The sound of shivering in a bivy sack grabbed my attention. I wasn’t really asleep; the choice to not carry a sleeping pad had been haunting me all night. I sat up to see which of my compatriots was shivering and caught the slightest glow of dawn on the horizon. I laid back down, not having identified who was cold, but now knowing that the long night was about to end.

For several months, my friend Jared Campbell and I had been scheming about a really long run in the newly proclaimed Bears Ears National Monument. The monument proclamation was the result of decades of work, most recently led by a consortium of five native tribes. The northern border of Bears Ears is located not far from Moab, Utah and it extends to the San Juan River near the border of Utah and Arizona. The monument is 1.2 million acres and encompasses varying ecological zones and significant cultural remnants. Our primary goal was to travel on foot through an extensive section of the Bears Ears in the form that we know best: running. By the time we started our trip, we had settled on a route that would be somewhere in the neighborhood of 130 miles and would visit some of the monument’s better-known areas and some of its lesser-known canyons.

This area was given national-monument status on December 26, 2016, as was done so via a proclamation by the U.S. President. Though one person made this ultimate designation, it was the culmination of years of work by countless individuals, dozens of environmental groups, and local and state leaders and politicians. Due to an anti-federal-government sentiment that pervades the West, however, the proclamation was met with resistance and controversy, even though polls show that the majority of people in Utah and the West are in favor of protecting these lands. On a previous visit to Valley of the Gods and Indian Creek, I was given a taste of what was included within the boundaries of the monument, but I had a strong desire to do more than scratch the surface and to try to understand the place.

Just before 11:00 a.m. on an April, 2017 morning, we shouldered overstuffed running packs, bid adieu to our friend who had shuttled us far from anywhere, and began our descent to the canyon bottom. Our group was four: Matt Irving, Steven Gnam, Jared Campbell, and myself. Over the last decade, I have had dozens of adventures with these friends, but it would be the first that all four of us would be together. In our planning, I learned the the most technically challenging portions of our trip would be negotiating down into the deep canyons that transect the area. Despite this, our first descent was on a relatively well-traveled trail on the far western edge of the monument, and we made quick work of getting to the water-filled canyon below.

Travel along the bottom of the canyon was tricky. Thousands of years of erosion had worked its way deep into the surface of the earth and the now-exposed rock was tortuous, narrow, and unforgiving. The deposits of previous flooding, including rocks, trees, and other debris often hung on the vegetation well above the path we traveled. At times it was challenging to pick a route that did not involve wading through knee-to-thigh-deep water, or scrambling over large stones wedged in place by what must have been a seriously impressive flood of water. Steven educated us about the various birds in the canyon, identifying them primarily from their song. It was then that I was introduced to what would become one of my now favorite sounds, the song of the canyon wren.

As we traveled along the canyon bottom, we slowly ascended toward the high country. Water became less frequent and for the first of what would be many instances, I pondered the conundrum of the desert traveler, water. Too much water, particularly if falling from the sky, can be quite problematic. It can make travel slow, or in the case of flash floods, very dangerous. Too little water and the worry becomes dehydration. Fortunately, given the wet winter, the springs that we had identified on the map were flowing well and offered the liquid sustenance that we required. Long after the sun had dipped below the rim of the canyon but still before true darkness settled in, we found a ledge on which to sleep.

It was a long night. In efforts to keep our pack weights at a minimum, we each had made various levels of hard decisions, removing gear deemed unnecessary or too heavy. I had cut out a sleeping pad and chose to carry a hybrid sleeping bag and a down coat. I thought that there would be plenty of sand in the desert to sleep on; I was wrong. Jared and Matt had opted for the suffer-bivy option, both carrying light pads but no sleeping bags. They had lightweight down pants and jackets to sleep in, knowing well that they might be sacrificing warmth for the sake of moving fast. Steven, whose pack was the heaviest, carried a 30-degree-Fahrenheit sleeping bag and a pad. During that first night, we all envied his luxurious sleep kit as the temperatures dropped down to the low twenties on our rocky ledge.

