Summary by Tracy Beth Høeg, MD

Summary by Tracy Beth Høeg, MD

Squaw Valley, California, June 24 and 25, 2014

Conference website

[Editor’s Note: The following are summary reports from the presentations given during the two-day Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports Conference held before the 2014 Western States 100 that the author thought was most relevant to iRunFar readers. Be forewarned, we are talking an almost-encyclopedic treatment of this year’s conference, but it’s all written so that the non-medically trained reader can digest and learn. Enjoy!]

Jump to specific report summaries:

- Cardiac Function in Ultramarathoners

- Neuromuscular Fatigue: Lessons from Extreme Sport

- Effects of Ultra-Endurance Exercise and Carbohydrate Restriction on Membrane Fatty Acids, Inflammation, and Insulin Sensitivity

- Gastrointestinal Distress in Ultramarathoners

- Sodium Supplementation, Drinking Strategies, and Weight Change

- Footstrike and Barefoot/Shod Running Controversies: What Does Science Tell Us?

- Sacrificing Economy to Improve Running Performance: A Reality in the Ultramarathon?

- Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia

- Rhabdomyolosis and Acute Kidney Injury

- Medical Needs at Ultra-Endurance Footraces: Race Director’s Perspective

- Relevant Notes from Day 2

Welcome and Historical Background by Marty Hoffman

Marty Hoffman, MD is the director of research at Western States and the organizer of the conference.

Dr. Hoffman told the group that the idea for this conference came four or five years ago. At that time, there was not enough material to make a conference. Now, Dr. Hoffman said with a smile, there is enough for two days. At this inaugural conference, there were over 100 attendees, which he said was “really amazing.” Most people were clinicians, but some were runners and/or volunteers.

Dr. Hoffman chose the word “ultra-endurance” for the title of the conference because he hopes we can bring in science from other endurance sports in the future. At this point, most of the focus is on running.

Dr. Hoffman mentioned, “There is always a balance between research and the race.” Most of the researchers at Western States are runners interested in helping runners and most runners are interested in the research being done.

Over the last 10 years, there has been an exponential increase in ultra research, and about half of the studies in ultrarunning worldwide came from Western States.

The total number of published, peer-reviewed studies about ultramarathons. The purple bars are Western States-related research. Photo: iRunFar/Tracy Høeg

Craig Thornley, the Western States Race Director, said to me about the conference:

“All the credit for the conference should go to Dr. Marty Hoffman. He is the driving force behind the research at Western States and the medical conference. The race and the sport are fortunate to have him. It was his vision to put on this conference and I have fully supported it.

“The mission of the Western States Endurance Run Foundation is basically a three-legged stool: conducting a world-class 100-mile endurance run, stewarding the Western States Trail, and conducting research directly applicable to ultramarathon running.

“We try to be leaders in all three areas. There is a need to standardize medical care or at least share the knowledge we have gained over the years at Western States and other ultras around the world. With the proliferation of races, especially 100 milers, new race directors and medical directors come to us asking for advice all the time. This conference is a good first step in getting many of the leaders in the sport with respect to medical care together in the same room.”

This report will focus on the more theoretical and research-focused talks of Day 1. Day 2 was more directed to clinicians and health-care workers at races. I will mention some of the highlights from Day 2 at the end.

Cardiac Function in Ultramarathoners

David Oxborough, PhD

Dr. Oxborough received his PhD from the University of Leeds. He travels to California each summer to do imaging tests of Western States runners’ hearts pre- and post-race to learn about the effects of a 100-mile race. He is a nice, down-to-earth guy who allowed me to watch him do a couple of echocardiograms on runners last year while I was researching vision loss. Dr. Hoffman mentioned that, although Dr. Oxoborough is still quite young, he has published over 60 scientific papers.

Dr. Oxoborough gave a talk that was comfortingly similar to the talk given by Dr. Baggish at the American College of Sports Medicine Annual Meeting (which was reported about on iRunFar).

When a person runs an ultra, there are two major types of reactions by the heart: first, an acute (or immediate) reaction to the stress. It appears the longer the race and the fewer ultras you have run up to it, the more your heart reacts to running the ultra. Within 48 hours, the heart appears to return to normal.

Over the long term, endurance exercise causes remodeling in the heart, but the function remains normal. Through Dr. Oxoborough’s and other scientists’ work, we are now understanding that it is the right side of the heart that changes the most in endurance athletes.

Heart chambers.

He said that if doctors and clinicians don’t know that the right atrium grows in ultrarunners, they will probably interpret it as “abnormal.” But, he emphasized, in ultrarunners, this finding is normal. He bases this on his data from Western States.

Dr. Oxoborough is continuing to collect more data about what hearts normally look like on echocardiograms (an ultrasound of the heart) and electrocardiograms (a recording of the electrical activity of the heart) in ultrarunners, so physicians and other clinicians know what to expect and don’t get worried when they see the heart of an endurance athlete.

He emphasized again and again that the function of an endurance athlete’s heart is normal. The one caveat is the apparent increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in endurance athletes. (This has been shown best in a study of over 50,000 cross-country skiers in Sweden.) Also, a change in the heart muscle can look like cardiomyopathy. But he emphasized that even extreme amounts of exercise are correlated with decreased risk of mortality and that the studies that have come out recently in the press about the risks of heart problems from long-distance running have been flawed and/or not peer reviewed. Essentially, our hearts adapt to our activity level and a high level of activity seems to be healthy, as do, generally, the accompanying changes in the heart.

