When I was 15 years old, I fell in love with cross-country skiing. And when I say fall in love, I mean head-over-heels, jump-in-with-two-feet love. I bought my first heart-rate monitor strap and started to keep a detailed training log that included things like total training hours, how many minutes I skied at different intensities, and my morning resting heart rate. Combined, these tools helped me monitor my training load and recovery.

In the past 15 years, the recovery industry has blown up with new tools, gadgets, and modalities to help you recover better, faster, and more efficiently. Some of those tools are phone applications and wearables that specifically track heart rate variability. So, what the heck is heart rate variability, and is it potentially a tool worth adding to our training toolbox?

What is Heart Rate Variability?

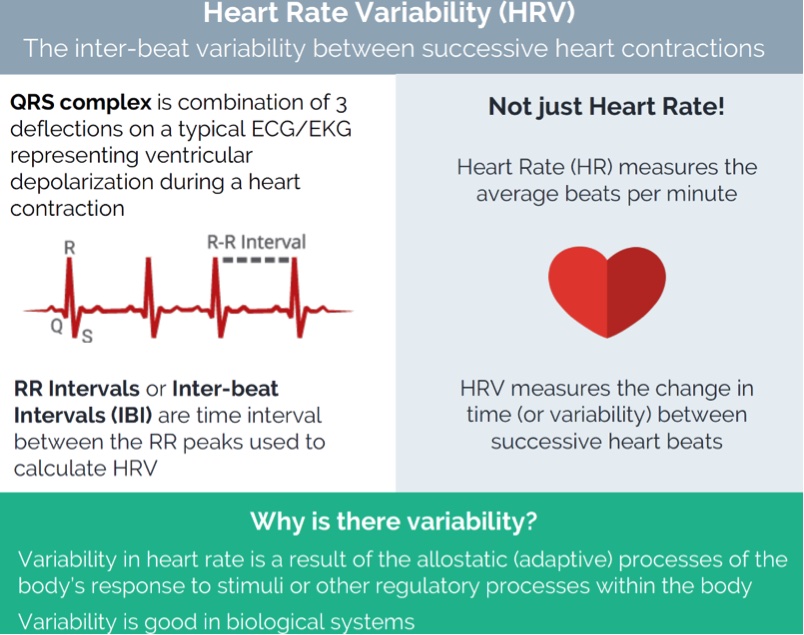

Very simply, heart rate variability (HRV) is the subtle variation in a series of beat-to-beat measures of the heart.

Explained in more detail, it’s the variation between the peak of the R wave in the QRS complex of your heartbeat as interpreted on an electrocardiogram (EKG) (1). This is referred to as the R-R interval. Without doing a deep dive into the form and function of your heart, it’s important to understand that your heart utilizes a pretty cool electrical system to pump blood around your body. Nodes in your heart generate electrical stimulus that causes your ventricles (the lower portion of your heart) to contract and pump out blood. Each time that electrical current passes through the ventricles and your heart is at its most contracted, we see a R wave on an EKG, and each of these contractions of the ventricles represents one heartbeat.

Our hearts are not perfect metronomes. If you were to take your heart rate right now, by feel, you might notice that each beat is not perfectly spaced. So while your resting heart rate (RHR) might be 60 beats per minute, the time in between those beats is in constant flux. This variability is a good thing! It means your that nervous system, specifically your cardiac autonomic nervous system is doing its job, constantly adjusting to internal and external stimuli maintain homeostasis — your body’s happy place.

Although hype has developed around HRV in the past decade, scientists and physicians have been utilizing it as far back as 1847 as a means of monitoring cardiac arrhythmias and it has helped to form general relationships between variability in cardiac rhythms and disease (3). HRV is truly an old metric that has been given new life and meaning by the athletic world.

An explanation of the differences between heart rate and heart rate variability, as well as why heart rate variability occurs. Image: Chirohub.com.au/2020/01/14/heart-rate-variability-hrv-your-stress-is-measurable

