When Whiley Hall reaches the summit of the 13,500-foot Telluride Peak in August, during a casual training run with me tagging along, she pauses to identify the San Juan Mountains encircling us as if she’s introducing old friends.

“That’s Kismet, Cirque, Teakettle, and Coffeepot,” she says, pointing northward to the peaks next to the better-known, 14,150-foot-high Sneffels. Her long blond hair flows out the back of a trucker cap that says Ouray Ultras. “And there are the Reds,” she says, looking westward toward Ouray at a trio of peaks streaked rusty red from iron. Then she turns southward, toward Silverton, to a line of teeth-like peaks in the distance, “and that’s the Wemi,” short for Weminuche Wilderness, which has dozens of remote and difficult peaks rising above 13,000 feet.

Hall, a 30-year-old ultrarunner with podium potential at the September 17 Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile, knows these peaks intimately because she’s summited very nearly each and every mountain in view over the past four summers, part of her massive goal to bag every peak 13,000 feet or higher — 13ers, as they are called — in the whole state of Colorado.

Training for Ultramarathons by Summiting Hundreds of High Peaks

Let these numbers sink in: She’s summited 553 of Colorado’s 767 ranked and unranked 13ers, according to the website 14ers.com. (“Ranked” means a peak has 300 feet or more of prominence; “unranked” means the peak is a bump that rises less than 300 feet along a ridge.) When you add in the whole United States, she’s topped 1,671 unique peaks as of this writing (the total rises almost daily).

“She knows Colorado’s mountains like the back of her hand and would rather be miles away from civilization on some God-forsaken lump of broken rock than anywhere else, which isn’t to say that she’s a curmudgeon, but rather that the mountains are where she’s at her best,” says her peak-bagging mentor and adventure buddy Ben Feinstein. “She’s a great climber and athlete.”

Though a handful of women on record have done more peak bagging in Colorado than her, Hall is one of the very few females involved in the niche pursuit. “Women at best make up five percent of dedicated peak baggers,” says Greg Slayden, creator of the site peakbagger.com. To do what she’s doing, he explains, involves “a staggering number of peaks. You find yourself climbing a lot of peaks that most people wouldn’t want to climb, because they’re boring, or they’re out of the way, or they involve a lot of suffering and bushwhacking. You have to be really focused on the goal of climbing all the peaks to go after some of these obscure summits.”

In early August, Hall’s combined skills of summiting, navigating, and ultrarunning enabled her to win and set a course record at the extreme and little-known High Five 100 Mile, which makes the Hardrock 100 look like beginner’s fare. The High Five, started in 2019, summits five 14ers — peaks taller than 14,000 feet — with no set route, no course markings, and no aid stations, just a few checkpoints.

Before 2021, only one woman had ever finished it. This year, four of the 12 finishers were female, and Hall finished first in 33:30 — just one hour, 14 minutes after the course-record-setting leader, Chris Marcinek.

For “recovery” the next day, she summited a 13er with some 6,000 feet of climbing, much of it off trail.

“It’s really crazy, she doesn’t tire. She never ceases to amaze me, she’s so mentally strong and never complains,” says Hall’s mountain-running friend Erich Owen, who finished behind her in the High Five. “She’s just really good at technical terrain. She can blaze down 50-degree-angle scree fields like an antelope, super efficient and strong, and very knowledgeable on navigation. She can pick really great lines.”

Hall kindly guided me up Telluride Peak to help me scout out the toughest segment of the 40-mile Telluride Mountain Run, a race she won in 2019. When I admit how the loose-rock scrambling and exposure on both sides of the fin-like ridgeline makes me tense up and tremble with fear, she says in a heartfelt way, “I love this part. I wish the whole route could be like this.”

Hall reveals an entirely different kind of fear: social anxiety. She is reluctant to be profiled for this article because she doesn’t seek attention. “I want to live under a rock,” she says, half-joking.

Her reply to my first text reads, “Normally I don’t like the idea of anyone knowing who I am, but my friends are telling me I need to get over that and face some fears and just do it. This is just a written piece, yeah? That makes me much less nervous than a podcast.”

Even her real name is private. She started calling herself Whiley at age 19 and legally adopted it three years ago. “I threw out all this bad stuff with the old name,” she explains later as she opens up a bit about her background. She also got a tattoo in college, on her right shoulder blade, that peaks out from under her tank top and reads, “Corinthians 10:13,” a biblical passage that has to do with managing temptation. She says it’s a verse that reminds her, “no matter how low you get, God is there to help you get out of it.”

