Runners, is your ‘Achilles heel’ your Achilles heel? Achilles-related pain is estimated to occur in nearly 10% of recreational runners every year (10) and over half of former elite male runners will experience it in their lifetime (23). Overuse injuries of the Achilles tendon are the most common reason for dropouts in athletic careers, especially in track and field (9). Loading of this tendon can reach up to 12.5 times a person’s body weight during running (6, 7) and the Achilles has a notoriously poor blood supply, so its ability to recover from injury is poor (1).

In this article, we discuss the most common types of heel pain, including Achilles tendonitis and plantar fasciopathy. However, we pay special attention to what has been termed a ‘mysterious’ yet ‘common’ heel-pain cause: Haglund’s deformity (20). Haglund’s deformity is where bone grows on the heel bone (calcaneus). This growth can cause pain and irritate the surrounding Achilles tendon and bursae (protective sacs). Together this collection of problems is called Haglund’s syndrome. We focus on Haglund’s deformity because:

- It seems to be diagnosed more and more often in the running community, but no studies have yet determined its prevalence;

- It closely mimics classic Achilles tendonitis but does not fully respond to/may get worse with the same treatments; and

- Why it develops and how to best treat it are still poorly understood.

As we await the study of Haglund’s deformity by the scientific community, we use this article to gather and organize runners’ anecdotal experiences to inform and perhaps benefit others with this injury.

An image showing Haglund’s syndrome in the right heel of Søren Rasmussen, a coach and 2:18 marathoner. Haglund’s syndrome is a bony growth that develops on the heel bone and creates bursitis and Achilles tendonitis. Image: Søren Rasmussen

The Basics of Heel Pain in Runners

The heel is fairly complex in its anatomy and determining the actual source of your pain can be quite challenging but necessary to start the right treatment.

Causes of Pain in the Back Portion of the Heel in Runners

- Achilles tendonitis in the middle of the tendon or where the tendon attaches to the calcaneus – This is the chronic inflammation of the Achilles tendon where the load on the tendon exceeds the tendon’s ability to heal. Repeat micro-tears and swelling develop within the tendon and the more inflamed the tendon becomes, the worse the blood supply to it is and the harder it is to heal. It is ‘easier’ for the body to create new bone than new tendon, so often little areas of calcium develop in the tendon. This is called calcific tendonitis and usually occurs where the tendon attaches to the calcaneus.

- Haglund’s deformity and/or syndrome – Haglund’s deformity is a bony growth/bone spur that develops on the calcaneus which can become painful when the bone rubs against a hard surface or when Haglund’s syndrome develops and there is associated inflammation of the bursae and Achilles tendon.

- Stress fracture –A stress fracture occurs due to repetitive load on the calcaneus, which may cause pain in the back or bottom of the heel.

- Achilles tendon tear/rupture – It is rare for a large Achilles tendon tear or rupture to develop in runners, but it can occur in a high-velocity injury. When a runner tells me they have an ‘Achilles tear,’ I usually figure it is a small tear that was identified and is a result of chronic Achilles tendonitis.

