Karma Yangden is a Bhutanese yak herder and cordyceps collector. The former is one of the country’s major domestic animals which produce dairy products, and which are used to transport goods through remote Bhutan. Cordyceps is a medicinal fungus that grows in the Bhutanese highlands and that fetches a large commercial price tag.

The 31-year-old Layup is a mother of three, her oldest two midway through their teens and her youngest a toddler. The Layaps are one of the dozens of indigenous peoples’ groups hailing from the Himalaya of Bhutan.

Karma is also the women’s champion of the 2022 Snowman Race, a five-day, 200-kilometer (125 miles) stage race in northern Bhutan.

Karma didn’t take up running as a kid. Running’s a relatively nascent sport in Bhutan so no one has done that — yet. She picked up running about five years ago when runners turned up in her village, Laya, as part of the then newly minted Royal Highland Festival, a weekend celebration of Bhutan’s diverse highlands peoples.

The 25-kilometer (15 miles) Laya Run takes place as part of this festival and in it participants race from the village of Gasa, located at 2,850 meters (9,350 feet) altitude, to Laya, at 3,820 meters (12,500 feet) altitude.

Karma first ran in the rubber boots many highlands peoples wear to ward off the mud, water, snow, and cold which are replete there. Today, she dresses like any runner you’d see the world over — though she moves faster when she runs than most high altitude mountain running women, and certainly faster than the rest of us ladies who took part in the Snowman Race.

Born, raised, and living an outdoor-based life at high altitude, it’s easy to see why she’s physically good at trail running and ultrarunning — and why she would thrive at a long trail race through her country’s highlands.

The 2022 Snowman Race women’s champion Karma Yangden checks her phone while spinning a prayer wheel. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

But we all know that the best trail runners and ultrarunners have more than just cultivated physical ability. They also possess the psychological ability to adapt quickly to the challenges that arise during laborious runs.

In the West, we use the word “resilience” to describe this character trait. We say that a resilient person is one who can withstand or who bounces back well after encountering a problem.

The term “equanimity” offers an Eastern approach to this capability. For Buddhists, equanimity is a state of calmness no matter what difficulties one experiences.

As I will learn through 2.5 weeks of living, running, traveling, and getting to know her while in Bhutan to participate in the Snowman Race, Karma has had an extraordinarily difficult past. She’s previously been a child wife and a teenage mom, and she is a survivor of domestic abuse. Less than two years ago, the Laya village experienced a climate change disaster, and she lost relatives to it.

I’d venture a guess that most of her adaptability thus comes from her lived experience — and that running is the easy part.

A King’s Crazy Idea

Bhutan is a small South Asian country of about 730,000 people, landlocked between geographic behemoths, China to the north and India to the south.

The Himalaya arcs across the northern half of the country, some of the range’s peaks drawing the border with Tibet. Among this tangle of rock, glaciers, snow, and water, the mountain Gangkhar Puensum, at 7,570 meters (24,840 feet) altitude, rises as Bhutan’s highest feature. In the southern part of the country, the land lowers to about 90 meters (300 feet) above sea level. Remarkably, all of this happens over a small distance, as Bhutan is only about the size of The Netherlands or two New Jerseys combined.

Bhutan is a constitutional monarchy, meaning it has a king, who is the head of state, as well as a voted-in prime minister, who is the head of government. This is the same leadership status as, for example, England or Morocco. While the monarchy part of Bhutan’s leadership is five generations in, the first democratically appointed prime minister was only voted into office in 2008.

The present king is named Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. He’s ruled over the country since his father, the prior king, gave up his throne in 2008. He’ll reign over Bhutan until he says it’s time for him to go, passing the throne to the older of his two sons.

His Majesty The King, as he is referred to by the Bhutanese people, is younger than me and has ruled the country since I was busy doing dumb things in bars as a 20-something-year-old. He and the rest of the royal family are as royal as they get, elevated to the highest level of respect and admiration by the Bhutanese people. It’s the sort of respect for leadership that, as an American late Gen Xer, I’ve not seen afforded to an American leader.

His Majesty The King is an athlete. He’s a hiker, mountain biker, and runner. In 2022, for example — he told us this story himself when we met him after the Snowman Race’s conclusion — he did a half-marathon-distance sightseeing run with a French friend in Paris, France, while traveling to attend the funeral of England’s Queen Elizabeth. This is to say that His Majesty The King can motor.

The 2022 Snowman Race participants on a shakeout run in the days before the race. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Somewhere around 2018, His Majesty The King decided the country should host a race on the Snowman Trek, a remote, long-distance route stretching in an open horseshoe shape roughly east to west through the roadless Himalayan foothills, from outside the city of Paro in the west and the town of Bumthang in the east. The Snowman Trek strings together historic trails set, and still widely used, by highlands peoples to bring supplies via livestock to, from, and between their communities. The entirety of the Snowman Trek is about 350 kilometers (218 miles) in length. Given that they are mostly used by livestock and that they receive little to no maintenance, these trails are little like what Westerners think of as trails. They are braided, have erosion and drainage issues, are really rocky in some places and incredibly muddy in others, and are just plain rugged in comparison to trails of the West.

Along the Snowman Trek, there’s just one reasonable shortcut point, about two-thirds of the way west on the route, where the route passes closest to the village of Gasa. From Gasa to Bumthang on the Snowman Trek is about 203 kilometers (126 miles). Hiking expeditions along the whole route are slotted at about a month long, and treks of the eastern two thirds generally go three weeks in length.

His Majesty The King and the Bhutan government eventually decided that the Snowman Race, as it would be called, should be run on that 200-ish-kilometer distance from Gasa to Bumthang, in a five-day, stage-race format. Participants — around 30, hailing from Bhutan and countries around the world, chosen based on qualifying events and a proven ability to thrive in high altitude backcountry environments — would sleep between each of the five days at backcountry camps established ahead of time by the race organization.

