[Editor’s Note: The following piece is an excerpt from the book “The Examined Run“ by iRunFar columnist Sabrina Little, which launches on March 1, 2024. Congratulations to Sabrina! If you enjoy the essays she shares here on iRunFar in her column of the same name, we hope you’ll consider supporting her by purchasing “The Examined Run.”]

I once had a middle school athlete run a personal best in the mile by 60 seconds in one race. This is a massive margin of improvement in a marathon, let alone a mile. And he improved because I told him before the race to pay attention. Previously, he never focused. I am not sure where, mentally, he would go.

I wager it’s the same place many of us go when we get lost in our own heads at various moments of racing and training. It is probably the same place where our missing socks are — somewhere in the abyss. Regardless, this time he focused, and he saw a massive improvement as a result. He drew closer to his potential than he ever had in the past.

Sometimes improvement is that simple — paying attention. But, for many of us, it is not. For many of us, we have to go to difficult places when we race, squeezing out every bit of ourselves to improve by narrow margins.

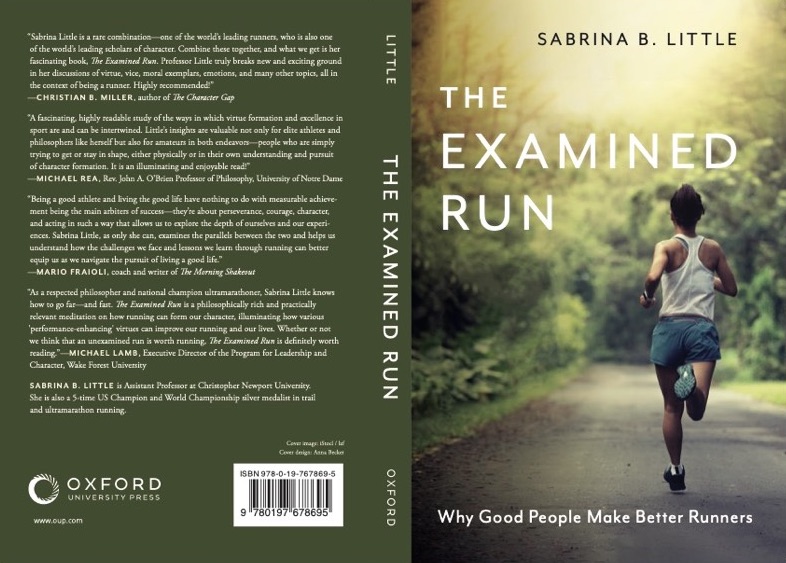

Sabrina Little with a copy of her new book, “The Examined Run.” All photos courtesy of Sabrina Little.

It is an uncomfortable process, one in which you negotiate with yourself to draw closer to your limits, inching toward your body’s distress signals. It feels like you are blindly navigating through your own suffering — gritting your teeth, feeling your way toward your limits, and hoping you don’t push yourself further than what you can take.

I wish I could claim that you will know when you cross the line into unproductive strain. But if there is one thing I have learned through my own suffering, and the suffering of the young athletes I have coached, it is often difficult to locate this line.

It is difficult to know whether a discomfort is edifying — the fruits of a constructive athletic practice — or the beginnings of an injury. It is challenging to recognize where our limits actually lie.

The Paradox of the Heap

There are extreme efforts and obvious instances of overstepping limits; these are easy to detect. Examples include increasing mileage abruptly or attempting massive efforts an athlete is unprepared for. But often our mistakes are gradual — like an athletic sorites paradox (the paradox of the heap).

Every crumb of difficulty we add to our training load is like an additional grain of sand, and it is unclear at what point the grains form a heap.

Sometimes we straddle unsustainability and lean too far in the wrong direction. Sometimes we cannot discern whether we are making a Faustian bargain or are just getting the most out of ourselves in a reasonable way. Sometimes we only know this in retrospect, after stepping too far.

This is especially so since, as fitness waxes and wanes, the locations of our physical limits shift. An athlete’s breaking point is not something one can learn once and then assume it will remain the same thereafter. It changes, even over the course of a single season.

Productive Versus Unproductive Suffering

Young athletes especially struggle to know the difference between productive and unproductive forms of suffering. They tend to err in one of two directions: Some find all discomforts alarming and want to back off. They may lack an appetite for arduous goods and choose to be comfortable instead. Otherwise, they might think suffering, in itself, is a problem. These athletes often train only up to the point of difficulty. Then they slow down.

Other runners have the opposite issue. They fail to back off when they should and either overcook themselves like cafeteria ziti, or they end up injured. For this second group of runners, it can be confusing to know whether backing off from a workout is prudence or laziness, so they choose neither.

It is important to coach these athletes differently, pressing the risk-averse to make peace with difficulty, and encouraging the tough ones to self-assess and speak up about discomforts. Returning to the “warped board” imagery from Chapter 2, we can coach the athlete toward virtue by pulling them in the opposite direction of their natural warp, to incline them closer to the mean.

Furthermore, it can help athletes to look to an exemplar — what Aristotle calls the phronimos, or the person marked by practical wisdom — for guidance on how to suffer excellently. Often professional runners serve this role, but tread carefully. Elite-level athletes are (of course) elite. Their abilities typically far exceed our own, and their incentive structures are different.

Sometimes taking cues from elite and professional runners about stress and rest is not helpful for the non-elite runner. The time and resources professional runners devote to recovery impact how well they can absorb the suffering they endure in the sport, and they often have teams of people helping them monitor progress and regress in training.

It can be helpful for nonelite runners to look to other runners similarly positioned to themselves instead — athletes with school or jobs, families, and other hindrances to rest — for guidance in how to draw lines regarding their elective suffering in the sport.

Call for Comments

- Do you embrace suffering in your training or do you struggle to push yourself?

- Do you think you are good at measuring your effort, so that suffering stays productive?