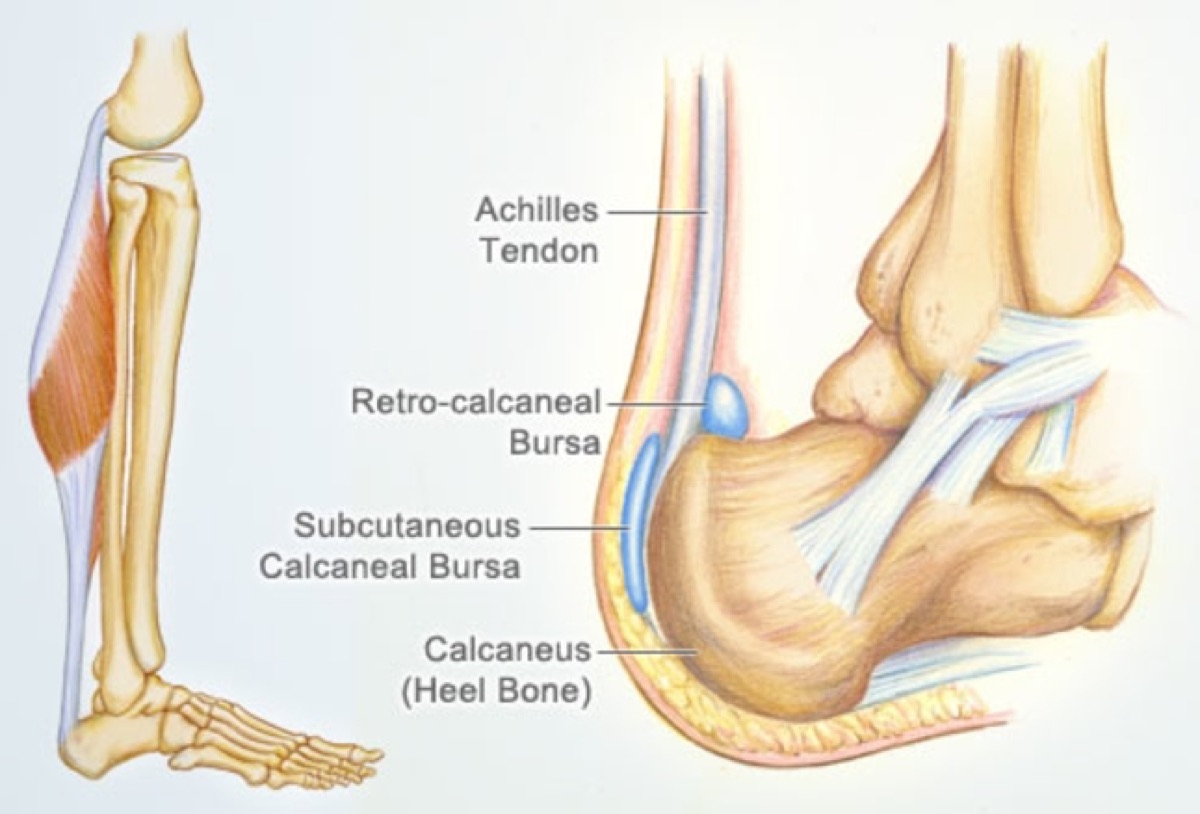

An illustration of heel anatomy showing the Achilles tendon, which is attached to the muscles of the calf above (gastrocnemius and soleus) and the calcaneus below. At the insertion of the Achilles on the calcaneus, there are two protective pads called bursae. Image: Webmd.com/fitness-exercise/picture-of-the-achilles-tendon#1

Causes of Pain in the Bottom Portion of the Heel in Runners

- Plantar fasciitis/fasciopathy – Plantar fasciitis, now called plantar fasciopoathy, is the most common cause of pain in this portion of the heel and is due to the same type of problem that leads to Achilles tendonitis. The load on the fascia exceeds its ability to heal and chronic inflammation develops. In fact, the plantar fascia is actually connected to the Achilles and is very similar structurally. This is why the treatments for Achilles tendonitis and plantar fasciopathy are similar.

- Fat pad atrophy – Fat pad atrophy is the second most common cause of heel pain on the bottom of the foot. It generally occurs in patients over the age of 40 and due to thinning of the fat pad on the bottom of the heel.

- Stress fracture – Again, a calcaneus stress fracture occurs due to repetitive load, and pain from it can manifest in the bottom or back of the heel.

