[Editor’s Note: Welcome to iRunFar’s Community Voices column for April! This month, we share Luke Kubacki’s creative writing. Luke is a reader and runner who recently moved to Chicago, Illinois to take a stab at getting into medical school. You’ll find him jogging in place at seemingly infinite stoplights, always wearing blue. Each month in 2019, we are showcasing the work of a writer, visual artist, or other creative type from within our global trail running and ultrarunning community. Our goal is to tell stories about our sport in creative and innovative ways. Read more about the concept in our launch article. We invite you to submit your work for consideration!]

“The little A-frame cabin was back up in a thicket of tall straight pines and waist-thick live oak and looked like it belonged…”

Out State Road 26 toward Newberry, west of Gainesville in the Magnolia hills of central Florida, there is a cabin. It’s not raised on a sumptuous knoll. It doesn’t hold sentry over a fantastic view. It’s not on any cabin-rental websites or Airbnb. It’s actually relatively hard to find, backed into that thicket of tall straight pines and waist-thick live oak. And yet, in the 1970s, this cabin hosted a soon-to-be Olympian as the rains of Central Florida’s winter months captured “all of life in the gray rumble of its clouds and the wetness of its seepage.” This runner went on to win silver at the Montreal Olympics in the 1,500-meter run.

Except Ivo Van Damme, the giant Belgian, won silver in the 1,500 in Montreal. And Mr. Van Damme, as far as anyone knows, never spent any time in central Florida.

“We are speaking of human endeavor and delusional systems…”

Historian Yuval Noah Harari credits homo sapiens’s unique ability to create and believe ‘fictions’ as the fulcrum characteristic that shot them to the top of the food chain. But when he refers to fictions, Harari isn’t citing the novel or short story; rather, ‘fictions’ refer to the ability to believe in something that either does not exist, or does not exist yet—an ability exhibited by no other species. Fictions are, simply put, the stories we tell and the symbols we use to tell them.

While these fictions allow us to cooperate with other humans for our basic needs, they also allow us to know ourselves and our place in the world. Harari, in his book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, explores the example of doors. Western architecture, he points out, allows many children their own room, an autonomous space that is sealed by a door with which they regulate their interaction with the world. Doors are a symbol of privacy and autonomy. “Somebody growing up in such a space,” he concludes, “cannot help but imagine himself ‘an individual’, his true worth emanating from within rather than from without.” Children grow up surrounded by these symbols and stories that teach them what it means to be a person.

“This one, he thought, what is it with this one?”

By my 1oth birthday, my family was living a relatively transient lifestyle in Brazil, far from our American citizenry, as my medical-doctor father served rural populations with medical care. I was familiar with the cyclical chaos of moving with its goodbyes, vaccines, visa applications, and neck pillows. The year I turned 14, however, was more tumultuous than the others. It started in a small city in the Brazilian state of Pará where we lived on a hill and swam in culverts underneath dusty red roads. We then bussed to Salvador, the Bahian coastal city where we watched men beat homemade drums and dance capoeira along beach trails. From there, we flew to an American Midwestern city where we fucking gorged on Taco Bell and learned that Katy Perry had kissed a girl and liked it. The week of my 14th birthday, we were back in Brazil, packing our blue Rubbermaids full of belongings onto an overnight boat bound for a Xingu river town that, at the time, had yet to connect to the outside world via road. This town was called Porto de Moz. We stayed there a while.

“I am speaking of countrified air…”

My father, a believer in both discipline and the benefit of physical activity, required his brood of four to exercise daily. We were given a choice: 30 minutes of intense exercise like running or swimming or 60 minutes of lighter exercise like walking or biking. Porto de Moz is an exposed river-beach town within drifting distance of the equator and the ever-present equatorial sun meant that minutes spent away from shade were tortuous ones. Especially for us pasty gringo kids, an hour of slow minutes could produce seeping blisters that left pink scars across our collar bones. So all four of us opted, most often, to run.

Not far from the small, concrete house we rented in Porto de Moz, through a sliver of creeping jungle arbor, was an airstrip. As I heard it, the airstrip was built by the municipality in anticipation of a weekly commercial flight to the capital, but then abandoned after a couple months of single-digit passenger loads. With no flights to dodge, the community found a new use for the enormous concrete slab. Starting around 4 p.m., as the afternoon heat began to wane, people would travel the three-kilometer loop that began and ended at the crumbling, single-room terminal. The purpose of the loop was exercise, but also performance; the collective arrived so groomed and perfumed that the wooden benches began to smell like melting hair gel and sweaty cologne. At the time of our arrival to town, this daily event attracted upward of 50 walkers or joggers. And 14-year-old me, in order to fulfill my daily mandate, joined them.

