I see back pain every day in my sports, spine, and regenerative-medicine practice. I also see runners almost every day. However, rarely do the two overlap. Eighty percent of the general population will experience significant back pain at some point. There are numerous reasons runners experience less back pain than the general population, including:

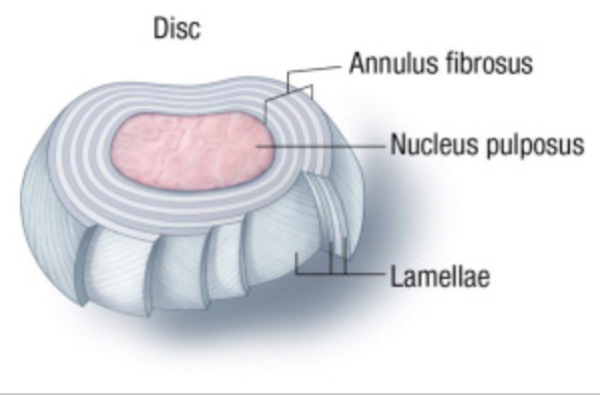

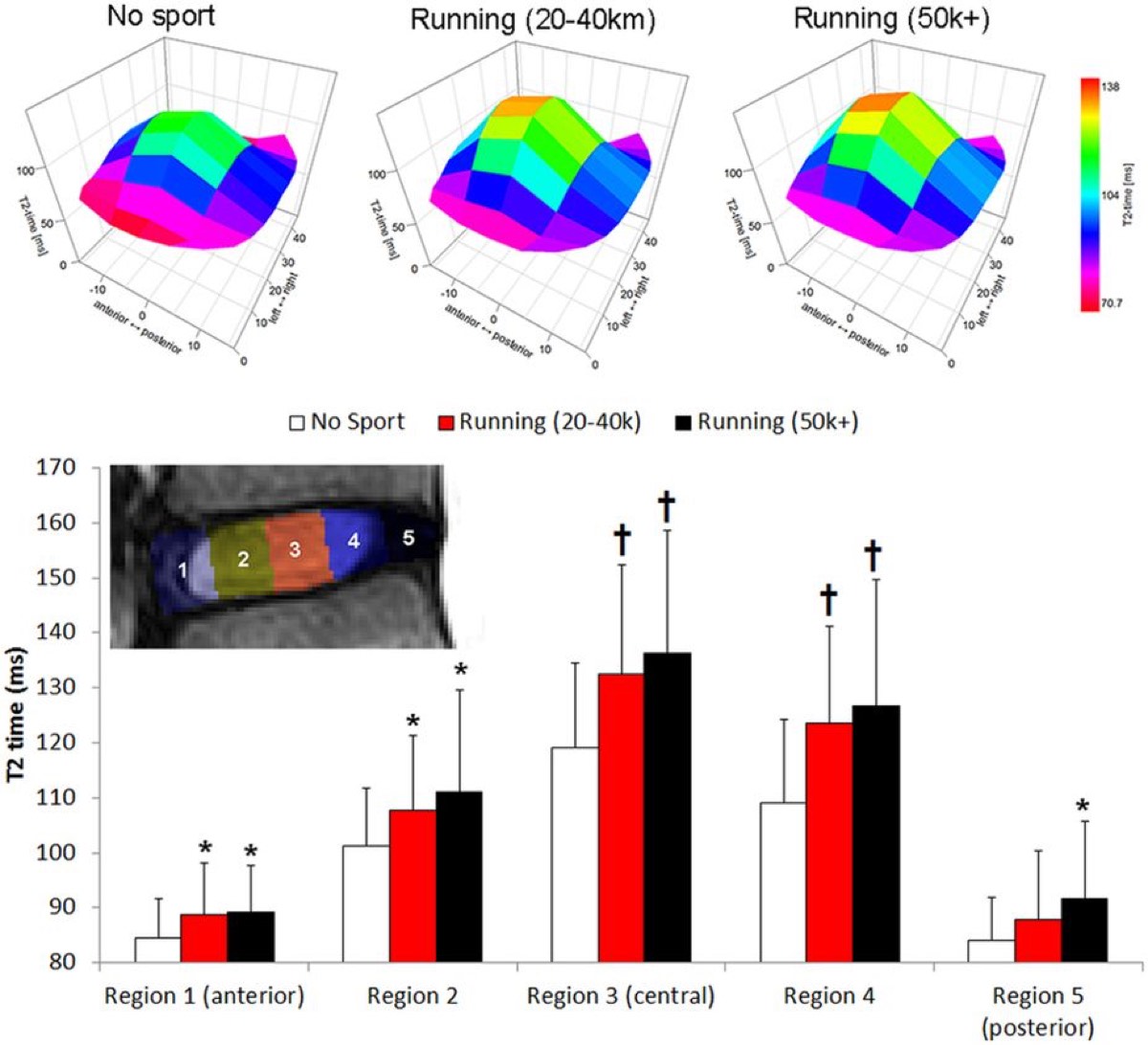

- Running improves intervertebral-disc (the soft tissue between each vertebra in the spine that holds the spine in place, allows for small spinal movements, and absorbs spinal shock and loading) composition in rats (2), dogs (19), and humans (1).

- Running increases blood and nutrient flow to the back’s soft tissues, which facilitates a more rapid healing process (6) and reduces the stiffness that can lead to back pain (6).

- Running increases VO2max (the maximum amount of oxygen we can intake) and a higher VO2max is associated with less back pain (18).

- The endorphins produced when running decrease pain sensitivity (11).

- Running is done in a neutral-spine position and is therefore unlike sports which require significant torque on the spine–like golf and tennis–or holding a weight load while the spine is flexed–such as lifting and rowing.

