Nearly every scientific research article I’ve pulled on the topic of “aging athletes,” “masters athletes,” and even “staying healthy as we age” contains some form of the phrase “age related decline” in the introduction. Everywhere we look, masters running is framed as a process of decline and we rarely talk about understanding and optimizing masters runners’ present potential in the same way that we do with younger runners.

While it’s scientifically true that aging affects our bodies and thus our running performance, we also know and have written in this column about how our psychology impacts athletic performance, with negative self-talk and low self-confidence leading to non-optimal performance. How can this negative, decline-centric approach possibly benefit masters runners?

All of this has us thinking, is there a way to flip the narrative and use the information that science teaches us to live and run optimally at every age?

In this article, we attempt to do this. We examine the physiology of aging and athletics, learn how to optimize our running at older ages, discuss the overall health benefits of maintaining our athletic pursuits as we age, and suggest ways our whole community can best support older runners.

Ragna Debats on her way to placing third and setting a masters record at the 2021 Western States 100. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Why is Learning About Masters Athletes Important?

While diving into this topic could be self-serving as the clock stops for no one, the truth of the matter is that since the 1980s there has been a continual increase in the number of master athletes — athletes 40 years of age and older — in endurance and ultra-endurance running events. Often in these events, the percentage of finishers over 40 years old is frequently higher than those under 40 years old (1).

Additionally, while the average age of elite track-and-field athletes and marathoners is around 30 years old, the age of peak performance in ultra-endurance events generally increases as the race distance increases.

All of this includes athletes in their seventies finishing races like the Western States 100, Leadville 100 Mile, and UTMB, as well as athletes in their forties winning major races and setting national and world records (2).

Research loves masters athletes, because we serve as clear examples for why and how continuing to run and train into our sixties, seventies, and eighties is important. There is ample research on masters endurance athletes that highlights how our style of physical exercise, which is above the recommended 150 minutes of moderately intense exercise per week, greatly increases longevity and protects us from disease (9, 11). This is because this style of training allows us to attenuate muscle aging and maintain a higher maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) (9). Also, very simply put and as we’ll talk about shortly, continuing to carry out traditional run training that includes both endurance and high intensity running allows us to perform our best too.

We have talked at length in this column over the years about the mental health benefits of running, and this remains deeply true for masters runners. Maintaining this level of physical activity reduces stress, increases social functioning/satisfaction via connection and identity, and increases feelings of vitality in masters athletes (7).

Finally, increasing knowledge about masters athletes as a community, whether you’re a masters athlete now or will be in the future, allows us as a community to better support each other.