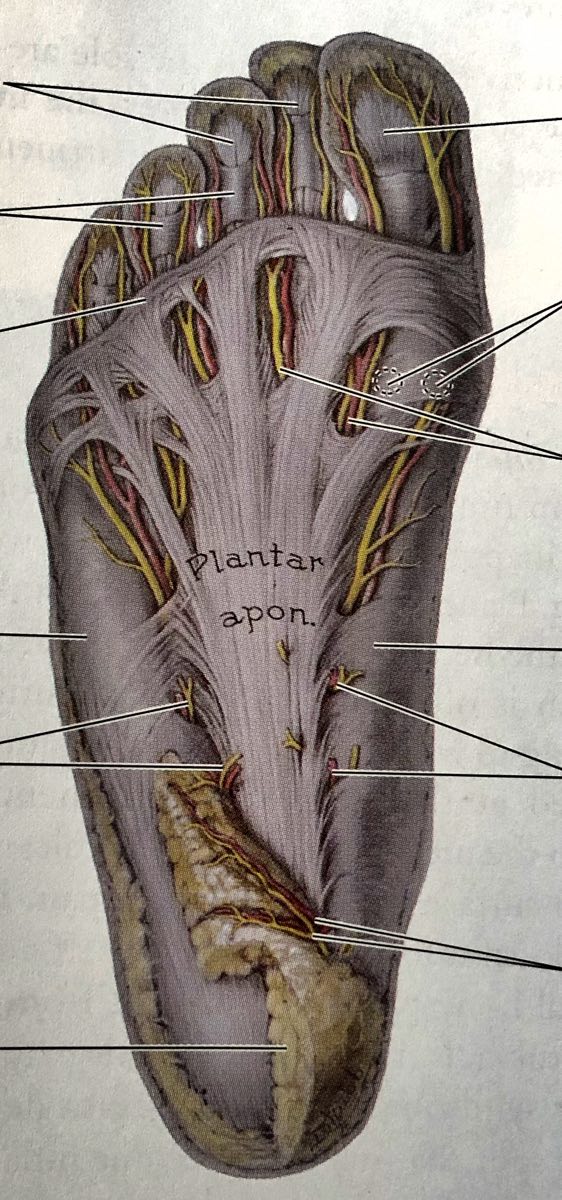

An illustration showing the plantar fascia (labeled ‘Plantar apon,’ short for plantar aponeurosis) which includes all of the visible white connective tissue. The left bottom line points to the heel’s fat pad. Image: Moore, 1999 (12)

There are other causes of heel pain not listed here, but these are the most common in runners. Let’s explore these specific conditions in more depth.

Achilles Tendonitis/Tendinosis in the Middle of the Tendon

Achilles tendonitis can occur in the middle of the Achilles tendon unrelated to any bony abnormality. This is called mid-substance Achilles tendonitis. Tendinosis is a term used to highlight the fact that it is a chronic condition. When the amount of load is too great and/or the blood supply insufficient for healing, micro-injuries accrue and lead to a chronic state of inflammation or tendonitis. The pain may be at its worst when getting out of bed in the morning, at the beginning or end of a run, or following a run. The pain does tend to ‘warm up’ in the middle of a run, unlike a stress fracture. Stretching also tends to relieve pain.

Strengthening the calf muscles, especially the soleus, increases the resilience and blood supply of the tendon and can be used to treat and prevent mid-substance Achilles tendonitis (2, 13). Heel lifts can also help in reducing pain due to tendonitis, but may put a runner at risk of shortening the tendon and potentially causing it to lose some of its elasticity. Chronic tendonitis may lead to bony enlargement/abnormalities on the calcaneus (5). Full-thickness tears can occur in the Achilles tendons of runners, but chronic tendonitis is much more common.

Insertional Achilles Tendonitis

This is tendonitis where the Achilles tendon attaches to the calcaneus and may include not only tendon swelling but also micro-tears and calcifications at the insertion site. Calcification can occur in a tendon as the body is attempting to heal it. Treatment may be the same as for mid-substance tendonitis, but if it is the calcification causing pain, then strength training will be less helpful and treatment should either focus on removing whatever is rubbing on the calcification (for example, the heel of running shoes) or removing the calcification through a needle or surgically.

Plantar Fasciopathy

Plantar fasciopathy, similarly to Achilles tendonitis, is due to damage of the plantar fascia at its origin on the calcaneus from the load on the fascia superseding its ability to heal. This typically causes pain in the sole of the heel and is at its worst in the morning when getting up from sleeping. The pain typically improves with running until it worsens at the end of and following a run. Ten percent of all people will have plantar fasciopathy in their lifetime (11) and running is a known risk factor (17).

Plantar fasciopathy can also be treated with high-load strength training of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles in the calf (15, 13). There is also growing evidence for the use of platelet rich plasma (PRP) to treat Achilles tendonitis (3), plantar fasciopathy (8, 14), and tendonitis in general. The theory behind its efficacy is that it both improves the blood flow to areas that classically have poor blood flow for the amount of work that is required of them and that it may have a direct analgesic effect. However, it’s not expected that PRP could remove calcification.

Calcaneal Stress Fracture

A calcaneal stress fracture should also be considered with heel pain. A stress fracture typically does not hurt after sleeping and worsens with running or weight-bearing activities. The risk factors and treatment for stress fractures have been discussed previously in our bone-health article.

Fat Pad Atrophy

Fat pad atrophy can occur at the front or back of the foot’s sole. It is diagnosed by the visible thinning (to less than three millimeters in thickness) on ultrasound of the fat pad and there tends to be pain at the heel center or margin, worsening pain when barefoot or after a long period of standing, and/or tenderness on the heel center. Fat pad atrophy is the second most common cause of heel pain on the sole of the foot and it tends to occur after the age of 40 due to age-related thinning of the fat pad. The fat pad loses water, collagen, and elastic tissue which together reduce its shock absorbency and protection (22). It may also occur due to a complication of a steroid injection in athletes at any age (18).

Haglund’s Deformity

Now, what is the ‘mysterious’ condition called Haglund’s deformity? Haglund’s deformity is a condition where a bony enlargement on the back of the calcaneus develops. Why this happens is poorly understood but potentially due to chronic Achilles tendonitis, wearing high-heeled shoes, and repeated rubbing/friction in the area. Tight Achilles tendons, high arches, ‘heredity,’ and rigid shoes have also been suggested as causes, but to my knowledge no high-quality study has yet been done to determine this condition’s cause (20).

