A totally realistic ultrarunning scenario:

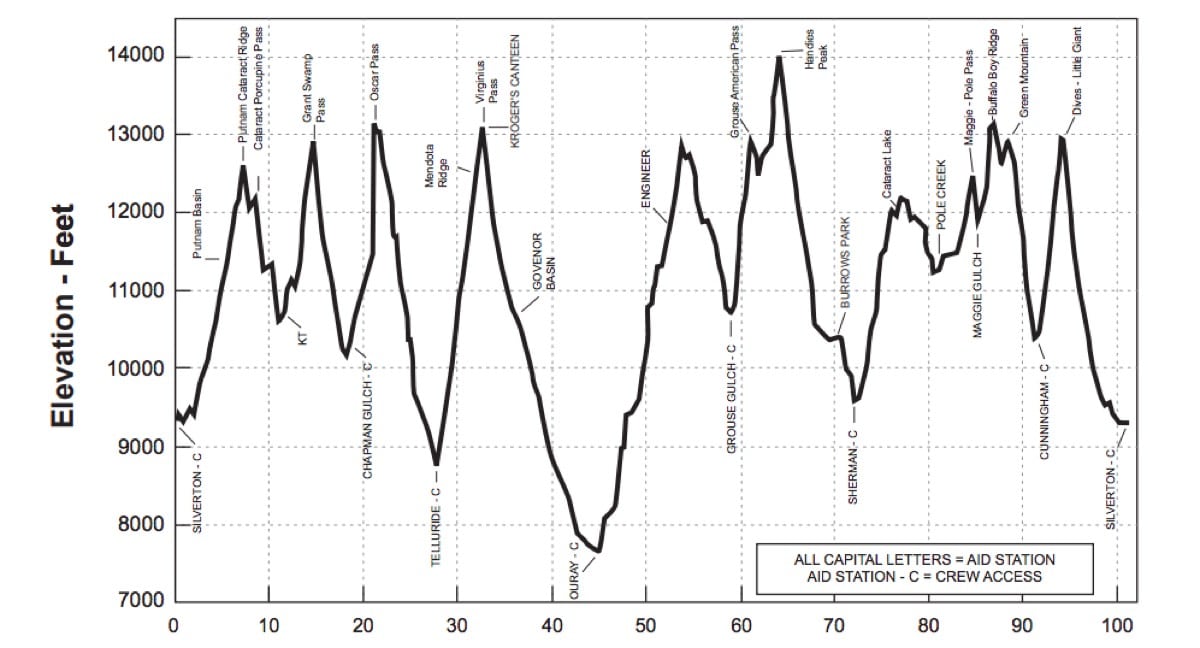

Your buddy finally got selected in the lottery to run the Hardrock 100 after six years of trying, and he asked you to crew and pace him. He’s spent the last month up in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado running sections of the course and acclimatizing. The Hardrock course ranges in altitude between 7,700 feet and 14,000 feet, and the runners spend the majority of their time around 11,000 feet.

There’s no simulating that in San Antonio, Texas (elevation 650 feet) where you both live. You’d planned to drive up the week before Hardrock, but with one thing and another, you don’t make it to Silverton, Colorado (9,318 feet) until the day before the run. You don’t sleep well that night, and when you get up to see the runners start, you have a rotten headache. You don’t feel much like eating breakfast with the rest of the crew. You just feel beat. Honestly, if you’d had more than one beer last night, you’d chalk these symptoms up to a hangover.

You should:

A. Take an ibuprofen

B. Drink some water

C. Suck it up and pack the crew vehicle

D. Drive down to the city of Durango (elevation 6,522 feet)

E. Go to a higher elevation

Choose an answer before continuing.

Answers:

A. Take an ibuprofen

A headache is the defining symptom of mild and moderate altitude illness, also known as Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). The headache can range in severity from 1 to 10 on a pain scale–from “Not Tonight Honey” to “Ice Cream Headache.” Taking an over-the-counter pain medication might provide a little relief. Take the dose recommended on the packaging.