The 2022 Snowman Race’s Night Halt 1, located at about 4,940 meters (16,200 feet) above sea level. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Thing is, such a thing had not been done in Bhutan before — sending out a passel of athletes to cover this long distance over a compressed period of time and through terrain only accessible by foot. In fact, only a few running races of any kind are held in Bhutan each year.

So, the Snowman Race Secretariat was established by the government and populated with everyone relevant to making such a thing happen: the government’s military, geographers, meteorologists, tourism administrators, communications managers, and many others. The secretariat also enlisted the help of American race director, ultrarunner, and all-around good guy Luis Escobar and his merry band of race organizers for the project.

In late 2019, the Snowman Race came to public life, announcing that it would begin on October 13, 2020, on the ninth wedding anniversary of His Majesty The King and Her Majesty The Queen of Bhutan. Then the COVID-19 pandemic stopped the progress of basically everything, shuttering tourism in Bhutan for about 2.5 years and the Snowman Race along with it.

But the Bhutanese are nothing if not resilient — ahem, equanimous — and just as soon as the country reopened for tourism in the fall of 2022, the Snowman Race was set to start on the 11th royal wedding anniversary in October.

When the inaugural event was done and dusted, and we participants were safely back in the capital city of Thimphu, His Majesty The King and Her Majesty The Queen granted to us a Royal Audience. There, Her Majesty The Queen, Jetsun Pema, shared with us that when her husband first told her his idea of the Snowman Race years back, she had thought, Oh, this is another of his crazy ideas.

Her Majesty The Queen is correct, this was a crazy idea.

The Climate Still Changes in a Carbon-Neutral Country

Bhutan is one of the world’s only carbon-neutral countries, in that it offsets at least as much carbon as it uses. If you’ve been working on understanding and reducing your own carbon footprint, then you know that this is an unusual status for a single human being, let alone an entire country.

Bhutan’s carbon neutrality is achieved largely through hydropower, the energy harnessed from several of the country’s biggest river systems cascading out of the Himalaya in the country’s north to its sea-level terrain in the south. The nation’s carbon-neutral status is also achieved because its citizens consume relatively few resources generally.

Pack animals are used throughout rural Bhutan as a means of transporting goods and people. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

All of this said, the critical idea I want to convey is that Bhutan is carbon neutral because it wants to be. The environment is and has for a long time been front and center in government policy, treated at the policy level as equal in value to the health of the Bhutanese people and the country’s economy.

This concept — that the environment and, therefore, the climate crisis, are together a fundamental prong of national policy — is singular in national governments worldwide. There is no other country that has placed the environment, and, these days, the climate crisis, central to its operations. In most countries, capitalism reigns and the economy is valued higher than the natural environment and, if I can be frank, even the health of its human population.

Climate change scientists tell us that climate change more heavily impacts rural communities than people living in cities. There are several reasons for this, but this is strongly a result of how closely rural people live to the land, deriving their food and personal economies from right there. When that land changes, so must the lives of those people.

Most of Bhutan is rural, save for a few dozen square miles around a couple of cities. The climate is changing everywhere in the world, and of course everywhere in Bhutan, yet in Bhutan it’s more prominently felt by its rural communities.

The people who live rurally in Bhutan — that is, the people who have the lowest environmental impact in a climate-neutral country — are among the people feeling the impacts of climate change the most. That is something, isn’t it.

The rural people of Bhutan have been and will continue to be subject to climate-crisis emergencies, like floods, landslides, glacial lake outburst flood events, and other life-altering disasters, in addition to the slow creep of a changing climate and what that means for heating one’s home, watering one’s crops, and caring for one’s livestock.

His Majesty The King established the Snowman Race with the purpose of teaching the world about the heightening climate emergency in Bhutan. Using the Snowman Trek linkup of traditional trails and highlands villages, the Snowman Race would put participants in the literal face of the rising crisis. In fact, the race’s tagline is “The Ultimate Race for Climate Action.”

The idea is that we runners would meet the climate crisis face-to-face, and then bring our experiences back home to share what we saw and learned, with the goal of showing how in a global ecosystem everything is connected, and that even a carbon-neutral country is not exempt from climate change. In fact, more often than not, us Snowman Race participants were referred to as messengers rather than competitors.

The Intimacy of Buddhism

On our first full day in Bhutan — we have arrived about a week before the Snowman Race start in order to acclimatize to the altitude, experience a little of Bhutan’s frontcountry, and organize the logistics of such a remote event — we visit Paro Taktsang, which is better known at least outside of Bhutan by its alternate name of Tiger’s Nest Monastery. If it’s true that first impressions are everything, then Bhutan is hitting the ball out of the park here.

Well, our true first impression of the country was of the sporty Druk Air Airbus landing into the Paro, Bhutan, airport, which is nestled into a valley at times just a half mile wide. That was definitely the first time I’ve looked out the windows of a large commercial airplane to see homes, terraces, and grain paddies at a painfully close distance to a massive metal tube trying to transition from hurtling through the sky at a couple hundred miles per hour to being still on the earth.

But I digress. This incredible monastery clings to a forested cliff high above the Paro Chu valley — “chu” means river or water in Dzongkha, the official language of Bhutan — upstream from the city of Paro.

To visit Paro Taktsang, one hikes about five kilometers (three miles) uphill and climbs about 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) from the trailhead, one way. While these statistics may sound reasonable to the seasoned trail runner, it’s a challenging, full-day adventure for most folks.

Paro Taktsang’s origin story lends itself to its common name. In Tibetan, “taktsang” means tiger’s lair, and one of the monastery’s origin myths is that the eighth century guru Padmasambhava arrived at this location from Tibet riding a tiger and meditated here.

