If you know the annual Leadville Trail 100 Mile in Colorado, then you know the Hope Pass aid station is one of the places runners fuel and water up during the race. Runners hit this aid station twice during the out-and-back event, once on the outbound at about mile 43 and again on the inbound at mile 57. Perched exactly at tree line, where alpine tundra meets conifer-dominant forest at 11,800 feet altitude and about 700 vertical feet below the race’s high point of Hope Pass, the aid station has become something of an icon in the trail running and ultrarunning community.

But an aid station near Hope Pass was not in the blueprint for the Leadville 100 Mile when the race launched in 1983. On Hope Pass, runners are particularly vulnerable to Colorado’s high-alpine weather, which can rapidly swing from sunshine to snow to thunderstorms all in a couple of summertime hours.

“In the early years, it was not an official aid station. A bunch of caring people wanted to make sure the runners were well cared for and safe. That was the genesis of the Hope Pass aid station,” said Merilee Maupin, co-founder of the Leadville 100 Mile.

Late llama farmer Dee Goodman spearheaded the high-elevation aid effort, located some 2,500 feet above the valley floor. Merilee and Leadville 100 Mile co-founder Ken Chlouber were both burro racers in the 1980s, and they befriended Goodman through the burro-race circuit, which was intertwined with llama races.

“We told Dee what we were doing with the race, and he said, ‘I think the runners need a place up high for aid and safety. On his own, he started taking his llamas up and talked some of his friends with llamas into doing the same thing,” said Merilee.

The original rogue crew was comprised of about six llamas and 10 volunteers, recalled Vicky Foster, a former Hope Pass aid station captain and a volunteer of more than 30 years.