After Hitting a Low, Finding Redemption On a Summit

Hall grew up in Holland, Michigan, next to the shore of Lake Michigan, to parents she lauds as loving and encouraging. They told her and her two older sisters to do “whatever we’re passionate about and makes us happy. They’re not very athletic, but I’ve always been drawn to that,” she says. “I’m a high-energy person, and my outlet was doing these activities.”

She started running as a kid and competing as early as third grade, then ran cross country and track through high school. At 15, she began to develop a stress fracture in her hip, and when she fell during a track meet, the hip fractured fully and required three screws to repair. The injury left her with a slight leg-length discrepancy, but “I haven’t had any issues with it, so I’m really lucky.”

Hall moved from Michigan to Colorado with her family after high school graduation, and her dad worked in private security near Aspen. Later, her father transitioned to a job as a sheriff’s deputy in Steamboat Springs, where her parents live now and where Hall calls home when she’s not living in her truck during peak-bagging months.

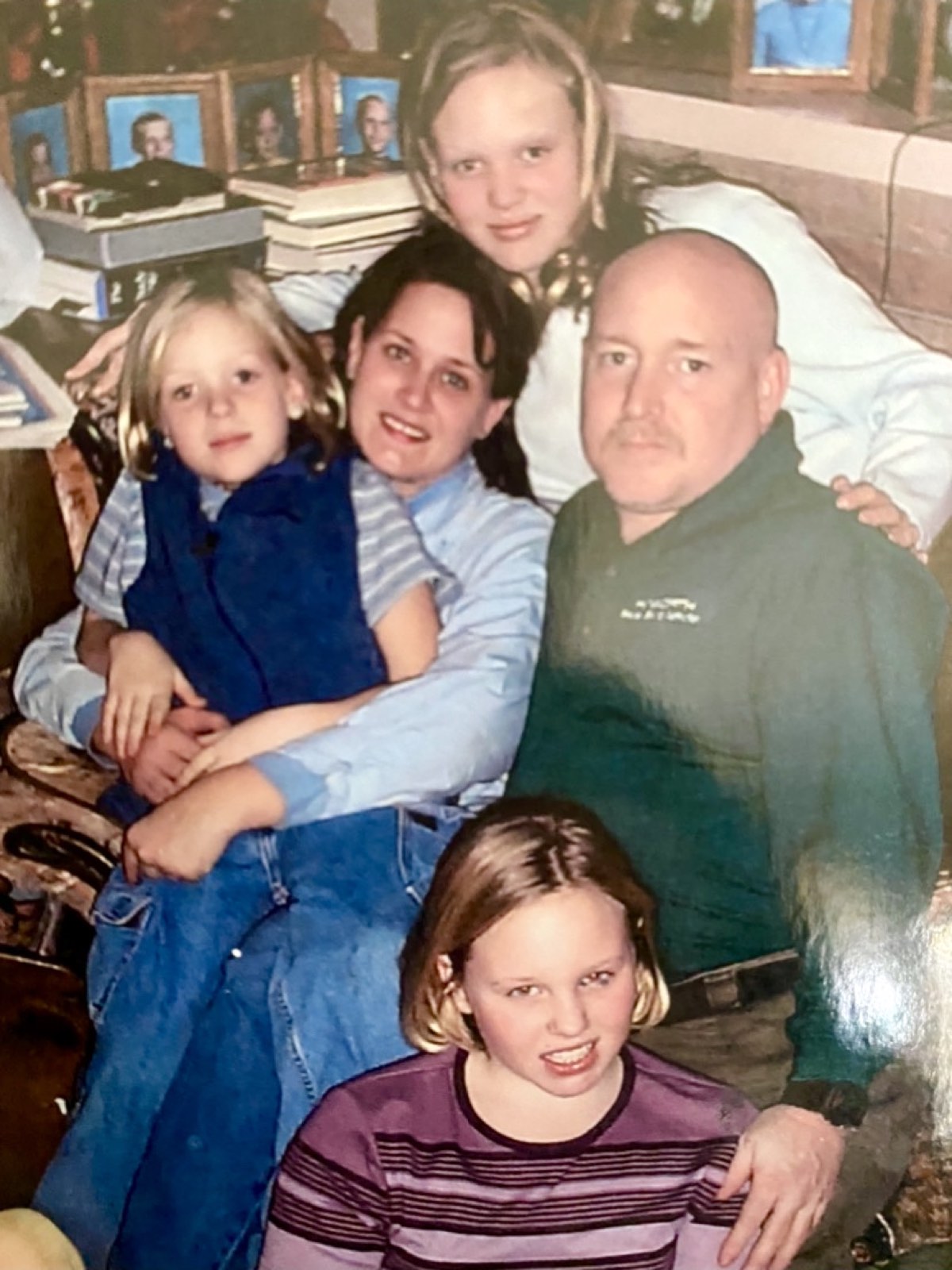

Whiley’s family includes Whiley (at left), parents Carrie and Tom, older sister Wesley (at bottom), oldest sister Whitney (at top), and younger sister Carolee (not pictured). Photo courtesy of Whiley Hall.

