[Editor’s Note: It’s with great sadness that we note that Earl Blewett lost his battle with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, in June of 2022. His presence in American trail running and ultrarunning as an athlete and race director are missed.]

Stories of runners getting lost during ultrarunning are rare, but not unheard of. Sometimes the runner simply takes a wrong turn and gets back on the course, but other times, the searches are a bit more involved. Such was the case with Earl Blewett.

As iRunFar previously reported, Blewett, of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was in the midst of the 2021 Ancient Oaks 100 Mile when he vanished around mile 55 and over 14 hours into the event. As a 57-year-old ultramarathon veteran of over 90 races, the majority of them ultras, Blewett didn’t seem to be having any trouble prior to his disappearance, which took place on Saturday and Sunday, December 18 and 19, 2021.

But the Ancient Oaks course, run on a 3.4-mile meandering loop, ran through dense foliage in Titusville, Florida, with other trails not included in the race crossing the course multiple times. Additionally, it was somewhere after 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, and dark, when he went missing.

After a search that lasted 36 anxious hours over two nights and a day, and included a helicopter, four-wheelers, dogs, and volunteer groups, Blewett was found, disoriented and injured, but ultimately all right.

We wanted to talk to Blewett about his experience, and find out what really happened on those days. But the truth is, because Blewett fell and hit his head, we may never know exactly what happened, because Earl doesn’t remember a lot of it. What he does remember is falling and hitting his head, turning his ankle quite badly, and lying in the woods for a long, long time.

The scenery at the 2021 Ancient Oaks 100 Mile where Earl Blewett went missing for about 36 hours. Photo: Matt Mahoney

Mike Melton, the race director, said that up until 4:30 p.m. on Saturday, Blewett was doing fine, though he had warned him that he becomes disoriented and turned around at night.

“When he came through the start-finish area again around 9:30 p.m., he had gotten turned around [leaving the aid station] and we had to point him the other direction. He said he had somehow hit his head on a sign, but that he was fine. We assumed he would come back through around 11:00 to 11:30 p.m. … When he didn’t, we started looking: calling his phone, his emergency contact, looking for his car … sending people out to run the course,” said Melton.

During Melton’s long tenure as a race director of over 300 ultras, he said people often leave the course to take naps in their car, go lie down somewhere, and don’t check in. But this was the first time someone wasn’t found after calling around and a bit of searching.

Blewett doesn’t remember everything that happened, but he thinks what set off his path of misadventure was his ankle.

“So, I turned my ankle during the race,” said Blewett. “It was really bad. That’s why I couldn’t move, and I wasn’t actually wandering around the woods [when I was missing. The majority of the time] I didn’t go anywhere. I was laying in the same spot for over 24 hours. I put my ankle up on a log and kept it there.”

While this might seem implausible considering the robust search effort that took place, the foliage surrounding the course is extremely thick in some places, and even a single large saw palmetto plant can easily hide an entire human laid low in the preserve.

A severe concussion, which Blewett may have well sustained, can cause post-traumatic amnesia, including delusions and hallucinations, which Blewett began to experience in the dark.

“I was laying there and I thought I was at my hotel. I was absolutely sure that I had driven back to my hotel, and I had laid down on the bed. I had a flashlight with me so I thought that was a light switch, and there were so many plants around, I figured this must be some sort of eco-lodge … which is funny because I was in the woods surrounded by trees.”

