From outdoor-sports expos to your social media feed, and from the farmers market to your local grocery store, you’ve surely seen many products marketed as containing “CBD,” the acronym for cannabidiol. Touted as a cure-all, you can now find CBD in lotions, balms, rubs, gummies, oils, beverages, and powders. The list goes on, and with it the interest of the general public has accelerated as well. In fact, in just the month of April in 2019, there were 6.4 million Google searches for CBD (7).

What exactly is CBD and is it worth all the hype? In this article, we explore the scientific literature on the physiological, biochemical, and psychological effects—or lack thereof—of CBD that might be relevant to you as a trail runner and ultrarunner.

What is CBD?

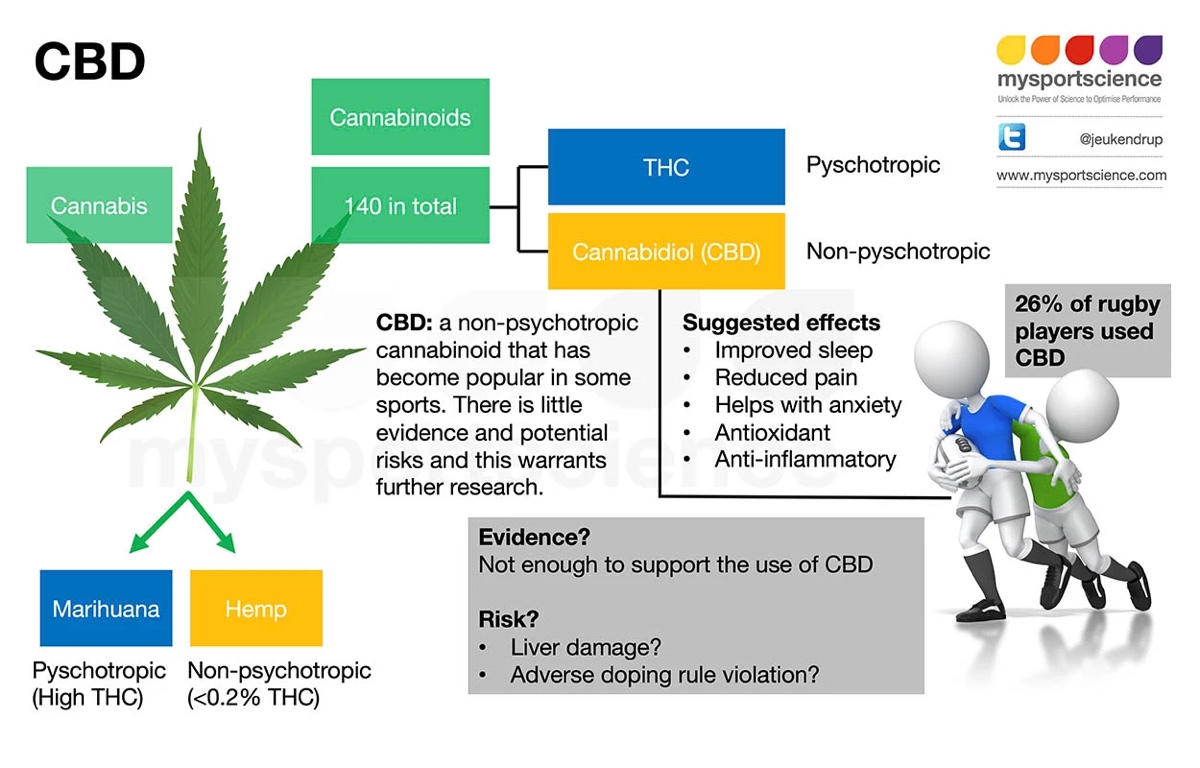

Cannabis, the plant most people call marijuana and hemp, contains at least 144 cannabinoids, the plant’s active compounds (1, 4). Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the most famous and most studied compound for its psychoactive effects and qualities. Another cannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD), has gained huge traction in the past half decade. Once thought to be biologically inactive, it’s now believed to have some therapeutic drug effect.

