While I love a local race and sleeping in my own bed the night before, I also enjoy heading across the pond for a destination race.

These big trips come with extra complexities that make performing my best a challenge. I’ve arrived early in Chamonix, France, to avoid jet lag only to get a stomach bug during race week. I’ve traveled last minute to avoid picking up waterborne or foodborne illnesses only to have jet-lag-related thermoregulation issues that left me hallucinating in India.

All that said, many of these issues are avoidable while traveling and once you’ve reached your final destination! In this article, we’ll discuss how to protect your athletic performance in the face of travel fatigue and its favorite sidekicks bloating and swelling, jet lag, airborne illnesses, waterborne illnesses, and foodborne illnesses.

What Is Travel Fatigue?

You’ve likely experienced the fatigue associated with a long travel day, whether it’s by car, plane, bus, or train. Travel fatigue and jet lag are two distinct entities that can both occur after long travel that spans more than three time zones (1). Travel fatigue occurs during and immediately after travel, and most commonly causes short-term fatigue and headaches, as well as bloating, gastrointestinal distress, and swelling.

All of this occurs as a result of being exposed to the environments related to travel, including prolonged exposure to mild hypoxia and low-humidity air in airplanes, cramped conditions and cabin noise in most public transport, and the disruption of eating and sleeping patterns due to a long day of getting between points A and B (2).

The dry air that circulates in a plane cabin maintains a super-low humidity of about 15 to 20%, which causes your mucus membranes and skin to dry out. In fact, on a 10-hour flight, you can lose up to about two liters of water just sitting there, making long-distance air travel very dehydrating. To mitigate headaches and fatigue, staying hydrated while traveling is a good place to start (5).

The changes in airplane cabin pressure don’t just affect your inner ears. One of the other side effects of travel is short-term bloating, sometimes referred to as “jet bloat.” While uncomfortable bloating is generally short-lived and takes care of itself, you can avoid eating gas-producing foods immediately before and during your flight.

Your midsection might not be the only region that feels a little swollen during or immediately after travel. Sitting for long periods of time, particularly in a cramped position, can cause blood to pool in the veins of your lower legs (2). This is because veins contain one-way valves to help move blood against gravity back toward your heart. To avoid this, consider wearing compression socks, and getting up periodically to move around.

Finally, protect your sleep during travel to reduce the effects of travel fatigue. This means, take naps when appropriate and increase your sleep quality while traveling by using an eye mask as well as earplugs or noise-canceling headphones and limiting your screen time.

What Is Jet Lag?

Jet lag, while similar to travel fatigue, has more prolonged symptoms. These symptoms range from daytime fatigue, decreased concentration and alertness, continued sleep disruption, and gastrointestinal disturbances, which can increase the risk of injury and illness and significantly impair sports performance (1). These ongoing symptoms associated with jet lag are caused primarily by a mismatch, or a desynchronization, of your circadian rhythm with the time zone of your travel destination (4).

The term circadian rhythm comes from the Latin term circa diem, meaning “about 24 hours,” and speaks to the many physiological and psychological variables in humans that alter rhythmically in each 24-hour day.