Neuromuscular Fatigue: Lessons from Extreme Sport

Guillaume Millet, PhD

Dr. Millet, originally from France, currently works at the University of Calgary where he is a professor of human kinetics. He has many years of research experience in ultra-endurance exercise, including doing his PhD with Dr. Hoffman and publishing over 100 peer-reviewed articles and four books. It should not go unmentioned that he has placed in the top six three times at the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) and is a consultant for Salomon.

Dr. Guillaume Millet. Photo courtesy of Echo Sciences Grenoble.

Dr. Millet poses an interesting question: why do ultrarunners get tired (or “fatigued”)? Is it the muscles tiring that prevent us from continuing at the same speed? Or is it our brain telling us we are tired?

It is indeed a complex question to sort out, but Dr. Millet has dedicated years of research to understanding this. He has had three major studies on ultramarathoners, one on runners who had run 24 hours on a treadmill, two following UTMB, and one following the 330k Tor des Géants (TDG).

What he has found is that our fatigue plateaus the longer we run. After we have been running for 36-plus hours, it actually decreases though that may be because a lot of these runners (at TDG) actually slept.

After running a race like UTMB, runners have a 35% reduction in maximal force capacity in the muscles of their legs following the race and it is still 2% reduced two weeks later.

It appears that up to 10% of this reduction comes from the muscles themselves fatiguing. Some of this reduction also (probably) comes from signals in the muscle fibers to the central nervous system that there is damage. This can come in the form of acidosis and inflammation. He believes inflammation plays a larger role in ultras than in shorter events.

Some of our fatigue comes from neurotransmitters in our brain. Dr. Millet showed a study which showed that increased seratonin (from tryptophan being released due to our reliance on free fatty acids over glycogen) causes us to feel fatigued.

And it is this subjective fatigue that causes a decrease in voluntary-contraction ability. This seems to be where most of our fatigue comes from.

Dr. Millet did not put a precise percentage on each type of fatigue, beyond the muscles themselves (at around 10%), but he says that there is probably too much focus on the muscular aspects of fatigue rather than the mental.

He also noted differences between men and women. They report the same amount of fatigue after UTMB, but women actually show less signs of fatigue on physical tests post-race. He says this may help explain the theory that the longer the race, the better women do. But he says even that is a theory and may not be true.

There was a question from the audience about how Dr. Millet has changed his own training based on his research and he said he “has started working with a mental coach.”

Effects of Ultra-Endurance Exercise and Carbohydrate Restriction on Membrane Fatty Acids, Inflammation, and Insulin Sensitivity

Stephen Phinney, MD, PhD

Dr. Phinney is Professor Emeritus at University of California, Davis and an expert on the use of low-carbohydrate diets by endurance athletes. He works with Dr. Jeff Volek in studying endurance athletes’ performance on these diets. Dr. Phinney has spent 35 years studying diet and exercise. He received his MD, PhD, and post-doc at Stanford, MIT, and Harvard.

Dr. Jeff Volek (left) and Dr. Stephen Phinney. Photo courtesy of Volek and Phinney.

Before I start this article, I have to thank Zach Bitter (the American 100-mile record holder) and Casper Wakefield of Denmark (the 2013 record breaker of the Yukon Artic Ultra) for introducing me to the concept of increased fat metabolism after they both had such success with altering their diet to achieve this.

Dr. Phinney apparently knew this diet could work a long time ago. But, speaking of Denmark, in 1939 Christensen and Hansen came out with the first study that showed the opposite, that endurance performance tended to be about twice as good on a high-carb diet. And Bergström of Sweden showed in 1967 that athletes who swtiched to a low-carb, high-protein diet performed poorly.

But Dr. Phinney was interested in a book he found on his father’s bookshelf about the Inuits who survived on essentially a no-carb diet. Not only did they survive, but they were nomads and their lifestyle was described in a collection of diary stories entitled The Long Arctic Search by Dr. Schwatka in 1878. Dr. Schwatka lived and traveled with the Inuits for an extended period of time and noted it took him two to three weeks to adapt to their diet.

Dr. Phinney decided to study what he interpreted to be close to the Inuit diet in highly trained cylists in 1983. The diet was composed of 80% fat, 15% protein, and <2% carbs.

At first, Dr. Phinney was surprised that he could suddenly sprint faster than these elite cyclists. But after a period of four weeks adaptation, he saw that the cyclists’ performance returned to where it started, but importantly, they had a significant drop in their respiratory quotient and they were burning over 90% of their calories from fat at 65% VO2 max. This meant that he could see on their very long rides that their glycogen use was reduced by 3.5 times and their glycogen reserves were not depleted.

