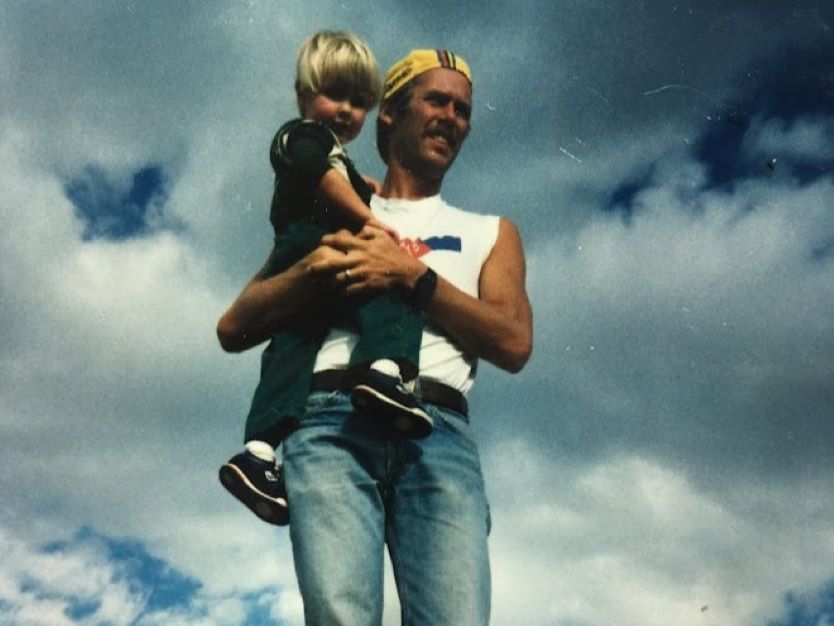

One of endurance athlete Travis Macy’s most formidable race memories is from childhood. In the cloak of predawn, the five-year-old in leopard tights and a mountain lion T-shirt stood with a crowd of ultrarunners on the corner of 6th Street and Harrison Avenue in Leadville, Colorado, waiting for his dad to start the now iconic Leadville 100 Mile.

His father is Mark “Mace” Macy, a pioneer ultrarunner in the mid-1980s — when the term “ultrarunning” was born — and a legendary adventure racer from the early 1990s onward. Mace has raced on Team Stray Dogs around the world, including in British Columbia, Argentina, and Morocco, while each event aired on the reality TV show “Eco-Challenge.”

In total, he competed in eight Eco-Challenge races from 1995 to 2019. Mark and his wife, Pam, raised their kids — Travis and his two sisters — in a home full of adventurous spirit and positive mantras, in Evergreen, Colorado.

Leadville 100 Mile race director Ken Chlouber fired the shot, signaling for racers to go. The year was 1988.