Haglund’s deformity often becomes Haglund’s syndrome, which involves the bony growth plus bursitis plus Achilles tendonitis. Friction on the bony growth causes the other two problems to occur and all of this together can be really painful.

Diagnosis can be made with history, physical examination, possibly x-ray, and ultrasound. High-quality ultrasound may be more useful than x-ray as it can find very small bony growths.

Haglund’s Deformity Deep Dive

We’ll spend the rest of this article deep diving into Haglund’s deformity. I have had a Haglund’s deformity for years, and both ultrasound and x-ray imaging from mine over this time can help us understand the injury a little better.

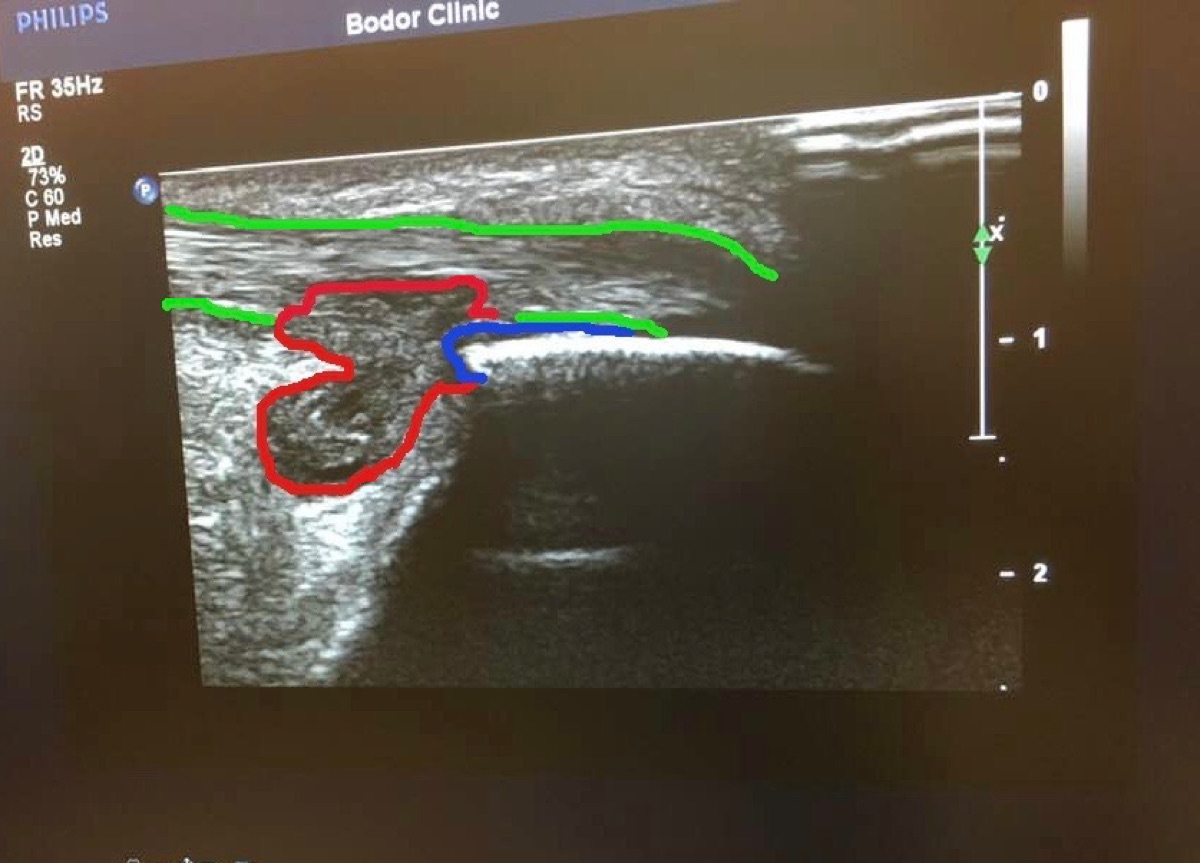

My ultrasound image shows classic Haglund’s syndrome. My swollen retrocalcaneal bursa is outlined in red, the bone spur is in blue, and the somewhat swollen Achilles tendon is in green. You can clearly see how the bone spur could rub the bursa, causing the bursa to leak into and push on the tendon. I was having pain at the time of this ultrasound. Image: Tracy Hoeg

