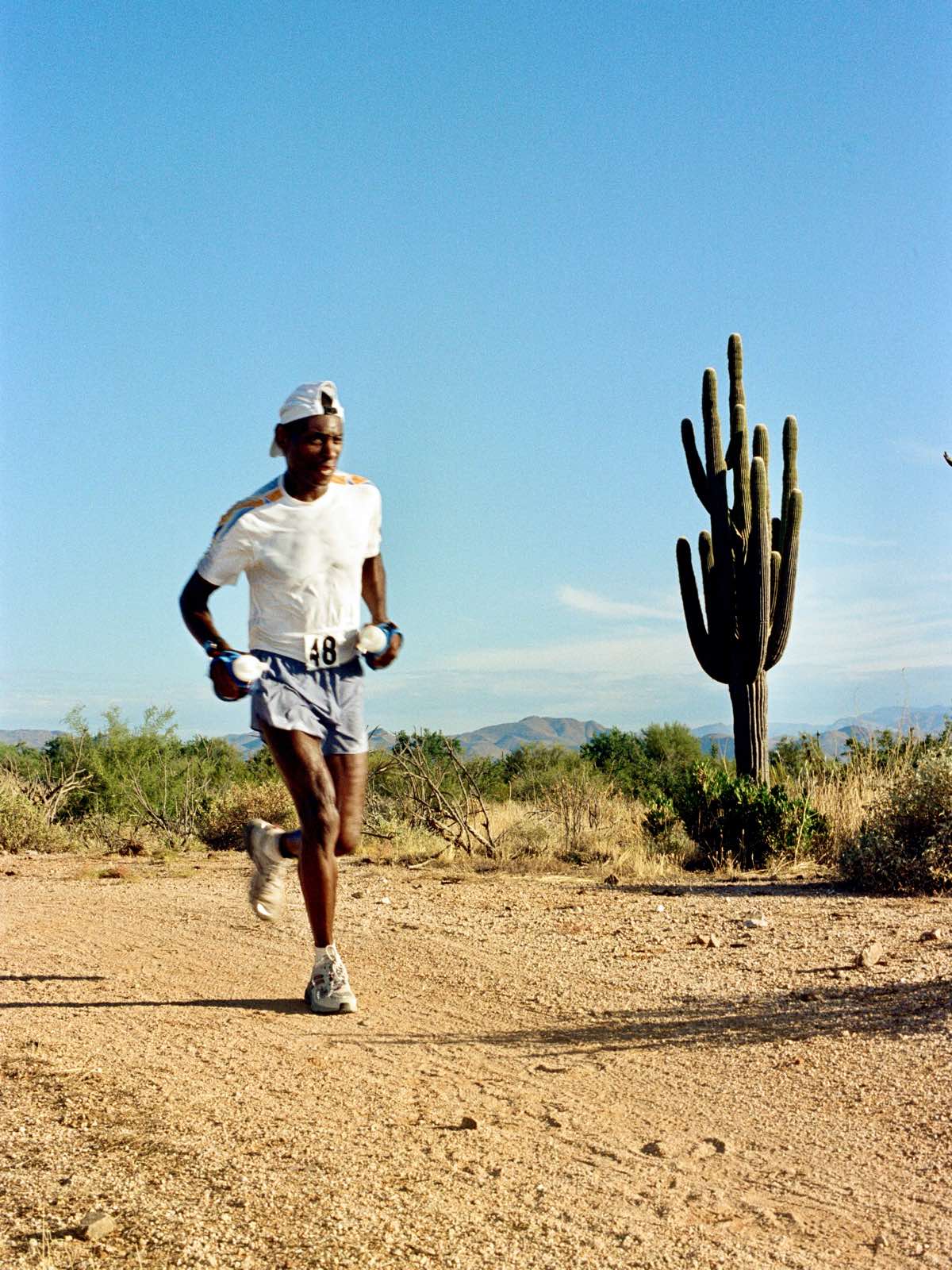

Ultrarunner, race director, writer, and volunteer Errol “Rocket” Jones has lived in Oakland, California, for the past five decades, where he runs daily. “He likes to run hard from the start, and that’s how he got his nickname, ‘The Rocket,’” says Jones’s close, long-time friend John Medinger. Barry Norback, nicknamed “No Miles Norback” by Jones, was the person first responsible for saddling Jones with the name “Rocket.” “Legendary ultrarunner Ann Trason perpetuated the name, saying, ‘That’s Errol, doing his rocket imitation. I hope he doesn’t flame out.’ It stuck. When he ran smart and under control, I couldn’t touch him,” says Medinger.