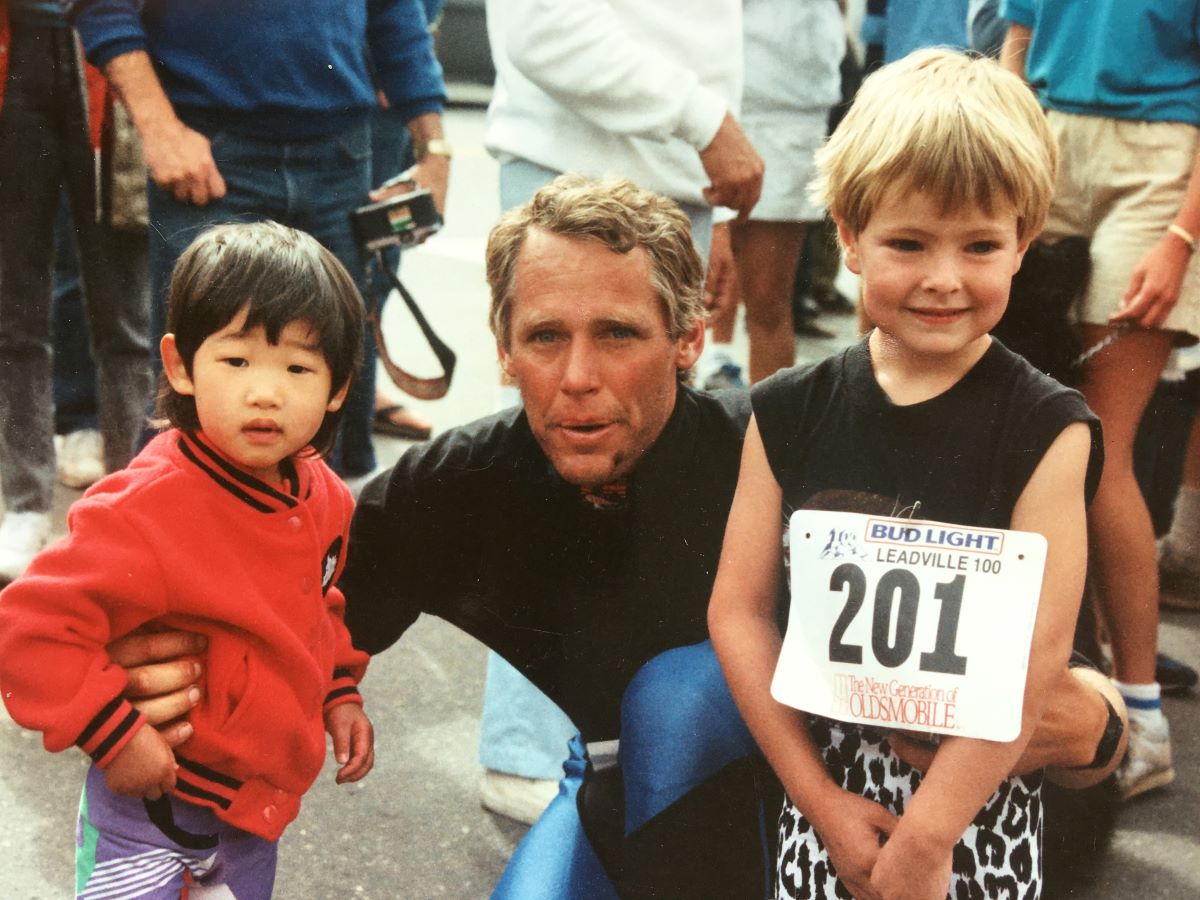

The young Travis Macy (right) at the 1988 Leadville 100 Mile with his father Mark Macy (center). All photos courtesy of Travis Macy.

Twenty-five years later, Travis stood at the Leadville 100 Mile start line on August 18, 2013. By the end of his first century-distance run, he secured 15th place, leaning on his dad’s axioms, including “don’t quit.” He also won and set a record for what’s called the Lead Challenge, completing the entire Leadville Race Series in a single summer with a cumulative record time. The challenge includes finishing the Leadville Trail Marathon, either the Silver Rush 50 Mile Mountain Bike or the Silver Rush 50 Mile Run, the Leadville 100 Mile Mountain Bike, the Leadville 10k, and the Leadville 100 Mile.

For the next few years, Travis joined Hoka as an ultrarunning athlete, finishing endurance races such as the HURT 100 Mile, Wasatch Front 100 Mile, and San Juan Solstice 50 Mile. His career took flight as a motivational speaker, coach, and athlete. He published the book, “The Ultra Mindset: An Endurance Champion’s 8 Core Principles for Success in Business, Sports, and Life,” and would go on to race 130 ultra-distance events across 17 countries.

Not visible at the time, this high period of hard work, joy, and reward would become a peak for Travis and his family — followed by a challenging storm.

By 2015, Mark, who was a trial attorney, would occasionally lose his train of thought during depositions in court. He decided to retire. He also got brain imaging, which came back normal. Mark and Pam — high school sweethearts who grew up in Livonia, Michigan, but had made a life in Colorado — bought a travel trailer to take a long road trip. While they were traveling, Pam remembers a startling moment when Mark, a superb navigator, could not read a map.

There were other signs that he’d changed, too. Out of a complex mix of respect for Mark coming to the realization himself, a belief in positivity, and a fear of the diagnosis, the Macy family didn’t yet seek medical insight.

Mark Macy (right) with fellow ultrarunners, adventure racers on Team Stray Dogs, and friends Marshall Ulrich (center) and Dr. Bob Haugh (left).

They also soon became distracted by another medical emergency. Pam needed another kidney replacement — she’d previously had two. As the family worked to find a transplant donor, her younger brother, Eric, ended up being a match, which revived her.

In 2017 and 2018, Pam approached Travis and his sisters to ask if they’d noticed any changes in their dad’s mental state. Mark now seemed more withdrawn at social events, inconsistent with driving and directions, and had trouble finding words and remembering names.