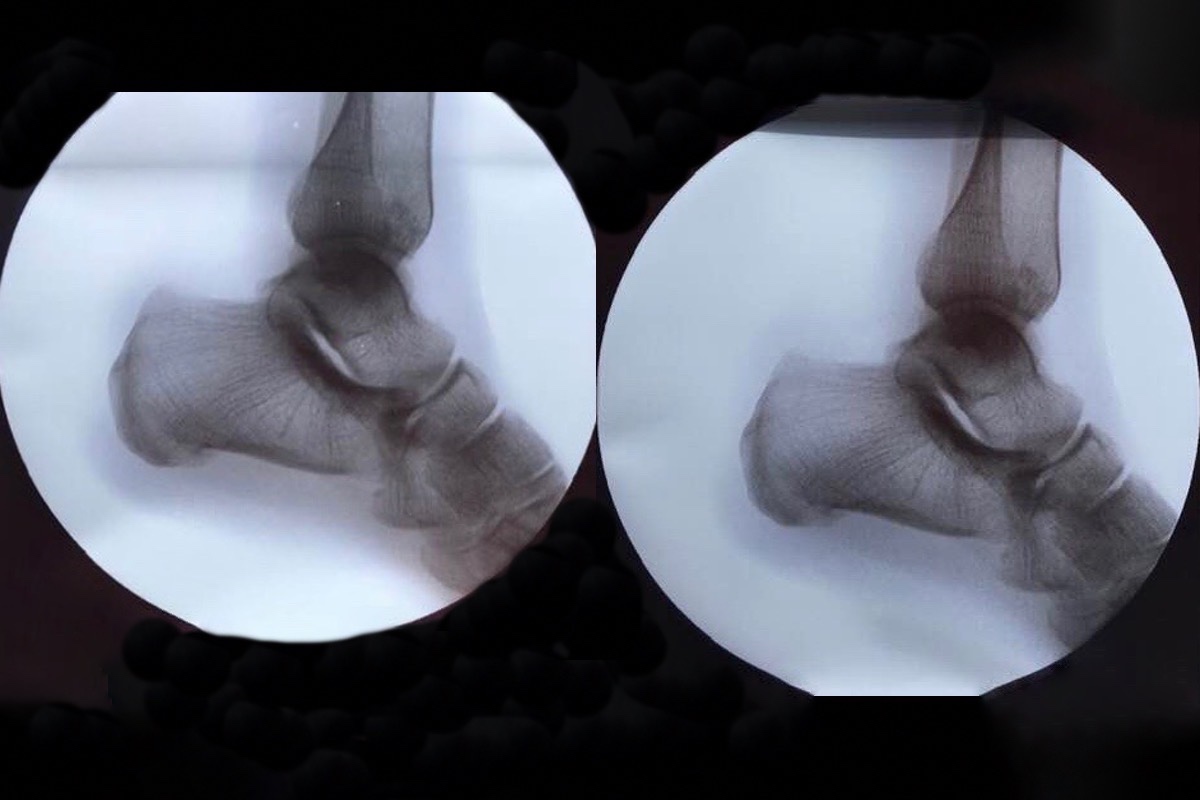

X-ray images of my two heels while I had Haglund’s syndrome symptoms. The left image is my affected heel and the right my uninjured heel. As you can see, the Haglund’s deformity cannot be seen on x-ray, though it was clearly visible on ultrasound. Image: Tracy Høeg

The increased use of ultrasound and awareness of the condition may be two of the reasons more and more people seem to be diagnosed with Haglund’s deformity. As for me, my condition became a lot less painful once I received PRP in early 2019. (I wrote about this in our regenerative-medicine article.) This treated the tendonitis, but the irritation/mild pain and swelling from the bursa persisted… until quite recently.

Shoe Modification for Runners with Haglund’s Deformity

To be clear, the scientific literature does not yet describe if the bony protrusion/heel bump will resolve or regress if the irritating source (such as a hard-heeled shoe, high-heeled shoe, possibly longstanding insertional Achilles tendonitis, and more) is removed. However, it is anecdotally estimated that 50% of cases of Haglund’s deformity can be treated by removing the aspect of the shoe which is rubbing on the bony protrusion (4). Let’s look at three runners and one soccer player who altered their shoes for Haglund’s deformities (or suspected Haglund’s deformities).