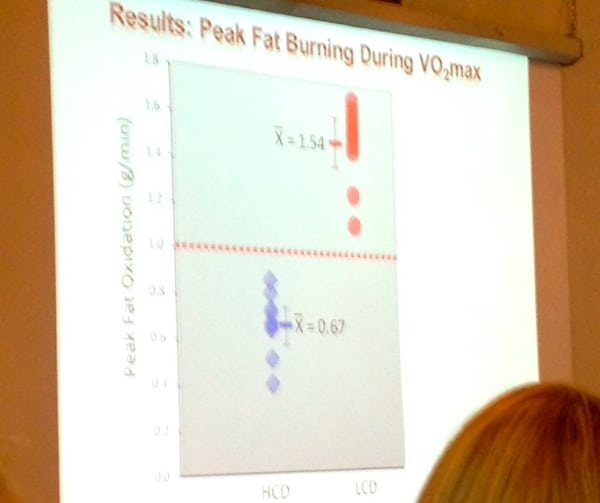

There have been a host of ultrarunners of late who have claimed they have had success with a low-carb, high-fat diet. If you are like me, you have been anxiously awaiting the results of Dr. Volek and Dr. Phinney’s FASTER case-matched control trial study in elite male ultrarunners on low-carb, high-fat versus high-carb, low-fat diets. Dr. Phinney pointed out that the process for publishing data is long and, thus, this may be your one and only opportunity to hear/read about the results for a while.

FASTER stands for “Fat Adapted Substrate oxidation in Trail Elite Runners.” Runners were matched with controls on the basis of competitive record, running times, and age. It is important to note that they were told to continue their “habitual diet” and placed into one of the two categories based on what they ate before the start of the study.

Here is how the study subjects compared on after their first set of tests (there were 10 runners in each group):

HCD: High-carb diet. LCD: Low-carb diet. Photo: iRunFar/Tracy Høeg

The “Low-Carb Diet” (LCD) runners had a lower body-fat percentage and a slightly higher VO2 max on average than the “High-Carb Diet” (HCD).

HCD and LCD composition. Photo: iRunFar/Tracy Høeg

Dr. Phinney made continual note of the low-protein intake in both of the diets. He said neither of these diets is akin to high-meat-content Paleo diets and this is especially important for the low-carb dieters because if you eat low carb but not enough fat, you will not make enough ketones and you may go into a starvation state and experience decreases in your performance.

Results from a three-hour treadmill run in all participants. Red dots are those on the LCD and they were significantly better at oxidizing fat and there was no overlap with the HCD (blue dots). Photo: iRunFar/Tracy Høeg

Fuel usage in the HCD versus the LCD groups during three hours on a treadmill at 65% of VO2 max.

The LCD group has less than 10% reliance on carbohydrates. Dr. Phinney says this is important because they are better at using their fat as fuel–and this was what they expected to see.

He says athletes on a high-carb diet who “bonk” during a race are akin to a gasoline truck filled with a ton of gasoline in the back, but an empty fuel tank. After adaptation to a low-carb, high-fat diet, you are able to access all of your fat reserves and there is at least 20 times more energy stored in our fat than in our glycogen.

What does this mean in terms of performance? In the LCD athletes, if indeed 85% of the fuel comes from fat while these athletes are racing at 900 kilocalories/hour, then they will only need an additional 150 kcal/hour, which can either come from oral intake or glycogen stores. This is a very low reliance on additional energy and should decrease nausea and vomiting and the sensation of low energy.

[Author’s Note: LCD athletes do not necessarily burn 900 kcal/hour. That number was used as a random example and the number is in actuality dependent upon their weight, sex, speed, and the conditions of the course. These things being equal, the LCD and HCD runners are expected to burn the same amount of calories, but the LCD runners are able to meet a much higher percentage of their caloric needs with their own fat stores.]

Beyond this, there is evidence that:

- There is less insulin resistance in low-carb runners.

- A low-carb diet appears to be protective against oxidative stress because the “nutritional ketogenic diet” which these runners are on increases, among other things, arachadonic acid, that protects our cells’ membranes from oxidative damage. There is a ton of oxidative stress involved in running 100 miles because of the enormous amount of oxygen that is required to go through the body. (Dr. Phinney says there may be no better place to study oxidative stress in humans than Western States).

- Increased levels of arachadonic acid may also help protect the stomach from damage.

At the end of the talk, there was a question about women runners who develop eating disorders on this diet and have decreased performance. Dr. Phinney stressed again that if you are going to decrease your carb intake, you need to increase your fat intake otherwise the diet is unhealthy and won’t meet nutritional needs. He also said that he doesn’t place a lot of importance on the particular types of fat a runner gets.

Gastrointestinal Distress in Ultramarathoners

Kristin J. Stuempfle, PhD, FACSM, ATC

Dr. Stuempfle is one of those modest, super-friendly people who seems too down to earth to be an accomplished scientist. She has many years experience researching gastrointestinal distress (GI) in ultrarunners and is a professor at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania.

Dr. Kristin Stuempfle. Photo courtesy of Stuempfle.

GI problems are a big deal in 100-mile races. They are the number-one reason for dropping out and the number-two problem affecting performance (after blisters!).

Depending on the distance of the ultra and temperatures, GI issues affect between one third and two thirds of runners. But why?

- Physiological: Blood flow is diverted away from the GI tract while we are running and decreases by up to 80%. This causes reflux, bloating, stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting.

- Mechanical: Runners bounce around a lot and have a lot more GI issues than cyclists and swimmers.