Physiological Factors at Play for Masters Endurance Athletes

How Aging Affects Our Physiology

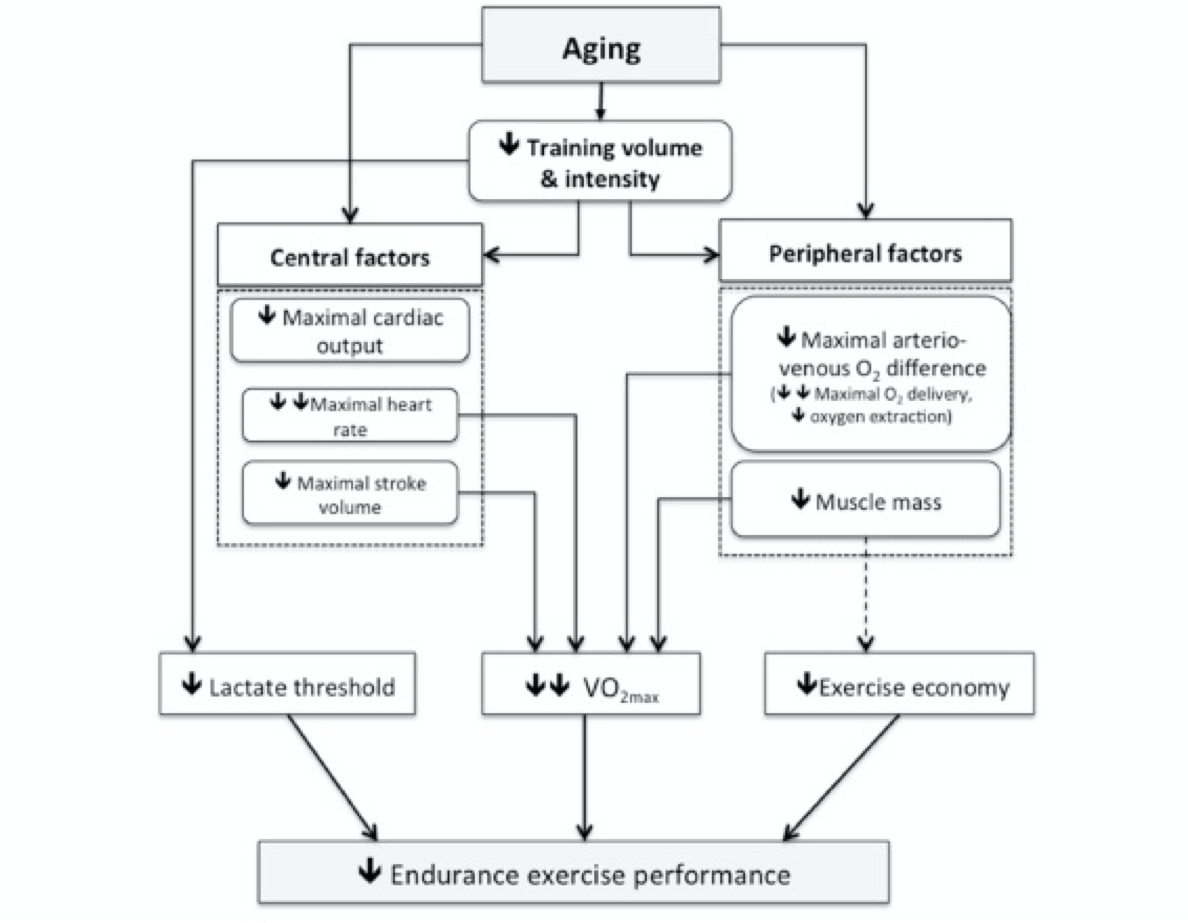

Like many things in physiology, the effects of aging are multifactorial. A combination of changes to central (cardiovascular) and peripheral (oxygen extraction/utilization) factors as well as physical (prevalence of injury, time spent at different training intensities) characteristics all impact performance decade to decade (1).

Zooming out, what this looks like is, if we are unable to maintain the same volume and time at intensity as we age, we naturally see a decrease in lactate threshold which is also referred to as ventilatory threshold or the point at which lactate starts to accumulate in your blood, VO2max or the amount of oxygen the body can utilize during exercise, and exercise economy or the energetic cost of running.

Zooming in, lactate threshold is impacted predominately by a decrease in training volume and intensity. This means, it’s highly trainable in the masters athlete. However, VO2max is impacted by both training volume and intensity as well as by sarcopenia or the natural, age-related decrease in lean muscle mass.

As we have talked about in this column before, sarcopenia rapidly accelerates after 40 years of age and it decreases our ability to deliver and extract oxygen (predominantly impacting your mitochondria), cardiac output (the amount of blood pumped through your heart per minute), maximal heart rate (decreases at about 0.7 beats per minute per year independent of activity level), and stroke volume (how much blood you pump with each heart contraction) (1, 2, 3, 4).

In healthy but sedentary adults, VO2max naturally decreases at about a rate of 10% per decade after 30 years of age, but as we said maintaining both endurance and high intensity training can greatly reduce that, with testing showing that octogenarian lifelong endurance athletes maintained approximately double the VO2max of untrained octogenarians (1).

