Like this article? Get your copy of the book “Where the Road Ends!”

Welcome to this month’s edition of “Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running,” where we’re talking about training for trail running.

“Where the Road Ends” is the name of both this column and the book Meghan Hicks and Bryon Powell of iRunFar published in 2016. The book Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running is a how-to guide for trail running. We worked with publisher Human Kinetics to develop a book offering the information anyone needs to get started, stay safe, and feel inspired with their trail running.

The book Where the Road Ends teaches you how to negotiate technical trails, read a map, build your own training plan, understand the basics of what to drink and eat when you run, and so much more.

This column aims to do the same by publishing sections from the book, as well as encouraging conversation in the comments section of each article. We want you to feel inspired and confident as you start trail running as well as connected to iRunFar’s community of off-road runners.

In this article, we excerpt from Chapter 9 and talk about building your own training schedule. Even if you want your trail running to be entirely free and unstructured, the casual application of the principles in this chapter will help you maintain a sustainable and long-lasting relationship with running.

Building a Training Plan

Some trail runners run off in search of fun without any real structure to their training. Heck, most trail runners probably don’t think of what they’re doing as training at all; they see their running as a simple act of moving through beautiful places. But for trail runners who want to add a framework to their trail running, a structured training plan can be as fun as it is rewarding.

Building and following through with a training plan can maximize your fitness, increase your speed and strength, build your confidence, give you the edge in trail races, help prevent overuse injuries, and more.

Even with a structured training plan, you choose your own routes, run with friends, take in the sights, and ditch the plan and embrace spontaneity when you desire.

Periodization Primer

As much as there is to love about trail running, we all know that the sport is mentally and physically taxing. We need to rest and occasionally take time away from it to stay healthy. Periodization is the organization of your running that balances periods of focused training with necessary rest.

First, let’s consider the periodization of short time frames. Max King, the 2011 World Mountain Running Champion, who has had success running on the track, roads, and trails, recommends that we organize our training into four-week blocks.

“Studies have found that the body responds best to three weeks of increasing training followed by a week of decreased volume. I like to stack three weeks together increasing volume or intensity by five to 10% per week followed by a week of decreased volume and intensity that is equal to the first week of the block, or about 70% of the maximum week. This four-week training block allows people to increase volume slowly while working on each physiological system and specific workouts targeted to their goals.”

Max King after setting a then-100-kilometer American record at the 2014 IAU 100k World Championships. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

The weeks of decreased volume that King describes allow your body to assimilate the hard work you’ve been doing, give little aches and pains a chance to heal, and offer a reprieve for your mind. If you find that three weeks of hard work and one week of recovery is a bit too much for your body to sustain, shorten the work part of this periodization to two weeks and follow that with a recovery week.

About longer-scale periodization, King explains, “Many athletes periodize their training into three- to six-month blocks depending on their seasons and races planned. These longer periods of buildup allow athletes to reach closer to their potential but also limit the timeframe they can race at or near peak fitness.”

Your running cycles may be defined by the seasons if your off-season running aligns with your participation in winter sports. Perhaps you schedule some intentional time off from running.

If you’re looking to crush some big trail races or take on a major new challenge — we’re talking about anything from a 10k to a trail marathon here — it’s best to stick to three or fewer major outings per year. If you have any more big events on your calendar, you may not be able to train specifically enough for them, or your body may not be able to recover fully from them.

You can still run other races as part of training for your goal events, but you probably won’t be at your fittest for them. When building toward a big goal, divide your training block into four parts: base building, peaking, sharpening, and recovery. Depending on the length of the goal event and how specifically you want to train for it, these blocks can last anywhere from 15 to 26 weeks long.

Base-Building Phase

In the base-building phase of your training block, you build aerobic fitness by running most of your runs at an easy pace. During this time, your muscles grow, you develop more efficient channels for blood flow into those muscles, and your skeleton and soft tissues adapt to the stresses of running. Nearly as important, you establish a positive routine and become accustomed to the sometimes-challenging nature of running.

An average base-building phase lasts eight to 12 weeks, but it could be longer for runners who are training for longer trail races.

Peaking Phase

After base building, you move on to the peaking phase, during which you continue your easy running while adding speedwork and hill workouts that are applicable to the type of event for which you’re training. These workouts build on your aerobic base to make you faster and stronger.

This phase is normally six to 10 weeks long.

Sharpening Phase

Sharpening serves up your body’s final preparations for your goal event. During sharpening, you cut a significant part of your easy running and maintain most of your goal-appropriate speedwork and hill workouts.

Aside from keeping your mind and body sharp, this period allows your body to recover physically from the tolls of hard training. But this period isn’t about rest, because fitness can be lost if you do too much of that for too long.

Sharpening should last from seven days to three weeks.

Recovery Phase

Taking time off after your goal event is often a good idea. Time off can mean 100% rest, cross-training, or disorganized running. You do this to give your mind a break and your body’s various systems a chance to recover fully from the stresses of running.

