The National Institutes of Health say that regenerative medicine is “the process of creating living, functional tissues to repair or replace tissue or organ function lost due to age, disease, damage, or congenital defects. This field holds the promise of regenerating damaged tissues and organs in the body by stimulating previously irreparable organs to heal themselves.” Regenerative medicine within sports medicine generally refers to “a strategy whereby the injured site is provided with the raw materials necessary for ‘scarless repair’ or regeneration to occur in situ” (Textor, 2014).

Regenerative sports medicine includes a diverse array of techniques, such as decreasing the inflammation in your body to promote healing, eccentric-strength training to help bring blood flow to damaged tendons, and prolotherapy or sugar injections to stimulate healing. Another technique you may have already heard of is platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections. PRP is a highly concentrated solution of a person’s own platelets and growth factors, which are substances in the blood that can stimulate cell growth and healing, taken from a blood draw and concentrated via centrifuge.

When I started my physical medicine and rehabilitation medical residency in 2015, I was skeptical about the effectiveness of regenerative medicine in the treatment of sports-related injuries. At that time, many scientific articles looking at PRP use for athletic or musculoskeletal injuries were sponsored by medical-device companies trying to sell their platelet-concentrating equipment. In other words, many studies were biased. Also, most studies at that time were not randomized.

Fast forward four years and the evidence for the use of PRP in tendon injuries and arthritis is actually quite robust, including non-sponsored, randomized control trials. There is also rapidly growing evidence for the use of another regenerative-medicine technique, the injection of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC), a concentrate of bone marrow taken from a person’s own bone that is rich in growth factors and platelets, like what’s in PRP, but additionally containing a small fraction of stem cells, cells of great importance in humans because they give rise to many other different kinds of cells in the body. BMAC appears to be just as effective, if not more so, for tendon injuries and arthritis, but also appears much more effective at treating cartilage injuries and injuries of the knee’s anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

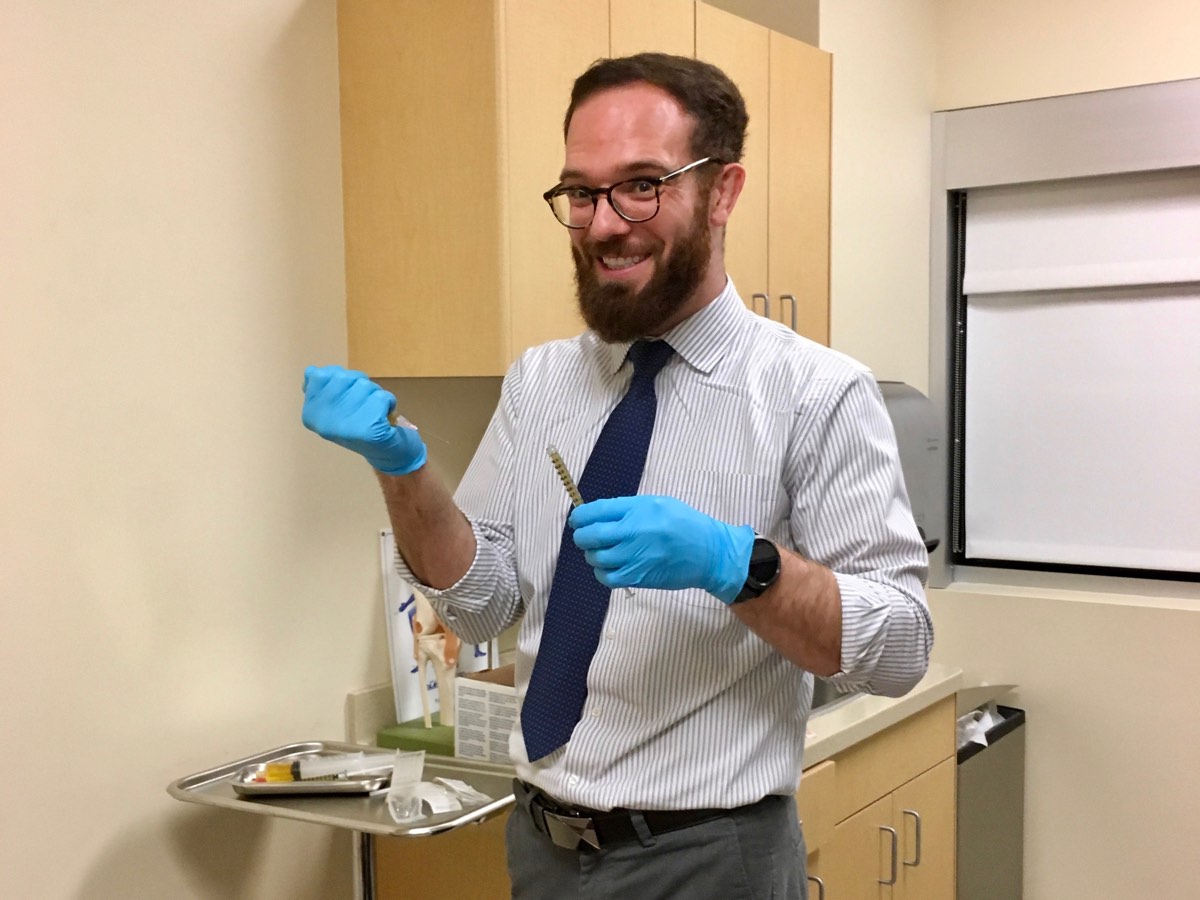

Figure 1. Would you let this guy inject this stuff into your injury? This is a photo of author Dr. Tracy Høeg’s physician colleague holding a vial of her platelet-rich plasma (PRP) which is about to be injected into and around her Achilles tendon. The vial contains a rich concentration of her own blood platelets that are healing her Achilles tendon better than she thought was possible. Image courtesy of Tracy Høeg.