Our second day of travel led us to a juxtaposition of geology and vegetation that I had not experienced, red-rock desert canyons filled with tall ponderosa pines. We followed a path that wound through the narrow forest, and literally walked in the fresh footsteps of a black bear for the better part of three miles. The canyon finally gave way and we popped out on a trailhead high on the mesa. The Bears Ears, the monument’s two namesake buttes, stood off to the left as we gazed south over Cedar Mesa and tried to comprehend what still laid ahead. As we set out, we once again began the task of descending into a canyon below.

This particular descent would be one of the most challenging. Jared had found some obscure beta about a climber’s entrance off the rim and to the canyon bottom, but we had a hard time matching the beta with the terrain. We spent 40 minutes traversing back and forth, up and down, and along the steppes that guarded the canyon, hoping to find a way. There is a risk of traveling in canyon country with three friends who also happen to be expert rock climbers: you may find yourself down climbing a sketchy series of rocky ledges well above the canyon floor. As equally fortunate as risky, we–primarily Jared and Matt–unlocked the route and were able to safely descend to the sandy canyon bottom.

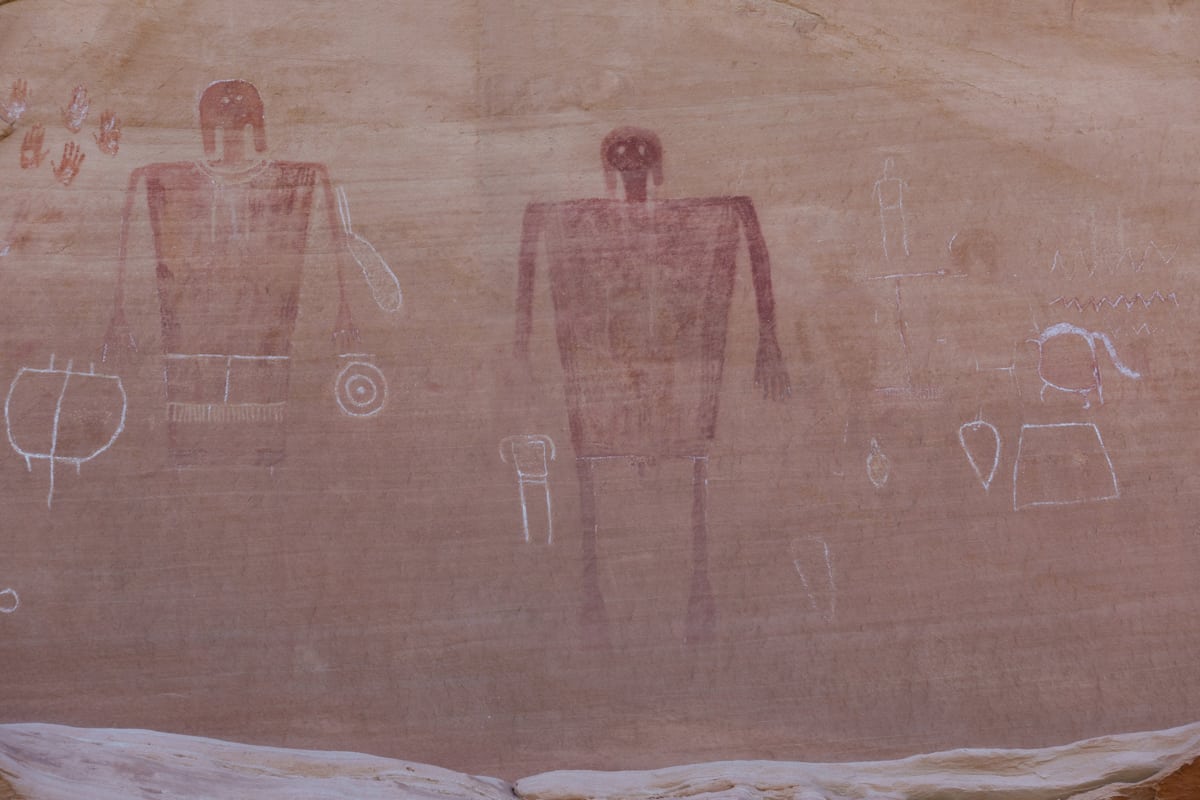

The geology of this canyon beared some resemblance to the previous, but had a different, older feel. The rock much smoother, the walls vertical or overhanging, and a deep soft sand filled the canyon bottom. The travel was slow, the sand absorbing the energy of every step as we tried to run. In many instances, this type of travel would be frustrating, but the constant awe created by the surrounding geology kept the mind distracted from the difficulty of locomotion. Huge rock arches linked the canyon walls, spanning impossible distances. We crossed paths with a couple of day hikers who had entered from a nearby popular trailhead. They would be the only people we would see during our nearly 40-mile day. Late in the day, we were fortunate enough to happen across an incredible set of pictographs and a separate ancient structure. These places, infrequently visited due to their remote location, humbled me, reminded me of the significance of time and the fragility of humanity. Shadows grew long as the day yielded to dusk, and once again as darkness settled in, we arrived at camp.

The route that we had chosen allowed us to stage a vehicle on the side of a road we would have to cross and we arrived at the truck at dark. We made delicious dinners, high-calorie concoctions of grains, salmon, and pretty much everything else we could throw in the pot. With full bellies and warm sleeping bags this time–courtesy of our stashes in the truck–we quickly fell asleep.

