Introduction: The Allegory of The Cut on the Hand

Imagine you cut yourself on the back of your hand. Big ol’ gash. You go to the doctor, who puts in a couple stitches, a nice bandage, and sends you on your way.

Imagine you cut yourself on the back of your hand. Big ol’ gash. You go to the doctor, who puts in a couple stitches, a nice bandage, and sends you on your way.

You’re feeling better: doesn’t ache, not bloody, all is good. So you get a wild hair and tear off the bandage…then “do your normal thing”. In the process…it starts to bleed again.

You go back to the doctor:

“Look doc, it’s bleeding again! Why isn’t it better? There must be something really wrong, I need more tests!”

The doc, quite perplexed (if not annoyed), says, “Well, what happened to my stitches and bandage??”

“Oh, I ripped that off. And it got itchy, so I scratched it for five minutes straight…What do you think is wrong with me? I need an MRI!”

Why isn’t the cut better? Because irritated tissue needs time–and limited stress–to heal!

The Cut represents a visually represented tissue injury. Unfortunately, running injuries often lack such simple transparency.

Last month, we outlined an economic model of injury recovery to aid in explaining the injury healing process. This month, we’ll delve in a little deeper, using yet another analogy to help shed light on the remarkable–if not at times frustrating–process of healing tissue, and why you have to go slow, and why it has to hurt!

The Injured Tissue Construction Project

Injury occurs when tissue fibers that comprise muscle, tendon, ligaments or other soft tissue, tear (or by any other means, are permanently deformed). This phenomenon is independent of pain (which can, and usually does, occur well before actual tissue deformation). Tissues have been torn, and their physical integrity is compromised.

For the sake of this explanation, I will compare the injury process to a sort of natural disaster, where physical structures, such as homes and other buildings, are significantly damaged. The response and repair process to tissue injury is similar to that of a building repair.

Most running injuries are mild to moderate strains, where a fraction of the total number of tissue fibers have been damaged. Imagine holding a hundred pasta noodles in your fist, where ten or thirty, are broken, somewhere in the bundle. This represents tissue strain. Severe injuries, such as tendon and ligament ruptures, represent more thorough destruction, usually through the full thickness of the entire tissue.

Regardless of the severity of injury, all injured tissue healing passes through three fundamental phases. The severity of the injury dictates how long each stage will last:

Inflammation (days 0-20). After the bleeding is clotted, the body goes to work on damage control, bringing in immune cells to clean up any mess, and repair cells and materials to the area. It is the National Guard, coming in after the disaster to establish control and bring relief. This includes increased blood flow and fluid. This response is represented by the cardinal signs of inflammation: redness, heat, swelling, and pain: the latter a result of increased physical and chemical stressors on nerve endings. This stage is crucial in securing optimal conditions for successful tissue repair.

Many physiologists advocate for a fifth cardinal sign of injury: decreased function! It is implied that, because physical tissues are damaged or destroyed, that the overall function of the structure is now compromised, and less functional.

Inflammation controls the area, brings in vital supplies, and sets the stage for repair.

Proliferation (days 10-40). Once the National Guard has established order, the real construction crew arrives. This stage, also known as fibroplasia, involves the migration of fibroblasts–connective tissue “construction worker” cells–to the area to patch things up. Fibroblasts are the skilled carpenters and bricklayers, and their materials include collagen fiber: the bricks, lumber, and sheetrock. They bring along granulated tissue cells: the cement and mortar, nuts and bolts, nails and screws. Granulated tissue facilitates collagen synthesis and new blood vessel formation that helps “stick it all together.”

Several construction foreman, known as macrophages, direct the activities of the fibroblasts and granulated tissue to get to work, patching the new structure. However, in this phase, the initial construction is mostly scaffolding, crude cinder blocks, or even sandbag walls – scar tissue. It represents a temporary structure that is needed for the time being, to provide temporary strength and protection, while the permanent structure is built within.

Temporary plumbing and electrical is also installed. Amidst the granulated tissue are the building blocks for tiny blood vessels that form to aid in building product transport: oxygen and nutrients in, waste products out. Additionally, the body will lay down temporary electrical work–new nerve endings–to “shed light” on the working area.

The beauty of this temporary makeshift structural approach is that it allows us to function during the construction process, albeit on a limited basis. The floors are two-by-four planks: rudimentary, but at least we can get around as the permanent structure is being built. This is what allows an injured athlete to begin being active, gently walking around, even though the repair is far from completion.

Maturation (days 30-300+). This represents the true building and finishing phase. Once adequate scaffolding and temporary structure is formed, the crack construction crew goes about forming the permanent structure. The plywood scar tissue, comprised of weaker Type III collagen fiber, is slowly and methodically transformed or replaced with stronger, more resilient Type I collagen fiber, the finished product of connective tissue found in muscles and tendons. The straw house is transforming to brick.

Type I collagen is superior to Type III in nearly every way–except building speed! Thus, the whole advantage to scar tissue formation is to quickly build a protective temporary structure. The hallmark of maturation is the establishment of super-strong brick, concrete-and-reinforced bar structure akin to normal, healthy tissue.