I currently work in a sports-medicine practice in Napa, California called the the Bodor Clinic where we specialize in regenerative medicine and I feel on nearly a daily basis that I work at the modern-day Lourdes. Since I started this job last August, I have been overwhelmed with testimonials of athletes and non-athletes alike who have suffered years of pain and nothing helped until PRP or BMAC. Here are a few examples from runners: PRP to the intervertebral disc totally curing intractable back pain allowing many runners to run again; BMAC to the knee ACL allowing patients to run again; and people running again after PRP to the knee meniscus, the labrum of the hip, and the patellar or Achilles tendons. It is not unusual for patients to cry with joy because, after the treatment, they are running pain free and have avoided surgery. Many of the above-mentioned conditions have historically been very difficult to treat, and surgery is rarely an optimal cure, is invasive, and has associated risks. I am not trying to say that regenerative treatments such as PRP or BMAC work for everyone or everything, but I believe that in the future these treatments will play an even more major role in the treatment of non-healing athletic injuries.

This article focuses on what PRP and BMAC treatments are and how they work, and additionally offers background on certain stem-cell treatments to avoid. In addition, we explore three anecdotal examples of trail runners and ultrarunners who’ve used PRP for injuries: Dr. Megan Roche for a hamstring injury, Dr. John Onate for an Achilles injury, and me for an Achilles injury.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections

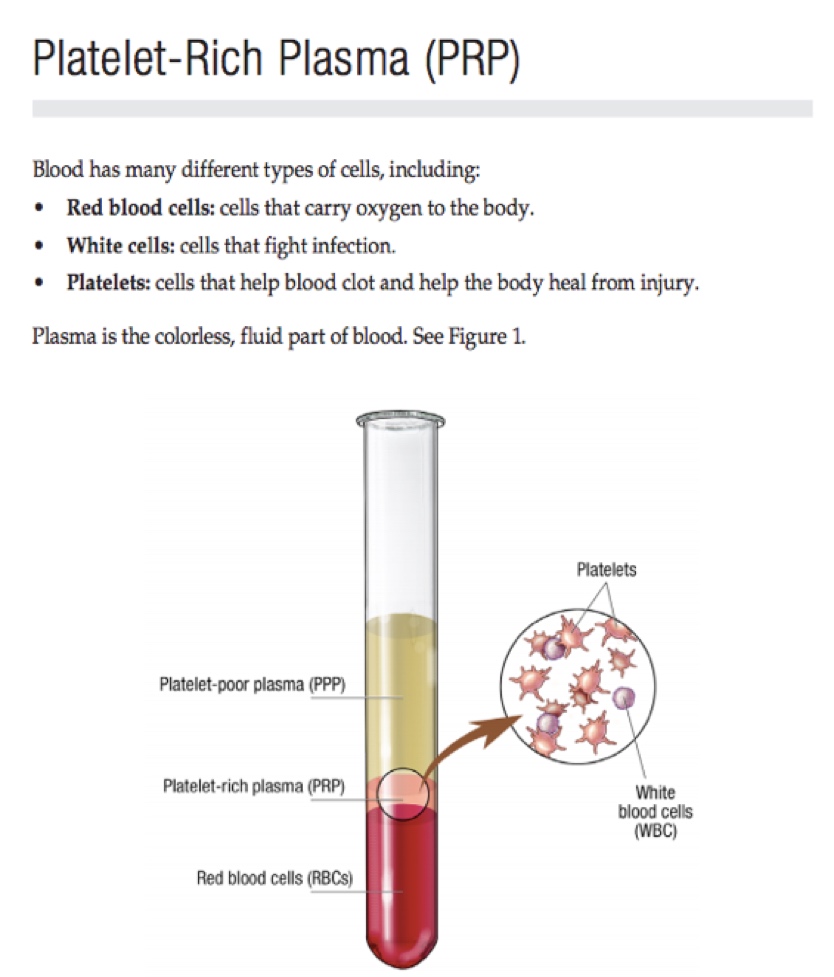

We learned earlier that PRP is a solution made from your own blood. Your blood primarily contains platelets, white and red blood cells, and plasma. Platelets have a lot of proteins, including growth factors. Other factors, such as the glue-like protein called fibrinogen, can be found in plasma. These proteins help control inflammation and heal the body from injury. When you are injured, your body quickly sends platelets to repair the area of injury. They form a clot to help prevent more bleeding. Platelets also help create a foundation for new tissue to grow and release growth factors and other proteins (Foster, 2007).

To obtain PRP, your blood is taken via a blood draw and spun in a centrifuge to remove almost all of the red and (usually) white cells. A concentration in the plasma of at least five times as many platelets as that of normal blood is generally considered PRP (Chahla, 2017; Dhillon, 2012). PRP does not contain stem cells. However, PRP growth factors have been shown to attract, activate, and increase the number of stem cells in the injured area (Nurden, 2011; Qian, 2017). PRP has been used successfully in humans in wound healing since the 1970s (Mei-Dan, 2011). There is also extensive evidence for its use in veterinary medicine.

Figure 2. A description of platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Image courtesy of Mayo.edu/research/documents/regenerative-medicine-patient-education-pamphlet-mc7993/doc-20419433.

The evidence for use of PRP in sports medicine is as follows (Chala, 2019; Boesen 2017):

- PRP has excellent evidence for use in symptomatic mild to moderate osteoarthritis and lateral epicondylitis.

- PRP has good evidence for use in tendinopathies and tendon disorders, plantar fasciitis, ACL injuries, and Achilles tendinopathy (following the Boesen, 2017 randomized controlled trial).

- PRP has emerging evidence for use in meniscus injuries of the knee and intervertebral disc injuries in the back.

