Have you ever run into an aid station while bonking your brains out, grabbed a few handfuls of who-knows-what, and then decided that you suddenly don’t have a moment to spare only to sprint out of the aid station and forget to drink any fluids? I have. Have you ever come into a late-night aid station like a zombie with no idea what you need, spend too many minutes deciding what looks good, and in your indecision grab a stale PB&J corner which you then puke back up a mile later? I’ve done that one, too. After hours of quiet on the trail, the overstimulation of an aid station can cause you to lose focus. And running for long distances can temporarily ruin an otherwise sharp mind. Over the years, I’ve learned to never trust my race-day decision-making capacity–especially in aid stations–and instead create a detailed plan. If I can plan my race, down to the very last detail, there is less for my dehydrated, oxygen-starved brain to worry about.

At the very core of my race-day plan is the aid station. I’m not talking about the magic healing power of communal M&M’s and potato chips, I’m talking about using aid stations as as an accountability tool and motivational oasis. Trail running is a unique sport because every so often we get the opportunity to pick up food and drink, check in with race volunteers, and perhaps even see our crews. If leveraged in the right ways, these moments can be incredibly useful.

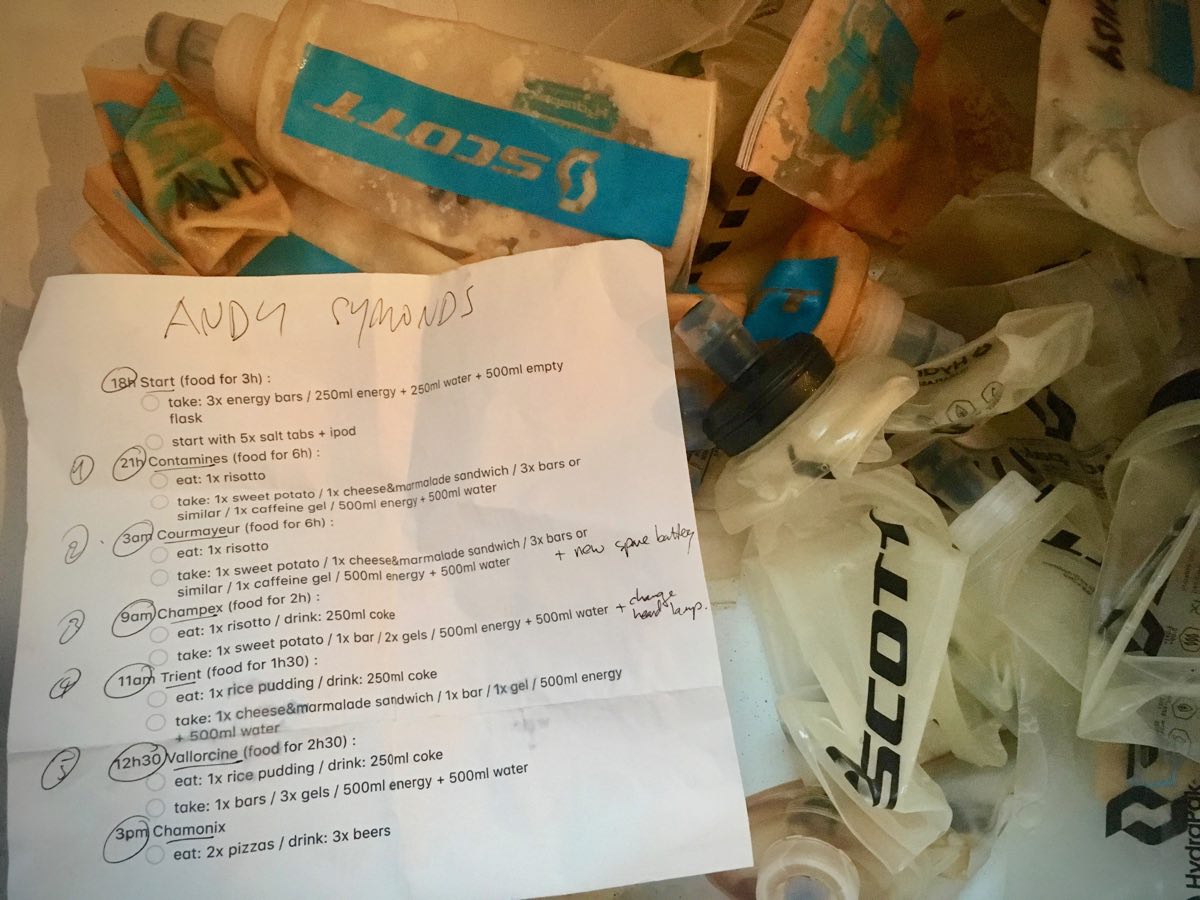

In order to take full advantage of aid stations, my process starts with an outline of my projected arrival times at each of them. Before a race, I sit down and estimate how long each segment between aid stations will take based on trail conditions and overall pace. Below is a great example that Andy Symonds used to plan out his fifth-place finish at the 2019 UTMB.

