In the fall of 2014, I was invited to compete in the “France against the world” challenge as part of the Festival Des Templiers in Millau, France. A pretty intimidating title, I know. The American team consisted of myself, Sage Canaday, Zach Miller, Chris Vargo, and Matt Flaherty. We would be racing in the 78-kilometer Grand Trail des Templiers, called Les Templiers for short. At that point, it was the biggest ultrarunning event I had ever run, and I was beyond nervous.

During the summer of 2014, I had been focusing on the Skyrunner World Series. The series included classics like the Zegama Marathon, Mont Blanc Marathon, Sierre-Zinal, and the series final, the Limone Extreme Skyrace. I made the tough decision to race Limone in Italy just two weeks before heading to France for Les Templiers. The two races couldn’t be more different. Limone is a steep, technical 14-mile course with 7,500 feet of climbing and a screaming descent. Les Templiers is a rolling loop through multiple gorges in south-central France with about 13,000 feet of climbing stretched out over 48 miles. I came to France knowing that I was fit from the skyrunning season, but I wasn’t totally confident in my ultramarathon legs.

I remember purposely sitting in the back of the press conferences because I felt like I didn’t belong amidst the seasoned ultra veterans like Sage, Zach, and the numerous international stars like Benoit Cori, Sylvian Court, Nicolas Martin, Miguel Heras, and Jonas Budd. Even at meals with the rest of the athletes, I felt out of place. I just didn’t have the confidence that the others seemed to exude.

The author running during the early miles of the 2014 Les Templiers. All photos iRunFar unless otherwise noted.

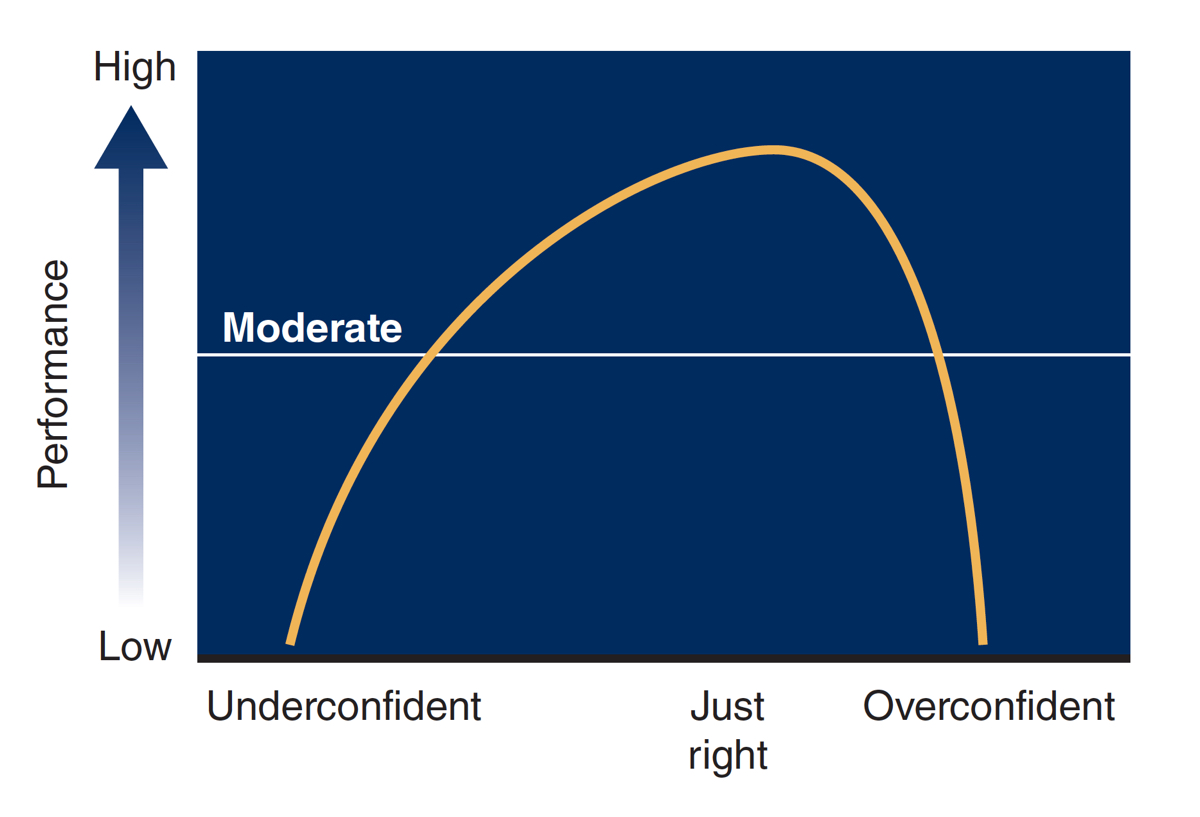

Confidence is a tricky thing. In sports, confidence can be the difference between success and failure. Confidence facilitates positive emotions, whereas a lack of confidence can spiral into a vicious cycle of negative self-fulling prophecies. I know I have experienced that vicious cycle when my expectation of failure has manifested itself into actual failure. A lack of confidence can lower self-image and increase expectations of a future failure, which then starts the cycle again.

