You might have heard of Flyathlon, an annual trail running series organized by the nonprofit Running Rivers that combines fly fishing, camaraderie, fundraising, and microbrews. Based in Colorado and Iowa, Flyathlon race routes follow a waterway where participants stop at any point in the run to fish. At the race’s end, they submit a photo of their catch for an opportunity to win an award like Biggest and Smallest Fish.

Even if you know Flyathon, you might not have heard why Running Rivers founder Andrew Todd launched this unique race series, whose motto of “run, fish, beer” is a riff on the traditional triathlon. In the eight years since it started, the venture has fundraised close to $250,000 for native trout conservation projects. Todd—a family man and runner seeking to make outdoor recreation less intimidating and more inclusive—voluntarily used his expertise in biology and environmental engineering to preserve the wild natural resources from which we thrive and survive as runners and people. Through fun events, his hope is to get more folks engaged in that preservation process, too.

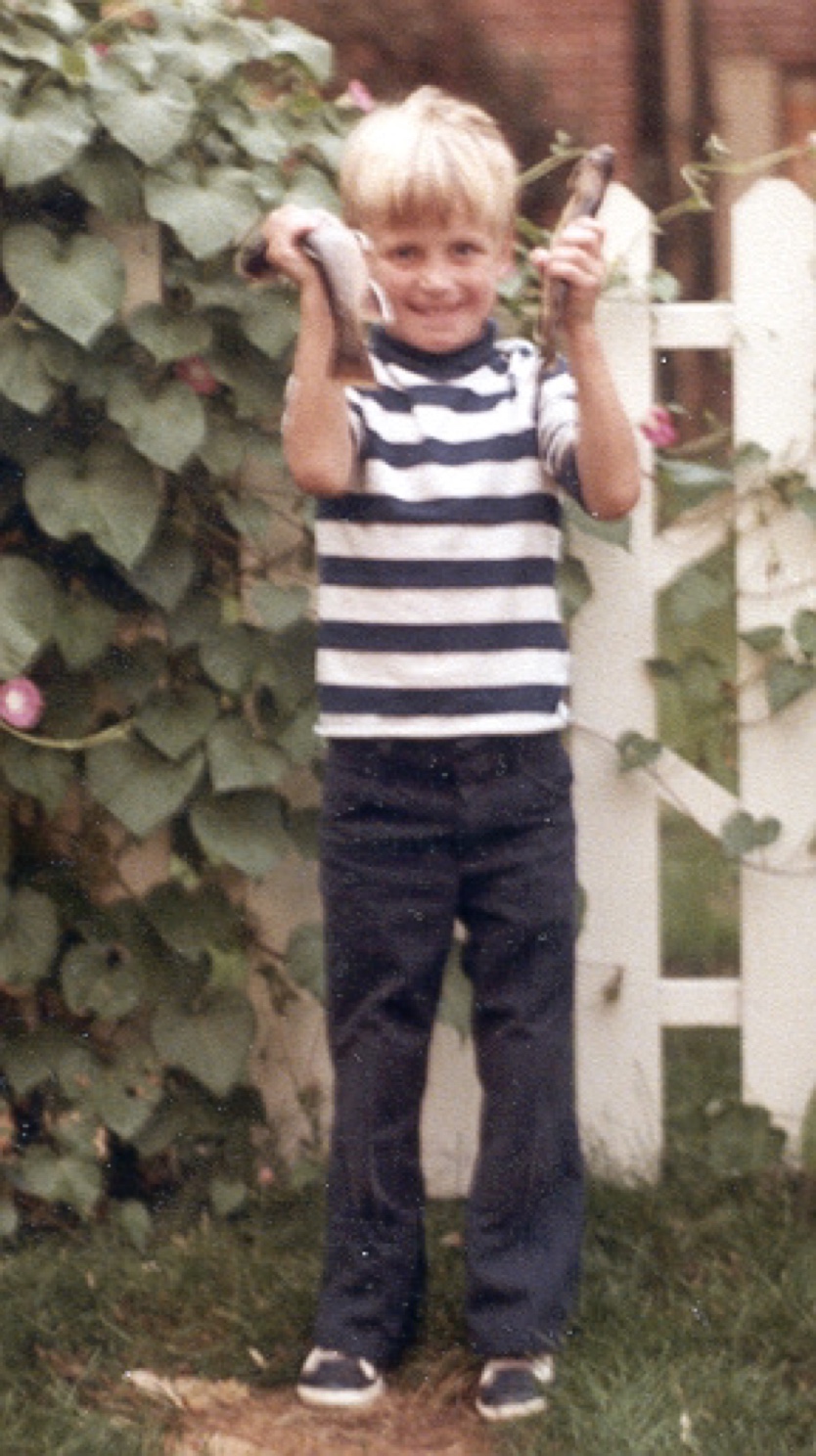

Andrew Todd after landing a monster cutthroat trout at an undisclosed location way back in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of Colorado. All photos courtesy of Andrew Todd unless otherwise noted.