Heart Rate Variability and the Nervous System

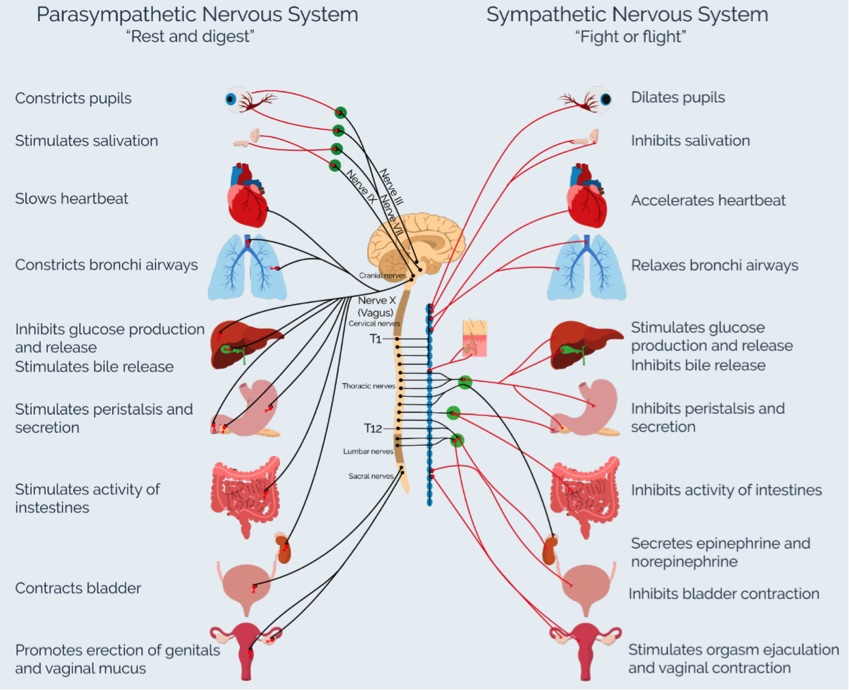

Your nervous system is divided into two major systems: the central nervous system which is made up of the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral or autonomic nervous system which made up of nerves that branch off from the spinal cord and extend to all parts of your body. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is further divided into two parts: the parasympathetic nervous system which responsible for “rest and digest,” and the sympathetic nervous system which is responsible for “fight or flight” (4).

The parasympathetic system is responsible for getting things back to a normal state of rest, repair, adjust, and remodel by doing things like slowing down our heart rate, decreasing our blood pressure, and dilating blood vessels (which increases blood flow and circulation), all of which sends energy back to where it came from.

The sympathetic system is responsible for the opposite, focusing on mobilizing energy by increasing your heart rate, raising your blood pressure, diverting blood flow to working muscles, and releasing sugar into your bloodstream to fuel those working muscles efficiently.

These two systems work in tandem to coordinate our response to physical, psychological, environmental, and other stresses, and to maintain that always-shifting internal balance. There is a component of the ANS that specifically targets cardiac tissue, and the parasympathetic branch of it ultimately has the largest effect on HRV, resetting, restoring, and allowing us to rebuild and recover from different types of exertion. This makes HRV an efficient (readings take one to five minutes), inexpensive (you can utilize scientifically validated free phone applications), and non-invasive (utilizing wearables or even just your phone camera light) tool to gauge recovery status and how well an athlete is adapting to their overall stress load, which means the combination of run training and other life stresses (2).

An explanation of how the parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system serve as your “rest and digest” and “fight or flight” responses respectively. Image: Chirohub.com.au/2020/01/14/heart-rate-variability-hrv-your-stress-is-measurable/

Heart Rate Variability for Endurance Training and Performance

If HRV is a tool that we can use to gauge recovery, fatigue, and training readiness, then how exactly do we use it? Like any metric, it’s important to establish a baseline, collecting data points that let you know where your personal normal sits, the same thing you would do to establish a baseline for RHR or iron levels, for example.

Generally speaking, higher HRV is considered a positive thing, and lower HRV represents a nervous system that isn’t being as responsive as it could be. Similarly, lower RHR is considered a positive response to training and higher RHR is considered a sign of fatigue.

But there is a still a lot of nuance in your cardiac response to stress that is not always as straightforward, leading to complications in how to interpret these metrics:

- A classic positive example: An increase in HRV and a decrease in RHR generally means an athlete is coping well with training and life stress.

- An example in which one metric says things are okay and one says something is off requires further context: An increase in HRV and an increase in RHR is generally a sign of accumulated fatigue (or potentially that you are getting sick) unless it at the very beginning of a short training block.

- An example in which it seems bad but is situationally fine: A decrease in HRV and an increase in RHR is generally a sign of accumulated physical and mental fatigue, unless an athlete is tapering and then it could be a positive sign for readiness to perform.

- An example in which one metric says things are bad and the other says things are okay means that further context is needed: A decrease in HRV and a decrease in RHR is generally a sign of prolonged low intensity, high volume training (or large changes in life stress) and if it cannot be reversed with rest can be a sign of being in an overtraining state.

The 2021 UTMB men’s leaders demonstrate their fitness in a fast start to Saint-Gervais, about 20 kilometers into the race. Photo: iRunFar

This might sound a bit like reading tea leaves, but akin to understanding any individual physiological metric, context is important, and one value or metric on its own almost never paints a complete picture. For fun, here are even more examples. A decrease in HRV that only lasts a day or two may be due to a particularly strenuous training session and is not an indicator of disaster. And an increase in HRV could be in response to illness as your immune system suddenly ramps up instead of a sign of readiness. What this means is that you need to take your time to understand your personal nuances to gain meaningful insight.