For college, Hall headed to the University of Colorado Boulder. “I never really wanted to compete through college,” she says, when asked if she ran cross country after high school. “I thought about it, and did a tryout, but didn’t like how little freedom the girls on the cross-country team had; they didn’t have a normal college life. Plus, I would’ve been back of the pack.”

As it turned out, Hall took “normal college life” to the extreme during her freshman year in 2009, and she lost touch with running in the process. “Freshman year was a waste and didn’t count for much. I was partying pretty hard and doing drugs and stuff, and I gained a lot of weight — I was 195 pounds,” she recalls. “I was pretty sheltered growing up, and when you have all that freedom in a new place, you can get into the wrong crowd, and that’s basically what happened.”

She made a break from that unhealthy first college year by landing a job as a counselor at a youth church camp in the small town of Como, Colorado, 10 miles up the road from Fairplay and at the base of the 12,100-foot Little Baldy Mountain. Little did Hall realize at the start of the summer of 2010 that Little Baldy would change her direction in life.

“Every week we’d take the campers up to the summit of Little Baldy, so it became this kind of spiritual connection for me, and when I went up to this summit, it was always a huge challenge,” she says.

The camp in Como had no cell coverage, so her summer job also helped her unplug from the then-new-world of social media and the anxiety-producing pressure that it can generate. “I thought that was really healthy,” she says of going offline and living at the camp, “and it forced me into these places that made me deeply search myself and challenge myself in different ways, and to get to know myself.”

During that summer, she summoned the courage to hike with the other camp counselors up her first 14er, Pikes Peak. “It was the hardest thing in my life, because I was overweight, and we were backpacking. I felt like death,” she says, laughing. But she was hooked.

Whiley (center) on the summit of Pikes Peak in 2010 with two camp counselor coworkers. Photo courtesy of Whiley Hall.

As many new peak baggers do, she set her sights on tackling the list of 58 ranked and unranked Colorado 14ers. She made steady progress from 2011 through 2017, but her ability to climb mountains was limited by not owning a car, so couldn’t easily get around the state. When she got a vehicle in 2018 and finished the final 14er on the list, she opened her eyes to all the 13ers waiting to be climbed. Day after day, from spring through late fall in 2018 and 2019 (and occasionally on snowy days of winter), she knocked off scores of peaks, often bagging several in a single day.

Her goal of summiting every ranked and unranked 13er in Colorado — while making side trips to summit mountains in other states, and sometimes repeating peaks she’s already climbed just for the love of it — is difficult to describe because the task is so monumental. Her friend and climbing partner Luke Gangi-Wellman — also an up-and-coming mountain-running phenom who set a course record at this year’s grueling John Cappis 50k above Silverton — sums it up this way: “She’s trying to climb over 700 mountains, most of which have no trail and require extensive route-finding skills, many of which are highly technical and dangerous,” he says. Plus, “she’s trying to do it quickly, efficiently, and with as much running as possible.”

From left to right are Maggie Guterl, Marisa Watson, and Whiley in the La Garita Wilderness in 2020. Photo: Maggie Guterl

Last summer, when the pandemic shut down races and most normal activities, Hall went for the record of the most consecutive days bagging a new ranked peak (including peaks lower in elevation than 13,000 feet). The previous record was 92 days, and Hall got to 146. That means every single day, from March 28 through August 20, she summited a unique ranked peak. On several days, she failed to summit the peak she intended due to safety concerns, so she had to turn around and go climb a different and new-to-her ranked peak that day. She had to break the streak after 146 days to return to an in-person teaching job.

Asked how she affords her peak-bagging lifestyle, and what she does for work, Hall explains that while in Boulder, where she graduated in 2014 with a degree in Environmental Studies and Psychology, she worked and saved a good amount of money as a law librarian while also doing some post-graduate studies in neuroscience. Then she moved back to Steamboat Springs to save rent money by living with her parents, and for two-and-a-half years, she worked as a paraprofessional during the school year, a classification of a teacher who works one on one with special-needs students.