In the 17th century, the first monastery was built at the site. Today, it contains four temples as well as private residences and classrooms for monks and those studying to be one. It’s also a pilgrimage destination for Bhutanese Buddhists and tourists alike.

Paro Taktsang, or Tiger’s Nest Monastery, clings to the cliffs among the clouds. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

While the Bhutanese runners greeted us international runners at the airport when we arrived yesterday evening, and we ate dinner together last night, both were fairly formal, and we were all reserved and quiet. Today’s hike to Paro Taktsang is the first group activity for the Snowman Race’s 29 runners in which we get to informally spend time together.

Most of the Bhutanese runners have been here before, some multiple and a few dozens of times. Of course, it’s a first voyage for all of us international runners. In two large shuttle buses, we carpool to the base of the mountain, and then hike together in small groups to the site.

Vajrayāna Buddhism is the country’s official religion, and Buddhism is integrated into all aspects of Bhutanese society. There’s no separation of church and state — or of spirituality and sports, or of time spent praying and time spent with new friends, in our case.

The Bhutanese runners pray freely as we walk and talk, whispering prayers in one breath and asking get-to-know-you questions in the next. And as we hike, they pause briefly to spin the prayer wheels next to the trail, walk circles around the statues and features inside the temples, and make small cash offerings around the monastery.

While it may not feel this way for the Bhutanese runners, who are, I imagine, carrying on similarly to their daily lives, these hours feel intimate for me. We are invited deep into the halls of one religion’s sacred space, and we bear witness to the way near strangers interact with their spirituality. And for about five minutes inside one of the temples, we sit together, some of us meditating and others of us quietly absorbing the experience.

The effect of the day at Paro Taktsang is powerful, for the way it accelerates the development of our group’s comfort and intimacy. The shuttle bus ride back to the hotel afterward is a lot louder, goofier, and more casual than the one to the trailhead just a few hours ago. First impressions really are everything.

Bhutanese women runners below Paro Taktsang, or Tiger’s Nest Monastery. From left to right are Lhamo, Tashi Chozom, Pema Zam, Vivi Tshering, Kinzang Lhamo, and Karma Yangden. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Snowman Race Day 1: An Auspicious Start

My alarm rings here in Gasa, Bhutan, but I’ve already been awake for a few minutes. My phone screen says it’s 3:30 a.m. on October 13, 2022. The inaugural edition of the Snowman Race begins in a few hours.

For a moment, I lie still. I wonder about the monks a few miles up the hill at Gasa Dzong, a historic fortress that now serves as the religious and administrative epicenter of the Gasa district of Bhutan and where the event will start at 6 a.m., and if they are awake.

A few days ago, Gasa Dzong’s head monk, Tshering Penjor, welcomed the Snowman Race participants and a few of its many organizers into the dzong. Over tea and momos, served to our group of about 40 in one of the dzong’s temples by some of the monks who live, study, and pray there, he said it was his and the monks’ job to ensure the event’s auspicious — a word meaning lucky or fortuitous that is used frequently in Bhutan, and which is probably co-opted into everyday language from Buddhism’s Ashtamangala or eight auspicious symbols — passage through Gasa district.

He explained then that already the monks had begun their prayers for the event, and that they would wake up early on race morning to perform a prayer ritual for us.

A few days before the start of the 2022 Snowman Race, Gasa Dzong’s head monk, Tshering Penjor (center), addresses Bhutanese athlete Vivi Tshering while seven of the nine Bhutanese runners who would participate in the race observe. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Gasa Dzong is perched atop a hillside near the top of Gasa village, its profile dominated by three watchtowers. The dzong was built in the 17th century to help protect the region from invaders from what’s now the Tibetan Autonomous Region, located to the north of Bhutan. Though the region has experienced peace for hundreds of years, maintaining regional safety and function remains a serious matter for the district’s religious and administrative leadership.

When we arrive at Gasa Dzong around 5 a.m., the monks sit with their legs crossed beneath them, in several long rows in a classroom, chanting. We racers are welcomed to watch and listen. Scripture books, one for every two or three monks, sit in front of them, but they seem to chant more from memory than the books.

Young to old, they dress in their traditional red garments, their eyes tilted downward toward the ground, save for stolen glances in our direction, they perhaps as curious about us as we are of them. We would learn later that one of Karma Yangden’s teenage sons — who is studying to be a monk — is in this group praying.

At 6 a.m. sharp, as light begins to flood the inky blue sky of a receding night, and after the most elaborate starting ceremony I’ve yet witnessed in a lifetime of running race starts, a starter’s pistol sends us 29 athletes running toward the highlands.

Before the start of the 2022 Snowman Race, monks pray at Gasa Dzong for the safe passage of the race. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Snowman Race Day 1: She Soars

I’ve reached the finish line of the Snowman Race’s first stage — American Roxy Vogel and I descended from the trail down to our campsite and crossed the line hand-in-hand, the two of us having spent the final 90 minutes of high altitude meandering together.

Most of the 29 of us will make it here, to Night Halt 1, located at about 4,940 meters (16,200 feet) above sea level, though some of us will arrive after dark. Those of us who don’t will be too affected by the altitude to get here, though none of us escape its imposition completely.

Americans Roxy Vogel (left) and Meghan Hicks finish Day 1 of the 2022 Snowman Race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Camp sits amongst hummocky highlands terrain. Mountains immediately to our south rise almost 1,000 more meters (3,280 feet) above us. The scene is figuratively as breathtaking as the altitude is literally so.

Roxy and I promptly begin the chore of putting ourselves back together again so that we can do the same thing tomorrow. We drink recovery drinks, wash our muddy shoes, socks, and legs in a creek, and climb into dry clothes. We’re not in camp for 30 minutes when an avalanche releases from the face of one of the mountains, the snow roaring as it tumbles, cascading out of view behind an enormous lateral moraine.