Runner Søren Rasmussen’s shoe modification where he removed the hard, inner plastic of the shoe’s heel, but retained the shoe’s integrity. Image: Søren Rasmussen

Runner Chris Cochrane’s modified shoe. Image: Traileffect.com/2017/05/the-curse-of-pointy-heels-modifying.com

The modified shoe of professional soccer player Philippe Coutinho photographed in 2017. Though Coutinho has never confirmed this, this shoe modification could be to relieve Haglund’s deformity. The next year, in 2018, Coutinho had updated shoes, custom Nike Mercurial Vapor 11’s where the outer liner of the shoe appeared to cover a hole in the harder shoe lining. Image: Anfieldhq.com

Haglund’s deformity and shoe altering for it was also recently discussed on the LetsRun forum. While I’m not sure where one of the commenters ‘Marketing guy’ got that 25% of the population has a Haglund’s deformity, it’s certainly a common problem in runners. I am also surprised there seems to be a total lack of shoes available to accommodate this.

Now, let’s examine before-and-after pictures of the heels of two runners prior to and after removing the hard, plastic heel of their running shoes.

Søren Rasmussen’s heels before (left) and after (right) removing the hard plastic from the back of his right shoe. Following a period of shoe modifications and identification of shoes which did not rub on his bony heel growth, Søren has a less swollen and less painful heel. While his heels don’t appear completely symmetric, he can now run and walk mostly without pain. Søren seems overall happy he did not have surgery done, but denies that his heel feels ‘perfect.’ He is currently able to race at a highly competitive level, but does intermittently get heel pain. Images: Søren Rasmussen

My heel before (left) and then two weeks after (right) modifying my left shoe. I also had a noticeable decrease in the size of my heel and the discomfort I felt in it. Once again, there still appears to be some swelling, but the pain is gone. I ran more than 100 miles the week before I took the ‘after’ image, and I am hopeful that the remaining bursitis/swelling will disappear over time. Certainly my tiny bone spur itself is not the cause of the remaining bump, but the residual thick fluid in the bursa is. Images: Tracy Høeg

Yes, you saw it here first, before in the scientific literature! Shoe alteration helps some runners.

Surgery for Runners with Haglund’s Deformity

Though surgical excision of the bony growth of the calcaneus is only required in resistant cases (20), it seems many athletes are being convinced that surgery is the only valid option. And perhaps it is for some people.

Case Studies of Haglund’s Deformity in Runners

Here are four case studies of runners with Haglund’s deformity and the methods they used to treat it.

Case #1: Gwen Jorgensen

Gwen Jorgensen is a professional distance runner and former triathlete who won the gold medal in triathlon at the 2016 Olympics. Gwen developed heel pain in 2017 that was eventually found to be due to a Haglund’s deformity causing retrocalcaneal bursitis and Achilles tendonitis–also known as Haglund’s syndrome. She was treated successfully for Achilles tendonitis with PRP but as soon as she started training and racing again, the pain came back, this time mostly due to the Haglund’s and bursitis.

In an interview with Rich Roll, she described how Nike made a custom shoe for her with spikes and a larger heel drop. She also stated on her YouTube channel that she liked the shoe because “it doesn’t put as much pressure on my heel.” Unfortunately, the injury didn’t improve and she had surgery–once she found a surgeon who would not cut into her Achilles tendon, but operated on the calcaneus and bursae only (16). This is the Achilles-sparing type of surgery for Haglund’s deformity. To be clear, the previous standard procedure usually involved lifting up part of the Achilles tendon from the bone, debriding (cleaning up) the tendon, and then reattaching it (21). In another YouTube video on her channel, Gwen describes her decision to pursue surgery.

At the time of this article’s writing, Gwen is about five months post-surgery. I reached out to her and she was kind enough to respond in a written message that she was happy she had the surgery, had failed with trying shoe modifications, and was running again.

Case #2: Jenny Hitchings

Jenny Hitchings is a 56-year-old runner on the Sacramento Running Association Elite Team in California. In an interview, she described her experience, “I battled Haglund’s and sore Achilles tendons for a few years. My left was worse in the beginning but I ended up having surgery on my right! I tried everything before resorting to surgery, including physical therapy, massage, bone stimulators, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, electronic muscle stimulation, ultrasound, cutting holes in my shoes, and time off. Nothing gave me relief. The surgery included taking one inch off the heel bone, cleaning up the Achilles and bursae, and PRP. I did no running for 12 weeks. But I may have started too soon and ran an easy 10-mile race and that set me back three more months! I was really out for six months or so. But when I started racing again, I have never had heel or Achilles issues again.”

Case #3: Rob Krar

Ultrarunner Rob Krar was also diagnosed with Haglund’s deformity on both heels after an intense period of training and racing in 2009. He underwent the recommended surgery on both heels in April of 2010 and took about two years away from running before he fully recovered. He went on to win the Western States 100 twice in 2014 and 2015 and much more. I was thrilled to speak with Rob for this article.