We had traveled somewhere around 60 miles in the first two days, and we still had at least that to go as the sun peeked over the horizon on our third day. We once again shouldered packs, supplied now with two-and-a-half days worth of food, and set off to figure our way into the next canyon system. Our first two days were in lesser-known areas of the monument, and the next two would be in the better known. We accessed Grand Gulch via an obscure, infrequently traveled canyon that presented us with another fifth-class entrance, but then showed us some of the most amazing archeology we would encounter. The entire day was filled with amazing panels of petroglyphs and pictographs, and structures that have weathered hundreds to thousands of years. Time and time again, we would come around a corner to be absolutely stunned at the beauty of the combination of cultural history and remarkable geology.

We chose to camp near one of the more popular trails into Grand Gulch and had the unfamiliar experience of being around other people that night. The generosity of an incredible family from Durango, Colorado surprised us in the morning. Two dads and their young daughters were breaking camp near where we were filtering water. They approached and asked if we wanted some oranges, explaining that they hadn’t eaten them and didn’t want to pack them out. It was a simple gesture, but it set a tone of gratitude for the day. Plus, the oranges tasted delicious!

With another long day ahead, and the miles of the previous days heavy in the legs, our small group settled in and quietly ran through geologic time. The canyon had once again shifted from the previous days. The vegetation became more aggressive, laden with thorns and spikes to protect itself, which tore and scratched our sunburned legs. Often the growth covered what sometimes resembled a path, or blocked it out completely. We wove back and forth across the rocky stream bed, up and over sandy benches, constantly moving downstream toward the San Juan River. Around midday, we came across what became my favorite spot of the entire journey: a mass of geology far beyond my comprehension coupled with hundreds of pictographs. I could have spent days there admiring the beauty of the landscape and history, but the trail beckoned and reluctantly we moved on.

At one point we had planned on trying to float out the San Juan River in pack rafts, but the logistics of permits and mandatory gear led us to a different route. We chose to continue traveling in the fashion we know best, and after a chilling swim in the river, we ran on. Our route was a lesser-known link to a separate canyon system, and from reading trip reports from others who had traveled it, it was allegedly terribly difficult. Fortunately it was not as challenging as we thought, probably because we were carrying packs a third the size and weight of the others who had been prior. Travel far above the San Juan River gave us a different and unique perspective for several miles. We could see the river below and the plateau above, and for at time we belonged to neither. The river had once known the plateau, and the plateau the river, but as they distanced themselves they became strangers to each other. This perspective had me pondering the monument’s future, wondering what the middle ground might be, or if it would be possible to even find that space amongst polarized arguments.