Moraines are the piles of rocks which are left behind the front and sides of a glacier as it recedes, the detritus of the earth it’s chewed up on its slow march. During the final hour or so of running into camp, we had sneaking glimpses behind the moraine of a turquoise lake and endless piles of rocks. We’ll learn later that this giant moraine once formed one of the boundaries of a glacier which poured itself off those mountains and out into the flatter terrain a kilometer further than it does now. We learn that it is one of many examples we’ll see in the coming days of glacial retreat and an in-our-face lesson of climate change.

A glacial lake in the Bhutanese Himalaya, near Night Halt 1 of the 2022 Snowman Race. As you can see, water is pooling in the moraine, or rocks left by a retreating glacier, to form the lake. If a glacial lake grows too large too fast due to glacial melting, it is at risk of bursting from the moraine and causing a catastrophic flood, what scientists call a glacial lake outburst flood. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

If I can be honest, today is also a lesson in the slowness of forward progress here. We cover something like 46.5 kilometers (29 miles) and gain something like 3,080 meters (10,100 feet). It takes me 9 hours and 41 minutes on the race clock. Our pace is muted by a trio of variables, of course by that altitude, the five-kilogram (11 pounds) pack of mandatory equipment we’re carrying to stay safe, and the mud that is omnipresent when you are below treeline.

Though the going was slow, it was spectacular. From Gasa, we first traveled north, up the Mo Chu valley before turning east into a feeder drainage until we arrived to Roduphu, a small outpost hugging the side of a wide, flat valley composed of a few empty rock huts occasionally used for Bhutanese military patrols, nomadic locals, and Snowman Trek travelers. After Roduphu, the trail hucked itself skyward in the day’s steepest pitch.

All day the weather was moody, offering only caged glances of the high ridges and peaks, with a bit of rain, snow flurries, and graupel. As I climbed out of Roduphu, I looked forward and backward, at the long string of us runners grinding uphill. Among us was one person moving faster than everyone else: Karma Yangden.

Quickly she scampered past me, jumping from rock to rock as we crossed back and forth over a wide stream. It wasn’t long until she and her easily identifiable red hat disappeared over a knoll, and she went on to reach the night halt something like 20 minutes ahead of me.

While we runners are always reaching for our own flow state, the only thing that might be better is seeing another endurance runner in their own. I loved watching Karma soar up here, amongst the rocks and the sky.

Snowman Race Day 2: Where Wild Things Roam

When we are released off the starting line in the pre-dawn of Day 2, we runners slow-motion slingshot toward the sky. Sure, we’re plenty energetic and our eagerness has yet no bounds, but that altitude has a chokehold on all of that, so our pace doesn’t quite match our vitality.

The 2022 Snowman Race participants pose before the start of Day 2 at Night Halt 1 with the camp organizers. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Our first destination for today is Karchung La, one of the major passes we’ll traverse this week. It sits at 5,164 meters (16,940 feet), is blanketed with a thin snow layer, and is adorned with a couple dozen prayer flags.

We are already up high, but Karchung La’s northeast view is of a wall of peaks, which are much higher. This is the second day of my first visit to the Himalaya, and yesterday the high peaks hid shyly in the clouds. This morning’s sky is almost cloudless and this view is insane.

We were told ahead of time that the Bhutanese athletes, the nine of which participating in this race, divided into four women and five men, would likely take a moment to pray at each pass — walking a clockwise circle around the pass’s largest cairn in the same way and for the same purpose that they circumambulate the prayer wheels, temples, and chortens back in civilization, a Buddhist spiritual practice.

We are a train of women when we arrive at Karchung La, a mix of Bhutanese and international participants. I’m not exactly sure what I was expecting but what happens next is entirely unexpected. Any prayers being said by anyone are to oneself as the Bhutanese ladies launch down the pass like little rockets just alighted. This is a race and they mean business.

Australian Nicki Rehn and I are left alone. We snap a quick selfie, squawk about the view, and then drop in and let it rip. The snow on the trail is stomped flat, provides great traction, and squeaks as cold snow does.

Bhutanese runner Lhamo descends from the pass called Karchung La during Day 2 of the 2022 Snowman Race. The altitude here is about 5,060 meters (16,600 feet). Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Something like two thirds of the way down from Karchung La to the river valley far below us, the sun finally reaches us and the trail quickly turns from squeaky to slushy. Nicki, U.S. runner Sarah Keyes, and I come to rest with our eyes on the relatively fresh track of a wild animal through the snow, which fell a couple nights ago. I snap a couple photos.

We’re pretty sure it’s a wild cat track — it looks nearly identical in size and shape to the mountain lion tracks I occasionally see where I live in the Western U.S. Tonight, at Night Halt 2, we’ll confirm with a forestry official there that this is indeed the track of a snow leopard, one of the shyest, rarest, and most endangered wild cats in the world.

A snow leopard print in snow below the pass called Karchung La during the 2022 Snowman Race. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

We are still traveling northeast, as we have been since Roduphu yesterday afternoon during Day 1, and we’ll continue this way until we reach the river valley. That meeting point will be the closest we’ve gotten thus far to the Bhutan-Tibet border, under 11 kilometers (7 miles) as the raven flies from there. And we are in the thick of Jigme Dorji National Park, Bhutan’s second-largest national park, located here in the northern part of the country, and part of the 42% of the country’s area which is federally protected — an insane amount of real estate compared to most other nations’ wildscape preserves — to help conserve wildlife populations like that of the rare snow leopard as well as the agrarian way of life of the rural Bhutanese.