- Nutritional: Either over- or under-hydration can cause nausea and it can be hard to find the right balance.

What has Dr. Stuempfle’s research shown?

From a study with 272 participants at Western States last year, nausea was the number-one concerning cause of GI symptoms, occurring in 60% of the participants. The severity was on average “mild.”

36% of the runners who dropped out of the race gave “GI symptoms” as their reason and 90% of them had nausea and/or vomiting. If there was nausea early on in the race, there was a higher chance of dropping. Their data suggest that early on, runners with nausea are not able to meet their fluid needs and end up losing more weight.

There was an overall frequency of 96% reporting GI symptoms (including flatulence and belching) at Western States in 2013.

From a small study of 15 runners at the Javelina Jundred, Dr. Stuempfle found a similar pattern of GI symptoms starting at mile 30 was correlated with reduced fluid intake and increased risk of dropping out of the race.

At this study, each runner’s race diet was scrupulously analyzed and runners who ate more fat early on in the race were significantly less likely to develop GI symptoms; this was not true for carbs or protein. She is not sure if this is a case of cause and effect or simply an association.

Sodium Supplementation, Drinking Strategies, and Weight Change

Marty Hoffman, MD

Dr. Hoffman is the director of research at Western States and a professor of Physical Medicine and Rehab at UC Davis. As Craig Thornley pointed out, Dr. Hoffman deserves a lot of the credit for the success of the research and studies coming out of Western States. While Dr. Hoffman is involved in many areas of research, he has become a world-leading expert in hyponatremia (water overload) during exercise. Dr. Hoffman has published research from Western States that has paralleled Dr. Noakes’s (the author of Waterlogged) research from Comrades. These two scientists have started to change the hydration paradigm at long-distance running events from one of “drink as much as you can” to “drink only to thirst,” in response to deaths worldwide cause by water overload among runners.

Some terminology to help digest this section:

Hyponatremia: Below-normal plasma sodium level, as determined by a blood test

Symptomatic hyponatremia: Below-normal plasma sodium level with outwardly visible related signs and/or symptoms

Hypernatremia: Above-normal plasma sodium level, as determined by a blood test

“Several companies have tried to make money selling table salt,” said Dr. Hoffman humorously, showing a slide of all of the brands of salt tabs available to runners on the market.

The average American consumes 3,500 milligrams of salt a day and we should only consume 500mg/day. But do ultrarunners need to take salt tabs during a 100-mile race like Western States?

The short answer is no. Sodium supplementation during an ultra actually has no significant effect on the blood level of sodium at the end of the race (Winger 2013). Runners who only drink to thirst and do not take supplemental sodium also maintain a normal (expected) body weight during a 100-mile run.

Dr. Hoffman showed data from 2011 where some runners actually ended Western States with hyper-hydration (they gained what is considered an unhealthy amount of weight) and had sodium levels that were above the normal range. These runners consumed between 25 and 60 S! Caps each. Dr. Hoffman and the Western States research team no longer pull runners for weight gain (as they have in the past) but now recommend runners should stop taking salt supplementation if they have gained weight.

The way I interpret these data taken together is sodium supplementation is not necessary to maintain normal sodium levels in ultramarathons, but can raise the sodium levels in the blood to an unhealthy level and something Dr. Hoffman did not mention, but concerns me, is that runners with elevated sodium levels and weight gain are at risk of having elevated blood pressure. That is certainly something runners with a history of high blood pressure, heart, or kidney disease should keep in mind.

From Dr. Hoffman’s talk on Day 2: Most runners with symptomatic hyponatremia tend to have gained weight while racing. This was seen in both his study at Western States and Tim Noakes’s study. Runners of 100-mile races are expected to lose between 4 and 5% of their body weight.

Behaviour among runners at Western States has changed between 2011 and 2013. In 2011, 44% of runners drank fluids on a schedule and not after thirst. In 2013, over 50% drank after thirst. Dr. Hoffman was pleased with this and believes this will cut down on the rates of hyponatremia at Western States.

In summary:

Thirsty? Drink.

Craving salt? Eat something salty.

Feeling bloated? Stop drinking.

He concluded by saying that it is actually very simple and people should, above all, listen to their bodies.

Footstrike and Barefoot/Shod Running Controversies: What Does Science Tell Us?

Dr. Kevin Kirby, DPM, MS

The oldest shoe, found in the Fort Rock Cave of central Oregon. Photo by Mitchell Feinberg, courtesy of National Georgraphic.

A term to help with this section:

Creatine phosphokinase (CPK): Also known as creatine kinase (CK), is an enzyme released during muscle breakdown that can be measured by a blood test.

Dr. Kirby ran his first marathon at age 17 and ran his fastest Boston Marathon in 2:31. His bias coming into the talk is he has continually defended shoes over barefoot running and has publicly argued with Chris McDougall (author of Born to Run) about the topic and was asked to write in defense of shoes by Amby Burfoot at Runner’s World.

But he stated at the beginning of his talk that his purpose today was to review what science has found because, as medical professionals who treat runners, that is what we need to hang our hats on.

Ancient images indicate our Greek ancestors ran sprints barefoot in Olympic Games. But shoes were probably around long before that.The oldest known shoe that could be carbon dated was from 8,000 BC and made of woven sagebrush.

