addition to restoring efficient pelvis, femur, and tibial-fibular motion and alignment.

Indeed, I am now finding that most of the hamstring and even hip flexor tightness I find as a clinician and athlete comes from the hamstrings being stuck to the adductors or quads, or lateral tissues like the glutes and hip rotators restricting the motion in more subtle ways — the “side doors.”

Indeed, the only sustainable improvement in my own hamstring flexibility has been through these strategies. Like many, conventional hamstring stretching, alone, no matter how diligent, has gotten me nowhere.

It seems that sustained pain relief and functional mobility are best achieved when the focus is on the fascia between muscles, bones, and all other tissues.

Heat, Soften, Hydrate, and Move: The Keys to Healthy Fascial Movement

Hydration

A couple of months ago, we discussed the importance of timing and hydration in mobility: to introduce motion and hydration in the morning, such that we can move efficiently early and throughout the day. In addition to a mobility jump-start, this implies that the chemistry (hydration) of fascia and its intrinsic fluid, hyaluronic acid, is optimal.

But getting the tissue hydrated can be a challenge when it is compressed and stuck together.

Staying hydrated throughout the day, not just during and right after running, is key to healthy fiscal movement. Here, David Sinclair rehydrates following the 2022 Canyons by UTMB 100k. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Heat and Soften

Research and practice in fascial mobilization have also shown that prolonged friction force has two positive effects on fascial mobility.

First, it softens tissues. This is the basis of the massage therapy profession: tissue techniques to decrease tissue stiffness, tone, and density through the application of manual force.

We now know, through in vivo studies, that prolonged friction also heats tissue. In doing so, researchers and practitioners, alike believe that the increased heat “melts” that sticky, dehydrated hyaluronic acid. This both promotes motion — like warming a stiff, solid glue — but also helps introduce hydration, which “thins” that sticky fluid and helps keep it less sticky.

Modern, self-treatment strategies — such as Graston-like or skin-scraping tools, and percussive massage guns — are effective ways to both mobilize various fascial layers while introducing heat.

Move!

Once one fascial layer is unglued from the other, it is now able and willing to lengthen, shorten, and otherwise move via conventional stretching and functional movements. Loosened fascia will allow standard mobility techniques, such as hamstring, hip flexor, or calf stretches, to create sustained mobility improvement.

The take-home lesson: real mobility gains require a focus on fascia, and this multi-faceted approach.

Take-Home Strategies for Runners

If you’re stiff, in pain, and/or your stretching attempts have gotten you nowhere, consider the following:

Find a Practitioner Who Understands Fascia

The easiest of all the strategies is to find a body worker who knows their anatomy and understands the structure and function of fascia. They can use their strong, high-stamina hands and elbows to provide targeted and sustained mobilization forces to your areas of need. This is a far easier, more efficient, and usually less painful alternative to the do-it-yourself approach.

But if that isn’t an option, you may be able to care for your issues in different ways.

Recognize the Side Doors

If you have pain or stiffness in fundamental motions — hip flexion and extension, hamstring lengthening, and calf and foot flexion — consider the “side doors.” These are adjacent tissues that may be pain-free, but could be significantly stiff and — through fascial connections — be perpetuating pain and stiffness in your sensitive areas.

For hip mobility, work the adductors and lateral glute muscles. For back and pelvic mobility, work the belly.

Learn Your Anatomy and Restore Muscle Play

Even a Google education in soft tissue anatomy will help you recognize the rich complexity of the human movement system, and all the places we can get stuck!

In doing so, it can help you use various tools — including scrapers, guns, balls, and even your hands — to target fascial tissue borders and help free one muscle from another. This might include ball massaging at the border between the ITB and hamstrings, or hands-on wiggling mobilization of the medial and lateral muscle play along the shin bone.

Soften, Heat, Hydrate, and Then Stretch

Once you’ve restored even a marginal amount of tissue freedom (say, between muscles, or between muscle and bone), then apply a stretch. Softened, warmed muscles will effectively move — and gain and maintain increased length — far better than by stretching, alone.

Final Thoughts

Stiffness is not a terminal illness. Indeed, of all the aging processes, there is no evidence that tissue mobility is permanently lost. Rather, tissues accumulate stiffness over both time and activity load. But, using these techniques, we can curb and even reverse those losses to not only improve mobility, but decrease pain and optimize function!

Call for Comments

- Do you suffer from stiffness?

- Did you find the above advice helpful?

- Is there anything else that’s worked well for you?