To date, the 71-year-old has participated in at least 171 races, since he first raced the 1982 American River 50 Mile, at age 32. Over the past 37 years, he’s experienced many of the most iconic 100 milers including the Badwater 135, Wasatch Front 100 Mile, Leadville Trail 100 Mile, Vermont 100 Mile, Bear 100 Mile, and even the Grand Slam of Ultrarunning series. Beyond the countless mileage he’s tracked, Jones’s entry into the community and sport reflects his resilience and determination.

Jones was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois, where he grew up with six younger siblings in the 1950s and ’60s. His parents separated at age eight. At the time, he wasn’t conscious of their circumstances, but reflects that it wasn’t always easy. “I’m from the housing projects initially, which is called Ida B. Wells. We had a very rough beginning, my family and I. We were materially impoverished,” he says. Jones wasn’t involved in high-school athletics. “I didn’t do organized sports. I didn’t do track and field. I was a kid on the streets. I just didn’t have an interest in it. I played kickball and that kind of thing, because that’s what we did as kids,” he says. Jones graduated from Hyde Park Academy High School and as an adult, moved to the north side of Chicago. In 1968, he enlisted in the military. He served in Vietnam, which was a “very unpleasant” experience, says Jones. After being discharged, he landed in California, where he spent six months before moving back to Chicago, in 1970.

The following year, he made a paramount life change when he became vegan. He’d smoked from age 13 to 21. He drank alcohol and he says his diet then was atrocious. He suffered from chest congestion. “I couldn’t hold a conversation for more than six minutes without me having to expel phlegm. I may have been lactose intolerant as well. I used to go to a physician for decongestants. I was an omnivore and a good friend of mine introduced me to veganism. And my friend, Jim Witherspoon, who was a vegetarian, made a bet with me that if I stopped eating meat and dairy food I wouldn’t have to go to doctor for decongestants. So I took him up on the bet—to shut this guy up and not with intention of changing my lifestyle,” says Jones. Less than two weeks later, his congestion dissipated, which led to a domino effect of other healthier choices.

During a transitional four years, Jones found an abundance of vitality. “I needed a place to channel that energy. My family and friends weren’t that accepting of the dietary transition and I needed to transfer that energy someplace,” he says. During that period, Jones started cycling long distances. He’d ride his 10-speed bike from the north to the south periphery of the city and even as far as Detroit, Michigan. But the U.S. Midwest winters were long, and he was eager to relocate where he could both cement the lifestyle changes he desired and extend his warm-weather season.

Ultimately, Jones’s lifestyle shift catapulted him to California, in 1976, where he found trail running and ultrarunning. “Everyone already knew me in Chicago—my family and friends weren’t that accepting of the dietary transition. I wanted to go somewhere where I could reinvent myself and be accepted.” He moved to California without a job but felt strongly that he would meet like-minded, healthy individuals. During his job hunt in San Francisco’s East Bay, Jones took breaks at Lake Merritt and saw people jogging around the water. He thought that running could be a good way to pass the time. He enjoyed a 3.1-mile run around the lake one day, and it became a daily practice. He added distance to make two- and then three-lap jaunts. He enrolled at Laney College, and made friends in San Francisco, who he ran with along Golden Gate Park. When he watched Frank Shorter race the Montreal Marathon on television, it changed his entire idea of running. He decided to take on a marathon.

Jones signed up for the 1977 Mayor Daley Marathon in Chicago. He participated in the race while visiting his sister. “I blew up, but I finished it in 3 hours and 48 minutes. That was my first foray into marathons,” he says. Without pause, he signed up for California’a Livermore Valley Marathon. After four years of running marathons—and chipping away his time to about 2:30—he discovered ultrarunning, when he was working as a property manager in Berkeley. Jones had an office space in a sports-care center and saw a picture on the office wall of Nick Daley in running shorts and a singlet on top of a white-capped peak. Daley was the director of the sports-care center and an ultramarathoner. The photo was taken during the Western States 100. “I didn’t know anything existed beyond a marathon distance, and I didn’t know about terrain beyond the road. Nick suggested I go on a trail run with him,” says Jones.

Until that point, Jones had run in town parks and on “manicured and tame” trails. But with Daley, “The trails we ran were out in what felt like the midst of wilderness relative to running city streets. It was in the Berkeley Hills above Oakland. I loved it from the moment we started to run right up until we got to his home,” remembers Jones. Their run was more than 20 miles and four hours on trail. Without that “watershed moment,” with Daley’s input, Jones may never have known of the sport.

Jones’s first ultramarathon was the 1982 American River 50 Mile in Sacramento. There were 300 to 400 people at the race, Jones recalls, and he finished in 8 hours and 28 minutes. “I took off in that event as if it were a road marathon. I ran the first 25 miles in about 2 hours and 40 minutes. Then, I took almost five hours to do that other half. I ran in the mindset of a road runner, so I wasn’t eating food. I wasn’t drinking water. I paid the price for it. I sat in the dirt and cramped up. I learned about what you need to prepare and during the course of that run,” says Jones. Over the years, Jones adapted and began to excel. For example, in the 1991 California 50 Mile, he crossed the finish in 10th overall with a time of 7:41, at age 41.