B. Drink some water

Water will not make your altitude-induced headache go away, but it’s easy to become dehydrated at altitude, so go ahead and drink up. There’s no use being dehydrated and having altitude illness. (For the record, a headache is not a common sign of dehydration.)

C. Suck it up and pack the crew vehicle

These are the symptoms of mild and moderate altitude illness:

- Headache (in addition to one or more of the other listed symptoms)

- Nausea with possible vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue or weakness at rest

- Insomnia

They usually improve or resolve within 48 hours (if you don’t go any higher). If you aren’t short of breath while you’re sitting still, or having trouble with coordinated movements (like walking), and you’re not confused or disoriented, then light exercise like packing the car will help with acclimatization.

D. Drive down to the city of Durango (elevation 6,522 feet)

This would alleviate the headache and other hangover-like symptoms. A decrease in elevation of 2,000 feet will usually diminish or relieve symptoms depending on the altitude you started from. Most people don’t have signs and symptoms of altitude illness below 8,000 feet.

E. Go to a higher elevation

This will make your symptoms worse. You feel awful because there are decreased levels of oxygen in your blood due to the decreased atmospheric pressure at altitude. If you go higher, your oxygen levels will drop further, and you will feel even worse.

So the only way to alleviate your headache and other symptoms is to get rid of the altitude. But in this particular scenario, that’s a pretty lame choice. Your symptoms are mild and sucking it up and crewing your friend is a good answer. Taking an ibuprofen for your headache is also a good answer. Staying hydrated is another good answer. (What kind of crappy multiple-choice test is this?) Really, the only bad answer is “Go higher.”

Of course, you are planning to go higher today, and so the scenario continues.

