“We need to see our story continuing, not that we’ve reached the final page of our book and have nowhere to go.” — Steve Magness

I’ve survived the rooty, rocky, wet-in-parts descent. I briefly reflect that a combination of adrenaline and the supernatural levels of concentration one can bring to bear when racing have helped deliver me safely to the bottom of the slope. Arriving here in one piece gives me a surge of satisfaction and confidence.

On the rising traverse that follows, I’m feeling good, despite the heat of the day pushing down on us all. Neither the heat nor the altitude bothers me. I can tell others are not so fortunate. Slowing leg speeds and heavy breathing are all around and I’m easing past other runners. When the gradient kicks up at the start of the climb to La Flégère, it’s time to welcome in the pain and work harder. I haul harder on my poles and ask my legs for more speed.

As I pop out of the forested section, the heat increases. The chairlift looms over me like some weird skeletal creature. Over the years in other races, this open-piste section has been purgatorial. Today, it’s not and I try to up my speed further and pass as many of my fellow runners as I can.

The truth is, I never thought I would be here again, racing.

In mid-July 2016, I awoke in a hospital bed after a running accident, left leg encased in plaster from big toe to groin, to be told by a senior consultant surgeon that I had so damaged my left knee that I would never run again. A couple of days later, after scans, he repaired my left knee over four hours of surgery.

As it turned out, that prognosis wasn’t accurate. I won’t dwell on the recovery save to say it was long (almost three years), arduous, involved quite a few tears, required the help of outstanding surgeons and physiotherapists, and most importantly, the help and support of my family, my wife, Alison, in particular. I’m eternally grateful to them.

Parts of me are not as nature intended. Each of my anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament was repaired with hamstring tendon grafts, my medial and lateral menisci were repaired, and my cartilage (not damaged in the fall but showing signs of significant wear after 30 years of high activity) was repaired as a bonus item.

My tibia, splintered in the accident, was plated and secured with eight screws, aided by a bone graft taken from my left hip bone. Seven months later, a smashed collar bone, which had no chance to fix itself having had to bear weight from the day after the surgery, was plated with the help of 10 screws.

My left knee no longer flexes normally. This gives all sorts of complications. Running downhill is uncomfortable and often hurts. It is mechanically problematic and mentally challenging; the accident occurred running downhill and my central governor can take over. Spin classes, hydro-jog and aqua-aerobics classes, gym classes, and the bike are all part of my life now. But running in the mountains, they are not.

I took my first tentative running steps in the third year of recovery. But it was only in mid-2020 that I woke up one morning and wanted to go running — four years after the accident. The speed of physical and mental recovery from major trauma can be very different. After a period of trying to restore some semblance of fitness, I returned to some competitive running during 2021.

A self-imposed rule means I don’t contemplate running any further than a half marathon. I avoid road running. I finished three trail half marathons in the year, in times between 2 hours and 37 minutes and 2 hours and 20 minutes. Three runs a week is the most the joint can safely handle, and 20 miles in a single week would be very much the upper limit for training. I tread a fine line. I try to focus on uphill and flat running where there is room for improvement. My next significant birthday starts with six, and my aim is to stop getting slower. For me, 13.1 miles is the new 100 miles.

In June 2022, Alison had her 60th birthday. She had designs on winning her new age category in the Marathon du Mont Blanc. With forward planning, we configure four weeks away, initially with our various children and their partners, followed by a block of time for her to prepare to race at the end of the four weeks.

Post-COVID-19 lottery hangovers from previous years deliver a one-in-seven chance, and she fails to get a place. Some rushing around secures her a charity place in the 23-kilometer Cross du Mont Blanc, the original Chamonix trail race, this year in its 43rd edition. She will run for a local charity, which raises funds to support children’s sporting activity in the Chamonix valley.

Somewhere along the line, as the “Cross” is badged at 23k, which isn’t much more than my half marathon limit, and is largely uphill, I convinced myself that attempting to finish the race is an achievable goal, and I breeze through the one-in-two-chance lottery.

A few days before we travel, midway through a 12-mile trail event, I develop a sudden pain around my lower ACL attachment in my bad knee. It wants to give way on me, but some bad language and bloody-mindedness get me to the finish. But there’s no time to seek help before we travel.

Race preparation is hindered by the ACL problem, which means that I can’t run downhill on steep terrain, a problem in the Alps around Chamonix. In the three weeks before the Cross, I run perhaps five times only. On the plus side, it’s boiling hot with daytime temperatures in the low 30s Celsius. We hike a lot, I have time to refresh and perfect my pole technique, we get up to 2,700 meters a couple of times, and we have lots of time to look over the course.

We last raced the Cross about 15 years ago and there have been some course changes; an extra climb out of Argentière to Le Planet and the challenging descent mentioned earlier. I run the race route from Chamonix to Montroc as a long run and have visions of my time estimate of between four and 4.5 hours proving distinctly inadequate. How will the post-accident body and mind handle an extra two hours of effort? Alison is in better order and gets in some good preparation.