“Errol was always a better runner than me—but only by a little bit. There’s a lot of good-natured banter between us,” says Medinger. “Our racing tactics are entirely different. He likes to run hard from the start…. When he ran smart and under control, I couldn’t touch him. But he was usually aggressive, often recklessly so. I’d always joke that the further ahead of me he was halfway through a race, the better chance I had to catch him. I’d only beat him in a race maybe once every half dozen times, but it was just often enough to keep him honest.”

A decade after he moved west, Jones met his trail running buddy Medinger, in 1987. “I had recently moved to Oakland and was doing a long run in parkland between Oakland and the city of Danville, to the east. On a middle-of-nowhere trail—more than five miles from the nearest trailhead—I was heading back, and Errol was running outbound. We stopped, and I said, ‘It seems like I should know you,’” recalls Medinger. “We chatted for a few minutes. He decided to run back with me. We exchanged phone numbers—this was before the internet and social media. He called a few days later, and we ran long together again the following Saturday. The rest is history. We ran long together almost every weekend for the next 20 years, and often once or twice during the week. At one point, we calculated that we’ve run more than 30,000 miles together. We’ve crewed and paced each other at races many times.”

The Rocket and “Tropical John” Medinger at the 1995 Western States 100. Photo courtesy of John Medinger.

When the two became friends, it was four years after Medinger founded the Quad Dipsea race. The route was composed of four crossings of the famous seven-mile Dipsea Trail in Mill Valley, where Medinger lived at the time. Jones became the co-race director of the Quad Dipsea, a role he continues even after Medinger handed over his position to John Catts, in 2013. “I started Quad Dipsea first as a group fun run, and then a couple of years later, as an actual race. Obviously you need help, and the first people you look to are your friends. Errol was stuck with it, but he totally embraced it. First and foremost, he’s an exceptionally hard worker. He’s willing to do any and every task—it doesn’t matter how much grunt work it is. He’s friendly and cheerful throughout. After years and years of practice, he’s gotten really skilled at truck loading, clean up, and putting things away in their proper place. Sounds simple, but it’s not. I try to get plenty of help for him, but he’s very picky about who he works with. You gotta’ be able to keep up, willing to work hard, and do whatever it takes,” says Medinger.

Jones’s philanthropy and generosity continued to flourish. “Like everyone in the sport, I wanted to give back,” he says. Jones became a long-standing volunteer at Lake Sonoma 50 Mile and Miwok 100k, both in California. From 2001 to 2017, he also co-race directed the Bear 100 Mile in Utah and Idaho alongside Leland Barker. Jones first got involved with the Bear following a friendly bet. It was 1999. He’d DNFed the Wasatch Front 100 Mile, in early September, but Medinger and Jones had a pact to finish at least one 100-mile race each year. Medinger had heard about a new 100 miler that was supposed to take place in two weeks: the Bear. Jones called Barker to ask if a spot was still open and registered for the race. Jones finished fourth overall in 29:43, at age 49. He returned the following year as both a participant and volunteer.

Whether he was volunteering at Lake Sonoma, Miwok, or the Bear, “I was a fixture, a co-RD, in effect. These race directors are my best friends, so when they put on an event, it doesn’t matter, I’m there,” says Jones. “I organized the aid stations. I always drive the trucks. I can’t think of anything I don’t do…. There is nothing that I don’t love about this sport. Including the pain.”

In 1987, he entered his first 100 miler at the Western States 100, which is still one of his favorite races to date. He was pulled for medical reasons and did not finish. Four years later, he officially finished the race, in 1991. “Western States is the granddaddy of the sport. That was my first 100 miler. Badwater and the Bear are also big favorites of mine. I can’t think of an event that I’ve run that I haven’t really enjoyed no matter how tortuous is seemed at the time. I like the idea of strapping on a pair of shoes and getting out in the wild and having at it,” he says.

Until a few years ago and for six years, Jones was also a monthly contributor to UltraRunning Magazine, via the “Rocket Rants” column. Medinger, a former publisher of the magazine, says the column was so popular because, “His voice is 100% genuine. And he’s got standing. He’s the cagey veteran who has been running ultras for nearly 40 years. He’s the very definition of old school. He likes things a certain way and is unhesitating when it comes to calling out anyone who does things in a way he doesn’t like. He’s run the Grand Slam, Badwater several times, a bunch of stuff. He’s done more volunteer work than just about anybody this side of Stan Jensen. In person on the trail, he’s loud and gregarious. He’s got a smile and an encouraging word for everybody. He’s often the only Black runner out there, so he’s pretty hard to miss. His encouragement is contagious; people naturally gravitate to him. All of that comes through in his writing—you see the words on the page, and you can hear them coming straight out of his mouth,” says Medinger.