The next trick is, how are you measuring HRV? There are many different methodologies that researchers have tried to use to best assess HRV in athletes, and it’s argued that the mismatch in methodology is why so much of the research has conflicting results (2). What we do know is that your ANS is highly sensitive to environmental conditions like light and noise, so utilizing night readings from your final sleep cycle using wearables or taking readings first thing upon waking via phone applications will produce your most consistent and accurate HRV values (2). However, there is additional research that suggests if you are trying to utilize HRV to avoid overtraining, taking measures upon waking are better because they highlight a diminished parasympathetic response that overnight readings don’t seem to pick up due to specific hormones which are present first thing in the morning (specifically cortisol) (5).

Finally, it’s important to remember that just like the variability between your heartbeats, there is variability in your day-to-day and even inter-day HRV readings. In practice, this means a one-day reading does not have as much value as evaluating changes in HRV by looking at trends over time. One bad day of decreased HRV (especially if your RHR is normal) is not worth worrying about, but if that trend continues, that’s a sign your body would welcome some rest.

You’re probably wondering, are there other things that are known to positively or negatively impact HRV? Two of the biggest influences on HRV are age and endurance exercise. The literature shows that independent of health and activity, our HRV declines as we age which is a response to the slowdown in the reactivity of our nervous system. Endurance exercise, the reason we’re all here and something we might do to excess, can help slow that effect of age and is generally good for HRV. These two things combined have spurred a lot of research into what some think is the fountain of youth, with HRV at the center of it all.

Other practical pieces of your life that will improve HRV are things that increase the activation of your parasympathetic nervous system like relaxation exercises, mediation and breathing practices, getting quality sleep, and working with your circadian rhythm (6). Conversely, things that negatively impact HRV are those that decrease activation of your parasympathetic nervous system like exposure to low levels of chronic stress, poor sleep quality, disruption of circadian rhythm (late meals, irregular bed time), and moderate alcohol consumption (considered two drinks for males and one for females) (7).

Meghan Hicks running in Colorado. A watch like hers can be used to monitor heart rate both during a run and while at rest. Photo: iRunFar

What Do I Need To Know?

If you utilize HRV as a training tool, keep these key points in mind:

- Take readings frequently. To effectively utilize HRV as an endurance athlete, it’s best to aim for taking morning or nighttime HRV measures three to four times a week, if not daily. This not only allows you to establish a baseline, but also allows you to better identify subtle changes over time.

- Create consistency. To remove confounding variables (a variable that influences the variables you are actually measuring), try to take your recordings at the same time every day. If you utilize a wearable, it should do this for you, but if you are taking your own readings via a phone application, be consistent in when you measure it.

- Don’t use it alone. Like any training metric, HRV is not perfect and is best when used in conjunction with other data. Other information to help you make an informed decision with HRV readings include RHR, training load, sleep volume and quality, as well as other subjective measures like mood.

- Don’t let one bad day throw you off. HRV works best when evaluating trends over time and even utilizing weighted rolling averages (the most recent data is most important but the rest of the data still holds weight). One day of decreased HRV or increased RHR does not spell disaster.

Call for Comments

- What heart rate monitor do you have in your training toolbox?

- Do you base your training intensity and volume around your heart rate variability, among other factors?

References

- Makivić, B.; Nikić Djordević, M.; Willis, M. Heart Rate Variability (HRV) as a Tool for Diagnostic and Monitoring Performance in Sport and Physical Activities: Journal of Exercise Physiology Online. 16: 103-131 p. 2013

- BUCHHEIT, M. Monitoring training status with HR measures: do all roads lead to Rome? Front Physiol, v. 5, p. 73, 2014. ISSN 1664-042X.

- BILLMAN, G. E. Heart rate variability – a historical perspective. Front Physiol, v. 2, p. 86,2011.ISSN,1664-042X.

- Singh, N., Moneghetti, K. J., Christle, J. W., Hadley, D., Plews, D., & Froelicher, V. (2018). Heart rate Variability: An old metric with new meaning in the era of using mHealth technologies for health and exercise Training Guidance. Part One: Physiology and methods. Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review, 7(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.15420/aer.2018.27.2

- Hynynen E, Uusitalo A, Konttinen N, Rusko H. Heart rate variability during night sleep and after awakening in overtrained athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Feb;38(2):313-7. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000184631.27641.b5. PMID: 16531900.

- Kemp, A. H., & Quintana, D. S. (2013). The relationship between mental and physical health: insights from the study of heart rate variability. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(3), 288-296

- . Karpyak VM, Romanowicz M, Schmidt JE, Lewis KA, Bostwick JM. Characteristics of heart rate variability in alcohol-dependent subjects and nondependent chronic alcohol users. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014 Jan;38(1):9-26. doi: 10.1111/acer.12270. Epub 2013 Oct 11. PMID: 24117482.

- Pietilä J, Helander E, Korhonen I, Myllymäki T, Kujala UM, Lindholm H. Acute Effect of Alcohol Intake on Cardiovascular Autonomic Regulation During the First Hours of Sleep in a Large Real-World Sample of Finnish Employees: Observational Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(1):e23. Published 2018 Mar 16. doi:10.2196/mental.9519