After several miles, we again faced the challenge of descending in to the next canyon, the last of our trip. Fortunately, the area is frequented by river folk on day hikes, and the route to the canyon bottom was quite straightforward. Per our routine, we traveled a few more miles until darkness crept in, and then found a suitable sandy ledge on which to sleep. That night, we were serenaded by hundreds of frogs, under a blanket of brilliant stars and flanked by canyon rims. For reasons quite different from our first night out, I had a difficult time sleeping. The beauty of that night was on par with the beauty shown time and time again during the day. The frogs eventually stopped singing and the fatigue of long miles pulled me into a somewhat fitful slumber. I woke several times during the night, not from nightmares per se, but thoughts equally as frightening. What would have been the fate of this place without protection? And, What will become of it if the protection is rescinded or weakened? Those questions made me sick to the stomach then and still do today.

The sun once again greeted us as we shouldered packs, now much lighter with most of our food consumed, and for the final time we set out. We quietly made our way up the canyon, also similar to but still unlike the others. It felt jumbled, raw, and maybe even juvenile. The way the boulders were strewn about and rough around the edges reminded me of a teenager’s unkept room. It turned sharply one way and then back again, much like the actions of a young adult trying to find their place in the world. As often occurs near the end of long adventures, I was quite pensive as the final miles rolled by. I thought of a passage from Kevin Fedarko’s book, The Emerald Mile:

“When you have fully given yourself over to a landscape, without condition or reservation, and when you have come to love that place deeply and with all of your heart, you will do almost anything to celebrate and extend your connection to it. Going slow was a good way of doing that, perhaps the best way of all. But going fast was another way—and if you did it fast enough—it might take you to the same destination.”

We had, over the span of four days, covered the terrain that others have taken weeks or months to travel. The pace, for us, was comfortable and familiar. Some may be critical of our hurried pace through such a remarkable place. Yet, the pace of running over long distances and times does something different: it strips away the layers that we use to cover emotion; it exposes our core. And in doing so, it allows us connect in a way that cannot be done in another fashion. Fierce friendships are forged over hard-fought miles and an unmistakable connection to the place is created. We had set out to get to know a place, and left being part of it, linked to it. As I dropped my pack at the tailgate of the truck, I looked down at my legs and admired the number of bright-red scratches across a nearly equally red sunburn. I had left some of me out there, and it was more than what the plants had held onto. At some point during the run, Jared and I joked that we had only scratched the surface of what lies within Bears Ears National Monument. As it turns out, it was a very deep scratch.

Epilogue

In the weeks and months that have followed our journey in Bears Ears, the monument has been placed directly in the crosshairs of those who have not experienced its beauty. The Department of the Interior has been ordered by the President to review Bears Ears along with all national monuments formed in the last 21 years–26 monuments in total–including Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, also in Utah. They were given 120 days, and only 45 days in the case of Bears Ears.

This is absurd. The level of protection these monuments deserve and have are the result of decades of work by thousands of people. It is a mockery to think that a thorough review of one, let alone all of these monuments, can be done in this time frame, or should even be done at all. We are now awaiting the findings of the review process. Some monuments that were on the list have been “cleared” and no modifications were recommended, yet the fate of others, including Bears Ears, is yet to be announced. The deadline for the review to be submitted to the President is rapidly approaching.

Please take the time to educate yourself on the issue, and then contact Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke and make sure he knows that you think these places, especially Bears Ears, need to stay protected. There is the possibility of a very dangerous precedent being set that could put all of the public lands we as trail runners hold so dear at risk. Contact your local and state leaders, tell your neighbors, share on social media, go stand on the corner and tell every stranger that walks by that their public lands are at risk. Our unified voice will not go unheard.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

We realize that Bears Ears National Monument is a politicized location, and that we may share differing viewpoints on the monument’s establishment and/or the review of national monuments that is currently in progress. All viewpoints are welcome here, but they must be shared respectfully of everyone else and their viewpoints, in accordance with iRunFar’s comment policy. Thank you in advance for doing your part to continue iRunFar’s long tradition of civil discourse.

- Have you visited the newly founded Bears Ears National Monument, or have you previously visited a place in southeast Utah that’s now part of the monument? If so, what did you visit and what was your experience like?

- What does a “deep scratch,” as Luke calls it, look like to you? That is, what sort of experience allows you to get in thick with a place, to learn about it and connect with it? Does it require a certain period of time in a place or a certain degree of knowledge or intimacy? Can you share an example of a time this happened to you?