Scientists studying fossil foot bones have determined that shoes were being used as early as 40,000 years ago. Fast forward a wee bit and the first known specialized running shoe was made in 1865 for Lord Spencer of England. The first adidas shoes came in 1920 from Adolph Dasler of Germany.

Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, long-distance runners ran in “racing flats.” It wasn’t until the latest ‘70s and early ‘80s that more cushioned running shoes were made available.

Dr. Kirby showed a picture of the book Born to Run–“And then the fun began,” he said with smile.

The 1930s New England Running Shoe and the 1960s New Balance Trackster. Photo courtesy of Runner’s World.

In 2009, people started claiming we should all run like the Tarahumara. People focused on Abebe Bikila’s barefoot win in the 1960 Rome Olympics in 2:15:15, but what they fail to mention is he ran the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo in shoes in the then world-record time of 2:12:11. Not in the last 50 years has any international marathon been won by a barefoot runner.

But…

When you run barefoot, you increase your stride frequency and you decrease impact shock, especially on your heels. Overstriding has long been known as an inefficient running form. Overstriding should be avoided. But, Dr. Kirby notes, you can also learn to avoid overstriding with shoes on.

Vibram Five Fingers were popular minimalist running shoes from 2009 to 2011. He explained that, in California, running-shoe stores could not keep enough on their shelves. He then put up one case report after another of stress fractures in runners who wore Vibram Five Fingers. In 2012, Salzler et al. came out with injury reports in 10 runners who had switched to minimalist footwear: eight metatarsal stress fractures, one with a calcaneal fracture, and one with plantar-fascia rupture. Much more convincing, in my mind, given that essentially all runners develop injuries, was the randomized trial Dr. Kirby presented by Ridge et al from 2013. There were 36 runners randomized to wear “thick soled” shoes or Vibrams and they were given a 10-week transition period to get used to their shoes. More of the Vibram runners had bone-marrow edema (a sign of stress on the bone) and two of them developed fractures compared to none in the “thick sole” group.

But there is a price to running in heavier shoes. For each 100 grams of shoe mass you add, you need to increase your oxygen consumption by about 1% at marathon-racing speed.

adidas Boost. Photo courtesy of Peter Larson.

Interestingly, you don’t save energy by running barefoot, though. This, Dr. Kirby says, is due to your muscles needing to cushion your impact. However, if you run barefoot on a cushioned surface, you require less metabolic power (as demonstrated by this 2014 study). Dr. Kirby made the valid point that one can’t always run on a cushioned surface so, if there is an “ideal,” it is to have lightweight shoes with effective cushioning. He mentioned that the adidas Boost has been shown in the last few months to decrease metabolic rate in some but not all runners.

The adidas Boost has a midsole made of fused polyurethane beads. It has been shown by Dr. Worobets of the University of Calgary to decrease oxygen consumption slightly but significantly, by about 1%, compared with the adidas Eva on both the treadmill and the road (the study).

But all runners are different and will do well in different shoes based on their running background and typical injury patterns. There was a question from the audience about lightweight versus heavyweight body types in runners and Dr. Kirby was quick to respond that lightweight runners seem to need less cushioning and less pronation control than runners who weigh more.

What about landing pattern? Is it worth it for a runner to switch from a rearfoot to a midfoot or forefoot strike? The bottom line was, you simply choose to put stress on different tissues if you land on your rearfoot or midfoot/forefoot.

He listed multiple elite long-distance runners (such as Meb Keflezighi) who are rearfoot strikers and showed video footage of the 2012 10,000-meter USA Championships in Eugene, Oregon where about half the runners were rearfoot and half midfoot strikers.

Runners who land on their rearfoot have a strike impact that midfoot and forefoot landers don’t have (Cavanaugh, 1980). This essentially acts as a brake to forward motion. However, in ultrarunners, Dr. Kasmer and Dr. Hoffman (2014) found that midfoot or forefoot runners who finish Western States have elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) compared with rearfoot strikers. This is likely due to the fact that the calf muscles absorb more shock.

The balance between preventing muscle damage (by rearfoot striking) and having a lower energy cost of running (midfoot striking) will be discussed in the summary of the next talk.

Dr. Kirby does not generally recommend a runner change their landing pattern. However, in the case of repeated injuries, a runner may consider loading different tissues. For example, a runner with repeated Achillles or calf injuries may benefit from a rearfoot pattern whereas a runner with anterior tibialis problems (such as chronic exertional compartment syndrome or [author’s addition] possibly shin splints) may benefit from a midfoot/forefoot pattern.

He does generally recommend that runners focus on shortening their stride length and increasing their step frequency.

A question came from the audience about heel-to-toe drop in shoes. Dr. Kirby seemed to be generally in favor of a low heel-to-toe drop, especially for runners with knee problems. He mentioned he runs a lot in Hoka OneOnes (which have a low 4 millimeter heel-to-toe drop). He also added that it is good practice to switch up the type of shoe you run in during the week so you continually load your muscles and tissues differently, helping to prevent overuse injuries.

Sacrificing Economy to Improve Running Performance: A Reality in the Ultramarathon?

Guillaume Millet, PhD

This talk was both fascinating and complicated, but I think it can be best understood if we boil it down to this question: why is Kilian Jornet such a good runner? Or, in other words, why are some ultra and long-distance runners so good?