Rob Krar on his way to winning the 2015 Western States 100 after recovering from surgery for Haglund’s deformity on both of his heels. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

iRunFar: How long did you have Haglund’s symptoms before your diagnosis?

Rob Krar: It’s hard to remember exactly when the symptoms began. My feet in general had been troublesome since 2007, and working 10-hour graveyard shifts while standing on my feet [in my previous career] didn’t help. My symptoms were quite severe from January to August of 2009 when I was training for the TransRockies Run (TRR). I trained and raced TRR with a compensated stride and pinched my sciatic nerve just a half mile from the finish after six days and 120 miles of running. I couldn’t run again until January of 2010, and even after four months away from running, the pain was worse. The bumps on my heels were just as big, if not bigger, and it hurt to even walk or hike. Ultimately both my heels were just as bad and I had surgery on both at the same time.

iRunFar: Did you find out what caused your Haglund’s?

Krar: No. The Haglund’s seems to remain a bit of a mystery, at least in my experience.

iRunFar: Did you try modifying your shoes to accommodate the deformities before surgery?

Krar: Not to try and resolve the issue. Once they were there, they weren’t going away. I tried cutting holes in the back of a few shoes to relieve the pressure with mixed results.

iRunFar: Do you know what type of surgery you had? Was it Achilles-sparing?

Krar: My surgery was Achilles-sparing, although my surgeon had my permission to detach my Achilles if he felt it was the best option once he was in there and had a better look. Interestingly, I’d never heard of Haglund’s until I had it, but since then it seems to be more and more common. I’ve had countless inquiries from others asking for my thoughts.

iRunFar: What happened after the surgery, in your recovery?

Krar: My surgeon told me to expect a year of recovery before running comfortably again. Like many impatient runners, I rushed that timeline and tried running about three months after surgery. It was a terrible idea. I set my recovery back and ultimately gave up the idea of ever running, let alone racing, again. I was not a model of perseverance and determination at the time and at times the frustration was overwhelming.

It wasn’t until May of 2011 (13 months post-surgery) that I started running some short and slow runs with my wife and that I realized the pain had subsided and I could get back out on the trails. It was a balancing act though, too much speed or distance and I’d be out a couple days letting my heels settle down. The rest of 2011 was more of the same and I’d still not entertained any idea of returning to training and racing.

The winter of 2011/2012 was the turnaround for me. I didn’t run a step, but logged huge vertical while ski mountaineering, unknowingly getting myself into ridiculously good shape. I jumped into the Moab Red Hot 33k in February (22 months post-surgery) with no running under my legs. I won the race and felt great. From that point on, my heels were mostly good to go and I dove head first back into significant training and racing with only a few mild and short flare-ups.

I think the point is that although each individual is different, from the Haglund’s surgery folks I’ve spoken to, nearly everyone has the same story, including myself: have surgery, come back too soon, and set yourself back. The difference is those who completely walk away for some time seem to succeed the most in returning to full competitiveness and those who continue to play the cat-and-mouse game end up walking away for good.

These days when I’m in my heaviest training phases, my heels still ache and I have to nurse them along, but they don’t get in the way of racing to my potential. I have little doubt now, nine years post-surgery, that it was the best decision for me at that time.

Case #4: Tracy Høeg (the Author)

Wrapping up with my own experience, I have had a very similar course to Gwen Jorgensen, prior to her surgery. I’ve had swelling and pain in my posterior heel since 2013, which would initially come and go and then just would not go away starting a little over a year ago. It seemed to only partially respond to eccentric calf loading (heel lowerings).

After the New Year’s Resolution Race in Auburn in January of 2019, I had a worsening of my heel pain and did a high-resolution ultrasound on my Achilles tendon. I could clearly see a bone spur, diffuse Achilles tendonitis around a tear, and increased fluid volume in my retrocalcaneal bursa. I had the previously mentioned PRP treatment to my Achilles. Three months later, the pain was better, but the swelling was still there, albeit less, and my tendon mechanics were still off. I rescanned my tendon and indeed saw resolution of the tendonitis and tear, but the bone spur and retrocalcaneal bursitis remained.

My coworker attempted to aspirate the fluid out of my bursa, but it was actually a gel-like substance which was too thick to suck out even with a large-bore needle. Ouch! My interpretation of this is that it was previously very swollen and filled with fluid. As the fluid leaked out and the inflammation resolved, inflammatory cells remained in the bursa and created this gel. This is likely why people retain a sizable bump on their heel long after the active inflammation is gone. Whether this bump affects Achilles function, I do not know.