Conversely, increased confidence can lead to what Weinberg and Gould describe as psychological momentum: “People who are confident in themselves and their abilities never give up. They view situations in which things are going against them as challenges and react with increased determination” (2). Psychological momentum not only helps us reshape the way we see challenges, it can even increase our physical effort and ability to preserve during a difficult task. Weinberg et al. found that, when ability levels were equal, the winners of competitions were the athletes who had the most self-confidence. This was especially true in competitions that involved athlete persistence, such as running a marathon or events lasting longer than three hours (1).

When these findings are applied to the ultramarathon world, the benefit of confidence is huge. If someone is confident in themselves, they will believe they can achieve their goals and will do everything in their power to succeed. Maintaining self-confidence can help a runner deal with unforeseen setbacks along the way, by viewing them as challenges rather than race-ending mistakes.

The inverted U of performance versus confidence. Image: Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2019). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. (2)

So then, how can we develop our own optimal confidence levels? A few of the most effective ways to produce ideal levels of confidence are self-reflection, goal setting, and logistical preparation. These three aspects of planning are slightly different, but they work together to create realistic expectations that we can use to maintain confidence in the moment.

Obviously, not everyone should come into a race with the confidence that they will win or set a course record. That level of overconfidence would be detrimental to their goals and could decrease performance when the goals are not met. This is when self-reflection can help to shape our expectations. In my case, I knew that I was coming into the race without a recent ultramarathon experience, but I also knew that my climbing legs had never been better. By reflecting on my training prior to the race, I was able to take a realistic look at the course, leverage my strengths, and mitigate my weaknesses. The step of taking a close look inward before looking out can help us assess how we feel, how training has gone, and what we can expect from ourselves.

After thinking self-reflectively about my fitness, I knew that I couldn’t set a goal to be in the lead at the first aid station, but I could create goals that supported strong running on the steepest portions of the course. By manipulating the situation to experience a sense of accomplishment during the race, I could keep my confidence levels high without becoming overconfident. For more mid-race goal-setting ideas, see my previous article on rethinking the aid station.

Another crucial aspect of goal setting and confidence comes from logistical preparation. In order to set goals that will elicit a feeling of accomplishment, we need to prepare for the situation. Someone who studies the race course in detail ahead of time–who knows where the difficult climbs and aid stations are, for example–will come into the race with more confidence because they know what’s coming. They will also be able to set specific goals for themselves along the way which will maintain their confidence levels as the race progresses.

Although I lacked confidence in the days leading up to Les Templiers, I did my best to study the course and come up with a detailed race plan. I created splits that I could shoot for along the way, giving myself the opportunity to feel a sense of accomplishment when I hit those splits, and planned out every calorie I would eat–down to the last gel. I still wasn’t sure how I would stack up to such tough competition, so I looked inward and created a plan that would allow me to run my own best race based on what I knew of the course.

When we lined up in the darkness of the start line, and the red flares glowed red along the road ahead, my mind was calm and I had a clear mission ahead of me: I was going to run my own race. The race started fast, but I knew that the second half of the race would be far steeper and more technical than the first half, so I waited and stuck to my plan. By the 35-kilometer mark, I was still outside of the top 20. As the race went on, I started to pass other runners who were struggling. Each runner I passed boosted my confidence and gave me hope that my plan was working. By 60k I had worked myself into the top five. My legs were beginning to fail, but I kept passing runners. I remember going by Sage Canaday on one of the final downhills. I was sad to see my teammate struggling, but that pass also gave me the extra confidence that I could keep pushing. I was suddenly in contention with guys who I previously thought were out of my league. That belief in myself gave me an extra gear. It was enough to push me past Miguel Heras and Zach Miller in the last few kilometers. I finished third and was followed closely by Sage and Zach. We won the team competition and defeated the French team on their home turf. That was one of my most memorable race finishes. My success was the result of careful self-reflection, goal setting, and self-confidence. And now, whenever I struggle with my self-confidence before races, I can think back on that day and know that believing in myself will help me keep pushing.

Call for Comments

- Can you think of a time where confidence helped you perform at your best?

- And how about a time where you had either too little or too much confidence in a race? What happened then?

References

- Weinberg, Robert S., et al. “Effect of public and private efficacy expectations on competitive performance.” Journal of Sport Psychology, vol. 2, no. 4, 1980, pp. 340–349.

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2019). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.