Finally, the last piece of the performance puzzle is exercise economy or locomotor efficiency. While likely to contribute much less compared to VO2max or lactate threshold, the energetic cost of running can’t be overlooked. When comparing 28-year-old and 60-year-old triathletes, researchers found the average energy cost of running to be about 11% higher in the masters athletes (6). Interestingly this is due more to a decrease in muscle power (due to decrease in muscle mass via both muscle size and number of muscle fibers) and not the plasticity of the muscle fibers themselves (5).

While the primary factor in maintaining endurance performance as we age is training volume and intensity, this graph shows how impacts can be further broken down into central and peripheral factors that impact lactate threshold, VO2max, and exercise economy. Image: Lepers R and Stapley PJ (2016) Master Athletes Are Extending the Limits of Human Endurance. Front. Physiol. 7:613. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00613 (1)

How Masters Athletes Can Best Use Physiology to Optimize Performance

Faced with the sometimes harsh wording of the academic literature, I reached out to a mentor of mine, runner, former Western States 100 medical director, researcher, and physician Dr. Marty Hoffman, 65 years old, for his take on optimal running in masters athletes.

“As you know, the science is clear that a decline with aging is inevitable, but regular exercise reduces the rate of decline. One can still maintain considerable functional capacity that can also be quite satisfying if goals are appropriately adjusted. People may not only adjust performance goals (such as accepting a slower race time), but may also recognize that there can be other more valuable things to do for many hours each weekend, and still stay quite capable (and perhaps healthier) by only exercising the same amount of time spread across the entire week.”

But what about the masters athletes who wish to push boundaries with their run performance and run as optimally as possible — in addition to pursuing our overall health and wellbeing?

If the main culprit behind changes in performance are changes to muscle mass, then preventing or slowing those changes are in our best interest. Again, this is why strength training becomes even more important as we get older.

Changes in muscle mass are not the only change occurring. As we age, our ability to synthesize protein decreases, vital for repairing and remodeling skeletal muscle, which ultimately impacts our ability to recover as quickly as younger athletes (12). Because of this, the spacing between hard sessions and the timing of protein ingestion post-training is also more important (12). What this means in practice is that you may only be able to do one hard workout a week instead of two or three, and that you should consider ingesting 20-plus grams of protein immediately after a long or hard session (12).

The important thing here is to recognize that lots of individual variability exists and that it’s not “only x instead of y,” it’s about being able to consistently train without risk of injury, which as we all know is important independent of age.

A Note on the Importance of Avoiding Injury as We Age and Run

As we’ve mentioned several times, one of the greatest things that can impact endurance performance over time is the ability to maintain training volume and intensity. One way to do this is to stay healthy and avoid having to take long breaks due to injury or other setbacks. But with other physiological changes taking place, are their specific things a masters athlete should be aware of?

As we age, we experience a progressive decrease in tendon and muscle elasticity and a decrease in the overall size and total number of muscle fibers. This leads to less lean muscle mass and therefore a reduction in power and strength (5). We also begin to experience greater joint stiffness and subsequent biomechanical changes, which can result in imbalances that affect both walking and running gait, thereby increasing our risk for injury (5).

What’s the best way to combat this? Try to maintain muscle mass and subsequently muscle strength, and the best way to do this beyond staying active is to put a great emphasis on strength training as we age.

Finally, while rehabilitation protocols for young athletes and masters athletes might be more or less the same, slower recovery times in masters athletes may require more nuanced decision-making for the return-to-running timeline post-injury.

Psychological Considerations for the Masters Athlete

Psychology and the Masters Athlete

The other piece of the puzzle is behavioral characteristics, predominantly a reduction in time and motivation to train.

We’re not sure we can help you with the time piece of that puzzle, as we all know that free time to run can be a challenge to carve out of busy masters athletes’ lives as we simultaneously juggle families, apex points in our careers, and a host of other worthy responsibilities.

But we can discuss the motivation aspect. It’s easy to get bogged down when the scientific literature and media we consume utilize words like “insidious decline” and in surveys of masters athletes over the past two decades, it’s clear that this language is absorbed and sticks with us.