Outside of the sport, Jones managed property for about seven years. Then he worked at the Children’s Home Society in San Francisco to assist abused children. He supplemented his income by doing remodeling work, which ultimately became his career path until he retired at age 65. He’s been married, divorced, and is single now.

The sport of trail running and ultrarunning has evolved over the decades to now offer countless options across distances, the United States, and world. As with most evolutions, there are pros and cons. “I do miss the intimacy. I miss going to events where everyone knew one another. I’ve noticed the increase of runners. But with everything, there’s change. I just go with the flow. And I do like the idea that we have so many more events to choose from,” he says.

From the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s to the current protests for equality and equity for African Americans, Jones recognizes that positive growth has occurred in the United States, yet more is needed ahead. “We have without question made progress in this country, as far as race relations are concerned. Obviously, there’s a lot more that needs to be done. I’m really happy to see the movement that’s in place now. As a Black man in America, I know what it’s like to feel oppressed,” he says.

As an African American, Jones’s perspective is that the marathon and ultrarunning communities have both been “very accepting” spaces for people of color over the decades. “Sports and race relations seem to me very separate things. What I love about running is that politics and religion never seem to enter. As we talk about inequalities, oppression, and acceptance, I’ve never felt inequality in ultrarunning,” he explains.

Ultimately, an attraction to these sports boils down to the individual and perhaps, cultural and familial influences. Jones says, “There have been no [communal] barriers to African Americans participating in marathons and ultramarathons. Though, from the beginning, Blacks have been a novelty in ultrarunning. We’re still a microcosm when you consider the African American population. I don’t think there’s much the white community can do to incorporate more Black people into the sport. If it doesn’t speak to their heart, it’s not a path they’ll venture down.”

However, the fiscal cost of race involvement can be prohibitive, and the income that can be accrued by professional athletes—which is an incentive to African American and Black runners—is more economic in marathon running compared to ultrarunning, Jones says. “There are systemic barriers in America for housing, education, and jobs for Blacks. There have been many more African American marathoners compared to ultrarunning, because there has been money to be had in road racing. That might be one reason that ultrarunning as a sport hasn’t appealed to African Americans, because it’s an expensive endeavor and no matter how well you fare in the sport there’s no payday to be had. That’s a very frivolous, unappealing expense to the average African American runner—the idea of spending $400 to $500 for an entry fee to run a 100 miler to get a belt buckle. They don’t have the material wherewithal not to mention the hydration packs and nutrition food. You’re not going to run a 100 miler and spend less than $1,000 in preparation for that sport. There’s the entry fee, airfare, car rental, and hotel accommodation for the event itself. There are months of training that lead up to that event, so endless pairs of shoes and going places to train. It can be very costly.”

Across the decades, Jones and Medinger have become family. “He’s the brother I never had. It’s odd, because we came from completely different backgrounds,” says Medinger. “I’m white and grew up in lily-white middle-class Oregon. He’s black and grew up poor in the projects in Chicago. I worked as an executive at a big corporation. He worked first as a social worker and later as a building contractor. But whatever the subject—virtually anything and everything—we see the world the same way. We have the same reaction to people, politics, and world events.”

Jones is now a 12-hour drive away from Medinger and his family, who moved to Arizona a year ago. The two don’t see each other as often as they’d like to but talk on the phone a couple of times a week. “When we do get together, we pick up right where we left off. And we typically holiday together once or twice a year,” says Medinger.

Running remains Jones’s motivation and fuel. “For me, running is my life blood. Since I started running marathons, I’ve really loved it. Every day is a running day for me. It doesn’t really matter what the distance is. I need to get out there. For myriad reasons, I sometimes can’t run as much as I like because of work or injury, but I always try to find a way to get out there. Also, if I’m pointed toward a particular event, there are certain hallmarks in my runs like track, hill, and heat workouts that I like to hit. But basically, if I’m running then I find happiness. As long as I’m hitting the bricks every day, I’m thrilled,” Jones says.

This month, Jones will run the Heartland 100 Mile on rural gravel roads in Kansas. His most recent 100 miler was the 2012 Bear, meaning that this event will be his first 100-mile race in his seventies. Jones recognizes that this may be his last 100 miler—wish him luck, good health, and rocket feet! He says, “I need a 100-mile finish. I love this stuff, and I love the act of running 100 miles. I like all the highs and lows of it. I really look forward to getting this out of the way!”

Above all, Rocket says, “As I continue my exit from the ultrarunning scene, I’d like to be remembered as the guy who loved the sport and did his best to enjoy every moment and to give back to the sport that he loved.”

Call for Comments

Leave your stories about running, racing, and volunteering with Errol “Rocket” Jones in the comments! Thank you.