Biologically, hemp and marijuana are the same species. However, they are legally different as hemp plants must contain 0.3% or less THC content by dry weight, and marijuana has more than this. The CBD that we see on the market most commonly starts as hemp. The style in which the hemp plants are left to grow and be harvested is what determines if it’s used for industrial hemp or for harvesting cannabinoids. This is because the resin in the flowers of unfertilized female plants contains the most cannabinoids.

After harvest comes an extraction process. There are two common ways to extract CBD from plants, ethanol extraction and carbon-dioxide extraction. Ethanol extraction utilizes this high grain alcohol to separate CBD and other cannabinoids from the plant. Carbon-dioxide extraction happens under extremely low temperatures and high pressure to strip the hemp flowers of all cannabinoids.

The final steps of either extraction process is what leads to CBD oil variations. In what’s called CBD isolate, all other cannabinoids are removed, leaving only CBD molecules behind. This should remove all meaningful amounts of other cannabinoids such as THC, but trace THC is still a possibility pending companies’ individual testing policies.

Full-spectrum CBD means that all other cannabinoids and aromatics are still present from the plant from which the CBD was extracted. Even in this case, there should not be enough THC to create a high, but there is risk that THC can build up in your system (pending so many individual factors) that you could test positive on highly sensitive drug tests, such as work drug tests.

So, know that when you use a CBD product, THC could be present. Although the risk of consuming, lathering, or inhaling enough THC to test positive for it in sports competition is highly unlikely, it is something to be weighed by everyone’s personal risk tolerance.

CBD Legality Among Governments and Anti-Doping Agencies

Let’s address the elephant in the room. Is CBD legal?

Cannabis, including CBD, has been widely researched in the medical community, and is approved in many places for sedation, convulsions (treatment for epilepsy), asthma, appetite stimulation (aiding patients undergoing chemotherapy), and muscle relaxation (3).

The rules on cannabis for use outside of medicine vary from country to country, and state by state. As for CBD specifically, while CBD remains illegal in some countries and states around the world, it is fairly widely legal at this time.

What about cannabis’s and CBD’s legality for athletes? Enter the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). WADA’s role is to monitor worldwide anti-doping activities by implementing the World Anti-Doping Code through extensive drug testing both in and outside competition alongside national anti-doping organizations like the United States Anti-Doping Agency. As part of this, WADA maintains an extensive list of banned substances. In order to be included on the list a substance or method must meet two of three criteria (8):

- Medical or other scientific evidence that the substance or method (alone or in combination) enhances sports performance.

- Medical or other scientific evidence that the use of the substance or method (alone or in combination) represents an actual or potential risk to the athlete.

- WADA’s determination that the substance or method violates the spirit of sport.

Starting in 2004, cannabis found itself on that list (3) as a Substance of Abuse because it is, per WADA’s views, frequently abused in society outside the context of sport (6). Cannabis has traditionally been banned in competition but only above a certain threshold, meaning that WADA allows its use out of competition so long as its presence in your body during competition is below a certain level. The threshold has changed a lot since first implemented as research and scientific understanding increases, and as of 2021 the allowable urine concentration is 180 nanograms per milliliter. For reference, most workplace drug tests have a threshold of 50 nanograms per milliliter or even lower (3, 6).

It took a long time for WADA to differentiate between the numerous chemical compounds in cannabis. It wasn’t until 2018 that WADA removed the starlet of our article, CBD, from the banned list while leaving all other cannabinoids forbidden for in-competition use.

The Physiology of the Endocannabinoid System and Cannabinoids

Many organisms, including humans, have an endocannabinoid system (ECS), which is composed of endocannabinoids (cannabinoids that we produce inside our bodies) and endocannabinoid receptors (sites inside of us where endocannabinoids bind) called CB1 and CB2 (9). CB1 receptors are abundant throughout our central nervous system (our brain and spinal cord), whereas CB2 receptors are found throughout our peripheral nervous system (nervous-system tissue apart from our brain and spinal cord, particularly in our immune cells).

Why would we possess such a system? With their wide reach throughout our body, it’s believed that the ECS helps regulate many different body systems to maintain homeostasis, or our body’s happy place. An example of this is the endocannabinoid anandamide. Anandamide has been linked to the neural generation of motivation and pleasure, appetite regulation, and is often associated with the famous “runner’s high.” In fact, runners and cyclists have been shown to have higher levels of anandamide compared to sedentary individuals after just 45 minutes of exercise (3).