A graphic demonstration of how regular running tends to improve the intervertebral disc height and composition. Greater T2 times indicate better disc hydration and glycosaminoglycan content, which strengthens the disc. Image: Belavy, 2017 (1)

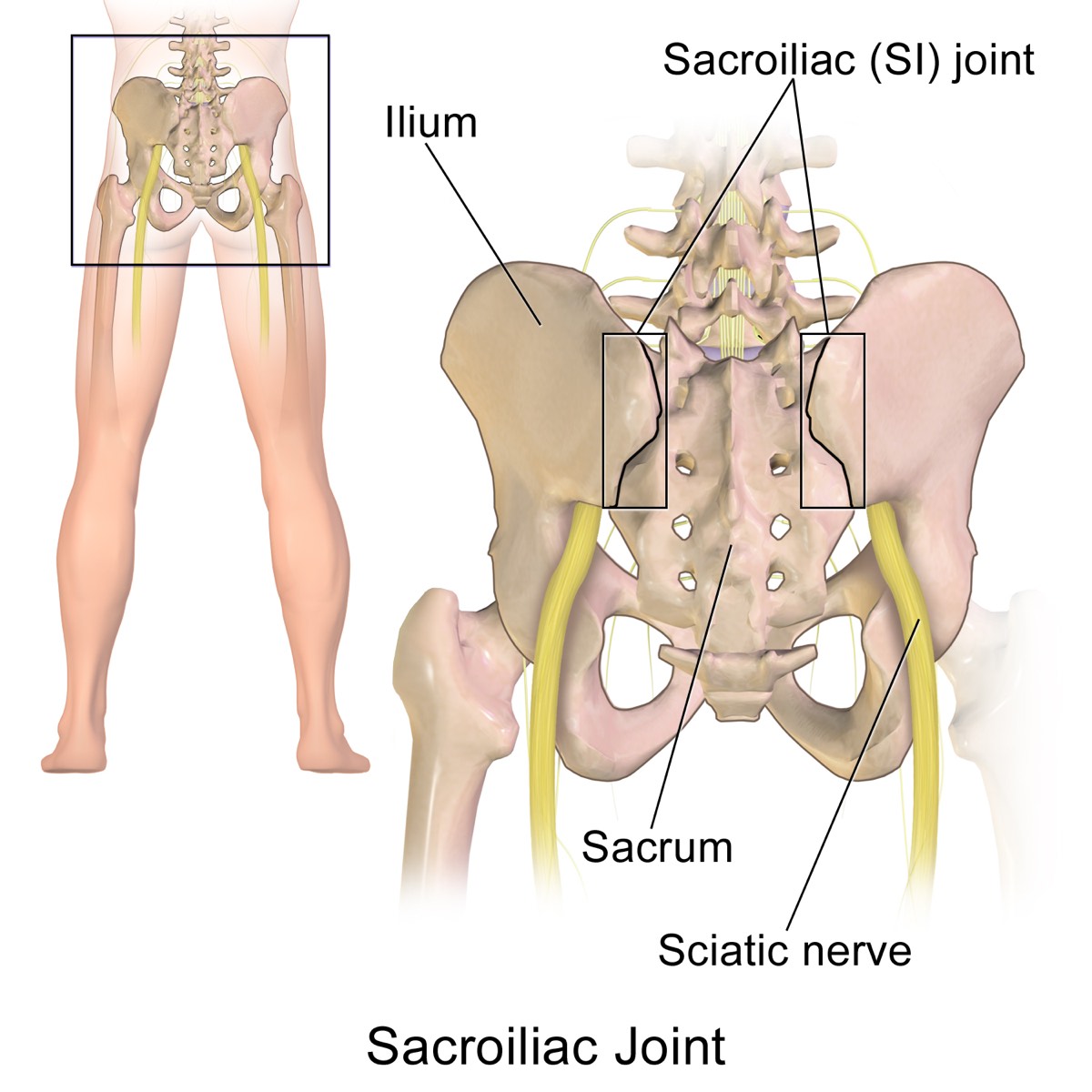

While runners may be less likely to experience chronic low-back pain in general, they are at higher risk of certain causes of low-back pain, such as sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction (16), because of the involvement of running’s alternating one-leg stance. Runners are also at higher risk of spine and pelvis stress fractures, and these should always be considered in a runner with sudden-onset, low-back pain. Female runners with a body-mass index of less than 21 have been found to be at higher risk for spine injuries in general (20). Finally, some runners do experience the most common causes of back pain, which will be discussed in this article as they can keep a person from running or lead to compensatory injuries if not addressed.

This balance of this article will discuss:

- The most common types of back pain,

- Back-pain causes,

- Prevention and treatment strategies,

- Case reports from three runners with back pain, and

- An interview with back-biomechanics expert Dr. Stuart McGill.

Background on Back Pain

Pain from the spine is generally divided into two categories:

- Axial: The pain is in and from the back itself.

- Radicular: The pain may or may not be in the back, but there is a radiating pain that may or may not include weakness in the leg from the pinching of a nerve in the back which travels down the leg. (This type of pain is also often called sciatica even though, in this case, it is not caused by compression of the sciatic nerve itself.)

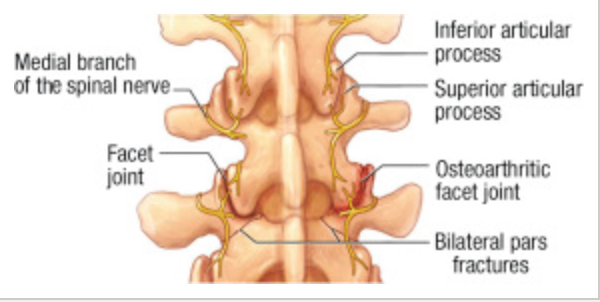

Axial low-back pain in adults under age 55 is most likely to be discogenic, or from the intervertebral disc. Axial low-back pain in adults age 55 and older is typically facetogenic, or due to arthritis of or damage to the back’s facet joints (the joints where the vertebrae come into contact with each other) (4).