What drives her to chuck the normal life of a young professional for the sake of scaling mountains during the better part of the year? “It’s a sickness. I don’t really know,” she laughs. “I just love being outside and moving my body through the mountains. And, not many people have finished the entire 13ers list. For me, having those goals is incredibly important, whether it’s in a race, or with peaks. I’m very goal-driven.”

According to her friends, however, her intensity and her goals don’t get in the way of being safe or having fun. “She does it all with joy and love in her heart,” says Gangi-Wellman. “Her goals are organized with lists and objectives, but she will always prioritize fun over work.”

From left to right are Maggie Guterl, Meghan Hicks, Marisa Watson, Whiley, Missy Gosney, and Hannah Green on Bear Peak in 2020. Photo: iRunFar

“She doesn’t take herself too seriously,” says her ultrarunning friend Maggie Guterl, who met Hall when they bonded over suffering through the 2017 Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile. “She’s a kind and welcoming person when you meet her, but definitely enjoys her solitude.”

Guterl recalls how Hall cared for her when the two were on an epic outing in late 2019 and Guterl was struggling with asthma. Hall suggested they cut back their goals for the outing and return to camp early, even though that meant not reaching peaks they had planned to summit. “She told me she was perfectly content with what we had done and urged me to agree to go back to camp and call it a night,” Guterl recalls. “She is not crazed by summit fever; she just wanted me to be OK, and summiting everything on her list that night wasn’t this whole ‘must-do-at-all-cost’ type of thing.”

Racing With the Hares

Hall has run few ultras other than Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile, where she placed fourth in the “Hare” (elite) division in 2019 in 24:58. This race motivates her, she says, for a few reasons: to gain a qualifier to enter the Hardrock 100 lottery, which she’d like to race someday; and to win money, which she needs on her tight budget. This year, the race awards $15,000 to the winner and additional prize money through seventh place. During the summer and fall peak-bagging season, when Hall takes a leave from work, “all my money goes to food and gas.”

Beyond those practical reasons for racing this mountainous 100 miler, Hall is driven to return to improve her time. She ran the Run Rabbit Run 50 Mile as her first ultra in 2016. The following year, she ran it as her first 100 miler and finished, but after the 30-hour Hare division cutoff, hence it’s listed in her results as a DNF. “It was very demoralizing and beat me down,” she says of the struggle-fest of her first 100 miler, “but I learned a lot.”

While Hall and her parents Carrie and Tom Hall after the 2018 Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile. Photo courtesy of Whiley Hall.

The next two years, she returned and improved. (The race was canceled in 2020.) This year, “I want to cut another two hours off my time. My goals are usually ambitious.”

She also wants to return to the High Five 100 Mile in 2022 and win outright with a new course-record time. “I do this with every race — when I’m reflecting on it, I think of ways of dramatically improving. It’s a huge draw, comparing those past times with how I’ve improved, not just with time but also mentally. Even if I don’t beat my time but I feel my mental game was better, I take that as a win.”

Still, she prioritizes peak bagging and resists training for ultras in any traditional way. “Rest day, taper — she doesn’t know these kinds of words,” says her friend Owen.

Adds Guterl, “Peak bagging keeps her ready for ultras naturally. That’s where her true passion lies. … She probably won’t be signing up for the Western States 100 anytime soon. Too much running, not enough mountains. I’d love to see her give the Barkley Marathons a try.”

Next year, Hall likely will try to fit in an attempt at the Nolan’s 14 fastest known time amid working on her goal of summiting all ranked and unranked Colorado 13ers.

Her free time in the mountains is about to get more limited, however. After Run Rabbit Run 100 Mile, she’ll resume living at her parents’ house to help care for a grandfather with dementia, and in January, she plans to go back to school to earn a master’s degree in clinical mental health counseling. “I know a lot of people who deal with mental health issues, and I have my own that I’ve struggled with, so I’m very attracted to that career,” she says. “Since I’m going back to school, my peak bagging is going to go down.”

Asked where she’d like to establish a clinical practice, Hall says, “It would absolutely be near the San Juan Mountains. That’s what I consider my heartland.”

Would she ever say “enough is enough” on her 13ers goal? “I don’t think so,” she says, and plus, she wants to traverse and summit so many other mountains under 13,000 feet. “I want to do everything in Colorado” — meaning, climb every mountain — “so that’s going to take quite a while.”