PRP is currently being used to treat many conditions that could previously only be treated with surgery, including but not limited to knee-meniscus injuries, hip-labrum injuries, osteoarthritis of the knee, and tears and injuries of intervertebral discs, not to mention rotator-cuff tendinopathy. (Some runners have shoulder problems, too!) PRP should always be done in conjunction with a good physical therapist who can help gauge how quickly and how to return to your previous activities after the procedure. If your current injury is not listed here, it doesn’t mean PRP will be ineffective; it may be that there is currently not enough evidence to mention it.

However, PRP has not been found to be effective in treating muscle strains or injuries and appears to be less effective in treating bony or cartilage defects. Some injuries require more than one PRP injection to be effective and studies are still being done to help determine which injuries those are. A sequence of PRP injections is prescribed more frequently outside of the United States than in the U.S. (Boesen, 2017). As an aside, PRP has also been found to be efficacious in treating infertility, hair loss, skin scarring, and more.

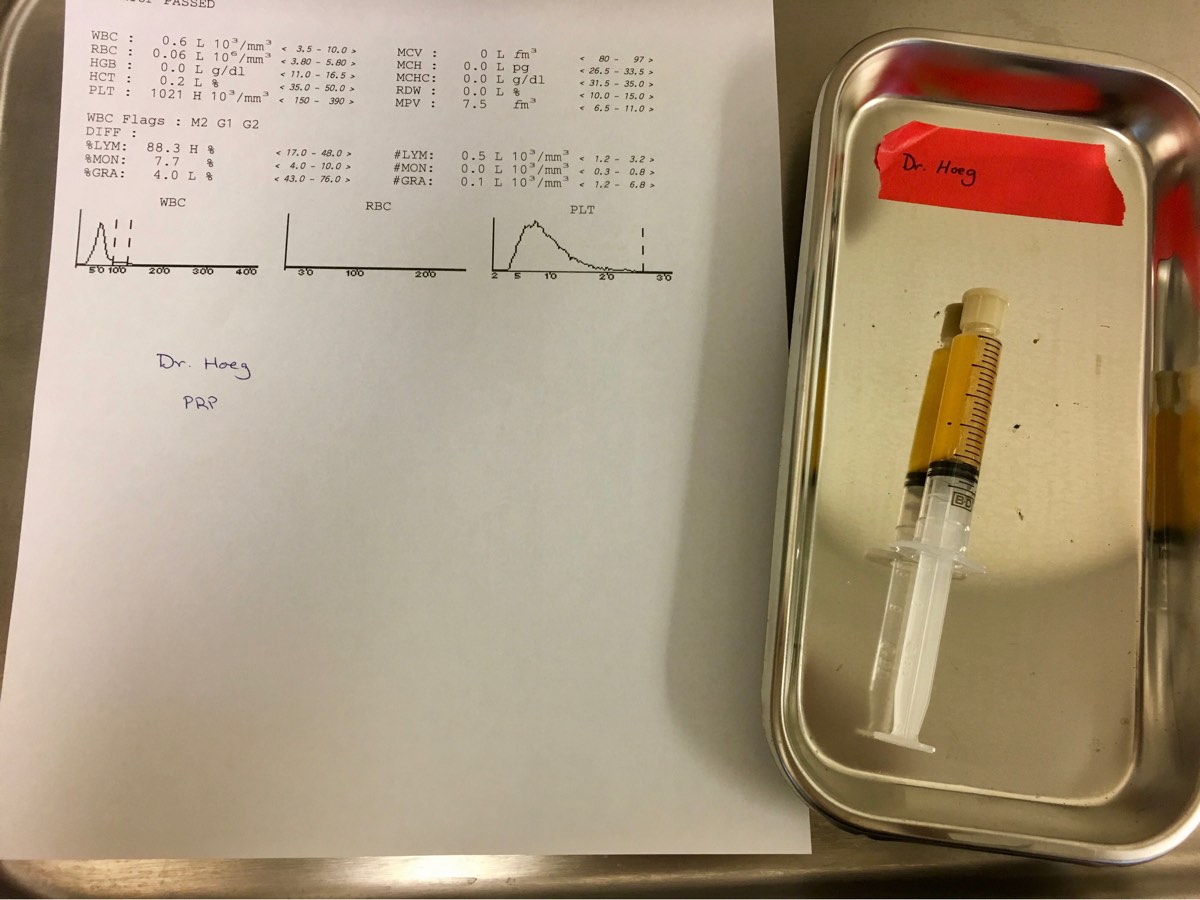

Figure 3. The author’s own PRP. Most of the red and white blood cells have been removed from her blood and there is a very high concentration of platelets, coloring the plasma yellow. This corresponds to the pink ‘PRP’ in Figure 2. The discrepancy in color may be due to the fact that we are able to remove more red and white blood cells with our technique at the Napa Medical Research Foundation/Bodor Clinic.

Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate (BMAC) Injections

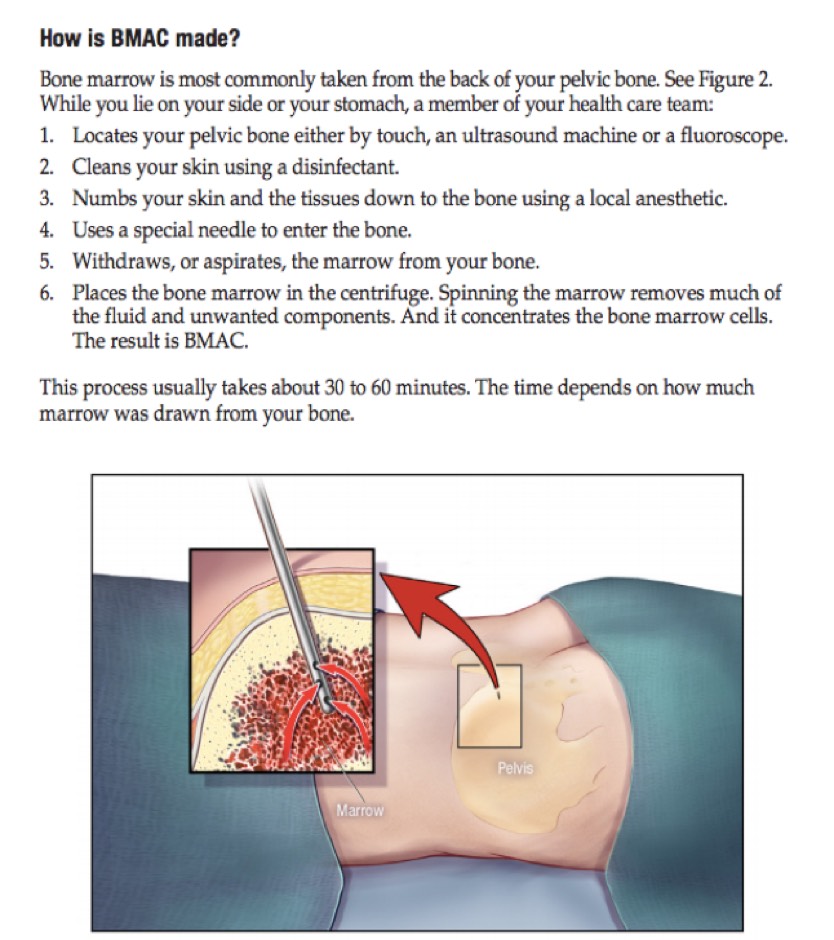

Your bone marrow has mesenchymal, or musculoskeletal system, stem cells (MSCs) and many other cells involved in healing. Bone marrow is the tissue inside your bones that creates your blood cells. Cells found in bone marrow can be used to treat damaged tissue, improve function, and help control pain. BMAC harvesting creates a concentrated form of bone marrow. Compared to usual bone marrow, BMAC has a higher concentration of regenerative cells, including MSCs and growth factors like those found in PRP.

BMAC has the best evidence for use in lesions/injuries, cartilage (Gobbi, 2016), and bone (Hauser, 2013), as well is in ligaments (Centeno, 2018) and tendons (Pascual-Garrido, 2012) (often combined with PRP) (Kim, 2018). One exciting example, which we are studying in our practice and with University of California, Davis, is the use of BMAC injection to tears of knee ACL, helping patients avoid surgical reconstruction and/or persistent instability symptoms. BMAC to the ACL already has some promising preliminary evidence (Kanaya, 2007; Centeno, 2015; Centeno, 2018; Raj, 2018). BMAC has also been found to be safe (Gobbi, 2016; Moatshe, 2017; Centeno, 2015; Cenento, 2018).

Figure 4. The bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) harvesting process. Image courtesy of Mayo.edu/research/documents/regenerative-medicine-patient-education-pamphlet-mc7993/doc-20419433.