A bulging disc (top) and a degenerating disc (below). These findings may or may not cause pain. Image: Hooten, et al, 2015 (10)

Normal facet joints (left) and arthritic facet joints (right). This arthritis may or may not cause pain. Image: Hooten, et al, 2015 (10)

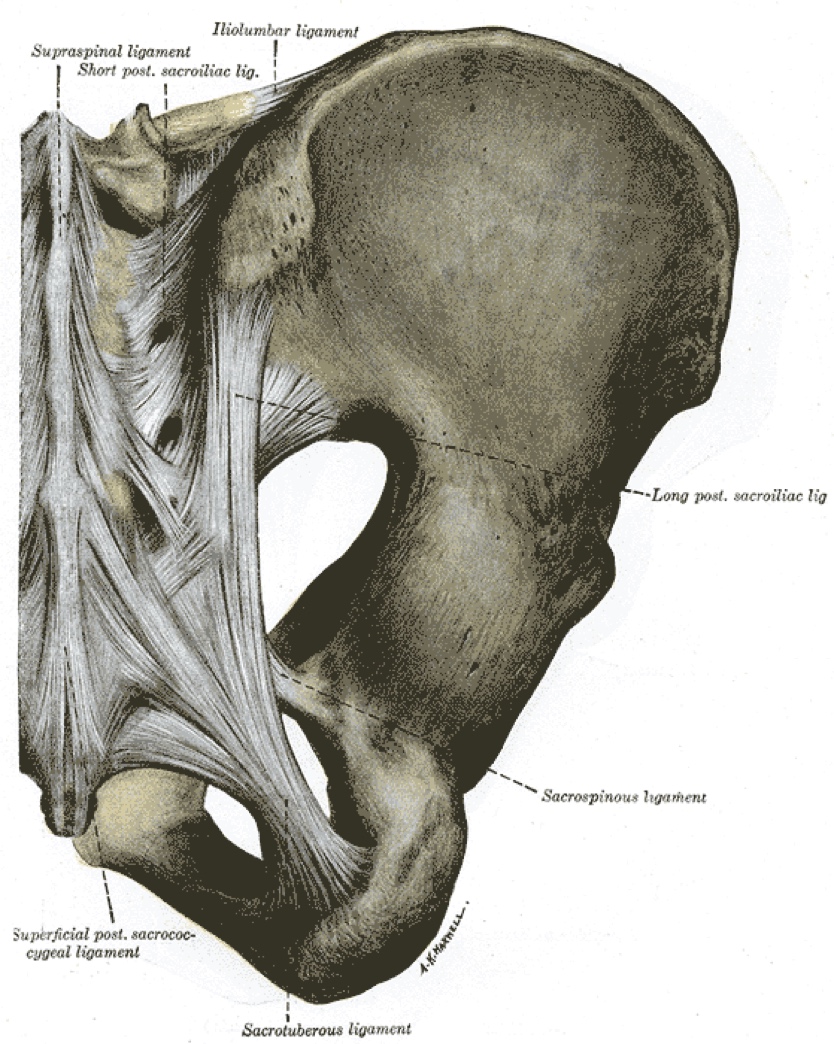

The third most common cause of axial low-back pain is SI-joint dysfunction (4). The SI joint can become arthritic and less mobile with age or its ligaments can become injured or loosen. The latter two are more likely in runners, particularly in females who are or have been pregnant, as the SI-joint ligaments loosen during pregnancy.

The sacroiliac (SI) joint’s location in the pelvis. The joint itself and/or its ligaments can be a source of pain. Though the sciatic nerve is shown, it is rarely affected by an SI-joint issue. Radiating pain down the leg is more typically from a problem in the low back. Image: BruceBlaus

The ligaments of the sacroiliac joint which can become injured or loosened and painful. Image: Henry Vandyke Carter