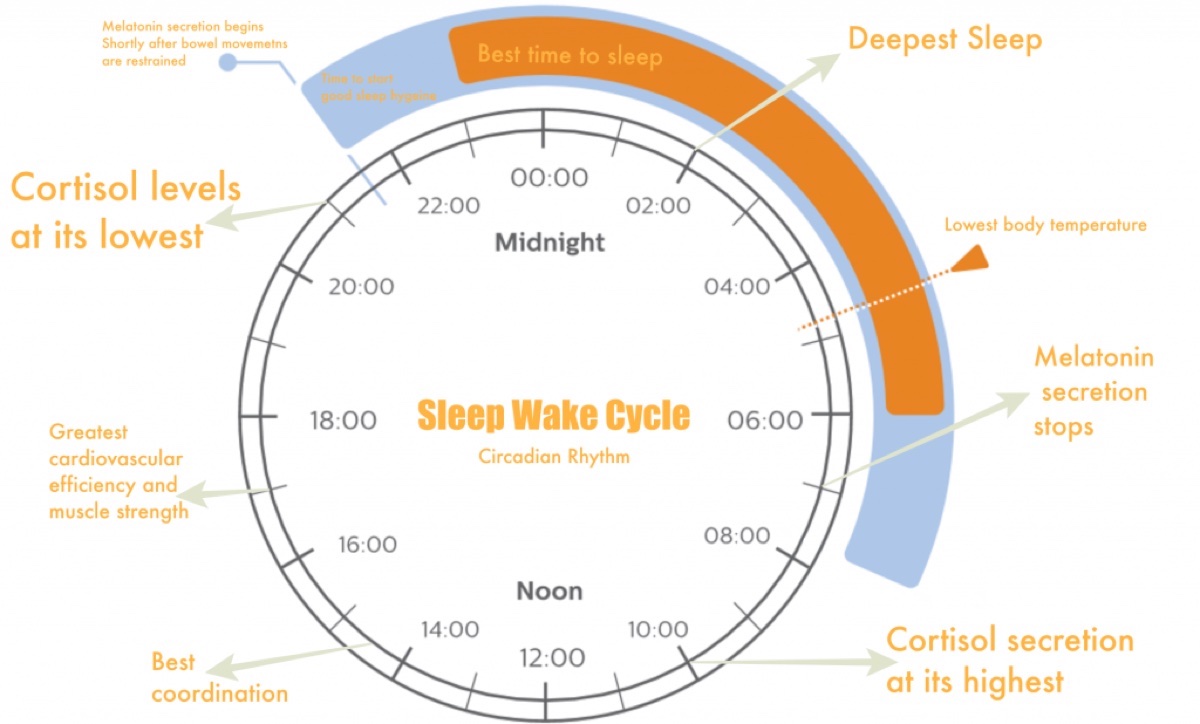

These variables include core body temperature, the hormones cortisol and melatonin, blood pressure, heart rate, hunger, cognitive performance, strength, balance, flexibility, dexterity, subjective alertness, subjective fatigue, subjective sleepiness, and objective sleepiness (4).

Our key circadian rhythm is our sleep-wake cycle and the associated cortisol-melatonin cycle. The portion of your brain known as the hypothalamus is responsible for these reactive cycles, and it relies on environmental signals referred to as “time givers,” such as social contact, eating, physical activity, and the most powerful of them all, sunlight.

As the sun sets, several hours before bed, the hormone melatonin is released from the pineal gland, and helps signal that it’s time to sleep. Without this release of melatonin at the right time, you experience sleep latency, or an inability to fall asleep quickly.