The day before the Cross there is a significant afternoon storm, which causes the cancellation of the 90k race. Later in the evening, the skies clear and the forecast for race day is for good weather and is slightly cooler than the late temperature peak of 28 degrees C.

The start is in four waves of around 500 runners each. It’s the usual febrile congregation of Lycra. Ludo, the master of ceremonies, is whipping up the enthusiasm level. I’m alone as Alison is in the wave ahead of me. I have some trepidation as to what might lie ahead and seek some relative calm from Ludo’s verbal frenzy at the back of the pen. I do my best to empty my head. I’ve been here before many times, almost in this exact spot when lining up for the Cross, Marathon, Vertical Kilometer, and 90k event, as well as CCC, UTMB, and Trail des Aiguilles Rouges.

It’s different this time. I’ve been granted a second running life. It’s another of my rules that I try very hard not to look back on races, runs, and times before the accident, not to make comparisons of then with now, not to wish I had completed such and such a race. I fear that way lies a dark night of the soul.

Buddhists maintain that craving is the root of suffering and that comparison is the thief of joy. I’ve been prepared to accept those philosophies. Yet, sifting through the memories of so many experiences in these mountains, mostly good ones, reminds me that I have done hard things here before, and that counts for something. This place and these mountains have given me so much over 30 years and neither owes me anything. I count my blessings, not the least of which is making it to this start line.

Away we go. A few minutes from the start in the Bois du Bouchet, the heavy morning dew and the rain in the trees capture and magnify the low, early-morning sun into a hazy, golden aura. The sight is breathtaking and as I’m at the back of wave two, and barely into my running, I have time to marvel at the light show.

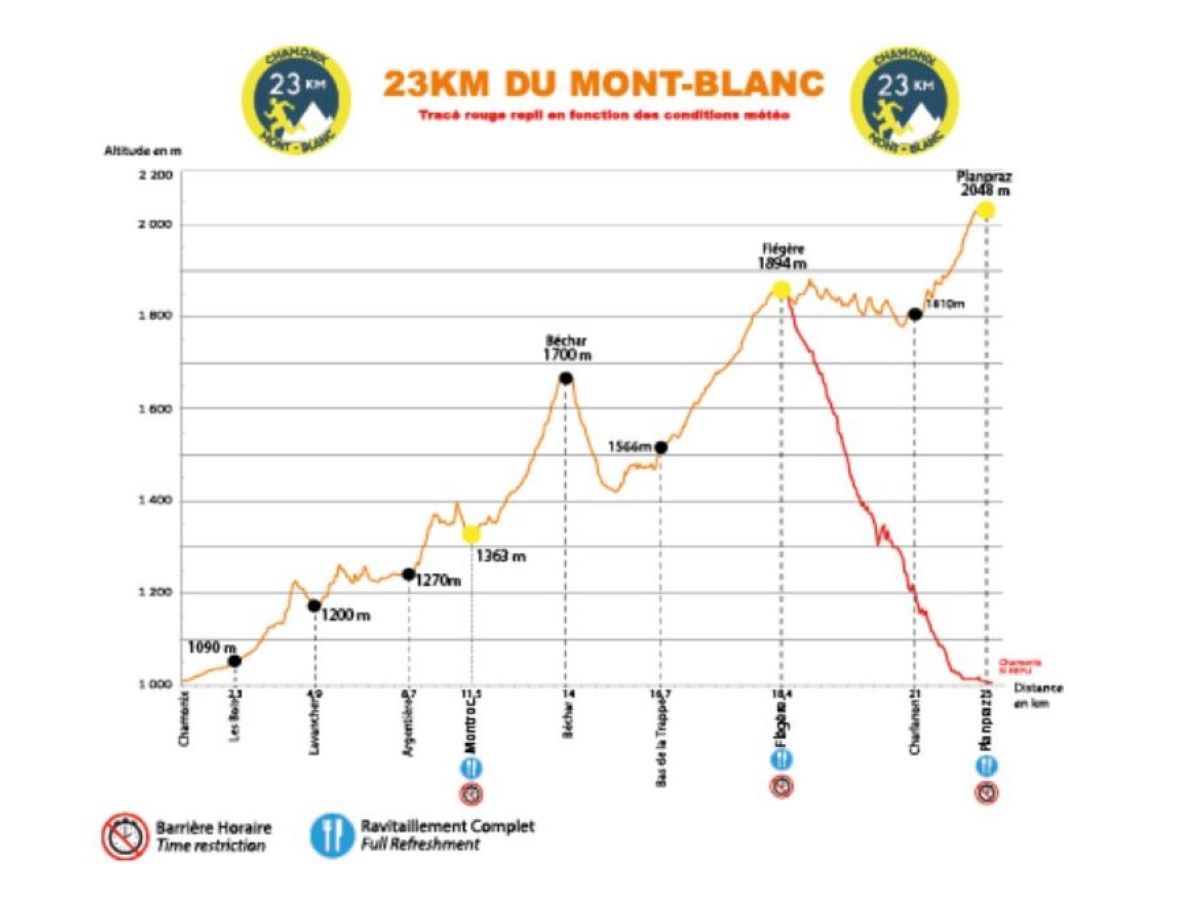

For once in my running life, I have a race plan. Looking at the race profile, it is easy to construct and understand. It is essential that I arrive at Montroc (11.5k) in good shape to be able to get to the finish. I want to arrive there no earlier than 1 hour and 40 minutes elapsed from the start. After that, I need to survive the descent from Le Béchar to Bas de la Trappe. Then, try and press on to the finish at Plan Praz. There is more hope than expectation in the final part of the plan.