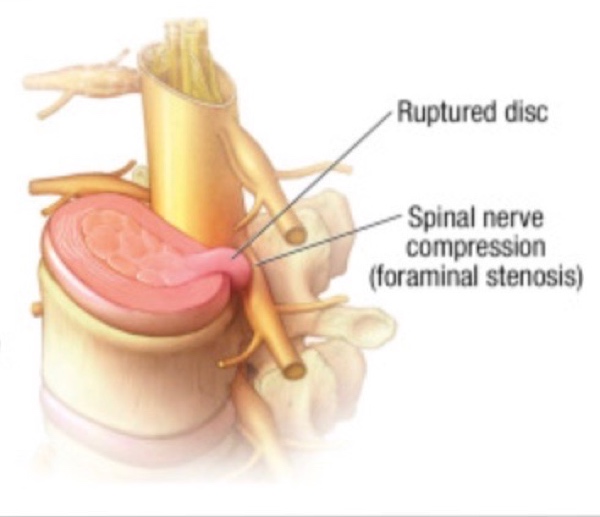

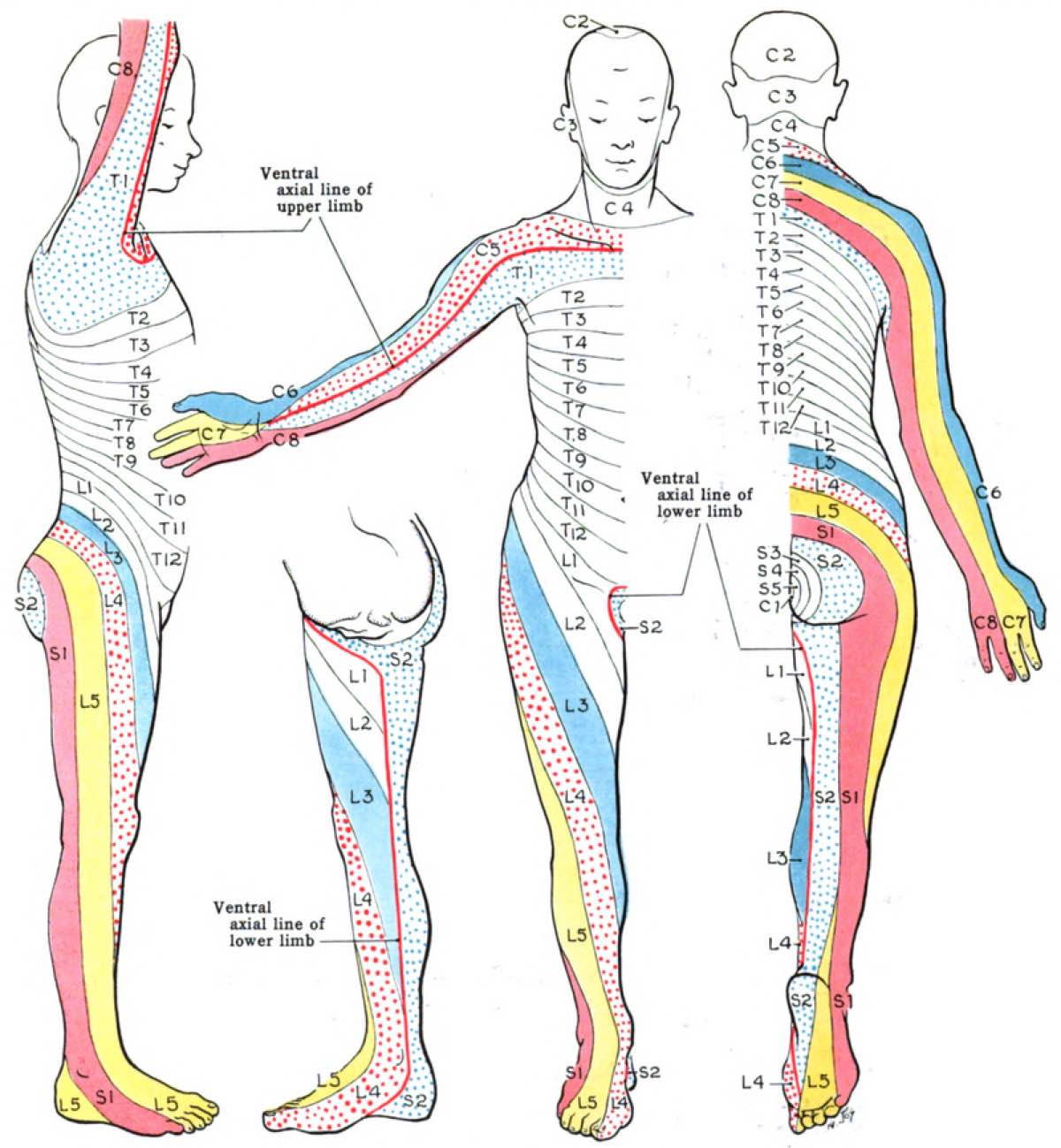

Radicular pain from a nerve root causing burning or shooting pain down the leg can be due to either a protruding or ruptured (also known as herniated) intervertebral disc touching a nerve root or arthritis of the spine, the latter of which causes narrowing around one or more nerve roots which feed a part or parts of the leg(s) (10). This pain in the buttock/lateral hip and legs may also be accompanied by weakness, which occurs in a dermatomal distribution (meaning it occurs by areas of the skin supplied by a single spinal nerve). This gluteal/lateral hip pain traveling down the leg is often incorrectly attributed to piriformis syndrome (the existence of which is debated among the medical community and it is exceedingly rare, if it exists at all) or a muscle pull.

A ruptured (or herniated) disc pressing on a nerve root can cause pain down the leg. Image: Hooten, et al, 2015 (10)

The distribution of pain (and approximate distribution of weakness) due to the pinching of a nerve/nerves coming from the low back (and neck in the case of the arms). Image: John Charles Boileau Grant

About 70% of people with axial low-back pain can expect to have complete resolution of their symptoms within a year (8, 10). And about 90% of people with radicular pain can expect resolution of their symptoms in six months (7, 10). This resolution has been shown to occur with conservative care only.

What Causes Back Pain?

What you do on a day-to-day basis has a large impact on whether or not you will develop back pain. Specifically, a large study showed that low-back pain was found to be attributable to lifestyle 75% of the time in men and 100% of the time in women (6). Sitting for more than half a work day, in combination with whole-body vibration (think planes, trains, automobiles, and perhaps the worst, helicopters) and/or awkward postures, increases the likelihood of having low-back pain and/or sciatica. The combination of these risk factor leads to the greatest increase in low-back pain (13).

While there are myriad risk factors for low-back pain (including psychosocial factors such as depression and pending injury litigation), I would like to keep this section as simple as possible by stating that you should maintain a neutral spine posture as much as you can in all aspects of life and athletics. Here are a few examples of how and when to do so:

- Whenever you are sitting, do so neutrally and avoid slouching.

- When bending to pick something up, keep a neutral spine and bend your knees, not your low back.

- Keeping a neutral spine in weight training is critical. Deadlifts are a good example of an exercise that can be injurious to the spine if not done in the neutral position.

- Avoid any activity that simultaneously torques and loads the spine with weight, especially in the morning when there is increased fluid in the intervertebral discs and they are thus at higher risk of injury.

Beyond that, good-quality sleep, a healthy diet, and a low level of stress hormones can all work together to prevent and heal back injuries.

Sitting with a neutral spine versus slouching. Image: Harvard Health Publishing

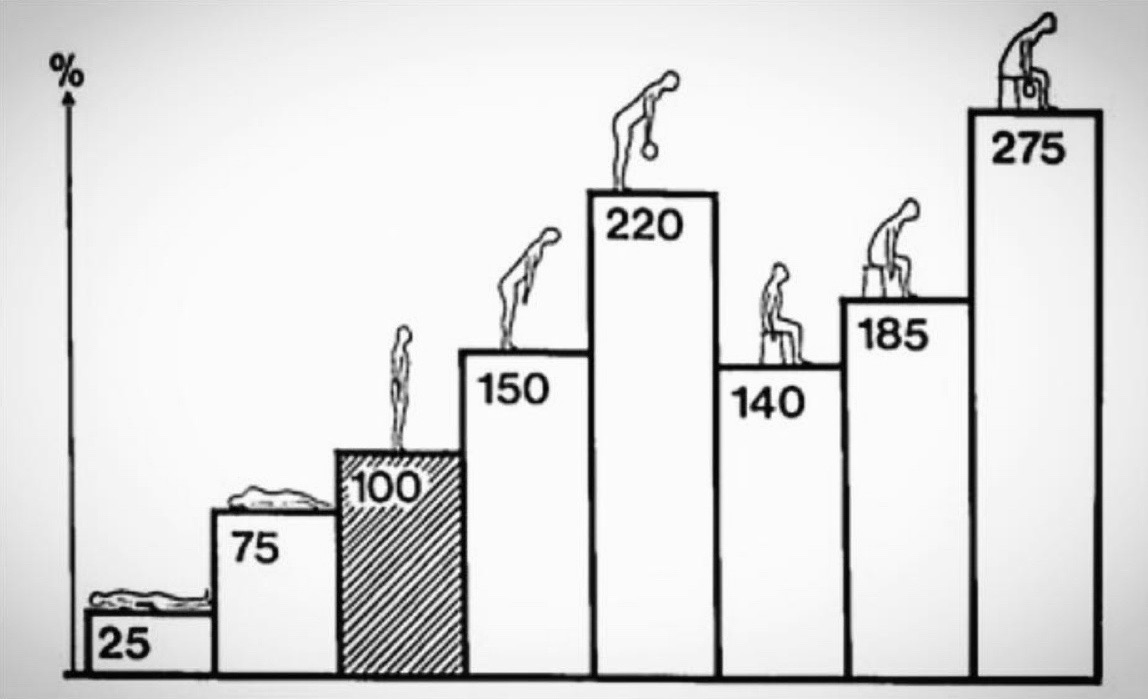

Average disc-pressure measurements in pounds per square inch for different body positions. Even though the pressure is very low in your discs while lying flat and this is non-injurious, some pressure on the discs while standing, walking, and running is good for disc health. Loading the discs in forward flexion (without a neutral spine) may predispose to disc injury. Image: Nachemson, 1981 (14)