Todd grew up in Denver, the now-bustling capital of Colorado, with two older brothers and a younger sister: Mike, Jim, and Kristin. He’s the avid angler among his siblings, who were first introduced to a fly rod on an annual trip they took with their dad to Aspen, Colorado. Their dad, Jim, was a pediatrician and infectious-disease specialist, and would attend a conference in the Elk Mountains, so they’d relax by tossing a line on a creek after business was wrapped up. Growing up, Todd played lacrosse—which he pursued while earning his undergraduate degree at Williams College in Massachusetts—and also twice enrolled in a formative outdoor leadership program. During the program, the group completed a seven-day backpacking trip in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the southernmost subrange of the Rocky Mountains and a large cluster of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, 240 miles south of Denver. During that hike, they summited Humbolt Peak and Crestone Needle, which are ingrained in Todd’s memory. A rugged road along a route he hiked during those two back-to-back summers is now nearby to a cabin that he bought later in life, with his wife Cassie. Over the years, his connection to that mountain range has influenced his scientific research, conservation work, and the earliest Flyathlon locations.

After finishing his undergraduate studies, Todd moved back to Colorado, where he worked on his masters degree and PhD in environmental engineering at the University of Colorado Boulder. “I wanted to study engineering and the environment to work on rivers and streams and do restoration. It turns out, that field is a more a focus on wastewater treatment. But I had a really awesome advisor at UC Boulder who allowed me to make the degree what I wanted it to be, which was to focus on engineering in the environment, so that I could study how rivers formed and stream ecology—which was my favorite course in graduate school—and put me on the path I’m on now,” says Todd. At a mutual friend’s party, Todd reconnected with Cassie, who he’d gone to high school with but hadn’t seen in years. She was going to veterinary school at Colorado State University, 65 miles north of Boulder. Around that time, Todd also got involved in his first formal run event, which his brothers roped him into.

“In college, lacrosse consumed my physical fitness. After college, I no longer had an organized sport and needed to find a way to stay in shape—I was not. My brothers challenged me, because they were older and out of college and had started road running, to run the St. George Marathon, in Utah, with them. It crushed me. I decided I liked the zen of long-distance running even though I was terrible at it. I did a couple more road marathons,” says Todd. After completing his degrees, Todd’s first workforce job was as a research biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey. He hiked through remote wilderness all over Colorado and the U.S. West and realized there were countless places he’d like to go fish. Around 2001, an idea was born. After his fieldwork, he’d trail run to those gorgeous bodies of water, fly rod in hand to catch fish, and run back to his basecamp, where a cooler full of food and beer was ready. One such destination where his research took him later became a present-day route for the Flyathlon events.

“I was researching cutthroat trout around the Rio Grande. That fish is native to Colorado’s San Luis Valley and northern New Mexico. As the climate has warmed, these remote watershed flows have become less reliable, there are more extreme flow events, and some of these creeks where these fish are might be not dependable in the future. I saw that there are opportunities for better watersheds for the long-term survival and a different climate future for these fish,” explains Todd.

Three years after debuting the first official Flyathlon event, in collaboration with Colorado Trout Unlimited, Todd decided to launch a Colorado-based nonprofit that could funnel the event profits directly into native trout conservation projects. The year was 2016 and Running Rivers was born. One of their inaugural efforts was to donate $25,000 to the first phase of the 2020 Sand Creek watershed reclamation project, located in Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, adjacent to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The Sand Creek watershed is a strong, sustainable location for the preservation of the native Rio Grande cutthroat trout, thanks to three large headwater lakes and more than 15 miles of frigid perennial river habitat.

Today, Running Rivers has supported an array of conservation projects from trail restoration along the East Middle Creek in the Rio Grande National Forest to educational signage about a recent Colorado River cutthroat trout discovery near Steamboat Springs. To raise additional funds and educate folks in a creative way, they launched another ongoing collaboration with local microbreweries dubbed the Rare Fish / Rare Beer Project. The organization partners with conservation-centric brewers to develop limited-edition craft beers with names and labels that celebrate a native fish within a backyard watershed. To date, they’ve released seven beers including the Trucha Grande, a collaboration with Three Barrel Brewing Company, Laws Whiskey House, and the Colorado Malting Company. Trucha Grande celebrates the Rio Grande cutthroat trout.

Four years ago, Todd transitioned out of the U.S. Geological Survey to take a new role with the Environmental Protection Agency. At first, his responsibilities included technical support and risk assessment for superfund sites in this U.S. region—in other words, helping the most polluted water sites in the country.

“My job was to characterize the risk of those sites to the ecological environment. The Bonita Peak Mining District was my primary focus, which was the headwaters of the Animas River, and I came on after the 2015 Gold King Mine spill,” explains Todd. The Gold King Mine is located near Silverton, Colorado, and the Hardrock 100 course. Within 24 hours of the spill, the Animas River between Silverton and Durango turned completely yellow, due to the oxidation of dissolved iron, which was released in the waste water. “The work is ongoing and will be for years. There are a ton of legacy mines up there. When you have hundreds of mines, where do you focus? You can’t work on them all nor would it make sense to, because some are higher risk and contributing more contaminants. The process now is to evaluate the highest risk sites and prioritize how to address those. Some of these mines are in places where guys seemed like they were dared to go—the remediation challenges are significant. Abandoned mines are one of the biggest water-quality issues of the American West.”