For shorter goal races, like a 5k or 10k distance, this phase might be a couple of days long, but longer goals like half marathons or marathons may require two to three weeks of recovery.

Paddy O’Leary exhales at the finish line of the 2021 Canyons 100k with a beer. Image: Tony DePascale

Organizing Your Training Schedule

Whether or not you develop a training plan, you should vaguely aim to include an easy run, recovery run, or rest day every other day or at least every third day. After you get into the heart of your training program, your weeks might be a roughly even mix of hard days — long runs, speedwork, or hill workouts — and easier days.

Although the focus here is organizing your running schedule, you can also add in cross-training. Just make sure not to do a hard cross-training workout on a day you are supposed to be recovering from a hard running workout.

You’ll also want to make sure that you don’t increase your training too quickly at any one time. You should follow the 10% rule, meaning that you shouldn’t increase your training volume, measured by either distance or time, by more than 10 percent from week to week.

Your body needs time to adapt, and you may be only a couple of weeks from injury if you increase your training volume too fast.

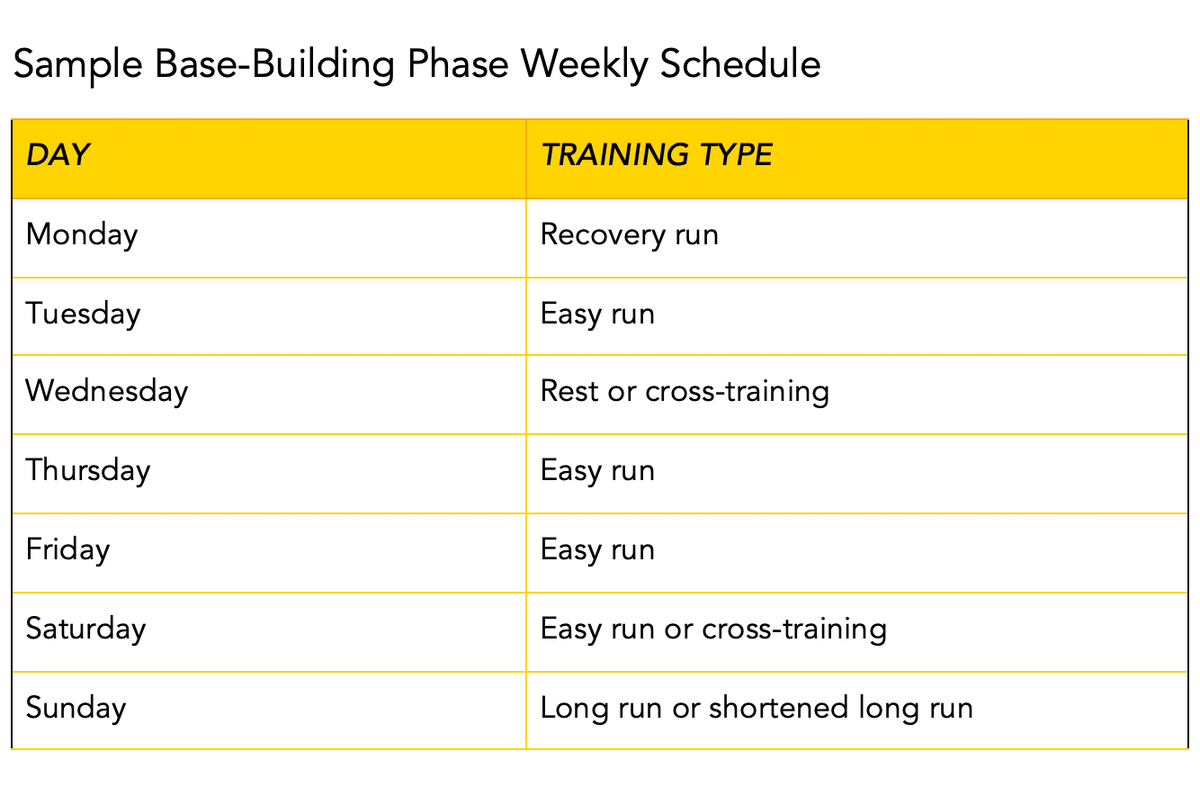

Schedule for the Base-Building Phase

When you are in the base-building phase of your running, your weekly running schedule should be composed of easy runs, one long run or shortened long run, and one recovery run the day after your long run. From time to time, it’s okay to infuse a little extra effort into your running.

But keep in mind that your goal with base building is to create a strong base of aerobic fitness to use in later phases of training. Also, don’t be afraid to replace easy runs, recovery runs, and cross-training with a rest day when you need one.