Treating Low-Back Pain

Rather than seeing back pain as a disease that needs to be treated, I argue that:

- The exact cause of the pain should be identified, and

- The activity (or lack of) that led to the current issue should be remedied.

Typical causes of back pain are rarely a disease. (However, spinal fractures from cancer or osteoporosis are certainly the result of a disease process that should be treated.) As a physician, I am saddened that opioid medication and surgery are continually offered as treatments for low-back pain, often with significant harm to the patient. Up to 40% of people who have surgery for low-back pain fail to have resolution of their pain (21) and, even if their pain is gone, many surgeries have lifetime-lasting side effects.

However, some runners/patients do not have resolution of their back pain following activity modification, trigger avoidance, physical therapy, targeted exercises, and manual therapy. Before surgery is considered in these patients, these less invasive treatments with good to excellent evidence can be considered:

- Intervertebral-disc pain, causing low-back pain with sitting, may be successfully treated with intradiscal platelet rich plasma (PRP) (22, 17, 15, 3);

- Nerve ablation (12), prolotherapy (concentrated dextrose injection) (9), or PRP for SI-joint ligaments (17);

- Nerve ablation or PRP (17) for facet-related pain; and

- All stress fractures or bone-stress injuries need to be treated with avoidance of the activity which led to the fracture.

Intervertebral discs have poor blood flow and thus are not good at repairing themselves once injured. While a bulge can retreat, tears are often painful and resistant to healing. Due to this, the use of intradiscal PRP is being used increasingly to promote disc healing. A randomized clinical controlled trial (22) has shown PRP injection intradiscally to be superior to sham injection for discogenic low-back pain.

PRP is obtained from a person’s own blood via a blood draw and centrifuged to separate a concentrated solution of the person’s platelets. The patient’s own platelet solution is injected into the disc and the platelets attract growth factors, stem cells, and in general act as the body’s cells that signal a need for healing. Please see my previous article on regenerative medicine for more details on this form of treatment.

For those interested, PRP is very low risk and can be done without sedation (15). In our practice, 318 patients and 748 discs have been treated with intradiscal PRP. A review of intradiscal PRP from 2018 found intradiscal PRP to be a “safe, effective, and feasible… treatment of discogenic back pain” (15). However, at this time intradiscal PRP is not covered by most insurances and may cost a few thousand dollars.

Case Studies of Low-Back Pain in Trail Runners and Ultrarunners

Case #1: JJ’s Low-Back Pain

JJ had a five-year history of severe low-back pain at its worst with sitting. Prior to this, she would run for hours at a time, but as the back pain worsened she could not run more than 20 minutes before excruciating back pain caused her to stop. She had no radiating symptoms down her legs. There was no particular injury that preceded the pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the back showed a herniated and torn L4-L5 disc. (This is the disc between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae near the bottom of the spine.) Physical therapy, manual manipulation, activity modifications, time, and over-the-counter medications had failed to resolve her pain.

JJ’s spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The L4-L5 disc is darker than the others, is herniating posteriorly, and has a high-intensity zone (a white spot in the herniation) indicating a tear. Image: Bodor, 2019 (3)

JJ was successfully treated in our clinic with a PRP injection into the damaged L4-L5 disc. Six months following the injection she had experienced significant improvement and was running 10-plus miles daily. By one and a half years post-PRP, her back pain had completely resolved and her MRI showed disc healing. Two years after the procedure, she gave me full permission to share her story.

Case #2: Nate Bender’s Low-Back Pain

In 2013, Nate Bender had his first episode of severe back pain. He describes, “I was bending over and pulling on a boat that was stuck on a rock when I felt a sudden, sharp, and tearing pain in my back. It was a pretty classic first acute stage where I couldn’t move much for about five days, then slowly got back into regular life over the next few weeks. The symptoms resolved temporarily with chiropractic and self-care in four to six weeks or so.”

Nate Bender on the Beartooth Plateau of Montana in 2018 when he summited all 27 of Montana’s 12,000-foot-plus peaks in a single push of four-plus days. Image: Forrest Boughner

Fast forward six years of physical therapy, chiropractic, and steroid injections later, Nate continues to run but finds himself in an increasingly worse situation with his back. Thankfully, it seems he now has the correct diagnosis. But how did he get there and what sort of treatment will work for him? This interview explores these questions.

iRunFar: What happened with your back after that river trip?

Nate Bender: Throughout the winter of 2017 to 2018 and the spring of 2018, the low-level discomfort started becoming increasingly frequent. I decided to seek out more advanced medical help, starting with physical therapy. This made slow progress and I wanted to understand what was causing the pain once and for all, so I committed to the expense of seeing spine specialists. They ordered a bone scan which pinpointed some inflammation and degradation in my lumbar facet joints, specifically at the L3-L4, L4-L5, and L5-S1 levels. They followed this up with three facet corticosteroid injections at these levels in May, June, and July of 2018, respectively.

iRunFar: This is an interesting scenario since they ordered a bone scan instead of the usual MRI. Certainly the facets could appear inflamed due to taking on load from damaged discs. Also, facet pain is uncommon in younger people and typically occurs with back bending or prolonged standing. Disc pain tends to come on with sitting or bending over and, the worse it is, it can occur with standing and walking as well. Did the injections help? Did you ever get an MRI?

Bender: After that July injection, I was symptom-free from August of 2018 until March of 2019. Then, a day of backcountry skiing sent me into a major relapse where I was incapacitated again for several days, requiring another [steroid] injection. From there I was nearly symptom-free until a month ago, when another big day in the mountains sent me into a relapse. This time I scheduled another injection as soon as possible.