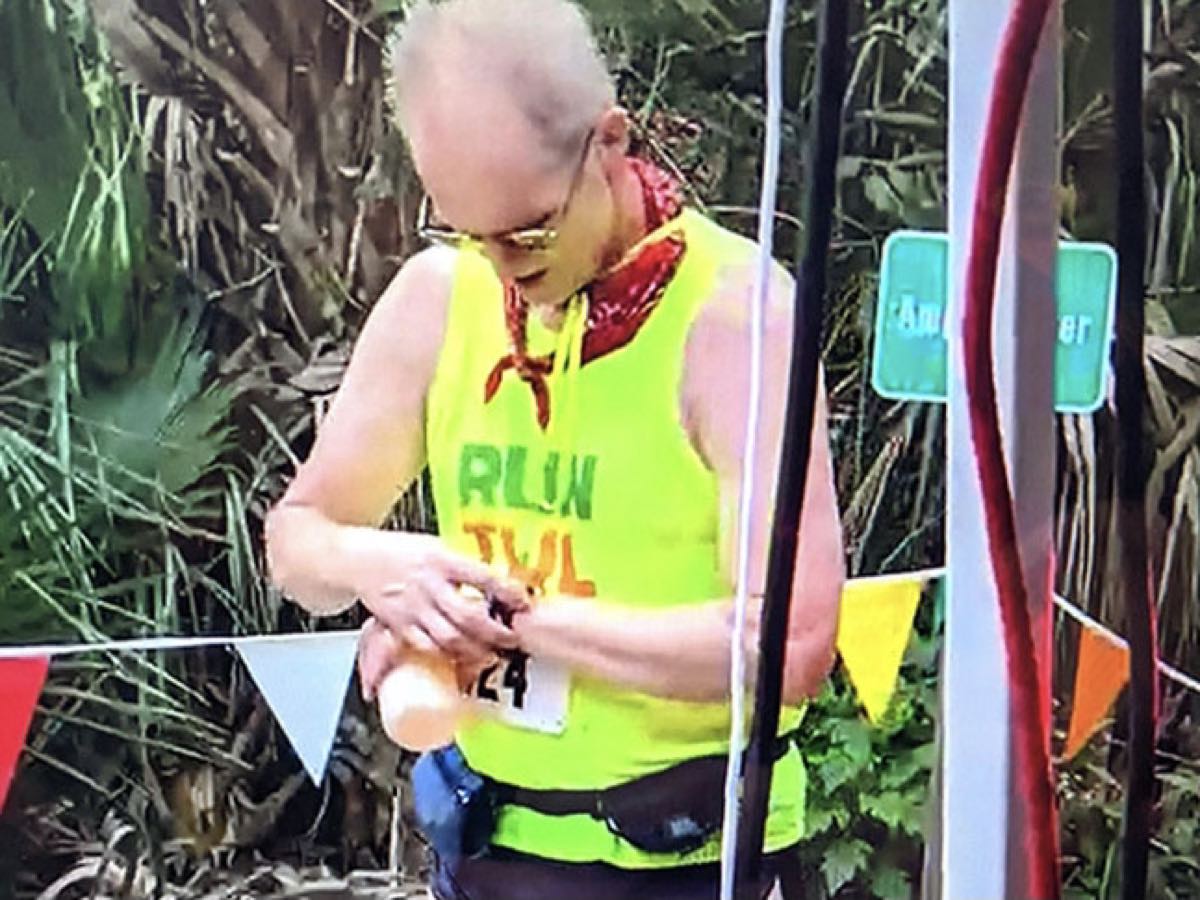

Earl Blewett at the 2021 Ancient Oaks 100 Mile before going missing. Photo courtesy of the Titusville Police Department.

Blewett is no stranger to ultras: he’s been running them for over 25 years. He said he normally goes out with a map or Garmin watch, but didn’t see the need on a 3.4-mile non-mountainous loop course. However, even if he had brought a map, with the symptoms he was having, it’s unlikely it would have helped him.

So there he was, concussed, dehydrated, tired, and in the dark. Blewett had his single water bottle with him, but doesn’t remember consuming any food during the 36-hour ordeal. He lay somewhere in the woods throughout the night and next day, through the rain, shivering all night long.

Blewett said he remembers he had thought maybe he would pick up a pacer to go through the night with, but he never crossed that checkpoint once it was dark. When he hadn’t been seen on the course, the search began: helicopters picked up no heat signal of his body, dogs couldn’t trace his scent, and volunteers didn’t find him anywhere in the woods.