How a week of training could look in the base building phase of your training plan. Image: Human Kinetics

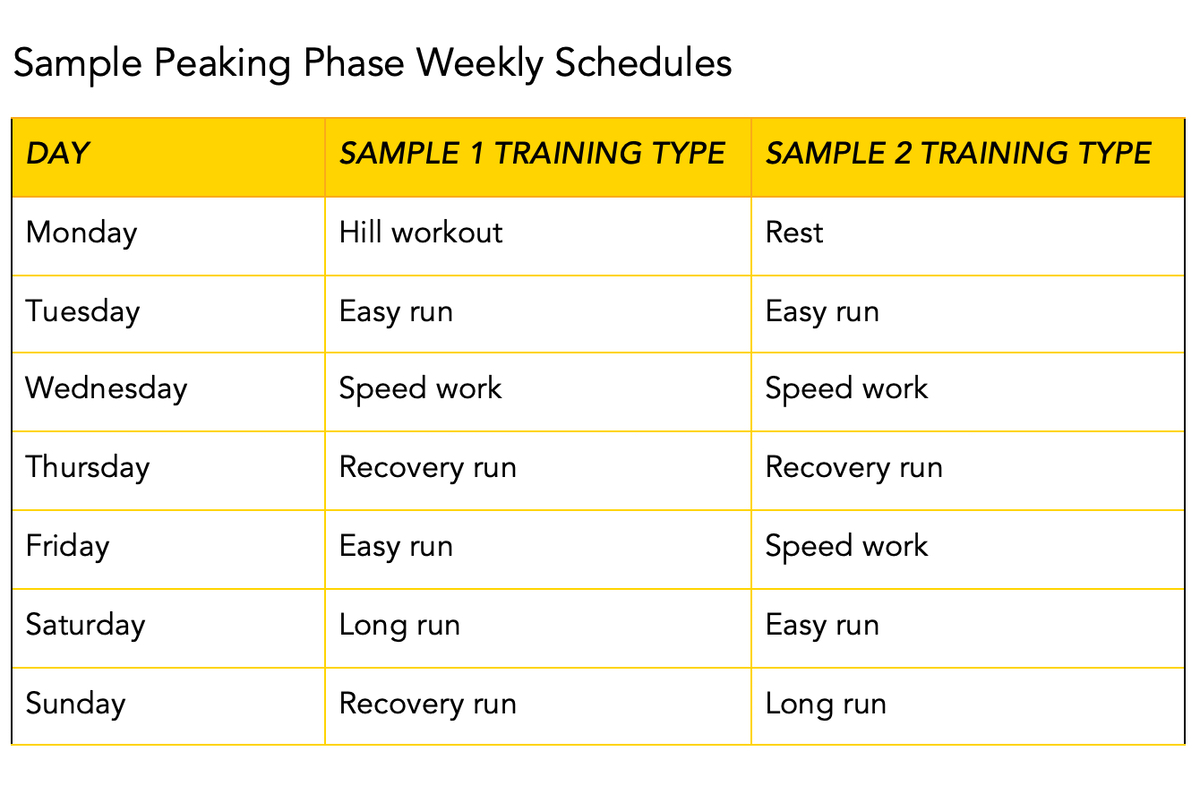

Schedule for the Peaking Phase

In the peaking phase of training, a typical weekly schedule includes the easy, long, and recovery runs of the base-building phase and at least one, maybe two. speedwork sessions or hill workouts added. The most challenging part of designing a weekly plan in your peaking phase is deciding what speedwork and hill workouts you should do.

Especially important for trail running is to practice running fast on the kind of terrain you’ll face in the race. If you are training for a very hilly 10-mile (16-kilometer) trail race, then hill workouts would be of enormous benefit. Still, your body’s aerobic system should be worked at all speeds, so you should cycle in a diversity of speedwork and hill workouts.

As mentioned previously, alternate hard and easy days. Although you must do hard work to grow stronger, it’s during recovery that your body absorbs and incorporates that hard work. We’ll say it again and again: Fear not the rest day!

A couple of examples of how a week of training could look in the peaking phase of your training plan. Image: Human Kinetics

Schedule for the Sharpening Phase

In the sharpening phase, remove much of your easy and long running but keep speedwork and hill workouts in the schedule. The sharpening phase is when it’s most important to tailor your speedwork and hill workouts specifically to your goal race. You can also practice a bit of your high-end running here, such as anaerobic intervals, to help solidify your running economy for game day.

How a week of training could look in the sharpening phase of your training plan. Image: Human Kinetics

Schedule for the Recovery Phase

Take time off after your goal event! This section doesn’t prescribe a recovery schedule, because you shouldn’t have one. Your running should be dictated by how your body is feeling, not by instructions on a piece of paper. Enjoy rest, spontaneity, and moving by feel for a period of time after reaching your goal!

Excerpted from Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running, by Meghan Hicks and Bryon Powell. Human Kinetics © 2016.

Call for Comments

- Do you include all the above elements in your training plan?

- Do you find periodization easier when a coach is involved?