Then something really lucky happened: I got a blister on my heel from new running shoes. This led me to cut a hole in the heel of my normal running shoes which allowed me to run without heel pain. After now seeming to be able to run endless miles, I find myself wondering how many other runners with Haglund’s deformity/a calcaneal bone spur could also benefit from a running-shoe plastitectomy rather than an invasive surgery. I also find myself wondering where I can buy a pair or two of heel-less running shoes. I suspect that whether or not shoe modifications will be successful depends on the location and size of the heel deformity, the shoe type, and the type of modification done to the shoe.

Final Thoughts on Haglund’s Deformity

When is surgery indicated for Haglund’s? When can a much simpler shoe modification be done instead? How can this condition be prevented? I am ending with perhaps more questions than answers, but I hope this article will bring attention to and conversation about a common, often devastating, and poorly understood condition.

Call for Comments

Have you suffered from or do you suffer from Haglund’s deformity or syndrome? Have you had success with any treatment? We would love to hear your story.

References

- Ahmed I. M., Lagopoulos M., McConnell P., Soames R. W., Sefton G. K. Blood supply of the Achilles tendon. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1998;16(5):591–596. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160511.

- Alfredson H, Cook J. A treatment algorithm for managing Achilles tendinopathy: new treatment options. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(4):211–216. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.035543

- Boesen AP et al. Effect of high-volume injection, platelet-rich plasma and sham treatment in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: and randomized double-blinded prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2017; 45(9):2034-2043.

- Haglund’s Deformity Net. “Haglund’s Deformity Symptoms and 4 Ways of Treatment”. Haglundsdeformity.net. Accessed 10/12/19.

- Hatch, D. Achilles Tendonitis. Ortho Bullets. https://www.orthobullets.com/foot-and-ankle/7022/Achilles-tendonitis. Updated 2/17/19.

- Komi P V. Relevance of in vivo force measurements to human biomechanics. J Biomech. 1990;23: 23–34.

- Komi P, Fukashiro S, Järvinen M. Biomechanical loading of Achilles tendon during normal locomotion. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11: 521–31.

- Ling Y, Wang S. Effects of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(37):e12110.

- Lohrer H. Die Achillodynie—Eine Übersicht. Medizin Tech. 2006;7: 34–41.

- Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC. Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy. Clin Sports Med 2003;22:675–92.

- Monteagudo M, de Albornoz PM, Gutierrez B, Tabuenca J, Álvarez I. Plantar fasciopathy: A current concepts review. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(8):485–493. Published 2018 Aug 29.

- Moore K and Dalley A. Clinically oriented anatomy. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins. 1999.

- O’Neill S, Watson PJ, Barry S. Why are Eccentric Exercises Effective for Achilles Tendinopathy?. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(4):552–562.

- Shetty SH, Dhond A, Arora M, Deore S. Platelet-rich plasma has better long-term results than corticosteroids or placebo for chronic plantar fasciitis: randomized control trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58:42–46.

- Rathleff, M. S., Mølgaard, C. M., Fredberg, U. , Kaalund, S. , Andersen, K. B., Jensen, T. T., Aaskov, S. and Olesen, J. L. (2015), HL strength training and plantar fasciitis. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 25: e292-e300.

- Roll R and Jorgensen G. “Gwen Jorgensen’s Champion Mindset.” (https://www.richroll.com/podcast/gwen-jorgensen-462/). Episode 462. 8/21/19

- Sobhani S, Dekker R, Postema K, Dijkstra PU. Epidemiology of ankle and foot overuse injuries in sports: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports2013;23:669–686.

- Tatli YZ, Kapasi S. The real risks of steroid injection for plantar fasciitis, with a review of conservative therapies. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2(1):3–9.

- Tu P. Heel Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018 Jan 15;97(2):86-93.

- Vaishya R, Agarwal AK, Azizi AT, Vijay V. Haglund’s Syndrome: A Commonly Seen Mysterious Condition. Cureus. 2016;8(10):e820. Published 2016 Oct 7. doi:10.7759/cureus.820.

- Xu, JH, et al. Modified Bunnell suture expands the the surgical indication of the treatment of Haglund’s syndrome heel pain with endoscope. Exp Ther Med. 2018 Jun; 15(6): 4817-4821.

- Yi TI, Lee GE, Seo IS, Huh WS, Yoon TH, Kim BR. Clinical characteristics of the causes of plantar heel pain. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35(4):507–513. doi:10.5535/arm.2011.35.4.507

- Zafar M, Mahmood A, Maffulli N. Basic science and clinical aspects of Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2009;17: 190–7.