Dr. Millet comes from the background of having worked with and run the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc and Tor des Géants , so he generally looks at ultra and trail running as a sport that is done in the mountains.

Some runners finish UTMB with a lot of muscle damage (as measured by CPK). Why is this? Beyond genetics, Dr. Millet believes this can be prevented by eccentric training. He says eccentric training (for example running downhill) should be used a lot more in the preparation for ultramarathon training than it currently is. Also, running technique: the more a runner can fly down a hill with little impact, the more they are protected from muscle damage. He gave the example of Dawa Sherpa.

Dawa Sherpa. Photo courtesy of runner786.com.

Dawa grew up in Nepal and ran in the mountains since the time he learned to walk. He thus practiced both eccentric training and downhill-running technique from very early on. He was the first winner of UTMB. Dr. Millet, who has run a few times behind Dawa, said it was as magical to watch him run downhill as it is to watch Kilian Jornet. Essentialy, Dawa and Kilian are very protected against muscle fatigue because their impact with the ground on downhills is so minimal.

But what about VO2 max? Do runners like Kilian, Dawa and, for example, Paula Radcliffe, simply have a very high VO2 max that allows them to perform better than their running peers?

Kilian Jornet and Paula Radcliffe. Photo: Josh Korn

The answer is no, but we need to do a small amount of math to understand this:

V= F x VO2 max/Cr

V= Ability to maintain a high % VO2 max over a given duration

F= Endurance

Cr= Energy cost of running

If this looks like Greek to you, no worries! The point is, your marathon and ultramarathon performance is not just related to your VO2 max, but also to your endurance (the more the better) and how much energy you require to run (the less the better).

Let’s take the example of Paula Radcliffe again. For the 10 years leading up to her world-record marathon in 2003, she did not increase her VO2 max, but she did decrease her energy cost of running.

Dr. Millet explained what a runner can do to decrease their energy cost of running:

- Improve muscle efficiency: This comes through distance training and an increase in the percentage of Type 1 muscle fibers.

- Flexibility: He mentioned he thought it would be difficult for ultrarunners to get too flexible, so the more the better.

- Running technique: The less impact, the better (so midfoot landing would decrease the energy cost of running compared to rearfoot).

- Anthopometry: Diameters/leg mass (Dr. Millet did not go into detail about what this meant.)

- Percent body fat: Lower is better.

- Neuromuscular capacity (Again he did not go into detail.)

- Lighter shoes (I interpret this to mean less weight carried in general.)

Another thing ultrarunners can work on to improve their performance and to increase the V in the above equation is to increase their endurance (F). Here are the factors he listed that improve endurance:

- Capacity to limit hyperthermia: If you train with speedwork, you won’t tend to get as hot as easily when you run.

- Capacity to feed without GI symptoms

- Stride frequency: If you start out an ultra with a short stride length, you will improve your chance of being able to finish or perform well until the end.

- Rearfoot strike: It will protect you from muscle damage in the long run.

- Run with poles in the mountains to protect leg-muscle fatigue (He mentioned this is very important for beginning mountain runners, but has less impact for habitual mountain runners like Kilian; the extra weight of the poles mean that elite mountain runners get little benefit from them.)

- Protective footwear: Non-minimalist shoes can protect against muscle and tissue injury, especially in newer ultramarathon or mountain runners.

- Psychological factors/motivation

As you can see, there are many ways ultrarunners can improve their performance without improving their VO2 max. In general, the more experience you have in ultra or mountain running, the less you need to focus on the endurance factors and the more you can concentrate on decreasing the energy cost of running. Each individual athlete needs to decide which factors they will benefit most from working on or incorporating.

Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia

Tamara Hew-Butler, DPM, PhD

If you ever need a speaker about the subject of exercise-induced hyponatremia, Dr. Hew-Butler may just be the best one out there. She has an absolutely fantastic energy and I think I speak for the entire audience when I say we were captivated by her presentation of the “spectrum” of factors that can cause fatally low sodium levels in ultrarunners.

Dr. Hew-Butler is an assistant professor of Exercise Science at Oakland University in Michigan and has a background as a podiatrist with a PhD. She worked with Dr. Timothy Noakes in South Africa during her PhD.

Hyponatremia is a decreased level of sodium in the blood. Normally, this level is very tightly regulated but, when we exercise, we tend to retain fluid and sodium goes down. Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia, according to Dr. Hew-Butler include a history of over-drinking, drinking when not thirsty, bloating, vomiting, increased blood pressure, and possibly increased body weight. When drinking continues in the face of these, runners can develop seizures, pulmonary edema, go into a coma, and die from brain-stem swelling. When the level of sodium in our blood is too low, our cells swell. Most importantly, when brain swells cell, we lose neuromuscular control, become confused (and as Timothy Noakes mentioned in Waterlogged, get a headache), potentially develop seizures, and brain-stem herniation, as mentioned above.

Dr. Hew-Butler became interested in the topic of hyponatremia after working in the health care tent of the Houston Marathon in 2000 and witnessed four runners go into critical condition after mistakenly receiving IV fluids at the finish line when they actually had hyponatremia and not dehydration.