Interview with John Onate About PRP Treatment for His Achilles-Tendon Injury

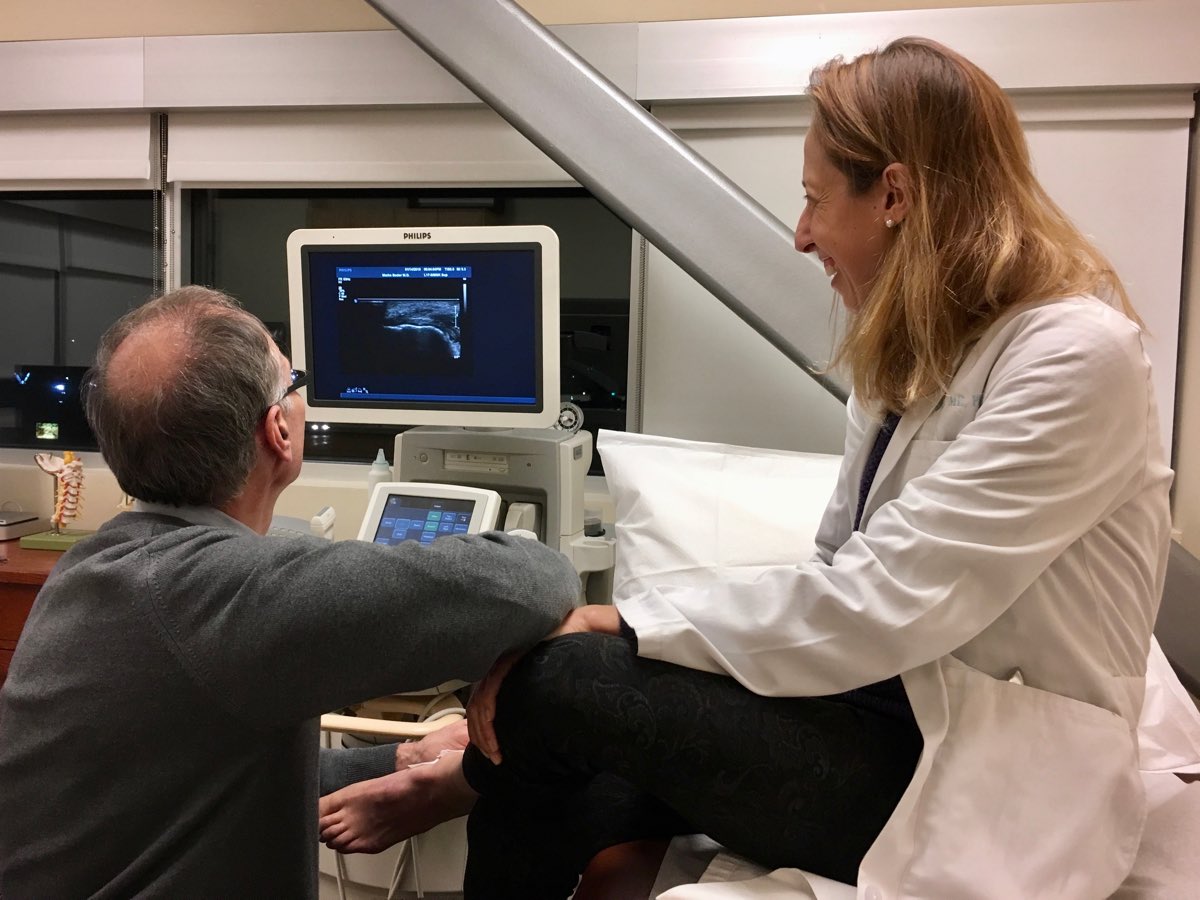

This interview with John Onate, MD is about the PRP treatment he received for an injury in his Achilles tendon. Of note, he was seen at the Bodor Clinic before I started working there. John is an avid trail-ultramarathon runner and a psychiatrist at the University of California, Davis who specializes in mood disorders in endurance athletes.

iRunFar: How long did you have Achilles pain before the PRP injection?

John Onate: Eight-and-a-half months.

iRunFar: Had you tried other treatments that didn’t work? How long had you taken off from running beforehand?

Onate: I took six weeks off initially, but after one run the pain was still there and the tendon was weak with no rebound. I got physical therapy and started eccentric calf stretches, standard protocol. (I worked up to 100 pounds in addition to body weight.) I started running again six more weeks later, but still had some pain on and off for two months and then limped through a 50k. (I do not recommend this rehabilitation plan.) I then took 2.5 months off with no running and took up sport climbing. Then I was evaluated by Dr. Bodor at the Bodor Clinic. On ultrasound, he found two to three lesions on the tendon surface… I was not running at that point but he told me not to stretch for two weeks after the procedure. I then slowly returned to running.

iRunFar: Do you know what specific type of Achilles problem you had? You mentioned lesions, but was it a tear? Tendinosis? Do you know?

Onate: It was classic Achilles tendinosis. There was only pain with running and after eccentric strengthening. (Think heel lifts with weight, but lowering instead of lifting.) The left Achilles was weak and I could not perform a concentric toe raise without support. [Author’s Note: Tendinosis is chronic tendinitis or chronic inflammation of a tendon. Eccentric means the muscle is lengthened when strengthened and concentric means the muscle is shortened when strengthened. For example, a heel raise is concentric and a heel lowering is eccentric.]

iRunFar: After the PRP injection, when did the pain go away and when did you return to running? Could you describe the series of events you went through before returning to running? Did you go through any period of immobilization?

Onate: The worst pain and swelling was the 2.5 days after the injection, to be honest. I could barely walk for 24 hours after and, if I could do it over, I would have used a CAM boot. However, three days after the injection, the pain decreased over a 12-hour period to basically zero. I started running after two weeks with some tightness but the tendon itself was significantly improved functionally and soon I was back to tolerating 50 miles a week. I ran a 50k fun run 2.5 months after PRP, a 50k race 4.5 months later, and after that 67 miles of a 100-mile race from which I dropped because of heat and fueling issues. I ran a solid Quad Dipsea seven months post-PRP with no Achilles issues. [Author’s Note: A CAM boot is a controlled-ankle-motion walking boot used to take pressure off an injured ankle or foot.]

iRunFar: Has your problem come back? Is it still lingering?

Onate: Knock on wood… the problem has not come back.

iRunFar: Do you continue to do eccentric-loading exercises?

Onate: Yes, I do slow concentric-to-eccentric calf raises, both legs, most days of the week before a run (body weight only). I also have taken up sport climbing that I think has helped as well. I think hip mobility and lack of gluteal strength contributed to the injury, and I like climbing because it cues hip mobility and glutes during the activity.

iRunFar: If you had to do it over, would you get the PRP injection again?

Onate: Yes, and in retrospect I think I would have gotten the evaluation after the first eight weeks of physical therapy did not resolve the issue.

Interview with Megan Roche About PRP Treatment for Her Hamstring-Tendon Injury

Megan Roche, physician runner, running coach at Some Work All Play (SWAP), and Stanford Sports Medicine researcher received a PRP injection for a hamstring-tendon injury about 7.5 weeks ago–and six weeks before this interview.

iRunFar: What sort of injury did you have and for how long did you have it? And how did you get a diagnosis?

Megan Roche: I had an acute high hamstring tear or chronic high hamstring tendinopathy. I’ve had the high hamstring tendinopathy on and off for the last year and the acute high hamstring tear for the last 16 weeks. I got an MRI for the diagnosis after the high hamstring tear. The underlying tendinopathy likely put me at higher risk for the tear.

iRunFar: What had you tried in your recovery process before PRP?

Roche: I tried just about everything before PRP! About a year ago I had a cortisone injection into my ischial bursa, which resolved the pain for some time. In the last 16 weeks, I’ve done physical therapy, massage therapy, ROLFing, acupuncture, and chiropractic adjustments. [Author’s Note: The ischial bursa is area on the ‘butt bone’ around the start of the hamstring tendon.]

iRunFar: What made you decide to get PRP?

Roche: I finally resorted to PRP because I had exhausted all of my therapy options and still wasn’t seeing any hamstring progress. The evidence on PRP for improving outcomes in hamstring tendinopathy/tears is mixed, but I’ve seen many clinical cases of hamstring improvement following PRP and was willing to make the leap given that I had exhausted all other options.

iRunFar: What was the PRP experience like for you and where were you treated?