However, this [steroid] injection brought zero relief, and we decided to get an MRI to better understand what was going on. The MRI showed a bulging disc at the L4-L5 level and this disc is pressing on some nerves going to the legs as well as a torn disc at the L5-S1 level.

iRunFar: This is a complicated case, but my feeling is the stress on the facets seen on the bone scan was a red herring and may have been from the disc damage at L4-L5 and L5-S1 and that these disc issues, particularly the tear, was the likely cause of pain all along. Of note, bulging discs are very common and usually not painful, but disc tears can certainly be painful.

At this point, I would want to know your pain triggers and whether or not you are tender on the disc or facets to palpation. If pain comes with sitting and bending over, the disc is the likely pain cause. If the pain comes with twisting and bending back, the facets are the likely cause. If there is pain radiating all the way down the leg(s) to the foot/feet, this is likely from the nerve-root compression (likely at the L4-L5 level where there is stenosis or narrowing around the nerves). Once I arrive at a diagnosis, I would either treat the disc with PRP or the facets with a nerve ablation or PRP to avoid the negative effects of repeat steroid injections or treat the stenosis or radicular pain with a targeted steroid injection or continued physical therapy.

What is the plan now in your treatment?

Bender: The plan is to get an interlaminar epidural injection into the spinal canal at the L4-L5 level, and cut out all of my upcoming projects and races through the rest of the summer and fall so I can double down on physical therapy. This seems to be the most promising option for getting out of this cycle of feeling good followed by a painful relapse.

iRunFar: Epidural injections are most effective for radicular pain (or sciatica) which goes down the legs to the feet. Are you having pain down your legs?

Bender: No radiating pain, thankfully. In terms of pain triggers, I’ve naturally shied away from heavy lifting over the past two years. Some of the triggers have been moving a medium-weight piece of furniture up a flight of stairs, picking up a light laundry basket, rock climbing and scrambling, and trail running.

iRunFar: This all sounds like a pretty classic pain from a damaged disc. I would recommend looking into intradiscal PRP as a more long-term solution than epidural injections. An epidural may provide temporary relief, but would not be expected to treat the actual disc problem. However, intradiscal PRP isn’t generally covered by insurance.

Bender: Okay, I’ll do some research. None of the medical practitioners I’ve talked with have mentioned this procedure. I do have a tear at the L5-S1 disc and I believe this tear was part of the first, acute injury five years ago that likely started this whole process.

iRunFar: I agree that the disc tear was likely the first acute injury, as the mechanism of injury and symptoms fit, though of course it is impossible to say for sure. Thank you so much for sharing your experience.

Case #3: Paul Terranova’s Pinched Nerve

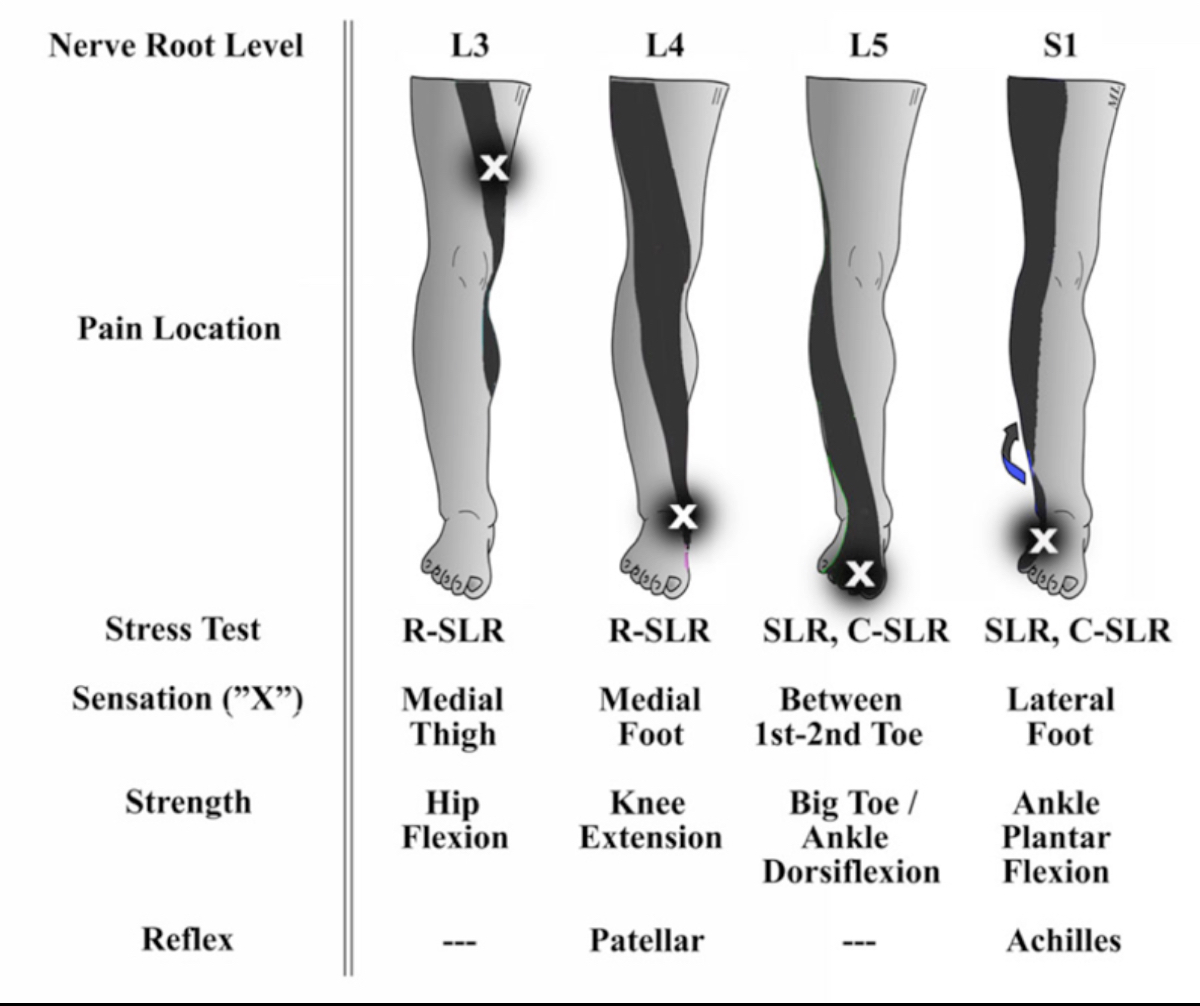

We shared Paul Terranova’s femoral-stress-fracture story in our recent bone-health article. One detail not included in that article, to stay focused on his bone injury, was that he was also found at the same time on MRI to have a pinched L4 nerve root from the low back in the same leg as the fracture. L4 nerve root pinching can cause weakness in knee extension. Paul’s L4 radiculopathy may have caused weakness of the muscles (quadriceps) directly overlying his injury or caused a compensatory running pattern that led to the stress fracture.