We three continue downhill, continuing what will be a hours-long game of leapfrog well down the river valley, with Sarah first taking point, Nicki on the middle spot, and me the caboose. I can just barely make out Nicki shouting as we bounce amongst the slush, mud, and the views of the biggest mountains I have personally ever seen.

She couldn’t be more precise as she shouts, “This is wild!”

Snowman Race Day 3: What Goes Up Must Come Down

The bigness of Days 1 and 2 were child’s play in comparison to what we will experience on Day 3. Today we will crest the highest point of the race, Gophu La — “la” is pass in Dzongkha, but maybe you’ve sorted that out — at 5,472 meters (17,955 feet) altitude.

It’s not only a lofty destination, but it’s also the most remote part of the Snowman Race course, and it additionally marks the boundary between Jigme Dorji National Park and Wangchuck Centennial National Park, the latter the largest national park of the country. This will be the kind of wild I’ve not experienced before.

But, way bigger than all this, and in order to get from where we are, a village called Lhedi in the Pho Chu valley, to Gophu La in the first place, we must travel through the site of one of Bhutan’s biggest examples of climate change.

Glacial lakes are lakes which form at the base of generally receding and melting glaciers, their melt water bunching up on the moraines left by those retreating glaciers. In these settings, the glacial melt water is held back by rock piles as young as the water itself, not ancient, hard bedrock. Sometimes, too, what scientists call dead ice is in the moraines, glacial remnants that make a moraine impenetrable to glacial lake water.

As the lakes grow, they mostly leak just enough water into the earth and the drainages below them to exist sustainably. Rarely, but with increasing frequency as the climate rapidly warms, they fill until they burst in what’s called a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF).

On October 6 and 7, 1994, the glacial lake Lugge Tscho — “tscho” is lake in Dzongkha — burst, and violently flooded the river valley below it. Twenty-one people up and down the Pho Chu valley died, more were injured, livestock killed, property destroyed, and the whole of the river valley changed form with flood waters heavily eroding some parts of the valley, ripping out thousands of trees and vegetation along with it, and depositing sediment that rendered prior agrarian terrain unusable.

During Day 3 of the 2022 Snowman Race, looking down the Pho Chu valley toward the village of Lhedi in the distant right, miles of boulders fill the valley, which were deposited in the Lugge Tscho glacial lake outburst flood. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

These lakes and their GLOFs have been studied in detail around the world, including in the Himalaya. Scientists have concluded that some of them are the natural outcomes of the retreat of the Little Ice Age, the world’s most recent ice age, and others are the result of climate change. The Lugge Tscho GLOF was an effect of climate change.

For more than 16 kilometers (10 miles) on the morning of Day 3, we travel up the valley containing Pho Chu and see how the valley was changed by the Lugge Tscho GLOF. In doing so, I fall into a lady gang. There are five of us women running and powerhiking in lockstep, Bhutanese runners Lhamo and Kinzang Lhamo, Americans Roxy Vogel and Emily Keddie, and myself.

Lhamo and Kinzang essentially take turns pacesetting, and us Americans fall mostly into line behind them. We are working together, chatting a bunch, and overall friendly as all heck, but there is some gaming happening too.

The Bhutanese ladies are moving conservatively, more so than I’ve seen them move all week, clearly not wanting to work too hard so early in this really hard day. And Roxy, Emily, and I are a little antsy — and naïve, in my case — making small breaks here and there to move a little harder. But Lhamo and Kinzang cover each move, and we end up close together for all of these first 10 miles.

During Day 3 of the 2022 Snowman Race, runners approach the village of Tschojong. From left to right are Kinzang Lhamo, Emily Keddie, Lhamo, and Roxy Vogel. On the right of the photo, severe river bank erosion due to the Lugge Tscho glacial lake outburst flood is visible. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Soon we are at the edge of a village called Tschojong, which appropriately translates from Dzongkha as valley of the lake. We’re just a few kilometers downstream from Lugge Tscho and at least three other lakes which have names on the map and which scientists say are high risk lakes for GLOFs.

Locals have come out to watch our progress, two elders offering us yak cheese and slices of apples for our journey — way up here above treeline and in such a remote spot, these offerings are of high value. Domestic yaks bathe in the river and graze. The sun has risen above the mountain tops, melting frost off the tundra and lifting our spirits toward the line of glacier-covered peaks to our north, some of them 7,080 meters (23,250 feet) tall. We women race together in a friendly competitorship — always kind but always pushing to rise us all higher. The scene is, for me, as idyllic as one could imagine a race through the Bhutanese Himalaya to be.

But we know all is not entirely well in this valley, and soon we are running atop more evidence of its sordid past. A several-kilometer long set of sand dunes deposited here by the Lugge Tscho GLOF is one of the multiple physical reminders of the flood in this valley.

A view looking up the valley from the village of Tschojong during the 2022 Snowman Race. Evidence of the Lugge Tscho glacial lake outburst flood can be seen via river bank erosion and large sand dunes in the distance. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

We make our way up the valley, through one more settlement, and across the impressive Pho Chu on an equally impressive metal suspension bridge. I reflect on how this river must have raged during that GLOF.

It is thus with some solemnity that we begin a big climb up one of the valley’s shoulders toward Gophu La. I try my best to sear these moments into memory, so that I can share this story with you. But to be frank, there is no trying, a little piece of my heart stays in the valley bottom, even as our bodies rise higher.

Our ladies’ enchainment eventually thins out, as we find our own paces in the equally thinning air. For me that means coming to a brief halt with my heiney on the tundra to eat a Snickers bar; I’m on the edge of bonking and we’ve got a long way to go, so it’s time to take in a lot more calories.

If snarfing a Snickers is a typical ultrarunner scene, then so is the puke-and-rally that follows. We’ve ticked past the 5,000-meter (16,400 feet) mark, and I guess my body is telling me that it’s time for liquid calories only.