In the perspective of Travis, now 39, his dad put off neurological testing for a couple of personal reasons. Namely, he’d wanted to donate a kidney, to pay forward “the selfless donors who had come to Mom’s rescue three times in the past,” writes Travis in his and Mark’s new book, “A Mile at a Time: A Father and Son’s Inspiring Alzheimer’s Journey of Love, Adventure and Hope.” Coauthored with Patrick Regan, the book will launch on March 14, 2023, and is available for preorder now.

Travis has since learned how important a punctual diagnosis can be. He writes, “Early identification greatly expands treatment options and potential for mild cognitive impairment from Alzheimer’s [disease], and other dementias. If you think you or someone you care about might benefit from testing, please initiate the tough conversations and take action now. Not later.”

At 64 years old, Mark was officially diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease on October 16, 2018, confirmed through visits to several different doctors and the completion of various exams. Given the signs, Travis was not surprised yet was in complete shock.

The immediate cycle of grief sent Travis spinning with anger, helplessness, pride, and love, he recalls. It was impossible to not feel anxiety and worry about what the future held for his dad. How would they stay connected as father and son, mentor and mentee, and as teammates? Needing to care-give for his dad was happening far sooner than he’d imagined it would, and he didn’t feel ready to step into this new role.

As he tried to make sense of the change, he grappled with justification. Why would such a crisis happen to a person who is generous, hard-working, and gives back positively to the world? While peace and acceptance on some level were needed to move forward, this harsh new reality didn’t feel fair, even with a lens full of positive life mantras.

According to a journal entry, Mark writes, “When I tell people of my Alzheimer’s, they often ask, when did you know and how did you know it? Just like everybody else, I started having some word-finding problems, which as I understand it, those symptoms alone don’t necessarily mean you have Alzheimer’s, and in fact those symptoms can be normal.

“But in my case, I was a trial lawyer and had to talk to people every single day, and ultimately, I started to forget names and topics of conversation. I was aware I wasn’t the same, but no one else noticed. In fact, for many people, that may still be the case. I was well aware of the fact I had cognitive troubles as early as age 60, which was two years before I retired and even mentioned it to a partner, and the response was always, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’”

Mark agreed to give a talk on his journey and early onset Alzheimer’s at the Evergreen, Colorado’s recreation center, where he often trained, in November 2018. In a closing remark, he announced he’d be racing the Eco-Challenge in Fiji in 2019 — if they let him in. The seven-day, 400-mile adventure race includes trekking, biking, paddling, navigating, swimming, and canyoneering through jungle, swamps, mountains, rivers, and ocean, and would be deemed one of the most challenging races on the planet. Travis wanted to support his dad but wasn’t sure if “the world’s toughest race” would be possible.

“We had been at a lot of races together but had never raced together on the same team. We’d been on different teams and at the same adventure race. In 2008, we did a stage race called Rock and Ice Ultra in the Northwest Territories in Canada, where you run and snowshoe all day. I had spent a lot of time in Alaska, and it was nothing compared to Canada, in Yellowknife. It was a lot of 20 degrees Fahrenheit below,” explains Travis.

Travis felt torn. He wanted to help his dad live his best life and race. He also grappled with existential questions and coming to terms with his own mortality alongside his father’s. His mindset, perhaps inevitably, had shifted. A fixation on pushing through hard moments because things would work out opened to include other mental tactics: slowing down, asking for help, and looking for nonconventional solutions. To help manage anxiety and depression, Travis realized he needed to stop drinking alcohol, go to therapy, and use medication for management.

Despite Mark’s outward resilience and contagious optimism, he, too, struggled with this new reality. In a November 23, 2018, journal entry, Mark writes:

“In our family, probably like most, at Thanksgiving dinner we all sit around the table and recite what we are thankful for. Of course this year, like every year, I’m very thankful for my Pam and my kids and my grandkids and everybody in the family. Right now, however, as I sit in my office downstairs, I can’t think of anything I’m particularly thankful for this year. In fact, the only thing I can think of at this point in time is, ‘Why did I have to get Alzheimer’s disease?’ Of course, we’ve been through that before and there is no good answer. That is a bummer.”

Mark was raised to be a strong, independent athlete. He played sports all his life including football, baseball, basketball, and lacrosse, he recalls. Similarly, Travis grew up participating in team sports. In high school, he started running on track and cross country. His team won various league championships and he set several cross-country course records. Travis was also titled Athlete of the Year and Scholar Athlete of the Year as a senior. He pursued a collegiate running career at the University of Colorado Boulder, running 1,500-, 3,000-, and 5,000-meter distances. He finished fourth at the 2002 Jack Christensen Invitational in the 5,000 meters. By his junior year, he shifted to the club triathlon team.