The plan Andy Symonds used to take fifth at the 2019 UTMB–including finish-line beer and pizza. Photo: Andy Symonds

As you can see on Andy’s outline, he listed how long he thought each segment between the stations would take. He then used that information to plan out his hydration and nutritional needs. This is the first way that I recommend using aid stations–to keep yourself accountable for eating and drinking. I won’t go into nutritional recommendations now, because it has been covered on iRunFar before, but by creating a plan like this, you will know exactly how much food or water you’ll need no matter how fried your brain might be.

Like Andy, I’m a fan of preparing softflasks with gel and fluids before the race, and then picking up new ones whenever I see my crew or can access my drop bags. If I have the option, I will even pack an entirely new running vest full of food and water to pick up at a crew station. This cuts down on transition time, as I can simply drop my old vest and pick up the new one from my crew. In order to make it as simple as possible, I pack only what I will need and keep my options to a minimum. I much prefer to keep my options limited, instead of packing everything I could possibly want. An aid-station stop that has too many options just gets confusing when I’m already exhausted. All of my drop bag/crew decisions are made ahead of time so that I can simply adhere to the plan on race day.

In longer races, I write out an abbreviated version of my plan on a notecard in a plastic baggie that I carry with me. This comes in handy when there is a long gap between crew stations and I have to rely on the regular aid stations. The note card keeps me from making fatigue-induced mistakes, like sprinting out of an aid station and forgetting to fill up on fluids. By preparing my food and fluid plan ahead of time, the only thing I need to worry about between aid stations is sticking to the plan–and running. At each station I know I should come in without any spare food, and then leave fully stocked with the amount listed on my plan and/or notecard. As long as I keep repeating that process, I keep myself on track.

The author switching packs with his crew at a Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile aid station. All photos courtesy of Alex Nichols unless otherwise noted.

The other way I would encourage you to rethink the aid station is based on the motivational tool of goal setting. Weinberg and Gould (1) explained that there are three types of goals: outcome, performance, and process. Outcome goals are based on the final result of an event and are dependent on more than just your own efforts, such as winning your age group in a race. Performance goals focus on standards of performance that are within your control, like running 100 miles in under 24 hours. Finally, process goals deal with the more minor steps that you take along the way to improve performance, such as maintaining a comfortable pace on a specific uphill.

In my own experience with ultrarunning, I have found performance and process goals to be an especially effective way to develop confidence during a race. Every time I line up for an ultramarathon, there is always a part of me that doubts I can actually run that far, so I try to break down the daunting distance into the more manageable chunks between aid stations. I can then prepare process and performance goals for each one of those chunks. For example, if I know that it will be 10 miles to the next aid station with a technical downhill, I can develop a process goal to watch my footing and a performance goal to keep my pace under nine minutes per mile. Those goals give me something to focus on during that stretch, and can also give me a motivational boost when I reach the next aid station and complete them. By breaking the race up into chunks designated by aid stations, the whole thing suddenly becomes far less intimidating. Looking at the race as a series of smaller segments can also be helpful if you find yourself in a bad patch. There will always be things that go wrong in a race. Instead of getting caught up in how the little mistakes might impact your outcome-based goals, you can use each aid station to reset and focus on accomplishing the next smaller goal. Even if the last stretch didn’t go as planned, you can focus on accomplishing your goals by the next aid station.

With a little planning and forethought, aid stations can be a huge resource to trail runners. They can be used to implement your nutrition and hydration strategy, and also to make an intimidating race more manageable. Aid stations can be your lifeline when you need it most and help you develop confidence in your own abilities. Fatigue, distraction, and irrational thinking are almost guaranteed when racing long distances, but by making a detailed plan, eliminating decision making, and breaking the race up into smaller segments, you can work through the fatigue and accomplish your goals.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- How do you optimize your visits to aid stations? Do you use them to create small goals? Are they motivational to you because you can resupply on food and drink, and see other people such as volunteers and your crew?

- What mistakes have you previously made at aid stations, such as forgetting to take food or drink when you are tired or being distracted by too many food choices?

References

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2019). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.