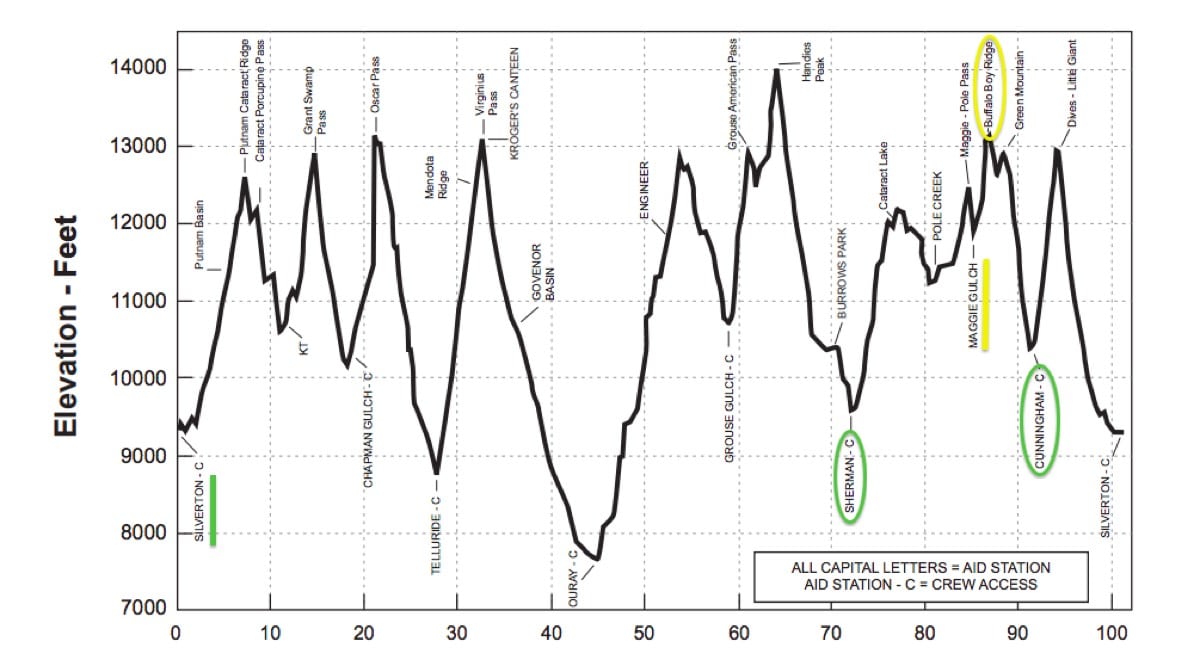

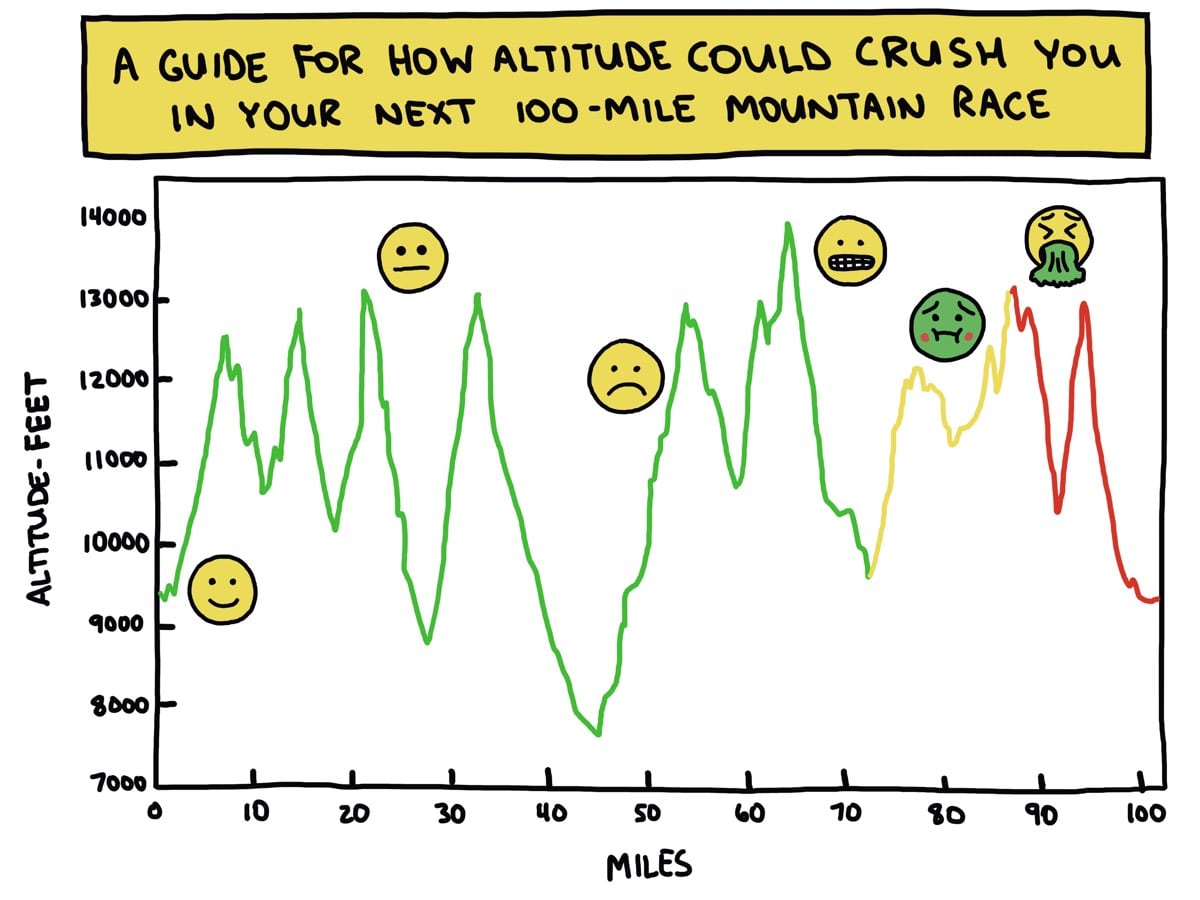

You’re pacing your buddy about 20 miles between the Sherman and Cunningham Gulch aid stations.