She did a study on these runners and learned that they drank up to 100 cups of water over the course of the marathon. At that time, people were so frightened by dehydration that the organizers of the Houston Marathon decided to have aid stations with water/fluid every half mile (of course not knowing at the time, this could be fatal for runners). Her collection of data from three years at the Houston Marathon can be read here.

In one study she did with Dr. Noakes, they learned that for up to 18 hours of exercise in long-distance triathlon, people with hyponatremia tended to gain weight, but some actually lost weight over the course of the race as well. In the second study, they gave salt tabs to half of their study participants in an Ironman triathlon and placebo pills to half and there was the same incidence of hyponatremia in both groups.

Then Dr. Hew-Butler came to Northern California to do research at Western States because 100-mile ultrarunners insisted that they were different and that they needed salt supplementation. It was already known that there was a high incidence of hyponatremia in Northern California ultramarathons. For instance, 51% of runners at the Rio del Lago 100 Mile had hyponatremia on blood testing.

So Dr. Hew Butler designed a study at Western States where she looked at urine concentrations of sodium pre-race, post-race, and during the race. Yes, she had race participants pee in a baggie and leave the baggie on the trail for her poor research colleague to collect. (Apparently one of the baggies broke and leaked on him.) Be that as it may, what did they learn?

First of all, ultrarunners lose very little sodium in their urine, so most of our sodium loss comes from sweat. But when we sweat, we lose about 5% more water than sodium per gram of sweat (that is in any exercise above 40% of VO2 max). What they found at Western States was different than what Dr. Noakes had found in South Africa and that was that those runners who lost the most weight were more likely to develop hyponatremia. This was not consistent with overhydration alone. The study, published in 2013, can be read here.

The Western States study suggested that hyponatremia, at least in Western States, is multifactorial. Dr. Hew-Butler says these factors come into play:

- Drinking despite not being thirsty

- Salt lost through sweat

- Heat

- Increased amount of stress on the body resulting in the production of antidiuretic hormone (also known as vasopressin or arginine vasopressin)

What is antidiuretic hormone (ADH)? It is a hormone secreted by the pituitary gland in response to dehydration. It makes the kidneys hold onto water. ‘Antidiuretic’ means ‘against urination.’ Antidiuretic hormone is also stimulated by hard or long (greater than 60 minutes in habitual marathon runners) exercise. It is also released in response to nausea, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, stress, and heat.

All of the above listed factors that stimulate ADH secretion will increase a runner’s risk of hyponatremia. A runner in a hot, long race who is vomiting and drinking fluid to make up for potential losses is at high risk for developing hyponatremia if exercise and drinking beyond thirst continues.

What is the treatment of hyponatremia?

If mild hyponatremia is suspected, salty broth is effective. If the runner is confused, showing signs of neurological impairment (loss of coordination) or seizures, they should receive IV hypertonic (3%) normal saline. This salty water given directly into the blood supply will almost immediately reduce brain swelling (for the physicians out there, there have been no known cases of central pontine myelinosis following the administration of hypertonic saline in the setting of exercise-induced hyponatremia because it develops over a relatively acute period of time). Typically after receiving this salty IV fluid, runners will no longer be confused and will stop seizing. They should be sent to a hospital and ideally treated by a physician familiar with exercise-induced hyponatremia (and these physicians are rare!).

How can it be prevented?

Drink to thirst and eat salt to taste.

Two interesting side notes from the talk:

- Runners with hyponatremia tend to have loss of bone-mineral density on DEXA scans compared with the start of the race. Dr. Hew-Butler explained this is because they are recruiting salt from inside of their bones and moving it into their blood.

- Hyponatremia, even in runners who are asymptomatic, is also associated with an increase in creatine phosphokinase (released from damaged muscles) and possibly renal failure. The cause or nature of the relationship between these two is not understood, but kidney function should be checked on all runners identified with hyponatremia.

Rhabdomyolosis and Acute Kidney Injury

Robert H. Weiss, MD

Dr. Weiss is the Chief of the Nephrology (kidney) Department at the Veterans Affairs (VA) in Sacramento, California. He will also be the new medical director of Western States this year.

Dr. Weiss gave a very informative, humorous talk about what rhabdomyolosis is and how it relates to kidney failure. It was a very technical, interesting talk, but a few points stuck out as being of interest to iRunFar readers.

Rhabdomyolosis was seen often in crush injuries in World War II. It is what happens when there is rapid muscle breakdown and the damaged muscle cells release multiple substances that can clog the kidneys. In terms of ultramarathoning, dehydration and inadequate training seem to be risk factors. Taking ibuprofen will decrease blood flow to the kidneys, also making kidney damage more likely.

Rhabdomyolosis classically causes “cola”-colored urine, but in the setting of an ultra, it may be normal to have dark urine, so in the absence of unusual muscle pain, dark urine color should not be cause for concern.

[Author’s Note: I was initially introduced to rhabdomyolosis in ultrarunning when Erik Skaggs was hospitalized with it after running a course record at Where’s Waldo 100k in 2009. At that time, I thought the condition was exceedingly rare in ultrarunners.]

Dr. Weiss showed a study of Dr. Brusso and Dr. Hoffman from 2010 where five runners were admitted to the hospital with hyponatremia and four out of five of them went on to develop acute renal failure. One may have had long-term damage to his kidneys.