After what seems like a very long time, I finally crest Gophu La. It’s more like the highest hill of a massive plateau than a steep headwall, and waiting here is a member of the Bhutanese army, one of a several dozen of these folks who are assigned to help keep us safe this week.

I snap a couple photos, listen to him radio my bib number into the Snowman Secretariat base which is monitoring the race’s progress all week back in the city of Thimphu, take in the long light of the afternoon, and feel overcome by a sense of euphoria.

A view looking backward on the 2022 Snowman Race course from near the race’s high point, a pass called Gophu La, which is 5,472 meters (17,955 feet) tall. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

I am well fueled and my body feels good, I’ve now passed all the members of this morning’s lady gang, and I’ve even come up close behind the first and second place women for today, Karma Yangden and Tashi Chozom, the latter of whom is the fourth Bhutanese woman in the race.

Along with the joy comes a small sense of smugness. I think, With a little oomph I’ll catch the women in front of me and we’ll be into the night halt by sunset.

This is well and truly a case of famous last words because soon the course markings become sparse so I begin navigating by the Gaia app on my phone, which requires slower movement. Next a fog comes up the valley and envelops everything more than 100 feet away, preventing me from using any long-view landmarks to navigate, slowing things some more. Then night follows, which means one’s worldview is limited to the glow of your headlamp. And finally, the campsite is nowhere to be seen at the GPS point we’ve been given for it.

The next several hours are a hectic scene. First, Lhamo comes up behind me and we pair up to work together. Next, we sweep up Tashi who is coming backward on the course, convinced that we’ve missed the camp in the fog and night. Then, the three of us are swept up by all the runners behind us, who’d also packed up into a couple groups to work together, as well as a couple members of the military who’ve decided we could use a little assistance in finding camp.

In fairness, we had been told that navigation, rather than simply following course markings, would be required during the race. However, up until Gophu La, the markings were so good I’m not sure I’d needed to navigate yet. Also, the race organization had told us that Night Halt 3 was further downstream from the GPS point we were given for it, as bad weather had damaged the planned campsite location. We were told to just keep going on the route until we got to camp. What we runners did not know was that the night halt was more than five kilometers (three miles) further. So when almost everything was obscured by fog and darkness, and we kept going without seeing any sign of camp for miles, it was easy to think we’d missed it.

Once we arrive to camp safely as a huge group, and I lay my bruised ego and self down for a few hours of shuteye, I muse on how the highest highs seem to precede the lowest lows, and vice versa — in ultrarunning, in life, and I guess in climate change too.

The view from near the pass called Gophu La on the 2022 Snowman Race course, located at 5,472 meters (17,955 feet) altitude. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Snowman Race Day 4: Better Together

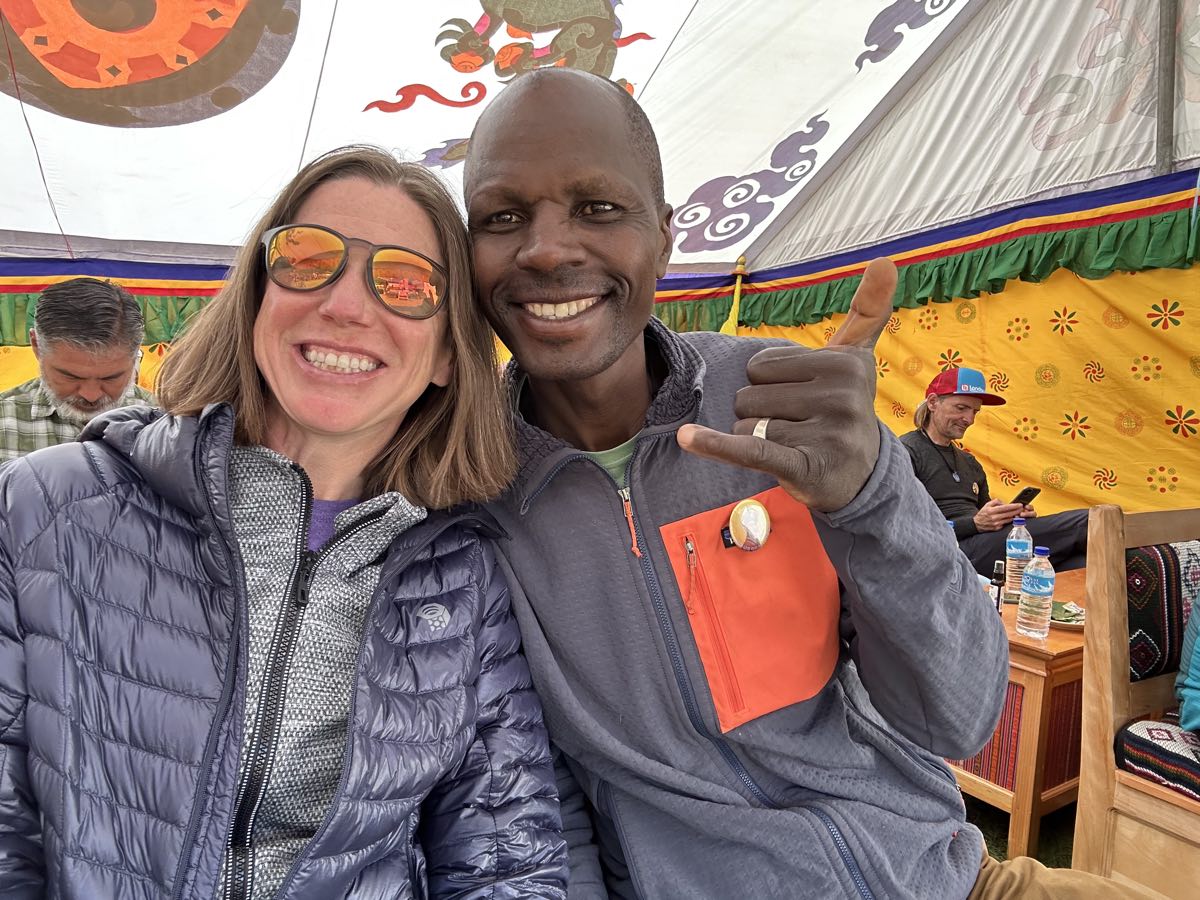

I’ve known fellow Snowman Race participant Simon Mtuy, a Tanzanian runner, family man, mountain guide, and farmer, for some 15 years. I met him in the summer of the late two thousand aughts, he holed up in the higher reaches of California’s Sierra Nevada, training for the revered Western States 100, where I was working and living at the time. Our friendship has endured since then.