Granted this also could have been an incidental finding in Paul’s case, but demonstrates weakness and pain patterns one can have from a problem in the back. Paul was fortunately able to return to full weight bearing and pain-free running without any interventions beyond use of the Alter G (a decreased-gravity treadmill) and running-gait modification following a gait analysis.

The L4 column shows the distribution of pain and weakness that Paul Terranova may have been experiencing. Also, the pain and weakness distributions are shown for L3, L5, and S1 nerve-root compressions coming from the back, which can cause pain, weakness, and a loss of sensation and reflexes. Image: Lin, 2009 (23)

Preventing Low-Back Pain

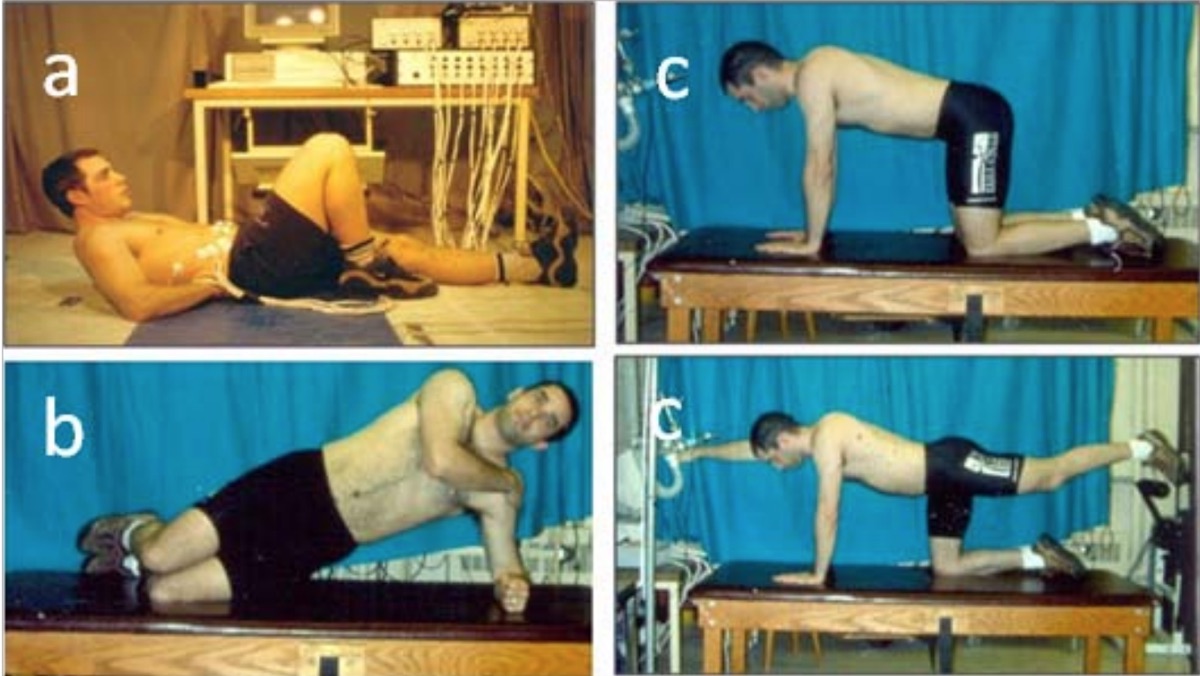

The spine is not able to bear more than 20 pounds of load without the assistance of our core/postural musculature. Core stability and strength is not just a fad but is required to protect the spine. Stuart McGill, PhD (in spine biomechanics) and Professor Emeritus at Waterloo University in Canada has measured the most effective exercises, now called the McGill Big Three, for creating core stability without increasing risk of injury. The three exercises are:

- Curl-ups;

- Side bridges; and

- Bird dogs.

This video demonstrates how to perform the McGill Big Three back exercises.

Interview with Dr. Stuart McGill on Back Biomechanics

For specifics on back-injury prevention in runners, I interviewed Dr. Stuart McGill, author of several books on reducing back pain including Back Mechanic.

iRunFar: Are there specific types of back injuries that runners tend to get, as opposed to weight lifters or gymnasts? If so, what are they and what does running do that predisposes to this injury/pain?

Dr. Stuart McGill: Yes. First, there is a big difference between an Olympic weight lifter and the typical person who lifts weights. If we take the typical person, then generally their pain will be linked to discogenic disorders with several possible pathways, quite often fissures through the annulus[, an intravertebral disc’s outer layer,] caused by repeated and loaded spine flexion due to poor form, inappropriate recovery and exercise selection, and more. Gymnasts usually fall into categories from excessive motion, for example spondylolistheses[, or the slipping of vertebrae from their natural position].

Recreational runners usually do not have specific pain pathways for low-back pain from running itself. Some distance runners tend to become thoracic kyphotic[, where the thoracic spine rounds forward,] as they age, which may be problematic for some. But most recreational runners who come to me either have asymmetric hips leading to chronic spine stress or they have gotten too heavy with loading in the weight room.

I could go on, but really we need to discuss each individual case and in summary I am not concerned about running itself.

iRunFar: I am aware of the three exercises you recommend for maintaining spine health and stability. Beyond these, is there any sort of strength or mobility training you would recommend for runners to avoid back problems?

