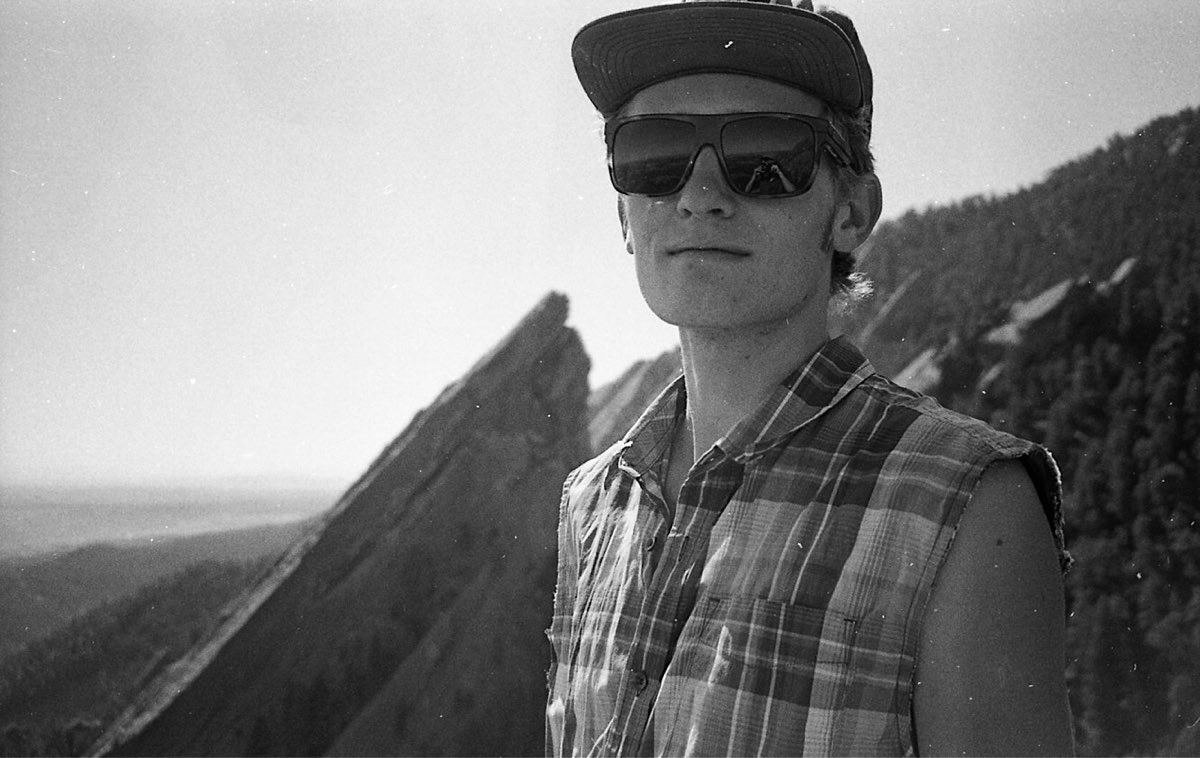

On a pleasantly warm fall day in Boulder, Colorado, Kyle Richardson and I run up the trail from Chautauqua Park toward the Flatirons–the iconic rock formations that grace the city’s western skyline. The monolithic east face of the First narrows into our line of sight. In our peripheral vision, the pointy summit of the Third juts up into the sky like an arrow shot west.

The first few hundred feet of the trail doesn’t provide much of a warm-up. The grade is steep and the path often crowded. We try to keep the pace conversational while weaving between people. In the summer of 2017, the trail received a necessary resurfacing, and the once-pothole-riddled, eroded track is now smooth like pavement. The even ground offers a slight edge to time-sensitive scramblers looking to shave a few extra seconds off their roundtrip efforts.

Kyle’s progression of the First Flatiron fastest known time (FKT) is not measured in seconds, but in minutes. He recently ran from the trailhead to the summit and back in just over a half-hour, taking a full two minutes off Matthias Messner’s previous standard. He pulled off a similar and arguably an even more impressive feat on the Third Flatiron just a few weeks prior.

However, Kyle, isn’t just your average endurance junky. He studied percussion at the University of Colorado Boulder and weaves artistic elements of his music into his mountain craft. A diligent dedication to practice and fine tuning of his mind and body have coalesced in his drumming patterns and his rhythm on rock.

Scrambling blends the high-intensity effort and speed of a runner with the skills and perfection of movement of a climber into one dynamic, edgy cocktail of hurt and pleasure. While the activity is undoubtedly niche, it brings commonality to a shared experience of runners and climbers in the mountains. Boulder has a long history of such rowdy proclivities with the Flatirons being at the heart of these deviances. Many greats have tested themselves on these formations, so while the casual observer might not discern the brilliance of Kyle’s concertos, they truly are at the tip of the spear.

We reach the base of the First in a pedestrian 15 minutes. If we were racing, Kyle wouldn’t break stride between dirt and rock, and even with my best effort, he’d already be out of sight. Today, he pauses, sitting on the edge of the steps to wipe his shoes clean of dirt and an oily sheen that is a bio-product of the trail resurface. In a game where sticky rubber and friction play an integral part in keeping a scrambler on the rock, this attention to detail is paramount.

With over 300 ascents of the First, it would be easy for him to become complacent. Time trials are a rare occurrence, performed only when conditions, fitness, and skill intersect at their apex. Mistakes are uncommon with that kind of acuity of focus, but a safe practice hinges on the attention given to the casual, more banal days.

Kyle springs to his feet, and with a two-step smeary skimper, locks his left fingers on a protruding crystal, using his momentum to drive himself up the near-blank first 15 feet of rock.

A slabby sea of stone stretches above him as he begins his recital. His long limbs and lean musculature, tension and release, under an intricate sequence of hand and foot placements.

His relentless dedication to his practice allows him to move like water. Watching him swim up the rock with such ease obscures the difficulty of mastering the finer nuances of rhythm and flow.

Kyle marches to the beat of his own drum. His tempo is fierce, wild, and near impossible for most to follow.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

Does running or movement in the outdoors sometimes feel like an art to you?