Roche: I got PRP at a local family practice in Colorado. My blood was drawn in office, centrifuged, and then injected into my hamstring tendon with ultrasound guidance. In addition, percutaneous needle fenestration was performed, which essentially means using the PRP needle to poke tiny holes in the tendon to facilitate added blood flow and healing. There are many different ways that PRP can be performed with differences in ultrasound use, fenestration, and blood preparation (such as high or low white-blood-cell count, for example), and it’s important to research these variables in your particular injury site and inquire about the PRP process with your doctor before deciding to have the procedure. [Author’s Note: In an ideal world, your doctor will be able to educate you on whether or not to put holes in the tendon and what type of PRP preparation to use.]

iRunFar: Describe your recovery process after PRP and how you decided when to start using which different workout modalities, strength training, and then running. What evidence/advice did you base this on or did you go by feel?

Roche: I took 10 days totally off of lower-body exercise after PRP. I lifted weights with my upper body, but was careful not to engage the lower body and avoided exercises like planks and push-ups. From there, I worked into gentle hamstring range of motion, followed by concentric exercises, followed by eccentric exercises over the next few weeks. At two weeks I started light biking and gradually worked up to more bike workouts at three weeks. There are many different protocols online outlining the return to run post-PRP and that plan can vary based on injury location. My doctor cleared me to run gently at four weeks and I tried some short runs, but I ultimately decided to give it the recommended full six weeks before returning back to running.

iRunFar: When did you return to running, how did it feel when you did, and how long would you run at once?

Roche: Initially, I started with just mixing in some running on hikes, running for 30 seconds, five to 10 times. From there, I progressively worked into 15- to 20-minute runs. At that point, I decided to give my hamstring the full six weeks because I didn’t feel comfortable with the faster progression and so I haven’t returned back to running yet.

iRunFar: Have you had any problems with your hamstring since then?

Roche: My hamstring still does not feel 100% and has lingering pain and tightness. A lot of this involves sorting through the kinks and continuing to get stronger with physical therapy given that the tear has likely healed at this point. I know I will have to work through some initial pain as I return to run and finding that balance and comfort level in the return to run will probably be the most difficult part of the whole injury.

iRunFar: Would you do it again?

Roche: I would get PRP again. I had exhausted all other resources outside of surgery when I got PRP and so I was willing to make a leap. For me, the biggest downside was the cost (my insurance does not cover PRP) and the break I had to take from cross training. I did get a psychological boost from PRP knowing that I was giving my hamstring the best healing factors that I could and that I was trying all options.

iRunFar: Is there any evidence you have that PRP worked better than extended rest and then the gradual return to running that you went through after PRP?

Roche: I was definitely stronger in my physical-therapy exercises after getting PRP, but honestly did not feel a difference in how my hamstring felt running at the four-week mark. It’s tough to say whether that strength boost is from PRP or simply from time and the extended period of full rest. But psychologically, I’m happy to know that I’m giving the hamstring added healing factors.

[Editor’s Note: Not long after this interview and article were published, Megan Roche re-injured her hamstring after returning to running post-PRP treatment. She reportedly stepped in a hole while trail running and tore the soft tissue again. Shortly thereafter she underwent surgery.]

The Author’s PRP Experience for Her Achilles-Tendon Injury

Based on some truly amazing recovery stories in our own clinic, the randomized controlled trial by Boesen from 2017, and John Onate’s experience, I recently and finally decided to try PRP for my own Achilles injury. Since 2013 I had dealt with it, what was at first a little, painful bump on my heel. Initially, with rest from running, it would tend to resolve. But whenever I picked up my hill/mountain training, it returned. After one particularly arduous run on the Western States Trail in 2017, it really started to bother me. Later that day I learned about eccentric-tendon loading and how I could use heel lowerings per the Alfredson protocol (Alfredson, 1998) to stimulate tendon repair. Alfredson was a Swedish runner who was so sick of his Achilles hurting that he attempted to break it with more and more weight on his back in a backpack and performing repeated eccentric lowering heel exercises. He wanted to break it so a surgeon he knew would operate on it. Though he failed to break it, his pain went away.

I always remind my patients that this is the first step in regenerative medicine (aside from eating a low-inflammation diet) in treating a tendinopathy: increasing blood flow to the injured tendon. This can be accomplished by eccentric loading (and really with any progressive mechanical-loading program). Eccentric loading kept my Achilles pain at bay for 1.5 years. The bump on my heel grew but it never really hurt.

Then I ran the California International Marathon and my foot went entirely numb for the last three to four miles. It took me forever to figure out that my Achilles injury with all of its swelling was compressing a nerve at my ankle, which provides sensation to the bottom of the foot. But this too resolved and it was when I was running the Foresthill Divide Loop race in the winter of 2018 and suddenly turned from running downhill to a steep uphill that I felt the dreaded ‘pop’ and the feeling that my calf stopped working. I finished the race, but after that day, everything in my running changed. I still managed to run on it in the 2018 World Long Distance Mountain Running Championships in Poland, but you know we runners can be a crazy breed.

My diagnosis was a small Achilles tendon tear, insertional bone spur, Achilles tendonitis, and retrocalcaneal bursitis. This was all diagnosed from my ultrasound at work.

Figure 8. The author demonstrating with high-resolution ultrasound a small calcaneal spur with surrounding retrocalcaneal bursisits and medial Achilles tendonitis. Image courtesy of Tracy Høeg.

Following the race in Poland last summer, it took me six months, including two months off running and lots of eccentric exercises, to realize this is not going to go away with conservative measures. I was able to run, but recovery took so long and I could no longer walk without pain. I could not dorsiflex, or bend back, my ankle more than five degrees and zero degrees with my knee bent! Most importantly, I couldn’t play soccer with my kids.