As I make my way up the valley, the faster runners from wave three catch and pass me. As they zoom by, occasionally on narrow trails, I try to ignore them. My equanimity holds, and I don’t allow this procession either to annoy me or to undermine my effort to reach Montroc in good order.

Perhaps, I think, I might see some of you later. I’m somehow disconnected yet also fully present and focused on my task. Kilian Jornet described something similar recently: “Cheering and noise on the ears and silence in the head.”

I am through the aid station at Montroc in less than a minute, grab a piece of local cheese and a slice of cake on my way out, and head off eating at a fast walk. The trail to Le Béchar is steep and narrow in parts, which means the initial effort and forward progress are limited both by the gradient and by the press of humanity. The left turn arrives, and the descent begins. Which is where I began this story.

It is hot on the final part of the climb to La Flégère, but I’m passing plenty of runners. For the second time, I’m in and out of an aid station very quickly. More fluid, more cheese, more cake. I wonder, vaguely, how Alison is getting along in front of me. What remains now is the 5.3k to the finish at Plan Praz, with a further 311 meters of elevation gain. I’ve been back and forth across this traverse many times over the years, including walking it as part of our preparations this year. I’m not foot-perfect, but I’m on very familiar ground.

The traverse passes in something of a blur as I pursue and then pass more runners. It’s hard work but not impossibly so. The closer to Plan Praz I get, the more people are out trailside supporting the runners and their cheering for me makes me wind up the effort even more. I’m running sections that I would normally hike.

Then after a short downhill and a cheeky upswing to the finish, I’m across the line and done. I forget to press stop on my stopwatch but know that the LiveTrail tracking gadget will tell all in due course.

After finding Alison (who has been told she is the first woman over 60, but who must wait until all four waves are finished), I guzzle a goblet of Bière du Mont Blanc, and have a lie-down on the Plan Praz grass. It might take a while to process the last few hours. For both of us.

A short while later her win is confirmed. She moved into first place with a fast aid station transit at La Flégère and then held the lead to win by just 24 seconds.

It’s only later after digesting my LiveTrail data that it all sinks in. 24.4 kilometers, 1,656 meters of climb, a time of 4:26:40. Time to Montroc, 1 hour and 42 minutes. (Hah, the plan worked!) Race rank 1,594 at the first time check at Le Lavancher. Race rank at the finish, 947, top half! 647 places gained! That’s crazy.

Kilian Jornet has a saying: “My big moment is always tomorrow.” As a guiding philosophy for running and indeed life, it’s hard to fault. The 2022 Cross is as close as I’m going to get to fulfilling those words. I can’t imagine that I could have a better day.

Then it’s time to drive home. Chamonix has been its usual exciting and dramatic self. But the deep satisfaction that I feel with my effort and our mutual delight at Alison’s win is tempered with deep concern and perhaps sadness as we leave.

On June 18, during our time in the valley, a record temperature of 10.4 degrees C is recorded close to the summit of Mont Blanc at 4,750 meters. The previous record was 6.8 degrees. The blazing hot weather has triggered significant rockfall in the mountains, and the Guides Office is publishing daily updates about the mountains, which are in a highly dangerous state.

Just after we arrive home, a chunk of the Marmolada Glacier in the Dolomites unexpectedly collapses and kills seven people. Not long after that, the voie normale on Mont Blanc is closed along with the Goûter and Tête Rousse huts along the route. The crossing of the Grand Couloir, long dangerous, is now a death trap. The Guides Office strongly advises that certain sectors of the range are unsuitable for mountain activities and are in essence, out of bounds.

In September, horrendous data is published showing that Swiss glaciers have lost 6% of their remaining ice volume in the last year.

It feels like the world is catching fire and the mountains are collapsing. And that perhaps this piece should have been titled One Last Time.

I then stumble across the reaction of the writer Alex Roddie when he returned to the snout of the Arolla Glacier, eight years after his previous visit, to discover “no ice.” His feelings of extreme disorientation strike a chord with me. He tries to order his thoughts and reactions and is patently struggling with his emotions and fears for the future. A few days later, he has refined his reaction and it is brutal. “The birthplace of adventure itself is mortal. I have seen it turning to dust.”

It is hard to be anything other than a hypocrite with regard to climate change, its causes, and the efforts to mitigate it. Giving far greater thought to the scope, scale, and frequency of all of our activities, especially those in the mountains, is now critical. For, as Roddie notes, time is very short.

Call for Comments

- Have you had a second chance in your running life like the one the author describes? Tell us your story!

- Have you been to Chamonix? Have you noticed the glaciers getting smaller or other evidence of climate change in the mountains?