In these surveys, masters athletes reported encountering ageist attitudes from others (being told they are too frail to participate) and that these attitudes became integrated into their own perceptions of themselves putting up barriers to sport and exercise (7).

Or as put by researcher Dr. Sean Horton, 52 years old, “Many adults ‘buy into’ these negative stigmas, internalize them, and avoid adult sport as they get older regardless of whether they have the ability to participate.” (7, 10). All of which impacts motivation to exercise, train, and race. So how do we combat that?

How Masters Athletes Can Best Use Psychology to Optimize Performance

I reached out to friend and colleague Neal Palles, LCSW, 53 years old, who is a runner and a clinical social worker and therapist who specializes in sports performance, about coming up against these ageist ideas.

“We’re coming back to this idea of acceptance: it’s going to happen, it’s going to bring up uncomfortable feelings. And it’s important for us to remember this isn’t the laying down and giving it up acceptance, but instead acknowledging and opening up to the uncomfortable thought, feeling, and experience.

“You don’t have to let those feelings control you. Come back to where you are right now. Compare [yourself] to your peers, not someone 10 years younger, not the younger you. Be here now. When the uncomfortable feelings come up, notice them, name them — move toward what’s meaningful for you. They should not inhibit you from chasing goals.

“The folks who are over 60 or 70 years of age and killing it recognize and accept they are slowing down, but still focus on those controllable things: rest, recovery, interval training, strength training, nutrition, and more. Yeah, they’ll be confronted with it but they go toward what they love and value in spite of all this. They keep moving forward!”

So while there isn’t a step-by-step guide to tackling the psychological impacts of aging, what Neal says rings true, “I think that part of this idea of acceptance is holding oneself kindly. To recognize that, yes, we are human, this will impact all of us at one time or another. Beating ourselves up, ramping up our training, and doing everything we can to avoid the human part that gets us in trouble. Acknowledging the fear, pain, and the sadness of loss of identity and holding oneself kindly (another way of saying self-compassion) can be a powerful tool to embrace — allowing us to take the next step with what’s controllable here, and dig deep into what gives us meaning.”

A Note on How the Running Community Can Best Support Masters Athletes

We are a product of both our external and internal environments and we know that ageism is a real external impediment for older adults in most modern societies, including in sports. This has us wondering, is there a way for the running community to support masters athletes as well as we do our our younger runners?

I reached out to Liza Howard, a 50-year-old runner, coach, wilderness first aid instructor, nonprofit leader, mom, and an almost-decade-long member of the iRunFar team. For several years, she’s been documenting masters runners in her iRunFar column Age-Old Runners, and so I wondered about her thoughts on how the community can come together to show masters runners that they are a critical part of our sport.

“I think being able to race and participate in our community like we always have is key. The COVID-19 pandemic really made clear how a lack of racing and gathering at races can impact people’s motivation to keep running.” This is a sentiment that I think resonates with all of us, independent of age.

When thinking about how this could be implemented, Liza laid out four clear ways races and race directors could encourage more masters athletes to continue to race as part of our community:

- “Races should make age-group records easy to find on their websites.

- Races should list and highlight age-group results.

- Race directors should evaluate whether their cutoffs prohibit runners in their fifties, sixties, seventies, and eighties to finish their races. If they do, do they want to change the cutoffs to allow more older runners to participate?

- If there are a series of distances at a race, is it possible for the shorter races to have the same overall cutoff as the longest race? For example, if there’s a 50-mile and a 50k race, can the 50k have the same cutoffs as the 50 miler to allow older runners to participate?”

My immediate response is that this resonates with everything I’ve heard from the athletes I get to work with who are racing well into their seventies and eighties. We should continue to intentionally build this and other kinds of community infrastructure to best support masters runners.