A modified Hardrock 100 clockwise course profile showing this scenario. Image is modified from a screenshot from the event’s Runner’s Manual.

You’ll climb and stay above 12,000 for a good chunk of this section. By the time you make it to Maggie Gulch aid station, located midway through your pacing gig, your headache is so bad that you can’t think about anything else. It feels like your forehead is in a carpenter’s vice and every time you turn, it’s like your brain is crashing into your skull. You’ve been vomiting for the last half hour and have to work hard to keep up with your friend’s hiking pace. From Maggie Gulch, you’ll climb above 13,000 feet to Buffalo Boy Ridge before dropping down to Cunningham Gulch aid station.

Should you continue on?

A. Yes

B. No

Choose an answer before reading further. Justify your answer.

Answer:

B. No

You are suffering moderate altitude illness. If you go higher, your symptoms will probably get worse. You are no help to your runner. In fact, in this mountain environment, you are a safety hazard.

But you choose “A.” There’s no way your runner is going to drop you. You’d never hear the end of it. And thus the scenario continues.

You make it over Buffalo Boy Ridge right before a thunderstorm rolls in and lightning traps you and your runner around 12,500 feet. You hunker down behind a rock for almost an hour before it’s safe to move again. By that time, you’ve started to cough. It’s a dry cough. And once you start moving, you can’t keep up with your friend. You lag behind, stopping often to catch your breath. You tell him you just need to sit down for a minute. You’re still having trouble catching your breath as you sit there. You cough some more.

What do you do?

A. Find a safe way to descend NOW

B. Keep going, as it’s only about three miles to the next aid station

Choose an answer before reading further.

Answer:

A. Find a safe way to descend NOW

You have High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). Fluid is accumulating in your lungs. This kind of severe altitude illness can kill you. Symptoms include:

- Decreased ability to exercise

- Persistent dry cough

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Increase heart rate and respiratory rate at rest

- Pale or bluish-colored skin

- A productive cough (late sign)

There are three things you can do to treat HAPE:

- Descend

- Get down

- Go lower

NOW!

If emergency medical services are necessary, they will also administer oxygen.

Finally, the scenario ends. Your friend learned about the dangers of HAPE during a Wilderness First Aid course. He insists you take an old mining road that leads off the mountain and down to the aid station immediately, a shortcut off the course that allows you to descend faster. He runs ahead to see if he can get an ATV to come up the road and meet you. He knows this will mean he’ll miss the time cutoff at Cunningham Gulch. You take the ATV ride to the aid station and then a car ride down to Montrose (5,807 feet).

By the time you reach town, your headache is gone and so is the nausea. You spend the night, and by the following afternoon, you’re no longer coughing or short of breath while you’re just sitting around. If only your ego had been smaller, and you hadn’t kept going higher despite your symptoms of moderate altitude sickness, your friend might be a Hardrock finisher. Oh well, he’ll get back in someday. Maybe. You know how that lottery is. You start your drive back home feeling fine and thinking about the acclimation recommendations in Corinne Malcolm’s iRunFar article Into Thin Air: The Science of Altitude Acclimation.

[Author’s Note: Learn more about mild, moderate, and severe altitude illness and how to prevent it and other wilderness first-aid skills with a two-day NOLS course. Thank you to Tod Schimelpfenig, NOLS Wilderness Medicine’s Curriculum Director and author of NOLS Wilderness Medicine, for his guidance and oversight of this series. Thanks also to graphic artist Brendan Leonard, the trail and ultrarunner of Semi-Rad fame, for his graphics collaboration in this article series.]

Call for Comments

- Have you ever experienced symptoms of altitude illness while trail running or ultrarunning? What did you do to alleviate them and did the symptoms improve?

- Have you ever developed severe altitude illness while running? What was the situation and how did you resolve it?

Image: Brendan Leonard/Semi-Rad