A quote from the audience about this particular runner with permanent kidney damage was that he was “woefullly undertrained” and had experienced “extreme” muscle pain from mile 50 on, but kept going. Of note, all the runners from the study who developed kidney failure had not been able to train as normal up to Western States due to an injury.

The bottom line of this talk for ultrarunners was to come into your race with adequate training, avoid dehydration, and avoid NSAIDS (such as ibuprofen and naproxen). The main warning sign is extreme-muscle pain accompanied by cola-colored urine. Runners will typically not be given IV fluids until they get to the hospital since hyponatremia and acute renal failure seem to occur together often and hyponatremia is potentially fatal, so any treatment of suspected rhabdomyolisis is delayed until both sodium and creatinine (an indicator of kidney function measured by a blood test) levels can be measured.

Medical Needs at Ultra-Endurance Footraces: Race Director’s Perspective

Craig Thornley, MS

Craig Thorney is an ultrarunner, the director of Western States, and the founder of the Where’s Waldo 100k.

He gave a historical perspective about the medical care at Western States and has a goal of making medical personnel allies (and not enemies) of the runners.

Western States was initially a route taken by horses and the initial medical care of runners in the 1970s was based on the veterinary care of the horses. He showed a picture of Gordy Ainsleigh being examined next to a horse at one of the checkpoints. Probably because of this history, runners were initially treated like horses at the medical checkpoints and physicians made the decision about whether or not it was safe for the runner to continue and the runners had no say.

Runners used to put rocks in their pockets to weigh enough to be allowed to continue. He was actually instructed to do this when he raced so he wasn’t pulled for weight loss. Craig Thornley doesn’t want these things to be going on. He wants the medical team to be an ally to the runners. He hopes that only runners in medical danger will be pulled or stopped and that otherwise the decision to continue will be in the hands of the runners.

He gave examples of multiple runners blogging about being stopped or given an IV against their will, including Pam Smith in 2012. He asked, “Should a physician be told she has to be held?” He also gave the example of Gary Bennington who in 2013 pulled himself (not pulled by the medical team), despite possibly having signs and symptoms that were concerning. He developed seizures from hyponatremia and luckily was treated appropriately in the medical tent at the finish line with a small but rapid dose of very salty fluid (3% saline) through an IV and he stopped seizing.

[Author’s Note: I was working in the medical tent at the finish line when this happened last year. Mr. Bennington was seated right in front of me at the conference, as Craig Thornley pointed out to us, coming all the way from Canada, I imagine, interested in this conference after his experience last year. Interestingly, I am able to write his name since 1. He consented to being identified, and 2. HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) laws do not apply to medical care given at races.]

Craig Thornley pointed out, quoting Dr. Marty Hoffman: “If there is a medical catastrophe at the race, it could negatively impact the entire sport.”

Ideally, you only want to pull the runners who are in danger and otherwise the medical personnel should be only there to help the runners complete their race.

Relevant Notes from Day 2

- Dr. Hew-Butler pointed out that in South Africa, she used to pay $2 to 3 to run a marathon and nobody expected any medical care. She made the very interesting point that the more runners pay for a race, perhaps, the more medical care they expect. She also says if runners pay less for a race and don’t expect anyone to help them in an emergency, they will tend to be a lot smarter and careful with the way then run.

- Along those lines, and an additional point from Day 2 of the conference, was in races like Western States and other even more remote wilderness races, defibrillators for runners with cardiac arrest are not available everywhere on the course. It is not practical. So, unlike at a large city marathon where defibrillators and health-care workers are omnipresent, a runner with cardiac arrest in a remote ultra has a low chance of survival. Runners with a history of heart disease need to take this into consideration when signing up for races.

- This year at Western States, all runners will receive a printout of their post-lab tests. Dr. Hoffman stated that this was just for the runners’ information and not by any means a necessary part of medical care, but since these values are collected for research, the runners will also receive them.

- For the first time there will be no pre-race medical check. Weights will be taken for research purposes.

- If any ultrarunners are interested in participating in a research study about health in endurance athletes, you are invited to take this survey. The primary results from this study have been published.

For ultramarathon race directors and medical volunteers, there is an organization called the Ultra Medical Team that helps to establish medical-care teams for ultras.

For ultramarathon race directors and medical volunteers, there is an organization called the Ultra Medical Team that helps to establish medical-care teams for ultras.- At the end of the day, there was general a consensus that this conference should be held again next year. I had the chance to ask Dr. Marty Hoffman about this afterward and he said he is planning to hold it again and that there is will be more than enough material to have entirely new lectures and presentations in 2015.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Phew. Did you make it this far? If so, what are your first impressions from the conference’s report?

- What information were you most interested in, and what applies most to your personal running experience?

- In what areas do you hope more research will take place? In other words, where do you think vacancies currently exist in our knowledge about the science of our sport?

- We may publish more in-depth reports from this conference. If so, what presentations would you like to hear more about?

For ultramarathon race directors and medical volunteers, there is an organization called the Ultra Medical Team that helps to establish medical-care teams for ultras.

For ultramarathon race directors and medical volunteers, there is an organization called the Ultra Medical Team that helps to establish medical-care teams for ultras.