Thirty days ago, I drew my own blood, about 45 milliliters to obtain four milliliters of PRP. Dr. Bodor injected the PRP in multiple places in the Achilles region, including into the tear, around the bone spur, in the retrocalcaneal bursa, and into the Achilles tendon mid-substance.

Figure 9. The author drawing her own blood for PRP. Drawing your own blood is not mandatory or expected ;-D. Image courtesy of Tracy Høeg.

Figure 10. Dr. Bodor injecting the PRP in multiple places in the author’s Achilles region. Image courtesy of Tracy Høeg.

For three to four days after the PRP, I was in quite a bit of pain. I was able to do the elliptical if my left foot did not have any more than toe-touch weight on it. Then I used a pretty progressive return to activities and then running protocol based on Boesen, 2017:

- Rest with range of motion exercises for 72 hours.

- Light to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise with tendon loading, letting pain be my guide. I cycled and swam as long as it was pain free.

- After four to five days, begin eccentric-loading program of gastrocnemius (heel lowerings with straight but not locked knee) and soleus (heel lowerings with bent knee) muscles, which can be painful (and it was).

- At 10 to 14 days, begin gradual return to running. And I mean really gradual, like five minutes at a time at first. I was committed to all running being pain free. At first I ran two miles at day 11 and then two miles at day 15. At 22 days post-PRP, I ran 10 miles completely pain free. At four weeks post-PRP, I am up to four days of running per week on the treadmill entirely pain free.

- I should also add I am still completely avoiding stretching the Achilles, and I miss my hot-yoga classes!

Looking with the ultrasound, the tear and bone spur are not visible anymore, but I am not sure if this is because there is so much less surrounding fluid that we can’t see them. My ankle has nearly the same range of motion as my right and the ‘springiness’ has returned to my Achilles tendon.

Figure 11. The bottom photo is the author’s ankles pre-PRP and the upper photo is two weeks post-PRP. The swelling has continued to decrease since then. Image courtesy of Tracy Høeg.

What are the Downsides of PRP and BMAC Treatments?

- Usually they are not covered by insurance. But I have had numerous worker’s compensation insurances cover PRP, Blue Shield covered it once, Kaiser reportedly now covers it for lateral epicondylitis, and I had worker’s compensation cover BMAC once. BMAC tends to cost about three times what PRP does, an average of $1,000 for PRP and $3,000 for BMAC. BMAC is also more invasive as it requires bone-marrow removal.

- Your pain will get worse before it gets better. This is because the injection actually creates a good type of inflammation that stimulates your body’s own healing processes. You can expect your pain be more than it was before the injection for at least three to four days and up to a week.

- For both PRP and BMAC, you should abstain from taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, Aleve, and Advil for one week prior to and six weeks following treatment so as to not interfere with the blood flow to the injured area. In general, NSAIDs impair musculoskeletal healing and should be avoided when one is injured (but this is an entirely different topic).

- The healing process can be slow. Some people feel better in weeks and others in months. This is highly variable.

- Some people do not respond at all and it is not fully understood why this is. In terms of treating tendinopathy, failure to use the muscle at all following the PRP has been shown to result in PRP failure. When the muscle attached to the treated tendon is not allowed to work at all, the PRP has absolutely no effect (Virchenko, 2006). Also younger patients have higher concentrations of growth factors in their platelets making them potentially more likely to respond; this is what is theorized currently though there are no high-quality studies that prove this. Finally, if one has not responded, it is possible that the source of the pain is different than what was diagnosed or treated.

What to Avoid: Let’s Talk About Stem Cells

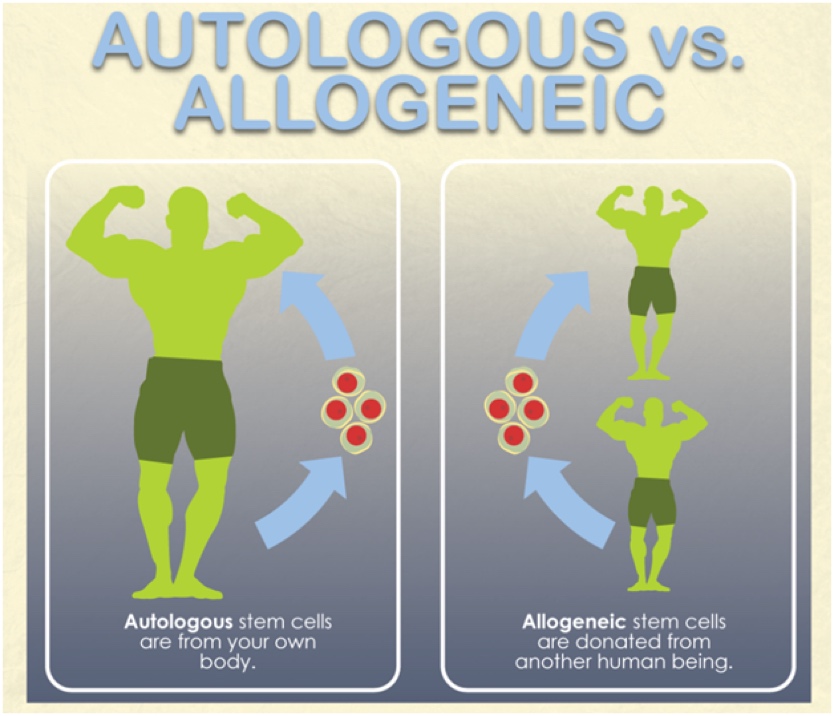

As we’ve talked about, stem cells are important components of BMAC, but not all ‘stem-cell injections’ are alike. Autologous stem cells come from your own body while allogeneic stem cells come from a donor. Bottom line, do not use stem cells from another person to treat your running injury or arthritis. This usage is risky, not backed by research, and, for good reason, not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Allogeneic stem cells are not currently used in sports-medicine practices.