I speak the tiniest bits of Simon’s first language, Kiswahili, courtesy of a couple college courses, a semester abroad in Tanzania, and some visits since then to East Africa. Simon’s always been willing to humor me and my horrible butcherings of his language.

That includes this moment, as we are making our way up the final climb of Day 4. “Pole pole ndio mwendo,” is a Kiswahili proverb literally translating to, “slowly slowly is the way,” and figuratively meaning that a measured approach is the best one.

Simon and I have leapfrogged each other all day, and in doing so we’ve whispered these words to each other each time we pass, peppering in some hoots and hollers of louder encouragement when we’ve accordioned out but the bends in the trail and breaks in the terrain allow us to glimpse one another.

It is often said that running is a fairly solitary endeavor. Unlike some sports which are built upon a team foundation, the vast majority of adults who run are not members of a running team. While running as a general sport may trend toward the solitary, ultrarunning is the niche corner of the sport where the help of others is essentially a requisite of our movement toward the finish line. An ultrarunner travels so far and for so long that they often cannot do so without the aid of someone, somewhere — and sometimes quite a lot of it.

Maybe this is a reason some of us have an ultrarunning bent, that we have some not fully understood desire to share the experience with something beyond the inside of our own skulls? This is at least the case for me on this mountainside today.

A view during Day 4 of the 2022 Snowman Race, looking down at the lake called Julay Tscho from the pass named Gongte La. At the far side of the lake is Night Halt 4, where runners would sleep after the fourth day of running. The lake’s altitude is 4,330 meters (14,200 feet). Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

I would also argue that working together is always better. You can always do more with others than you can do alone. Simon and I, we are both working pretty hard, and we are a bit tired on this fourth day at high altitude and after many kilometers covered, but his words of encouragement amplify my movement. We cross the finish line a minute or so apart, I most certainly having gotten there faster because of him.

Fast forward several days into the future, once the Snowman Race is over, to where Simon shares with me a bag of coffee he’s farmed to enjoy back home. The bag of coffee bears his company’s name: Umoja.

This is a Kiswahili word I immediately recognize, and which couldn’t have a more appropriate meaning for our hike up that mountainside, our collective participation in this race, and our world’s necessary work on the problem of climate change.

“Umoja” means together, because of course it does.

The 2022 Snowman Race participants Simon Mtuy (right) and Meghan Hicks after the event’s completion. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Snowman Race Day 5: The Day the Whole Nation Ran with Us

While it might be a little easier to make it on the national news in a country of less than a million people, and there is also the fact that the Snowman Race was ideated by His Majesty The King of Bhutan himself, it becomes immediately clear during the final miles of Day 5, as we come off the remote Snowman Trek route and make our way along dirt and paved roads to the Snowman Race’s finish line in the center of the town of Bumthang, that everyone out here knows something of what we’ve been doing back there.

First, there is an increased military presence, it seems like there are army men every couple kilometers to ask us how we’re doing and radio in our race number to base.

Next it’s the schools, probably around six of them along the route to the finish line. At each one, all of the kids wait for us to pass, holding signs they’ve made containing messages about the environment and cheering.

After that it’s the national volunteer group in Bhutan called the Desuups, something like the U.S.’s long gone Civilian Conservation Corps. In their neon orange outfits they line the route, offering water and juice.

And finally there is the stadium finish line, filled with what has to be 1,000 people. I can count on one hand the number of ultrarunning races I’ve been to with more than 1,000 fans at the finish line, yet here, in little Bhutan, they gather.

Ahead of me at the finish line by plenty of real estate is Karma Yangden, who wins the women’s race, clear of the rest of the field by a cumulative two hours over five days of racing. Behind her are Kinzang Lhamo and Lhamo who take second and third. In the men’s race, Gawa Zangpo of Bhutan earns the men’s crown.

By the time I cross the finish line I feel like the whole nation has run with us this week. It makes me feel like this sport of traveling around in the mountains is more than just sating my wandering fever. That doing this, that being in this moment, that carrying those stories from all the way out there to you reading along here, matters — at least a little.

The 2022 Snowman Race champions Karma Yangden (left) and Gawa Zangpo (right) with race director Luis Escobar. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

To Hold Hope Lightly

In the early morning hours of June 16, 2021, heavy rains fell over a large swath of Bhutan and neighboring countries, triggering several flash floods and landslides in both Bhutan and Nepal, destroying property and stealing lives.

In the mountains above the Bhutanese village of Laya, home to 2022 Snowman Race women’s champion Karma Yangden, a landslide broke loose and tore through a campsite filled with sleeping cordyceps collectors. Ten Layaps were killed, five were injured, and a bunch of the collected cordyceps was washed away.

Among the deceased were four of Karma’s relatives.

It was the worst tragedy in remembered Laya history, but not the worst tragedy induced by a changing climate in Bhutanese history. It’s just one amongst a growing collection of stories, several of which we saw the effects of during the Snowman Race.