“By my senior year, I’d done my first couple adventure races and I’d paced some people for 50 miles at Leadville. I realized I wanted to do the long stuff. I focused mostly on adventure racing and some ultrarunning mixed in,” says Travis.

He was most motivated by the internal lessons he gleaned from ultra races. “A sport like ultrarunning can make you a better person in the things that really matter in life and that starts with your family and how you support each other. It’s taught me patience. We try to plan ahead and do as many things as we can to be ready for the challenges that come, but really in an ultrarunning race, it’s about grappling with challenges and solving them along the way. That’s what we have to do on the Alzheimer’s journey,” he says.

Mark’s love for the outdoors was rooted in canoe and backpacking trips, which flourished into rock climbing and backcountry skiing in the 1980s when he and Pam moved to Colorado, where they still live today.

“I used to do a great deal of cross-country skiing. I was one of the early people doing backcountry skiing in the early 1980s with leather boots when people were feeling their way through it. I was climbing up on cross-country skis, up big hills and mountains. I haven’t gone for a while. I used to do a lot,” says Mark.

Then, when he watched triathlete Julie Moss cross the finish line of the 1982 Ironman competition, Mark, along with a new generation of triathletes, was inspired to pursue endurance races. He finished his first marathon in Denver, Colorado, followed by the 1986 Ironman World Championships in Hawaii. That was the start.

Eleven months after his diagnosis, Mark struggled to buckle his seatbelt on the jet flying over the Pacific Ocean from the U.S. to Fiji. Team Endure had been accepted into Eco-Challenge and was composed of iconic adventure racers Danelle “Nellie” Ballengee, Shane Sigle, Travis and Mark Macy, as well as team assistant crew member Andrew Speers.

Mark hoped they wouldn’t hit obstacles too great along the way. Sleep deprivation, for one, is not a good variable to mix with Alzheimer’s. They’d need to prioritize stopping each day to get a full night’s sleep.

Even so, there were moments when Mark woke up at night and wandered away — thankfully not too far — while the team slept. Other times, he completely forgot what they were doing altogether or where. Travis recalls the disorientation Mark experienced on the night before the race started, which helped Mark remember the episode.

“That wasn’t a good night. We had a really nice hotel room with a great, glass front [window] on it. After we were in there for a short period of time, I didn’t know where we were. And then I saw glass. I was like, ‘What is going on?’ It’s a little scary,” Mark says.

Other moments in the field held even more confusion. F-bombs were dropped. Microphones on cameras filming the event for the next reality TV series were covered. Tears were shed. It was not in any sense of the word “easy.” At the same time, with decades of experience in adventure racing and ultrarunning, Mark’s fitness, tenacity, pace, and endurance were incredibly high.

Ultimately, they participated in what would become one of the greatest adventures of their lives as father and son.

“Fiji was great. We had a great time. It’s a great place to be and there are great people who live in Fiji. It’s a great place to go if you ever get a chance,” shares Mark about the lifetime experience.

Travis adds, “It was one of my top experiences as far as racing, interpersonal experiences, a spiritual journey, and having fun. It was wonderful. We interacted with locals along the way. We focused on stopping and sleeping each night, especially with the Alzheimer’s, at small, simple concrete houses. You sit down and have tea and chat and go to bed.”

Overall, sleeping well each night helped their team maintain pace and make cutoffs. “As soon as we could get to a dry, warm village to sleep, we knew we probably should. That was balanced with cutoffs along the way. We were constantly looking at those. Overall, because we were sleeping well, all four of us were able to move well in the day. Then we would pass people during the day who hadn’t slept and weren’t thinking straight. Because we were taking care of ourselves with sleeping a lot and eating a lot, we moved well,” says Travis.

Travis (left) and Mark (right) with Bear Grylls (center) at the closing ceremony of Eco-Challenge Fiji.

In addition to participating in the Eco-Challenge Fiji together in sync and as a team, a primary source of therapy for both Travis and Mark has been to continue to run. Now, the 69-year-old runs every day.

“I run every day and many days I run twice. I never run on roads. I run in neighborhoods that I live in. I try to stay out of the way of cars. I want to make sure they don’t hit me. I do repeats everyday, to get as much elevation as I can. I run uphill. I run big mountains if I can. I keep on going uphill. Usually, it’s on a dirt country road,” says Mark, who also started getting tattoos at age 68. His first one reads, “It’s All Good Training,” on his lower arm.