And my body responded. I had few friends and bountiful time, so running, as running tends to, drew me in. I ran along the river beach where fishing boats pulled ashore to clean their hulls. I ran to the docks where the barges tied up and boys threw trash at me calling, “Ei gringooo!” Searching for solitude, I found various routes through the forest north of town, occasionally hopping snakes and always stomping the ants that swarmed idle feet. But most often, I ran the airstrip.

One afternoon, discontented with my usual single lap, I spontaneously decided to run not two, and not three, but four laps around the circumference—a distance of about seven miles. I chugged some water, set out slow, and ran until dark.

I finished and though I don’t remember it being all that difficult, I felt a tinge in my right ankle as I slowed. By that evening, my right leg wouldn’t bear weight. Two days later, same story. After I described my pain, my father pulled up a chair and propped my foot on it. He pushed on my shin and asked where I felt it. I pointed to my outer ankle where, as an x-ray later confirmed, a crack in the bone compounded the downward pressure as a painful pinch.

The stress fracture itself was not a pivotal moment in my personal history; it was the idle time that followed. Running, which had become an interesting—if mandated—pastime became a roiling passion because, as many lonely kids do, I began to read.

“A runner who could not run was out of his element…”

I also began to write. My early journals from that time, while often hilarious to read, are heavy with an anxious search for personal meaning. Sociologists call children like me ‘third culture kids:’ children raised away from a ‘home’ culture but never completely assimilated into a resident culture. Disengaged from both, we carve for ourselves a third option, a third culture, pounded together by our own experiences.

Ruth Van Reken and David Pollock’s book Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds cites a therapist as saying that one of the greatest challenges she found among her third-culture clients was that “few of them had any idea what it meant to be a person.” While this quote is vague and severe, my teenage scrawls could be footnoted as supporting evidence. In one especially relevant entry, I lambast myself for my fluctuating personality between languages. In Portuguese, I spoke with the dramatic syntax that linguists now ascribe to Brazilian Portuguese while in English, I spoke slower and with a more even tone (though often with a Canadian lilt because I found that American girls lost their shit if I toned up at the end of a sentence). My social persona was like an article of clothing that I could change at will, making me a generally likable and utterly confused kid with very little idea “what it meant to be a person.”

But recently, as I read about Harari’s social fictions, with his symbolic doors and imagined realities, the tone of my teenage introspection made more sense. Of course the fictions that are meant to help us build our identity will change depending on the culture of the place. And of course the difference between the two will confuse a young person stuck in between.

That confusion is clear in nearly all my journal entries from that time. But something else is also clear: I loved to run.

“It was all joy and woe, hard as a diamond; it made him feel weary beyond comprehension. But it also made him free…”

With my ankle swollen and elevated, I took to the internet, which we had recently installed on the family’s desktop computer by running an ethernet cable three blocks from the town’s internet café. I found runners writing. More specifically, I found them blogging. I latched onto Jason Robillard’s irreverent and evangelical voice. I followed Bryon Powell as he blogged through a streak year. I learned what bourbon was from Patrick Sweeney. I read about Jesse Scott’s adventures in Michigan. A folder of Joe Grant’s photos fed the screensaver. I remember sitting at the computer, calculating the time difference to Boulder, Colorado, refreshing Anton Krupicka’s page, hoping that he’d post something soon.

(I would be remiss not to mention that I, too, started a trail-running blog during this time. I even sent out notices to some of my favorite writers, asking them to follow along. I deleted it, however, when my chapters-long treatises failed to go immediately viral.)

I read books too. I read Alan Sillitoe, Peter Snell, Neal Bascomb, Roger Bannister, Chris Lear, Hal Higdon, and others. By fateful coincidence, Christopher McDougall published Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the month I broke my leg, stretching my conception of running to include barefoot running, ultrarunning, Ann Trason, Death Valley, the endurance running hypothesis, and, the subject of a prolonged teenage crush, Jenn Shelton.