It’s terrifically ironic that the 2022 Snowman Race, an event with the tagline “The Ultimate Race for Climate Action,” women’s champion is a survivor herself of a climate change disaster.

What now? This is the thought which has kept me awake at night in the time that’s passed since the race finished.

What do we do with what we know about Karma and the way climate change is threatening her village’s well-being? Of bearing witness to the signs and symptoms of the retreat of glaciers’ effect on the landscape of Bhutan? Of seeing villages of people whose lives changed once because of the climate crisis and whose lives will probably change again?

What actions do we Snowman Race participants take using the knowledge we’ve learned? And should we, can we have hope for a different future?

Punakha Dzong, one of Bhutan’s emblematic structures, is located about 90 kilometers (56 miles) downstream in the Pho Chu valley of Lugge Tscho, the glacial lake which burst in a catastrophic flood in 1994, causing loss of life and property throughout the valley. Punakha Dzong experienced minor damage in that flood. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Westerners have an odd relationship with hope — I’m saying this as a Westerner with that relationship myself.

“I hope it’s warm next week for our party!”

“I hope I have this baby soon!”

“I hope we can slow the climate crisis.”

In those statements are wishes about things we cannot control: the weather, when a woman’s body decides a baby is fully baked, and if the leaders of powerful companies and nations, as well as billions of individual humans, will decide to reduce their environmental impacts.

Buddhism, I’ve learned, prefers a more ethereal relationship with hope.

A portrait of Bhutanese runner Kinzang Lhamo who took second at the 2022 Snowman Race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

American Sharon Salzberg, author, Buddhist, and teacher of meditation and other Eastern practices, wrote, “The hope resides in the certainty of relief not in specific outcomes, like getting exactly what we want; the hope comes from the way things actually are in this universe: This too shall pass.”

This does not mean that Buddhists don’t have hope, Sharon Salzberg says, rather that they endeavor to hold hope lightly. That is, it is not that they live in the absence of hope, but rather they live with an acceptance that our individual desires cannot infer large-scale outcome.

Running experts tell us this very same thing, that we should attach ourselves to the processes, but not the outcomes, of our running.

“I hope I get on the podium at this weekend’s race,” is a statement which hinges a working definition of success on the uncontrollable variables of the others who enter the race and how fast they run.

“I’d like to run within 10% of my PR on this course,” is thus a more process-oriented approach to our running, setting the standard for success in circumstances over which we can control, like our speed, pacing, and strategy.

The idea of a light, Buddhist, process-centric approach to hope can also be found in an untitled poem of prized American poet Emily Dickenson. Here’s the first stanza:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers —

That perches in the soul —

And sings the tune without the words —

And never stops — at all —

Dickenson’s version of hope is, metaphorically, an unceasingly vocal song bird.

And perhaps literally, this hope is the notion of looking forward and moving onward that exists inside of us, because — and maybe in spite — of the human condition.

It’s this precise kind of hope, the ability of resiliency or equanimity, the action of proceeding lightly no matter what is happening around us, that I think I saw in the Bhutanese people in general, and in people like Karma Yangden specifically.

Dickenson’s poem has two more stanzas:

And sweetest — in the Gale — is heard —

And sore must be the storm —

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm —

I’ve heard it in the chillest land —

And on the strangest Sea —

Yet — never — in Extremity,

It asked a crumb — of me.

I learned so much during my weeks in Bhutan, but the most important thing that I learned is this: we all must, figuratively, sing.

His and Her Majesties The King and The Queen of Bhutan, the Snowman Race Secretariat, and the dozens of people who made this logistically improbable event happen for the purpose of conveying a message about climate change to the world, they sing. Karma Yangden and the other Bhutanese runners who live amidst a storm of global climate change swirling around them, they sing, too.

And so here I am, singing, holding onto hope just as lightly as my Western-raised brain can tolerate.

Karchung La is a pass sitting at 5,164 meters (16,940 feet) altitude in the Bhutanese Himalaya. The 2022 Snowman Race crossed Karchung La on Day 2. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Thank You

“Kadrin chhe la,” thank you in Dzongkha, to all the people and entities who enabled my participation in the Snowman Race, and those from whom I’ve learned along the way.

Kadrin chhe la to His Majesty The King and Her Majesty The Queen of Bhutan; the Snowman Race Secretariat; Luis Escobar, Thomas Reiss, and the rest of the Snowman Race organization; and the 28 other athletes with whom we shared this experience.

Thank you explicitly to Snowman Race Secretariat members Sonam Euden and Sonam Rinchen, who enriched my experience in Bhutan.

And namey samey kadrin chhe la to Karma Yangden for allowing me to learn and share a small part of your story.

All of the 2022 Snowman Race participants and some of the event organizers below Paro Taktsang, or Tiger’s Nest Monastery. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

References

- https://www.adb.org/features/bhutan-s-hydropower-sector-12-things-know

- https://toolkit.climate.gov/regions/southeast/rural-impacts#:~:text=Rural%20communities%20have%20long%20made%20their%20livelihoods%20from%20farming%20and,inher

- https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap9_FINAL.pdfently%20vulnerable%20to%20climate%20change.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paro_Taktsang

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38048989.pdf

- https://www.gasa.gov.bt/gewogs/lunan

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Region-of-study-Lugge-Tsho-was-the-source-of-the-1994-GLOF-event-while-Raphstreng-Tsho_fig1_344302893

- https://www.alliedacademies.org/articles/tsho-glacial-lake-outburst-flood-glof-in-bhutan-cause-and-impact.pdf

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/3673897?origin=crossref

- https://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=151711

- https://onbeing.org/blog/sharon-salzberg-how-to-hold-hope-lightly/

- https://www.edickinson.org/editions/4/image_sets/80358