McGill: Nothing for runners as a group, only for each individual runner. If they present with back pain, we perform a thorough assessment to root out the cause and address it. Then we build the foundation they are lacking for pain-free running. For example, if they have height loss at a single joint and micromovements in shear that are triggering pain, then the big three are usually helpful. But the assessment will reveal the cause and we then have a roadmap to follow. Sometimes there will be an emphasis on core stiffness, other times it may be to mobilize a psoas muscle on one side, or it may be to simply change what they are doing in the weight room or perhaps give them a lumbar support for sitting at work. Again it depends on the individual. I have had many Olympians who run, and each was given a different plan.

iRunFar: There is some evidence that running improves intervertebral-disc health. Have you found or would you expect that runners would be less likely to develop back pain or spine problems than the general population or in other sports?

McGill: Certainly less than other sports. I don’t know of many professional golfers, for example, who do not have some pain to manage. I know lots of runners where back pain is not an issue for training or performance.

iRunFar: For anyone reading this article who has a sitting/desk job or a long commute, are there simple changes you could recommend to improve spine health and avoid back pain?

McGill: Absolutely, read Back Mechanic. The self-assessment will guide them on their most appropriate intervention. They may do well with a lumbar support while sitting, a sit-stand workstation, or more. You know the answer: a thorough assessment will always show the way.

iRunFar: Thank you so much!

[Author’s Note: For more information from Dr. McGill, I highly recommend this podcast.]

In Summary

- Back pain is common.

- Running appears to confer some protection against back pain from intervertebral-disc damage.

- However, runners also experience back pain, including pain from the discs, facet joints, SI joints, and radiating pain down the legs from lumbar-nerve compression.

- The development of low-back pain is highly related to lifestyle factors.

- Most back pain resolves on its own or can be treated with targeted physical therapy, activity, and biomechanical modifications.

- Recurrent or persistent back pain with bending, sitting, or running may be due to a damaged disc.

- Pain radiating down the legs can be from a compressed nerve root in the spine and may also cause weakness in the legs, possibly predisposing to a running-related injury.

- Simple lifestyle adjustments and core-stability exercises can help prevent back pain and damage to the spine.

- There are some exciting, new, minimally invasive treatments for persistent low-back pain that does not resolve with conservative treatments or time.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Are you a runner with low-back pain? Have you had a specific diagnosis and do you have a treatment path?

- Have you had low-back pain in the past? If so, what therapies helped to resolve it?

References

- Belavý DL, Quittner MJ, Ridgers N, Ling Y, Connell D, Rantalainen T. Running exercise strengthens the intervertebral disc. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45975. Published 2017 Apr 19. doi:10.1038/srep45975

- Brisby H, Wei AQ, Molloy T, Chung SA, Murrell GA, Diwan AD. The effect of running exercise on intervertebral disc extracellular matrix production in a rat model. Spine (Philadelphia, PA, 1976) 2010;35(15):1429–1436.

- Bodor, M. Biologic treatment for painful discs: fact or fiction? Oral presentation at University of California-San Francisco Neurosurgery Update. 8/1/2019. Sonoma, CA.

- DePalma, JM & Ketchum, TS., What Is the Source of Chronic Low Back Pain and Does Age Play a Role?, Pain Medicine, Volume 12, Issue 2, February 2011, Pages 224–233.

- Gordon R, Bloxham S. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(2):22. Published 2016 Apr 25. doi:10.3390/healthcare4020022

- Hartvigsen, J, et al.. Genetic and environmental contributions to back pain in old age: a study of 2,108 danish twins aged 70 and older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004 Apr 15; 29(8): 897–902.

- Hakelius, A. Prognosis in sciatica: a clinical follow-up of surgical and non-surgical treatment. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1970; 129: 1–76

- Henschke, N., Maher, C.G., Refshauge, K.M. et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ. 2008; 337: a171

- Hoffman MD, Agnish V. Functional outcome from sacroiliac joint prolotherapy in patients with sacroiliac joint instability. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2018 Apr 1;37:64-8.

- Hooten, W. Michael et al. 2015. Evaluation and Treatment of Low Back Pain Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Volume 90, Issue 12, 1699 – 1718.

- Kenny W.L., Wilmore J.H., Costill D.L. Physiology of Sport and Exercise.5th ed. Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL, USA: 2012.

- Leggett LE, Soril LJ, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for chronic low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(5):e146–e153. doi:10.1155/2014/834369

- Lis AM, Black KM, Korn H, Nordin M. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(2):283–298. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0143-7

- Nachemson AL. Spine (Phila Pa 1976).1981 Jan-Feb;6(1):93-7.

- Mohammed S, Yu J. Platelet-rich plasma injections: an emerging therapy for chronic discogenic low back pain. J Spine Surg. 2018;4(1):115–122. doi:10.21037/jss.2018.03.04

- Prather H, Hunt D. Conservative management of low back pain, part I. Sacroiliac joint pain. Dis Mon. 2004;50(12):670–83.

- Sanapati J, et al. Do Regenerative Medicine Therapies Provide Long-Term Relief in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Pain Physician.2018 Nov;21(6):515-540.

- Smeets R., Wittink H., Hidding A., Knottnerus J.A. Do patients with chronic low back pain have a lower level of aerobic fitness than healthy controls? Are pain, disability, fear of injury, working status, or level of leisure time activity associated with the difference in aerobic fitness level? 2006;31:90–97. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000192641.22003.83.

- Säämänen AM, Puustjärvi K, Ilves K, Lammi M, Kiviranta I, Jurvelin J, Helminen HJ, Tammi M. Effect of running exercise on proteoglycans and collagen content in the intervertebral disc of young dogs. Int J Sports Med. 1993;14(1):48–51.

- Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):95–101. doi:10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95

- Thomson S. Failed back surgery syndrome: definition, epidemiology and demographics. Br J Pain. 2013;7:56–59.

- Tuakli-Wosornu YA, Terry A, Boachie-Adjei K, et al. Lumbar intradiskal platelet-rich plasma (PrP) injections: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled study. 2016;8(1):1–10.

- Lin M. Pitfalls in Low Back Pain High Risk Emergency Medicine 2009 Oral Presentation. San Francisco General Hospital Emergency Services Associate Clinical Professor, UC San Francisco.

- McGill, S. Designing Back Exercise: from Rehabilitation to Enhancing Performance. Accessed from https://www.backfitpro.

com/documents/ RehabtoEnhancing.pdf on 8/15/2019.