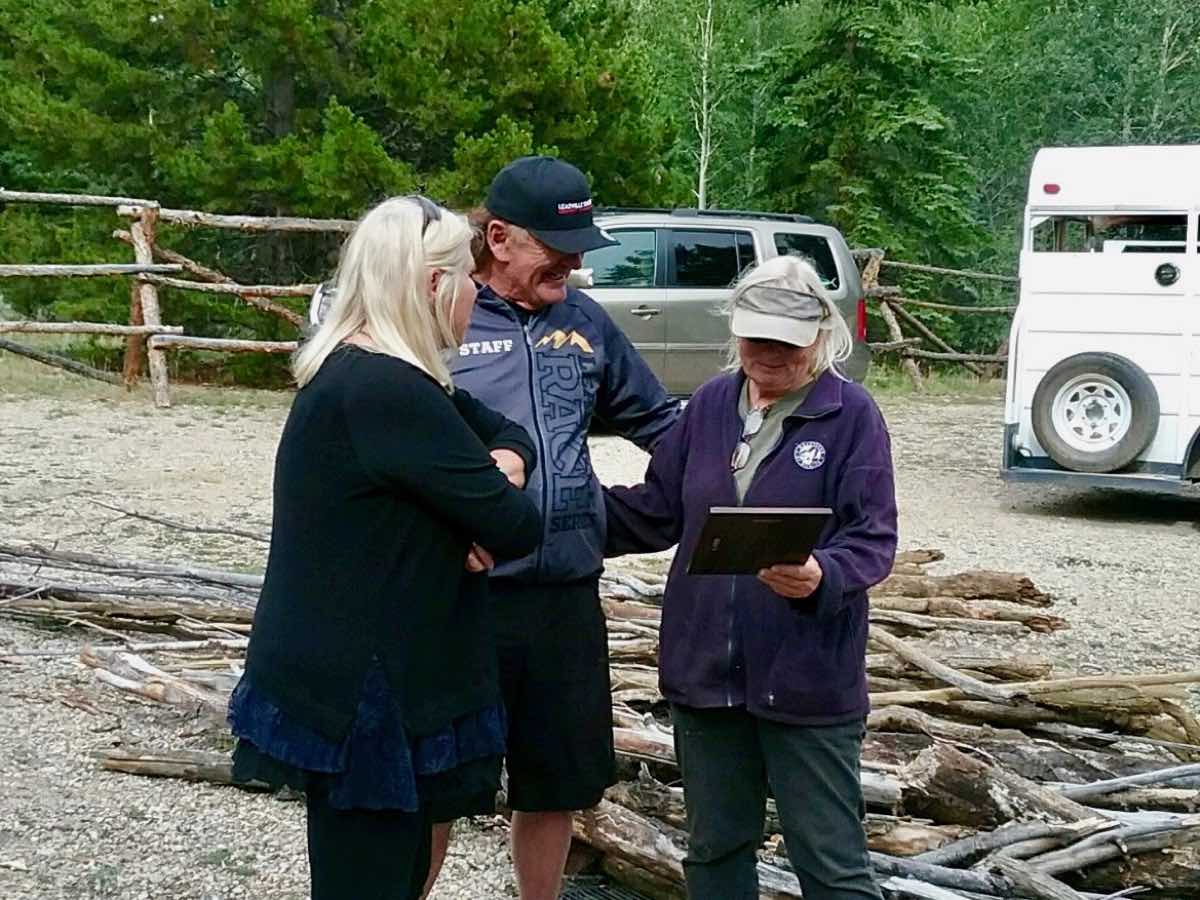

Vicky Foster, a 30-plus-year volunteer at the Hope Pass aid station during the Leadville Trail 100 Mile. Here she is volunteering at Hope Pass in 2017, her final year at the aid station. Photo: Alexa Metrick

Alongside Dee, “A [then] local Leadville emergency medical technician, Jude Schuenemeyer, said, ‘This is the most dangerous spot in the race, and there needs to be someone up there.’ Jude wanted to start the renegade aid station and needed someone to help him get gear up there,” said Vicky, who got involved a few years later, in 1987, when a llama packer paced a racer, instead, and needed a fill-in. Also a llama packer, Vicky, then 40 years old, was connected with the llama community. She—and her llama, Stretch—heeded the call.

“Jude was right. It can be very exposed on Hope Pass. We’ve had people get lost coming over the hill, particularly on the way back, or come in hypoglycemic. Lots of different things can happen,” said Vicky.

In those ‘unofficial’ early years, Vicky packed a first-aid kit and food to share with the runners. There wasn’t a medical or nutrition tent. The crew hand-pumped water out of the nearby creek with Foster’s Katadyn water filter.

“At first, a little bit of warm ramen was all we gave the runners. So, I always sell myself as the best darn ramen chef on the mountain. But there are a couple of repeat runners who love the instant mashed potatoes, as well—and it’s a great potato soup if you mix them,” said Vicky, who was a 10-kilometer- to marathon-distance runner for many years. Today, at 71 years old, she opts for backpacking and hiking trips over races. She also recently gave up her annual pilgrimage to the top of Hope Pass.

Before Vicky retired from her leadership duty, at the close of the 2017 race, Merilee and Ken surprised her pre-race with a plaque at the aid station’s staging ground at the bottom of the pass.

“We thanked Vicky with an award for her many years of service, and her dedication to the racers and the race,” said Merilee. “Vicky’s ‘llama mom’ instincts became her ‘runner mom’ nature. She mothered the many, many runners who came through that aid station over the years,” she said.

Gary Carlton, current Hope Pass Aid Station team captain and coordinator, took over Vicky’s responsibilities. Gary, another longstanding volunteer, has led his llama herd up the pass since 2003, when Vicky first recruited him.

“Hope Pass is a beautiful hike and gorgeous place to be, but it’s about the runners. The runners early on realized that the ‘Hopeless’ [the aid station’s nickname because it’s at a difficult place on the race course] crew was different. We were a community ourselves, and so many volunteers come back year after year,” said Vicky. Back in 2002, Gary became the race coordinator for the Pack and Walk Llama Race in Fairplay, Colorado (a title he held until 2017). He managed everything from registration and permits to insurance and course set-up.

Vicky had an inkling that Gary would love the experience and community on Hope Pass, too. She was right.

“When you get to the top of Hope Pass and look around, the place itself is the first thing that really catches you. And then, the runners during the race are just awesome,” said Gary, who has made the journey up Hope Pass for 15 years. The 2019 race, held on August 17 and 18, will be his 16th year in a row as a volunteer at the aid station.

“Gary is a face-to-face type of human, and he’s absolutely vital to the success of our event,” shared Rich Naprstek, Leadville Race Series volunteer coordinator, via email.