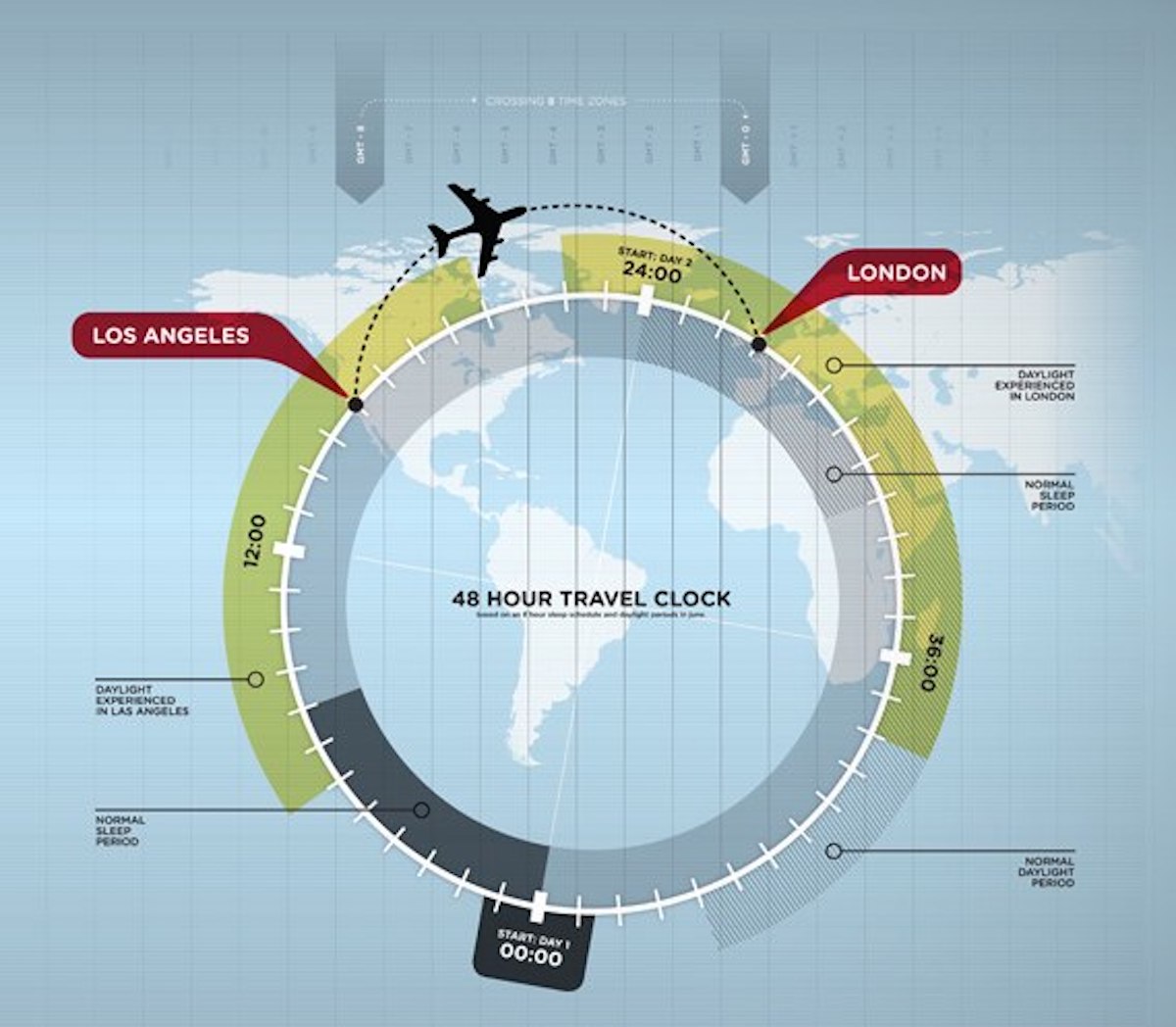

The infographic depicts eastward travel between Los Angeles, California, and London, England, in which the time on the ground upon arrival in London does not correspond with the time at home, specifically when daylight is experienced and when the normal sleep period falls. This mismatch creates the experience of jet lag. Image: Coolinfographics.com/blog/2010/1/22/what-causes-jet-lag-infographic.html

The other major circadian-rhythm influencer is body temperature. Your body temperature fluctuates slightly throughout the day, with your lowest body temperature recorded in the early morning and then steadily rising throughout the day until approximately 9:00 p.m. Sleep onset occurs at the temperature tipping point when the blood flow to your skin increases, dropping your core body temperature.

When you travel westward or eastward through more than three time zones, your internal clock no longer lines up with your melatonin-cortisol cycle or your body temperature cycle, making getting to sleep and staying asleep at night as well as staying awake during the day hard until your circadian rhythm from home matches the 24-hour clock of your new location.

Traveling westward is a little bit easier than traveling eastward, due to the shortening of your day as you skip “forward” through time zones to the east. What this boils down to is that it takes approximately a half-day to recover for every time zone traveled to the west and a full day to recover for every time zone traveled to the east. This is true whenever traveling more than three time zones up until you hit the perfect 12-hour time zone mark.

The cycles of our internal clock not only affect the timing of your sleep-wake cycle, but also the times of day when you are the most coordinated, the strongest, and have the greatest cardiovascular efficiency. Interestingly, this is all usually the best in the late afternoon.

When you travel more than three time zones, the mismatch of your circadian clock puts you off your physiological best ultimately impairing performance.

So, how can we expedite the resynchronization process, avoid performance declines, and even get a jump start on the time change ahead of travel?

Throughout your daily sleep-wake and melatonin-cortisol cycles, we all experience times of peak performance. Image: Holistickenko.com/why-is-sleep-important/

Athletes can get a jump start on travel by getting ahead before they get behind. The first thing you can do is protect your sleep by minimizing the accumulation of sleep debt and by banking sleep ahead of travel.

Next, you can start shifting your sleep, based on the direction of travel, by 30 to 60 minutes per day in the week prior to departure. Once on the ground, utilize the tools you have. Because sunlight is the most powerful time giver, plan light exposure to aid in triggering a phase shift in your circadian rhythm.

Again, continue to protect your sleep, adjusting to your new time zone. You can add naps, but limit them to no more than 60 minutes so as to not impact nighttime sleep. Utilize melatonin supplements of 0.5 to 5 milligrams two hours before bedtime to aid in falling asleep, and utilize caffeine to help with daytime drowsiness.

Finally, consider meal composition: protein-rich meals may help with alertness while carbohydrate-rich meals may help induce drowsiness (5).

Taking proper precautions pre-travel, during travel, and post-travel can help prevent performance decreases due to jet lag and/or illness. Image: Janse van Rensburg, D. C., Fowler, P., & Racinais, S. (2020). Practical tips to manage travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(15), 821–822. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103163 (1)

Avoiding Airborne Illnesses While Traveling

A study following elite athletes found that in traveling to compete in foreign destination events more than five time zones different from the athletes’ home country, they experienced a two- to three-fold increase in the risk of illness, particularly of upper respiratory tract infections (6).

One of the main reasons individuals traveling get sick is due to sleep disruptions and sleep’s impact on our immune system. Additionally, the low-humidity air on long travel days dries the mucus membranes of your nose and mouth, taking out a layer of protection (6).

While we can’t correct your sleep immediately, you can practice good hygiene as you travel and once you reach your final destination:

- Avoid touching areas commonly covered in microorganisms like tray tables and chair headrests. Wipe down those areas prior to use when needed.