Preaching to the Choir: How Running Keeps Us Healthy as We Age

While we might be at an increased risk for injury as a masters athlete, this is often outweighed by a long list of positive outcomes. From chasing PRs to getting out on trails you love, the benefits of running for masters athletes are undeniable, both for physical health but also for mental health and wellbeing. This is so much so that physicians in the U.S. and Canada are giving out nature prescriptions to encourage people to move their bodies and spend time outside (8).

We know that maintaining regular physical exercise also puts you at a decreased risk for clinical depression and anxiety as well as cardiovascular and metabolic disease. It also helps you to maintain bone density and delay muscle aging (5).

When evaluating masters-aged marathoners compared to their sedentary counterparts, the active athletes had substantially greater physical capacity, better long-term health outcomes, higher motivation and psychosocial perspective, and better fought the dogma and negative stereotypes aging (5).

I know we are preaching to the choir here, but running is profoundly beneficial at almost every age, so let’s do all we can as individuals and as a community to support our masters runners.

Call for Comments

- If you are a masters athlete, could you share what’s working for you with your run training and racing?

- What ideas do you have about how the running community can best support our masters athletes?

References

- Lepers R and Stapley PJ (2016) Master Athletes Are Extending the Limits of Human Endurance. Front. Physiol. 7:613. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00613

- Knechtle B, Lepers R, Nikolaidis PT and Sousa CV (2021) Editorial: The Elderly Athlete. Front. Physiol. 12:686858. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.686858

- Lepers R, Burfoot A and Stapley PJ (2021) Sub 3-Hour Marathon Runners for Five Consecutive Decades Demonstrate a Reduced Age-Related Decline in Performance. Front. Physiol. 12:649282. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.649282

- Foster, C., Wright, G., Battista, R. A., & Porcari, J. P. (2007). Training in the aging athlete. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 6(3), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.csmr.0000306468.72466.af

- Gomes, T. L., Viana, L. O., Ferreira, D. M., Inada, M. M., Laurito, G. M., & Piedade, S. R. (2021). The aging athlete: Influence of age on injury risk and rehabilitation. Management of Track and Field Injures, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60216-1_31

- Peiffer,J.,Abbiss,C.R.,Sultana,F.,Bernard,T.,andBrisswalter,J.(2016). Comparisonoftheinfluenceofageoncyclingefficiencyandtheenergycost ofrunninginwell-trainedtriathletes. Eur.J.Appl. Physiol. 116,195–201. doi:10.1007/s00421-015-3264-z

- Young, B.W., Callary, B., & Rathwell, S. (2018). Psychological considerations for the older athlete. In O. Braddick, F. Cheung, M. Hogg, J. Peiro, S. Scott, A. Steptoe, C. von Hofsten, & T. Wykes, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. Online publication. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.180

- Kondo, M. C., Oyekanmi, K. O., Gibson, A., South, E. C., Bocarro, J., & Hipp, J. A. (2020). Nature Prescriptions for Health: A Review of Evidence and Research Opportunities. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124213

- Vancini, Rodrigo Luiz; dos Santos Andrade, Marilia; de Lira, Claudio A B; Theodoros Nikolaidis, Pantelis; Knechtle, Beat (2022). Is It Possible to Age Healthy by Performing Ultra-endurance Exercises? International Journal of Sport Studies for Health, 4(1):e122900. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5812/intjssh.122900

- Horton, S. (2010). Masters athletes as role models? Combating stereotypes of aging. In J. Baker, S. Horton, & P. L. Weir (Eds.), The masters athlete: Understanding the role of sport and exercise in optimizing aging (pp. 122–136). London, UK: Routledge.

- Edward R. Laskowski, M. D. (2021, September 22). How much exercise do you really need? Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 13, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/expert-answers/exercise/faq-20057916

- Reaburn, P. (n.d.). Masters athlete. We’ve Proved It – Older Athletes DO Take Longer to Recover | Masters Athlete. Retrieved March 13, 2022, from https://www.mastersathlete.com.au/2017/03/weve-proved-it-older-athletes-do-take-longer-to-recover/