Detective Shawntrale Durden, one of the lead investigators on the case from the Titusville Police Department, explained why the dogs might not have been able to pick up on Blewett’s scent.

“We use a few different kinds of dogs: bloodhounds, cadaver dogs. They were tracing his scent to a swampy area. [Blewett] recalled that he had fallen into water at one point, so it’s likely he fell in this water, and then left the area. The dogs traced his scent to this area then the trail went cold, probably because his scent would have been washed off.”

Blewett’s wife, Jen Kisamore, was back at home in Oklahoma, figuring out how to get down to Florida, potentially with their daughter and dogs in tow.

“I got a call saying Earl was missing,” said Kisamore. “They thought he might have driven off because he was disoriented … but then they found his car. So the police called me saying a search was on … I was freaked out by Sunday when they hadn’t found him. I packed as much as I could and [on Monday] was ready to drive down there.”

The search-and-rescue when it was in progress for missing ultrarunner Earl Blewett in Florida. Photo: Matt Mahoney

Prior to the police starting their investigation, Melton and race volunteers had covered the entire course and surrounding area as extensively as they could: sending runners both forward and backward on the course, as well as on surrounding roadways and ditches.

On Monday morning, just shy of 36 hours after he was last seen during the race, Kisamore got a call from Durden, who Kisamore said seemed like she was nearly in tears, saying they’d found him. He’d somehow managed to make his way across a four-lane highway and into a secure manufacturing area, and talked to a man parked in a car, who recognized him as the missing runner from the news.

“The detective was so excited,” said Kisamore. “She thought [that by that time] it was going to be a body recovery.”

Durden confirmed it was a very emotional time for everyone.

“When you have something like this, when a person goes missing for so many hours, even though he’s in good shape and good health, you get really worried. Of course, after the first six to eight hours we assumed the worst, because that’s what we see in our line of work. You start to lose hope.”

Thankfully that wasn’t the case, but Blewett was in bad shape. He was taken to Parrish Medical Center in Titusville to be evaluated, and ended up staying nine days. Blewett described the extent of his injuries.

“Well, when they admitted me to the hospital, I had this great big wound on the back of my head … cuts and scrapes all over … and thousands of bug bites. My ankle wasn’t broken but because I had put it up on that log so long, I had a compression injury, like in diabetics, on the back of my calf.

“I got rhabdomyolysis from laying in the same position so long, so my kidneys shut down. They were only at six percent function [in the hospital]. The first thing they did was a CT scan of my head, and they said there was no bleeding in the brain.”

[Editor’s Note: Rhabdomyolysis is a condition where muscles are damaged to the extent that they release proteins into the bloodstream, which eventually reach the kidneys, causing a toxic shutdown. It usually occurs from over-exercise coupled with dehydration, but can be caused by a fall and compression — lying in one spot too long.]

Earl Blewett’s knee with his ankle raised to decrease swelling, showing the bug bites covering his body. Photo: Earl Blewett

Melton was incredibly happy that Blewett was found and all right. “I was just thinking he had a heart attack, or a stroke, or something. I just can’t figure out how he crossed that road. It’s a four-lane highway with a 55-mile-per-hour speed limit.”

Blewett can’t figure it out either, because he can’t remember. Thankfully, he was released and is now recovering at home. Blewett and Kisamore said they are eternally grateful to everyone who helped with the search effort, and that everyone — the race volunteers, police, doctors, and nurses — were “so kind.”

When asked what he plans to do next, Blewett replied, “Well, I’ve already pulled out of one race because I can’t walk right now because of how badly I turned my ankle … I’ve promised I’ll buy a Spot tracker.”

On the upside of this whole ordeal, Blewett managed to connect with many friends and relatives he hasn’t talked to in years, inquiring after his well-being, one of whom toasted him, “May your successes be as spectacular as your failures!”