The stages of healing tissue. Note the tensile strength of the tissue (as a percent of normal) does not improve until well into the maturation phase.

(Musculoskeletal Trauma: Implications for Sports Injury Management, Gary Delforge, 2002, p.30)

Where the construction process gets muddled is during advanced remodeling. The temporary scar tissue scaffolding is immense and must be constantly worked on: to be torn down while also being rebuilt as the stronger Type I collagen fibers. At this point, the burden of the project is that only small, incremental work shifts can be done, alternated by more tearing down. Then, of course, the crews must take a break to eat, drink, and sleep!

This is remodeling stage is the real bear of the construction process, because of the delicate balance of teardown and building, of stress and rest. Too much activity, and you teardown too much, threatening the structure. Too little activity, and the project goes nowhere–insufficient space and materials to build!

The full remodeling process can take a very long time. For lower-blood flow tissues such as ligaments, tendons, and fascia, the process can take a year or longer.

The Botched Remodel: How Inconsistency Undermines the Healing Process

The economics model outlines the partial-yet-progressive tissue healing process: where the building (perhaps a factory) is only at partial capacity, yet still capable of output. So long as the production progress is patient and gradual, consistent investments will allow the renovation to progress.

But injured runners are seldom patient and often inconsistent in their approach to injury management.

What happens?

They rush to return. Once the pain has subsided in the slightest (post-inflammatory), they resume normal activity. But running on newly formed scar tissue is like treating the plywood like a concrete structure that it is not. The structure quickly fails–the roof caves in–and they are back to square one.

They over-remodel. Those that are patient enough to ride out the early stages to remodeling, then get greedy: after logging a few conservative, pain-free runs (of adequate, but not excessive remodel stress), they declare they are healed, and return to business as usual. Trying to run their “normal distances,” they overload the partial healing and re-injure the tissue.

They shut down construction! After a few over-load setbacks, many runners will freak out (“There must be something really wrong!”) and completely shut down: doing next-to-nothing, or limping around, compensating in attempts to protect the sensitive area.

The only problem is, this patient, progressive teardown stress is requisite for healing. Without any tissue loading, healthy remodeling cannot continue! The construction site gets shuddered: the workers are going home! Ironically, a total lack of activity–coupled with bits of limping and compensation–can actually make the perceived pain worsen! More pain, less activity, more pain… Given enough inactivity, the vulnerable, semi-complete structure begins to degrade.

And so it goes: rushing, over-stressing, freaking out, shutting down. Does this sound familiar to anyone?

Can you imagine the effect on the perfectly good (and highly skilled) construction crew? All they want to do is build, to have a consistent in-flow of supplies and out-flow of trash, and to finish the job. But many injured runners seldom give them the chance.

And so the restoration job drags on.

Riding Out the Remodel: A Guide for Runners

Successfully navigating the tissue injury remodeling process requires following four simple principles:

- It’s got to be gradual!

- It’s got to be [a little] painful!

- It’s got to be consistent!

- It’s got to be relentless!

It’s got to be gradual! As indicated in the graph above, the tensile strength of healing tissue is a fraction of normal. Thus, remodel stresses must initially be very small. At first, it is simply walking around, but only for short periods. Then, engaging in a normal (non-athletic day).

If you have any doubts: get off of it! Use crutches (or if you have to, a wheelchair!). For those of you with a foot or lower leg injury, get a walking boot! All these tools–even a simple cane–can unload the tissue enough to facilitate healing. A day or two of assistives might save you weeks in recovery time!

Then, once on your feet, all periods of stress must be followed by rest! Healing tissues are like newborn babies: they may drink a liter of milk a day, but not all at once! Small bits of eating, crying, sleeping, eating, crying, sleeping… Stress and rest bouts must be small, yet frequent.

If you’re on your feet for work, plan periods every hour (or less) where you can sit and rest for at least five to ten minutes. Once you return to running, carve out at least thirty minutes of rest time afterward to let the stress absorb.

By doing so, you greatly enhance the tissue’s ability to tolerate activity. With short bouts of rest and a limit of, say, an hour, you might be able to be on log for six to eight hours feet time. But if you plow through for two hours, you may flare. Likewise, a four-mile run may be optimal if followed by a half-hour’s rest; whereas rushing back to work after the same run will result in overload.

Stress, then rest! Stress, then rest! Stress, then rest!

It’s got to be [a little] painful! The remodeling phase is often painful. In fact, I argue that it must be painful, for a couple reasons:

First off, during the end-stages of proliferation and throughout maturation, fibroblasts engage in a process of contraction. Contraction, in a literal sense, is the pulling-together of borders of the wound, or of adjacent tissue fibers, in order to strengthen the tissue connection. This is a constant process during these stages. And while critical to increasing strength, it can be painful.

Runners in the middling stages of healing may complain of their healing plantar fascia or Achilles as “always being tight,” and requiring constant stretching. It very well may be that they are feeling the effects of constant tissue contraction (and may also be the impetus behind night splints, which in effect combat the contraction process–for better or worse).