Another abundant endocannabinoid is 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). 2-AG has similar physiological effects as anandamide, like regulating appetite and generating pleasure, but it’s also believed to have a more important role in your immune system. This is because 2-AG is expressed abundantly in your peripheral immune cells and is thought to play a role in anti-inflammation.

Now, enter external cannabinoids, which can also work in our bodies like endocannabinoids (9). For example, when THC enters your system, it binds rapidly to your CB1 receptors and essentially mimics the endocannabinoid anandamide, creating a sense of euphoria. Differently, CBD seems to have a very low affinity for binding to CB1 receptors, acting only in conjunction with THC, which might help limit some of the hallucinogenic effects of THC when ingested in combination. At best, CBD only partially acts on CB2 receptors.

So if CBD doesn’t bind well on its own to our CB1 receptors and has only a modest effect on CB2 receptors, then how is CBD utilized in our bodies? First, CBD might be most helpful by slowing down the breakdown of endocannabinoids in our brains and blood plasma, thus extending their positive effects.

Second, CBD may play a role by activating and blocking specific neurotransmitter receptors. For example, CBD may activate the serotonin 1A receptor for the chemical serotonin, which our body produces and makes us feel happy. And CBD may block the G protein-coupled receptor 55, which attenuates synaptic transmission, slows neural communication, and creates anti-epileptic effects.

Finally, CBD also seems to bind well to other receptors that work in parallel to our ECS on homeostasis, specifically our transient receptor potential channels, which help detect and regulate body temperature, the sensation of hot and cold, and the sensation of pain. (You might recall that we talked about these channels in our article about exercise-induced muscle cramps.)

However, we are still in the early stages of researching CBD in a meaningful way, and many studies so far have only utilized non-human animal models. We’d love to see these studies adapted and repeated in human populations, especially in athletic populations if we are to best understand how CBD affects exercise performance.

Does CBD Enhance Sports Performance?

It’s understandable why CBD is attractive to athletes, as a sports-legal, non-intoxicating substance with potentially beneficial pharmacological qualities. The qualities with the most scientific backing at present include anti-inflammatory and pain-reducing properties, anxiety-reducing properties, and as a potential sleep aid (10).

There are other properties that are reported in the media and touted by companies, including reducing exercise-induced gastrointestinal distress, improving bone health, reducing illness and infection, and aiding thermoregulation, but there is even less evidence in the literature to support these claims.

Of note, controlled studies done clinically use high doses of CBD to see effects, often about 60 milligrams/kilogram of body weight/day. That is, studies at 20 to 40 milligrams/kilogram of body weight/day showed no effects (4, 10). Most products on the market have a serving size of 10 to 30 milligrams. As you can see, recommended product doses are way lower than the dosing required to see positive effects in these studies. And super-high CBD dosing may pose a health risk via liver toxicity as it has to do the grunt work of breaking down CBD (12).

Beyond dose, we also have the question of effective delivery methods. Many animal models showed that injection or oral ingestion of CBD was more effective than transdermal applications of CBD.

As an Anti-Inflammatory Aid and Pain Reducer

We know that exercise can cause ultrastructural damage to our skeletal muscles, and that this exercise-induced muscle damage impairs muscle function and creates an inflammatory response (4).

Our immune cells respond to inflammation and additionally act on our transient receptor potential channels that receive pain sensation throughout our body. As stated earlier, we know that CBD may act on these parts of our body, so it’s not illogical to wager that CBD might help attenuate inflammation and pain in response to exercise-induced muscle damage, which in and of itself would be good and which could also present an interesting alternative to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

For Anxiety Reduction

Although we are willing to step up to daunting start lines, we trail runners and ultrarunners are not immune to fear and anxiety. We have previously discussed how these emotions can impede sports performance.

Early studies in mice suggest that CBD has the ability to bind with our serotonin 1A receptors in the regions of the brain involved in anxiety such as the limbic and paralimbic brain structures (10, 11). For now, there is still much to be learned about CBD and human brain tissue but there is promise in this area of research for runners who have anxiety disorders or race-day performance anxiety.