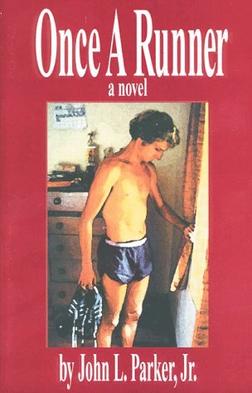

The cabin in the woods west of Gainesville does not, for all I know, physically exist. But it was during this season of life that I first read about Quenton Cassidy’s winter residence there. Originally self-published from the trunk of John L. Parker’s car, Once a Runner came to me as a ragged paperback tucked into a box of my dad’s old medical journals. I scoured that book like a bible. Scenes from Kernsville (based on Gainesville) enraptured me as runners logged their 120-mile weeks, spurned girls for intervals in the woods, whispered about symbolic demons chasing them to greatness (a greatness that was, to me, perfect), and jolted the bed with their 30-beats-per-minute cardiovascular systems. As a teenage boy with few friends and fewer mentors, the characters I found in those torn pages became just as real as the characters that I collected from the blogosphere, and their feats just as exhilarating.

The stress fracture healed and running resumed with perhaps too much fervor. I spent the years that followed resting from a range of overuse injuries, but the reading never stopped. While still feverishly refreshing the blog feeds of my favorites, I wandered into broader literary genres, adding names like Annie Dillard and Henry David Thoreau, Jack London and Jack Kerouac, Rachel Carson and Jon Krakauer, John Muir and Janisse Ray to my pantheon of influences. (I know, finally some women.)

I was collecting fictions. These fictions—in the form of characters and stories, real or imagined—helped me paint, for the first time, an image of the person I wanted to be; my own conception of “what it means to be a person.” Running became my third culture—its stories my legends—pushing me outside, faster and further. They became, in a sense, my anchors. Their values—the inherent worth of the natural world; the autonomy to shape my body into an efficient instrument of experience; the importance of movement; the fragility of personal barriers; pride in the process—weighed me to earth. To this day, they are some of the values I hold most dear.

“Hospitals and infirmaries; repositories of laboratory smells, lethal-looking silverware; launching pads for flagging hopes…”

That the stories we tell influence the people we become is not a new thought, but it has resonated with me recently. Not long ago, at the utterly confusing age of 23, I was diagnosed with cancer in a clinic in Maputo, Mozambique where I was working a job I loved. The flurry of activity that followed left me cancer-free (so far), but indebted, jobless, and directionless. Many of the stories I was telling myself at the time, the fictions I had collected, were suddenly out of my reach or empty, wiped pristine by the sanitized ethic of monumental change.

And so I found myself, once again, unable to run. Though this injury was deeper than my teenage stress fracture, and the scars were slower to grow, I returned once again to those old fictions when I noticed a folded copy of Once a Runner tucked in a box between old literary journals. I found the story resonated. I found the characters alive. I found passages underlined by my teenage self (now sprinkled as quotes throughout this piece) that reminded me of simple loops around a perfumed airstrip and the cliché-but-vital importance of putting one foot in front of the other.

In running literature and art about the natural world, our fictions have a unique power in that we cannot behold them without being pushed to action ourselves. They inspire movement. Quenton Cassidy never existed, but his toil toward a personal conception of greatness has been replicated in me and in us a thousand times over. And it will continue to replicate because, with the weight of our legends pulling us forward, we continue to run… not so that we may arrive, but so that we may move.

“The night joggers were out as usual…”

We need our fictions, our stories. We need our arenas, imagined like the cabin off State Road 26 and real like Mont Blanc. We need our heroes, fictional Quenton Cassidys and breathes-actual-air-and-eats-human-food Courtney Dauwalters. We need our legends that, in their grandiosity, teach us what is worth desiring. Because conceptions of greatness are not established alone, but by multitudes—

“…slowly pounding round and round the most infinite of footpaths.”

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- What parts of our community or the world have become your ‘fictions,’ to use the word of Yuval Noah Harari, the knowledge or experiences that help you know your place in the world?

- And what are your anchors? The people, places, and things that keep you connected to and moving forward upon planet earth?

Citations

- Harari, Yuval N., et al. Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind. Harper Perennial, 2015.

- Van Reken, Ruth & Pollock, David. Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2001.

- Parker, John L. Once a Runner. Scribner, 2010.