The remodeling phase is also painful because of the number of associated nerve endings (which sometimes grow in number in an injured area) and temporary blood vessels surrounding the structure. The constant remodeling–while integral for a strong permanent structure – can trigger these nerve endings, eliciting pain.

For these reasons, the sensitive tissue will be painful with most any activity, yet that activity is still safe. The tissue craves those short bouts of activity–to counteract contraction, and inevitably de-sensitize those extra nerve endings.

And so long as pain does not increase and persist–remaining elevated for prolonged periods of the day, or worsen the next day–tissue tolerance has not been exceeded.

It’s got to be consistent! Consistent, small bouts of stress-then-rest is the fastest way to recover. It is the balance of teardown and build-up. Overload and freakout represent extremes that both result in remodeling slowdowns. Keep activity disciplined and consistent, and repair will progress smoothly.

Then, as the days go by, the tissue can gradually handle more stress. But don’t fool yourself! The tissue is not magically healed! Remember the construction analogy: the plank floor has been replaced by concrete…but has the concrete had time to fully cure? Often times bouts of tissue loading may feel 100% pain-free, only to produce delayed-onset pain and swelling. Mind the response for the rest of the day and next day, in order to “test the structure!”

Once it’s time to run, you have to do mini-runs: a single mile, maybe less. The same rules apply: gauging effect from the “workout” for the rest of the day. Should the sensitive tissue feel no worse, proceed with caution. But the goal is to feel a little better tomorrow, so be on the lookout for increased soreness, a sure-sign of excessive strain.

It’s got to be relentless! Overcoming injury is not for the faint of heart. All aspects of this approach are painful: the patience to stop running, the tedium of restorative exercises and micro-runs, and the physical pain of the remodeling process.

Listen to your body, but fearlessly soldier forward!

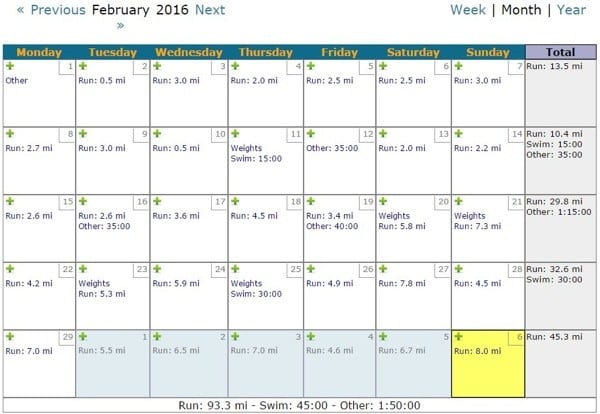

Below is a sample of my progressive return to running from a serious plantar fascial injury:

Caption: The author’s training log for the month of February 2016. Overcoming a significant plantar fascial injury required several weeks of no running, followed by this painfully-gradual progression. Courtesy, Joe Uhan’s running log: www.running-log.com

At no point during this progression did I have a pain-free day. Something was always symptomatic. However, symptoms were always minimal:

- slight soreness in the morning

- slight soreness with prolonged standing at work

- moderate soreness an hour after running

- slightly soreness at the end of the day

Regardless, I managed tissue loading with frequent bouts of stress, always (whenever possible) followed by a period of rest. And as you can see, my tolerance for running gradually improved from nothing to well over an hour (with intensity) by month’s end. But better yet, it is nearly 100% pain-free!

It’s been a successful remodel thus far, but will require ongoing discipline and consistency over the next couple months to ensure progressive healing.

* * * * *

We ultrarunners like to go long, or go home. The growth of the sport might be based on the notion that a marathon isn’t far enough, and the explosion of hundred-milers, previously sparse (as well as the development of two-hundred milers), may be due to the notion that a mere 50- or 100-kilometer race is somehow not enough.

So when I tell injured, recovering runners in my clinic, “You get to run a mile today”, I am often met with furrowed brows and incredulous stares.

Their reaction: “A mile?? What’s the point?”

Most of us run long for the experience: of getting away, of having the time, and the drain–of internal energy and external stressors–to cleanse the system and renew.

Additionally, ultra-distance runners like to experience pain, as long as it’s on their terms. Pain of pace, distance, or terrain is good pain. Stabbing, aching, grabbing, burning pain of tissue strain is a different matter–not what we bargained for.

So when ultrarunners get hurt, it’s a whole new challenge: who has patience, discipline, and fortitude to survive a game of micro-progressions?

But if you can frame the healing process like an ultramarathon training build-up–and patient, gradual process inherent–you’ll be better able to embrace the challenge and ultimately emerge victorious.

(Bibliography: Musculoskeletal Trauma: Implications for Sports Injury Management, Gary Delforge, 2002)

Call for Comments (from Bryon)

- Which aspect of injury management do you most often fail at: rushing to return, over-remodel, or shut down construction?

- Do you tend to overstress recovering tissue or freakout about the accompanying pain and disfunction?