To Promote Sleep

Quality sleep has long been connected with sports performance, and we’ve explored the science of sleep in depth here on iRunFar.

The scientific literature is pretty mixed on CBD as a sleep aid, with its effects having to do largely with dosage. Also interestingly, it seems that high doses are most likely to cause a sedating effect and facilitate sleep, whereas low doses might actually increase wakefulness (which could actually be a benefit in a long ultramarathon, but that’s a separate idea) (4, 10). The studies that saw the greatest influence of CBD on sleep were in cases involving sleep disorders like insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or anxiety in comparison to the rest of the population.

The Key Takeaways of Current CBD Science

As an optimistic skeptic, a coach, a scientist, and a runner, I think the hype isn’t entirely unwarranted. However, the evidence is not yet scientifically strong enough for me to personally purchase or advise other people to purchase CBD products for the purpose of benefiting their athletic performance. Here are our current key takeaways:

- The scientific research is young, and there is a lot of room for validity to grow or reduce in any of the realms we’ve discussed.

- Be a discerning information consumer. Marketing from companies making CBD products and athletes they sponsor do not equal independent scientific research.

- The placebo effect is very real, and shouldn’t discounted.

- Know that THC could be present in trace quantities in the CBD products you use. Although the risk of consuming enough THC, even in full spectrum CBD, to test positive for it in sports competition is highly unlikely, it’s something to be weighed by your personal risk tolerance.

- CBD is expensive, particularly if used in dosages proposed in the literature to be effective.

- Finally, high CBD dosing may pose a risk to liver health.

Call for Comments

- Let us know your thoughts on the current science of using CBD for sports performance.

- Do you use medically administered CBD for any health conditions? Leave a comment if you’d like to share your story.

References

- Babson, K. A., Sottile, J., & Morabito, D. (2017). Cannabis, cannabinoids, and sleep: A review of the literature.Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(4). doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0775-9

- Huestis MA, Mazzoni I, Rabin O. Cannabis in sport: anti-doping perspective. Sports Med. 2011;41(11):949–66.

- Kennedy, M. C. (2017). Cannabis: Exercise performance and sport. a systematic review.Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(9), 825-829. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.03.012

- McCartney, D., Benson, M. J., Desbrow, B., Irwin, C., Suraev, A., & McGregor, I. S. (2020). Cannabidiol and sports performance: A narrative review of relevant evidence and recommendations for future research.Sports Medicine – Open, 6(1). doi:10.1186/s40798-020-00251-0

- Mackie, K. (2008). Cannabinoid receptors: Where they are and what they do.Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 20(S1), 10-14. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01671.x

- SUBSTANCES OF ABUSE UNDER THE 2021 WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE GUIDANCE NOTE FOR ANTI-DOPING ORGANIZATIONS. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/2020-01-11_guidance_note_on_substances_of_abuse_en_0.pdf

- Leas EC, Nobles AL, Caputi TL, Dredze M, Smith DM, Ayers JW. Trends in Internet Searches for Cannabidiol (CBD) in the United States. JAMA Netw Open.2019;2(10):e1913853. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13853

- Heuberger, J. A., & Cohen, A. F. (2018). Review of wada prohibited substances: Limited evidence for performance-enhancing effects.Sports Medicine, 49(4), 525-539. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-1014-1

- Lu, H. C., & Mackie, K. (2016). An Introduction to the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Biological psychiatry, 79(7), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.028

- Gamelin FX, Cuvelier G, Mendes A, Aucouturier J, Berthoin S, Di Marzo V, Heyman E. Cannabidiol in sport: Ergogenic or else? Pharmacol Res. 2020 Jun;156:104764. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104764. Epub 2020 Mar 20. PMID: 32205233.

- Martínez-Aguirre, C., Carmona-Cruz, F., Velasco, A. L., Velasco, F., Aguado-Carrillo, G., Cuéllar-Herrera, M., & Rocha, L. (2020). Cannabidiol acts At 5-HT1A receptors in the human Brain: Relevance for treating temporal lobe epilepsy.Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 14. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2020.611278

- Kasper, G. (2021, May 04). Cannabidiol (cbd) for athletes. Retrieved May 15, 2021, from https://www.mysportscience.com/post/cbd-for-athletes