Figure 12. Autologous (from your own body) versus allogeneic (from a donor) stem cells. Regenerative sports-medicine therapies are currently autologous. Image courtesy of Plasticsurgery.org/Images/Blog/autologous-vs-allogeneic.png.

Sadly, a number of scam ‘stem-cell clinics’ in the U.S. sell injections from umbilical-cord blood for problems like knee arthritis. Research (see these two links) has shown that these off-the-shelf stem-cell bottles do not actually contain living stem cells. These concoctions of supposed stem cells are also dangerous. Last December, the New York Times reported on 12 patients being hospitalized with infections after receiving injections of umbilical-cord blood supposedly containing stem cells.

Conclusion

All running injuries have different evidence of rates of success with PRP and BMAC and many conditions have yet to be studied in a systematic way. There is also quite a variety in recovery protocols. If I went into detail about all of these, I would have to write a book rather than an article. It is thus critical that you work with a physician who makes the correct diagnosis, knows the literature on regenerative treatment for your injury, and can provide proper advice on and refer you to a knowledgeable physical therapist for recovery from these treatments.

Finally, be your own advocate. If you have any injury or arthritis, look into the research done in regenerative medicine for your condition. If you don’t have a diagnosis, get one. If your doctor does not provide regenerative-medicine treatments, consider getting a referral to someone who does. This may get you back running again or save you a trip to the operating room.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you used PRP or BMAC treatment for a running-related or other injury?

- If so, can you share your anecdotal experience? We’re interesting in hearing about your diagnosis, how long you were injured prior to the PRP/BMAC treatment, what other therapies you tried before PRP/BMAC, what the PRP/BMAC treatment was like and how it was carried out, and what the immediate recovery and the longer-term return-to-running processes were like for you.

Disclosures

Dr. Tracy Høeg, this article’s author, is employed by the Bodor Clinic and the Napa Medical Research Foundation, which both have a regenerative-medicine focus. However, Dr. Høeg does not receive additional payment or salary for encouraging patients to seek PRP or BMAC in her own clinic or elsewhere.

References

Berkowitz & Miller. Glioproliferative Lesion of the Spinal Cord as a Complication of “Stem-Cell Tourism” N Engl J Med 2016; 375:196-198

Boesen, A.P., Hansen, R., Boesen, M.I., Malliaras, P., and Langberg, H. Effect of high-volume injection, platelet-rich plasma, and sham treatment in chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: A randomized double-blinded prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2017; 45: 2034–2043

Centeno C, Markle J, Dodson E, et al. Symptomatic anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow concentrate and platelet products: a non-controlled registry study. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):246. Published 2018 Sep 3. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1623-3.

Centeno CJ, Pitts J, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman MD. Anterior cruciate ligament tears treated with percutaneous injection of autologous bone marrow nucleated cells: a case series. J Pain Res. 2015;8:437–447.

Chala J & Dallo, I. Biologics in Sports Medicine. Oral Presentation. 1/21/2019.

Gobbi A, Whyte G P. One-stage cartilage repair using a hyaluronic acid-based scaffold with activated bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells compared with microfracture: Five-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2016; 44(11): 2846–54.

Hauser R A, Orlofsky A. Regenerative injection therapy with whole bone marrow aspirate for degenerative joint disease: A case series. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 6: 65–72.

Kanaya A, Deie M, Adachi N, Nishimori M, Yanada S, Ochi M. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells in partially torn anterior cruciate ligaments in a rat model. Arthroscopy (2007) 23:610–7.10.1016/j.arthro.2007.01.013

Kim SJ, Kim EK, Kim SJ, Song DH. Effects of bone marrow aspirate concentrate and platelet-rich plasma on patients with partial tear of the rotator cuff tendon. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13(1):1. Published 2018 Jan 3. doi:10.1186/s13018-017-0693-x

Moatshe G, Morris ER, Cinque ME, et al. Biological treatment of the knee with platelet-rich plasma or bone marrow aspirate concentrates. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(6):670-674.

Mei-Dan O, Laver L, Nyska M, Mann G. Platelet rich plasma—a new biotechnology for treatment of sports injuries. Harefuah. 2011;150:453–7.

Nurden AT. Platelets, inflammation and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(Suppl 1):13–33. doi: 10.1160/THS10-11-0720.

Pascual-Garrido C, Rolón A, Makino A. Treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy with autologous bone marrow stem cells: a 5-year-followup. Stem Cells Int 2012; 1–5.

Qian Y, Han Q, Chen W, et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Derived Growth Factors Contribute to Stem Cell Differentiation in Musculoskeletal Regeneration. Front Chem. 2017;5:89. Published 2017 Oct 31. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00089

Raj M, Khan J, Suarez D, Bodor M. Full Thickness Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair with Autologous Stem Cells. Poster Presentation. American Academy of PM&R. October, 2018.

Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med 2002; Apr;36(2):95–101

Virchenko O, Aspenberg P (2006). How can one platelet injection after tendon injury lead to a stronger tendon after 4 weeks? Interplay between early regeneration and mechanical stimulation. Acta Ortho 77(5): 806-812.

Zhang L, Chen S, Chang P, Bao N, Yang C, Ti Y, et al. Harmful effects of leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma on rabbit tendon stem cells in vitro. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(8):1941–1951.

Zhang J Y, Fabricant P D, Ishmael C R, Wang J C, Petrigliano F A, Jones K J. Utilization of platelet-rich plasma for musculoskeletal injuries: An analysis of current treatment trends in the United States. Orthop J Sports Med 2016; 4 (12): 2325967116676241