Furthermore, decaying and collapsing metal pipes and tunnels are highly toxic to organisms in creeks including trout, which are sensitive, as are the insects that the trout feast on. Last year, Todd was promoted to a management role, so he oversees the group that works with the states and tribes in this region to ensure they comply with water quality regulations for human health and the aquatic environment. His six-state region includes Colorado, Wyoming, North and South Dakota, Utah, and Montana.

Though the Flyathlon events started and continue in Colorado, an event has since been brought to Iowa and Todd hopes other locations will seek to become host destinations, too. Todd says, “Someone Iowa reached out to start their own and has been running it for five years. They’ve turned it into what they want it to be. We asked they maintain the core principles with fundraising and supporting fly fishing and native trout conservation. If and when these Flyathlon events expand more, it’ll be because someone is equally passionate about those things and wants to make it their own for the benefit of their local resources.”

The coveted Troutman belt buckle, handmade by metal sculptor and fly fishing badass, Amanda Willshire. Photo: Amanda Willshire

The nonprofit has an 11-member board and everyone, including Todd, volunteers for the organization’s mission. With the help of sponsors, the organization offers prizes to incentivize registrants to fundraise $250 minimum per race. The top fundraisers are rewarded with gifts like a YETI cooler or Scarpa gear. As an increasing sum has been raised, the board is working on developing a formal application process for the conservation funds.

Todd explains, “I’m in the industry and couple of our board members are as well, so we hear about a lot of conservation projects through our research, personal connections, and word of mouth. Sometimes someone tells us, ‘We’re $5,000 short of building a barrier.’ A big part of the conservation of these fish is isolating them from non-native fish, so a large cost of native trout is building barriers to prevent non-native fish from coming into a habitat. We can provide that fund fast. If it’s a project like on the Sand Creek watershed, I knew about it and was involved in developing the science around this watershed, so when it came time to pay $18,000 for a helicopter, Colorado Parks and Wildlife could approach us. We don’t want it to be perceived as you can’t be funded unless you know these three people, but this also allows us to be nimble versus a drawn-out process of going through applications and an issue of us not having the bandwidth to process those applications. We want this process to be transparent to the people who are asking their friends and family to contribute.”

In addition to Flyathon, Running Rivers facilitates several personal challenges, and one of those is Troutman. Troutman is a unique challenge requiring one to catch the grand slam of trout—meaning one each of a brook, brown, cutthroat, and rainbow trout–run at least a marathon, climb at least 3,000 feet, and drink a beer of at least 12% ABV all within 12 hours.

Most recently, during the pandemic, Running Rivers launched a virtual challenge, the 2020 Socially Distanced Flyathlon Challenge. More than 100 athletes nationwide ran and fished in their backyards and home streams and raised more than $25,000 for native trout projects. The virtual event was such a success that it will be ongoing as the Long Distance Release Flyathlon. In the past, Running Rivers has also hosted events for kiddos like the Kids Flyathlon in Staunton State Park, where 75 young runners ran a loop by the ponds and drank root-beer floats at the finish line.

Mayhem at the starting line of the 2019 Kids Flyathlon, held at Staunton State Park in Colorado. Photo: Craig Hoffman

As for Todd’s goals, he finished an unsupported 50 miler through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains last year. In August, he’s planning on racing the Staunton Rocks! Marathon & Half Marathon. He’ll also go for the Ültroüt challenge. Recently conceptualized by Todd and iRunFar’s Editor-in-Chief Bryon Powell, who serves on the Running Rivers board, the Ültroüt challenge asks participants to run at least 50 miles with an elevation gain of more than 5,555 feet, catch five fish species (four must be trout), and drink a craft beer of 15% ABV within 18 hours. No one’s yet started—or completed—this adventure.

When he’s not racing, he’ll be spending time with Cassie, his parents, kids Kate and Lane, and three Terriers Eddie Vedder, Pearl, and Bee Girl. And of course, he’s planning on giving back to our environment through conservation efforts, all while facilitating memorable events that rope others onto the conservation bandwagon, too.

A Colorado boy and his girls (wife Cassie and daughters Lane and Kate) on an adventure on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Regardless of whether a trail runner chooses to volunteer at a regional race event, does trail work with a local conservation organization, or lends a hand at an established state or national park, we all have an opportunity to give back to the wild spaces we use, cherish, and want to preserve for years and generations to come.

As Todd says, “By pairing these two activities, trail running and fly fishing, I hope people see that we’re in these incredible places when we’re running. I hope that they can take their time and recognize that there’s more to that environment than just the trail—I want people to be more aware. Now, a new pressure is being created from more people realizing that the outdoors exists. If we have all these people getting interested in these wild places, I hope there are opportunities for runners to be more conscious and to give back and invest in it—it won’t be as awesome if we’re all using and not giving back.”

Call for Comments

Calling all stories about Andrew Todd. Leave a comment to share your story about running, fly fishing, or drinking a bit of beer with him!