Gary arranges all of the aid-station supplies and then oversees the week-long process, which has grown to include 50 volunteers and 30 llamas—including five of Gary’s personal pack animals—that haul 3,000 pounds of food and gear up the pass. The commitment takes a month to fulfill including a week in the field for the event.

“I go to Leadville and Twin Lakes on the Sunday before the race. We go to the warehouse on Tuesday to pick up all the gear, then head up the mountain on Thursday. We come down on Sunday, after the race,” he outlined.

On race week, a core group of a dozen folks and llama packers ascend the pass on Thursday with Gary. A handful of those folks have volunteered alongside Gary for 15 years. Golden High School in Golden also brings a group of 15 kids each year. Then, two shifts of 15 volunteers arrive at 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. on race day.

“Hope Pass always feels like such a happy oasis. The energy of the high schoolers who volunteer there buoys my spirits. They always seem like they’re having a great time,” said Liza Howard, a two-time Leadville 100 Mile champ and coach providing guidance through Sharman Ultra Endurance Coaching. “I didn’t know there would be llamas at the Hope Pass aid station the first year I ran Leadville, and I was worried I was hallucinating when I saw them. Now, I always look forward to seeing them. Hurrah! Mountain llamas!” she said.

The llamas seem to love the entire experience, too.

“Llamas don’t get tired of the race. They seem to enjoy it. Mine will be a mile away from the gate, in the creek bottom, and when I whisk them up to the front gate, they know it’s time to go and they run. They’re excited,” Carlton described.

Over the years, the aid station has evolved and drastically improved. “Technology keeps making things easier. We have a self-contained, battery-operated, water-filtration system. Back in the old days, it was completely run by motorcycle batteries. Now, we use solar power during the day, for the water filter, and other things around the aid station,” said Gary. Using solar panels eliminates 150 pounds of battery weight from the haul. When the sunlight fades, they can still use the motorcycle-battery system. The ingenious setup was developed by Gary’s friend Jim Osmun, another longstanding volunteer who has passed.

Water is a big deal at high elevation: The aid station goes through 500 gallons on race day while the runners come through from about 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. After the water is filtered, it’s chlorinated and then hauled a quarter of a mile by the llamas, two jugs at a time, from Willis Creek to the aid station. The train of llamas goes all day long.

“When I first started going up Hope Pass, the [race organization was] giving us two-liter bottles of coke for the runners. But the carbonation would upset their stomachs. So, the night before the race, we’d loosen the caps on every one of the bottles. Vicky and I thought, Let’s just buy coke syrup and make it up here. The race series said, ‘We can’t do that, because it’s not officially coke.’ Vicky and I said, well, let’s call it something else—like ‘Hope Pass Cola.’ We’ve been doing that for 12 years now. Instead of 200 two-liter bottles, we bring up two gallons of coke syrup,” said Carlton.

One of Vicky’s favorite memories was when a helicopter pilot landed in the high meadow adjacent to the aid station. The lift was for a T.V. crew filming the event but the pilot surprised the Hope Less squad with a pizza delivery. Unfortunately, the weather kept him from taking off for a long time.

“He couldn’t get out of valley for darn ever. We got so tired of hearing that helicopter that the whole team mooned him. It was one of the funniest times and I was a lot younger then,” said Vicky.

Vicky (right) receiving her volunteer-service award from Merilee Maupin and Ken Clouber, Leadville 100 Mile founders, after her final year of service in 2017. Photo: Gary Carlton

Hardship has surfaced for the Hopeless crew, too. When Dee passed away suddenly, in 2007, from diabetes-related causes, Vicky adopted his role. That year, before the race commenced, the aid-station community spread Dee’s ashes from the top of the pass.

“Dee was a very close friend and a very flamboyant llama person. He was a wild man!” said Gary, who also recalled obstacles that paralleled the race’s growing pains, in 2010, when Life Time Fitness purchased the race.

“When Life Time Fitness tried to maximize the capacity, there were 1,200 entries. Our aid station couldn’t handle the volume… even the aid stations that can be driven to couldn’t handle it. We were literally out of everything by 3 p.m.,” Gary recalled about the 2013 edition. The aid station’s cutoff for inbound runners is 4:15 p.m. although runners continue to drift their way back over the pass until sunset, Gary said. That year, 1,200 entrants were accepted and 943 runners started—but the race’s National Forest Service permit allows for 850 runners. Based on a 30-year average of no-show percentages, the race allowed a higher number of entrants, but they were caught off guard when a higher percentage than normal appeared, according to Trail Runner Magazine. In the following years, the race organization pared down the entrant list.