Travis adds that Mark “goes on trails a lot with his friends, and they have a great run group. Dad can’t drive, and one good friend, Marshall Ulrich, who lives in Evergreen, as well, will go with Dad to run the Three Sister Park, Burden Peak, or the Elk Meadow Park area.” Mark also has an indoor trainer that he jokes “is a fake bike that doesn’t go anywhere,” and listens to Willie Nelson while he pedals.

Mark’s Alzheimer’s has continued to progress, Travis shares, including an inability to dress independently, cook, open a can, drive, read, write, bike outside, ski, swim, do a race alone, or go anywhere alone with the exception of the “repeat hill” where he runs down the street from his home. He also struggles to remember most names and faces, buckle a seatbelt, see the edge of a road or trail, eat with a fork, or find things in the kitchen.

Raising two kids in Salida, Colorado, with his wife, Travis is relatively close by and spends time with his dad often. Up ahead, Travis will pursue a handful of ski mountaineering races alongside his burro races and daily runs.

He says, “Being an endurance athlete is sustainable, because I seem to follow my varying interests. Now I’m more running focused, but through pack burro racing, so you’re training for ultrarunning and marathon distance racing and doing it with the donkey.”

Close to a dozen burro races are held annually throughout Colorado, which celebrate the state’s mining heritage, from May to October. Mark says, “They’re a blast and great to watch.” The race series fits well with Travis’s family time. “I’m at a stage of life where my kids are doing their own thing — I’m on the soccer field cheering them on. I coach the high-school mountain bike team,” he says.

The father-son Mark-Travis duo still race together. Recently, the two completed the 2022 Leadville Heavy Half 25k and the Suffer Better 25k. This winter, they’ll aim to do some snowshoe races. Mark jokes that Travis needs to “knock back” his pace in order to not leave him in the dust or be at home by the time Mark finishes. Travis reassures him, they will continue to take every stride as a team and he “won’t make him hitchhike home.”

“It’s too bad that I got Alzheimer’s. I can manage and I can cope. I’m a regular guy. What I do is normal for any other runner. I’ve got a good life. I have a great family. Everything is good. I’m a very happy guy, and I intend to stay that way,” says Mark, with an uplifting smile and persona. His conviction and confidence are so permeable that you believe he’s going to be ok, too.

“We’re going as fast as we can and as slow as we must,” says Travis with regard to everyday life, time together outdoors, and races. “There’s uncertainty with what progresses at what rate. Staying active and staying engaged is huge for anyone to keep doing what they love doing, and how that looks over time will change. And does running help slow the progression of Alzheimer’s? I would say, absolutely: physically, emotionally, and spiritually, having that engagement [is key.] It’s a vehicle toward community, and Dad still has that, and that’s huge to have him connect with his good buddies and with the greater community of runners that is out there,” adds Travis.

For Travis, he recognizes that as a younger athlete there was a phase where he raced at times for fitness, PRs, and glory. Now, it’s ok to focus on other motivators in this new stage of life.

“You choose how you spend your time and at different phases of life, you have different things going on. I balance my own aspirations or goals with what’s best for my family with my own wife and kids and with my parents. It’s all good stuff. For a trail running race, would I rather go with my dad and hang out and have fun in the aspens and chat with people versus running as fast as I can? Definitely,” he says.

Mark continues, “I think Travis and I are both very happy people. It’s the way we think. We look for the good side of things. I still do. I say this frequently, and maybe it’s not true: I think I can get past Alzheimer’s. I’m not going to quit, and I won’t give up. I’ll be at it until I hit the ground.”

For anyone else struggling with a health obstacle or life challenge, Mark says, “You just got to keep at it. Don’t give up. Don’t throw in the towel. Keep after it. I’ll be running and biking as long as I can live. I’ll run around jungles and I’m not going to quit that either. It’s all good stuff, and there’s no sense quitting, so you might as well go on.”

The Alzheimer’s journey includes circular waves of grief, and there continue to be incredibly difficult moments, explains Travis. However, he’s realized how essential it is to balance the unknown of the future with being in and focusing on the present moment.

Mark says, “Don’t quit. It’s as simple as that. And get another tattoo.”

Call for Comments

- Leave a comment to share your Travis and Mark Macy stories!

- Did you find this story inspiring?

- Do you know of other runners who are dealing with Alzheimer’s disease or other similar conditions? How does running integrate with the management of their well-being?