- Wash your hands regularly.

- Consciously refuel and rehydrate. This might mean planning ahead of time and bringing the snacks and food you want.

- Avoid shaking hands or other physical contact with people or high-use touchpoints. Sanitize your hands after unavoidable contact.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth unless your hands are sanitized.

- As you travel in the time of COVID-19, follow local and federal mask mandates by wearing well-fitted N95 or KN95 masks.

- Keep current on all your vaccines and check with your primary care provider about illnesses of concern in countries that you are traveling to, including vaccines specific to those areas.

Avoiding Waterborne and Foodborne Illnesses While Traveling

One of the best parts of traveling to new places is new foods and flavors. However, the other side of that coin is potentially experiencing food poisoning and traveler’s diarrhea.

While waterborne and foodborne illnesses can occur anywhere, there are places that come with higher risk, including parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Central and South America, and Mexico. Before any trip, it’s worth checking out your local government’s health guidelines for traveling to your destination.

Gastrointestinal distress is a pretty common outcome of traveling, though there are steps you can take to avoid spending your trip or race on the toilet or in the bushes:

- Heat kills dangerous germs, so eating cooked foods is lower-risk than raw foods.

- Germs require moisture and oxygen to live, meaning dry foods or foods in factory-sealed containers are generally safe.

- Sealed drinks are usually safe, and a carbonated beverage is generally the safest because it means it was sealed properly.

- Avoid ice because it’s almost always made from tap water.

- Choose fruits and vegetables that can be peeled when possible. Otherwise, wash fruits and vegetables with filtered or bottled water and allow them to fully dry before eating them raw. Provide water at small restaurants for staff to accommodate this if possible.

- Carry means of filtering water, whether a filter or chemicals.

- Only eat with sanitized hands.

You may need to travel with a water filter to some destinations, so that you always have access to clean water. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Traveling Athlete Takeaways

- Protect your sleep before and during travel. Avoid sleep debt pre-travel. Avoid blue lights during and after travel to avoid impeding sleeping and/or napping. Use tools to improve sleep quality like an eye mask and ear plugs or headphones.

- Adjust to your new time zone pre-travel. Slowly move your sleep schedule by 30 to 60 minutes a night in the week leading up to travel to adjust to your new time zone.

- Intentionally resynchronize your circadian rhythm once you arrive. Utilize melatonin, light exposure, meal timing, and exercise at your destination to resynchronize your circadian rhythm.

- Be critically aware of illness prevention as you spend time in highly trafficked areas. This includes avoiding touching areas commonly covered in microorganisms and frequently wiping down those areas. Practice good hand hygiene by washing regularly and thoroughly, particularly before and after eating.

- Be cautious of food and water sources. Cook, peel, and/or wash food with purified water when possible. Order food in restaurants carefully, leaning on cooked food when you can’t be sure of how the food was cleaned ahead of time. Drink bottled water and filter or purify any suspect water before drinking.

Call for Comments

- What do you do to stay healthy while traveling? Any particular tips and tricks?

- What extra precautions do you take with COVID-19 being a factor?

Eating fresh food is important while traveling, but a good practice is choosing fresh food that can be peeled or washing your fruits and vegetables with clean water before eating them to avoid waterborne and foodborne illnesses. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

References

- Janse van Rensburg, D. C., Jansen van Rensburg, A., Fowler, P. M., Bender, A. M., Stevens, D., Sullivan, K. O., Fullagar, H. H., Alonso, J.-M., Biggins, M., Claassen-Smithers, A., Collins, R., Dohi, M., Driller, M. W., Dunican, I. C., Gupta, L., Halson, S. L., Lastella, M., Miles, K. H., Nedelec, M., … Botha, T. (2021). Managing travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes: A review and consensus statement. Sports Medicine, 51(10), 2029–2050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01502-0

- Duffield, R., & Fowler, P. M. (2017). Domestic and International Travel. Sport, Recovery, and Performance, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315268149-13

- Sandbakk, Ø., Solli, G. S., Talsnes, R. K., & Holmberg, H.-C. (2021). Preparing for the Nordic skiing events at the Beijing Olympics in 2022: Evidence-based recommendations and unanswered questions. Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise, 3(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-021-00113-5

- Roach, G. D., & Sargent, C. (2019). Interventions to minimize jet lag after westward and eastward flight. Frontiers in Physiology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00927

- Janse van Rensburg, D. C., Fowler, P., & Racinais, S. (2020). Practical tips to manage travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(15), 821–822. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103163

- Svendsen, I. S., Taylor, I. M., Tønnessen, E., Bahr, R., & Gleeson, M. (2016). Training-related and competition-related risk factors for respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections in elite cross-country skiers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(13), 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095398