But one of the greatest challenges of all was when Vicky retired. “Vicky is an amazing individual. She ran the cook tent for 30 years. Last year was my first year without her. I was as nervous as a cat in a cage full of pit bulls. It was a big role to take over, plus coordinating everything else that I do. It’s not the same without her,” Gary said.

The two are still good friends. Last summer, Vicky ventured to Leadville the week before the race for restful camping and catching up with the community. She also helped Gary double check the gear beforehand. Their farms are two hours apart, so the race is a reunion for them.

“Gary was in a little bit of a panic when I told him I was retiring. But the younger need to start taking over. He has wonderful volunteers, and he’s been doing it long enough that he knows what to do… He brings me fresh vegetables from his garden. We usually cook them on the campfire. Some things are hard to miss if you’re not there,” she said.

Vicky’s last year, she was utterly surprised by the gifts that the racers brought with them to Hope Pass.

“Thirty years is a long time to do something. Runners brought cards and one guy brought me a bottle of Bulleit bourbon. Carrying even an extra ounce up that hill is horrible,” said Vicky. “Runners really appreciate that we put in the extra effort to do the aid station. I don’t cry very easily, but I was in tears,” she said.

The aid station has become iconic and it’s a pivotal point in the race, Merilee explained: “Runners come out of the trees on the Twin Lakes side and there’s this pastoral meadow with dozens of llamas in it. Some are laying around, some are up eating, and it’s a beautiful view. At that point, the race goes from being a really physical, athletic event to being more mental. Over the years, that spot has been the impetus behind many runners’ successes for the support it provides.”

Ian Sharman, head coach of Sharman Ultra Endurance Coaching, has stood on the podium for the Leadville 100 Mile five times, including four wins. He says, “Hope Pass aid station is always a relief to see on the way out since that means the high point is so close and visible. Then, on the way back I always run straight through and just hammer the next 30 miles as hard as I can after completing the two main climbs of the race.”

Gary, now 57, has raised llamas since 1994. “I like doing pack trips in the backcountry. I thought, There’s got to be a better way than carrying all of this weight on my back,” he said. As if Gary doesn’t have enough jobs, he also has a llama-rental side business called Comanche Creek Llamas. (If you’re interested in renting, call Gary direct at 303-503-1234.)

When he’s not volunteering, Gary works a full-time job at King Soopers, where he’s worked for 32 years, in Commerce City. His second full-time job is running a 700-acre cattle ranch in Strasburg. When he’s off the clock, he takes pack trips with his llamas and friends, including hunting expeditions. For this year’s elk season, he’ll spend 11 days in the wilderness with a dozen llamas, a hunting comrade, and a 10-by-12-foot canvas-wall tent with cots and coolers. Of course, the llamas help carry out the catch. Gary doesn’t run, “In 1999, 2000, and 2001 I ran the 5k llama race in Fairplay. Other than that, I’m not a runner,” he said.

Vicky’s old llama, Stretch, has since passed. His daughter, Daisy, stands among Foster’s herd of six llamas on her nine-acre farm in Allenspark. Vicky works part-time at a wedding event center near her home. She still sends five llamas to Hope Pass each year, which her wrangler takes to Leadville for her. She also leases out her llamas via her business, Lightning Ridge Llamas.

Gary plans to continue volunteering on Hope Pass until, well, he simply can’t. “When I can’t physically do the tasks any more, I plan to stop. These days, with nerve problems and back problems the future is limited,” said Gary, who is most inspired by the synergy that occurs between the people who convene on Hope Pass.

“Hope Pass is history in the making. As llama packers, it’s this type of logistical trip that motivates us to do what we do. We train for years to learn how to haul weird and differently sized gear in the backcountry. Runners train their entire lives to run these races. And we all meet on Hope Pass. It’s like our dreams all meet up there.”

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you run the Leadville 100 Mile? If so, can you share what your experience at the Hope Pass aid station was like?

- Do you know Vicky Foster and Gary Carlton from the Hope Pass aid station or elsewhere? Can you share a story about them?

- And how about those llamas? Got a good Hope Pass llama story?