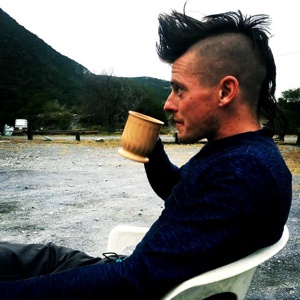

Max Romey has seen some plastic waste in his day.

Since first moving to Alaska as a teenager, the artist and filmmaker has witnessed a dramatic upswing in plastic waste of all varieties — even in the massive state’s remotest reaches.

Alaska holds more coastline than the rest of the continental United States combined, and recent trips to help with clean-up efforts in places as far-flung as Katmai National Park gave Romey a sense of urgency. The heavy incidence of shoes made a special impression on the 29-year-old.

“There can be a lot of trash out there. Suddenly you’ll run into 30 shampoo bottles in 100 feet or a huge Goodyear tire, and you’re walking on microplastics you can’t see,” Romey said. “And worn-out shoes are everywhere — still out there making literal footprints. That’s where the perception shifted for me.”

What could he do if he focused on those footprints, which the trashed shoes were making all by themselves, he wondered.

Romey got out his sketchbook and camera and started documenting his findings. It led to a film project which he hopes can motivate people to be more planet-friendly with their disposal choices, and a collaboration with Kilian Jornet’s NNormal.

NNormal’s recently announced No Trace Program is ambitious: Send in any pair of athletic or hiking shoes in any condition, and NNormal will either upcycle or recycle them. The same goes for clothing, from pullovers to race vests to running shorts.

Romey’s documentary, “No Lost Shoes,” premiered on February 13 in support of the program’s launch.

It’s hard to say which aspects of the Anchorage, Alaska, resident’s personality play up more through the film: his upbeat, inquisitive attitude or his passion for Alaskan conservation efforts. After 15 years of life experience covering a lot of ground in the vast state, he’s seen pollution start to overwhelm landscapes he remembers as fully wild.

“At first, I saw this amazing, wild place that just seemed untouched. Then I saw the scope and scale of the plastics that are here — and then I learned how microplastics can inject themselves into this ecosystem,” he said. “The scale of this place is huge, but it is so connected.”

Romey gave the scientifically supported example that microplastics can make their way up the food chain from the bottom. The smallest microplastic particles can appear in zooplankton. Bigger organisms like marine invertebrates and fish can consume them from there, and so on. Alaska’s salmon population creates particularly high concern because they spend part of their lives in freshwater and part in saltwater.

On top of that, wayward trash tends to collect in Alaska due to the way Pacific Ocean currents move around its coastline. In fact, prevailing currents create a gyre, or circular system rotating around a single point, in the Gulf of Alaska off the state’s crescent-shaped south coast. This stark National Public Radio article shows the mounting scale of the problem — as it existed back in 2015.

“In the winter, a lot of the storms we’re having right now, all this plastic floating in the ocean gets thrown up on these beaches and just strained out. And so when you can actually get there in the summer, you have these totally wild places — I mean, it looks like ‘Jurassic Park’ mixed with ‘Lord of Rings’ times a whole bunch of bears,” Romey joked. “But then you’ll come up on all this trash, and it suddenly looks like some industrial park in L.A. The contrast is real.”

In the documentary, Romey works with the Ocean Plastics Recovery Project in an effort to investigate the problem and solutions to it. Specifically, they focus on our global shoe problem.

Yes, global. The film points out that we manufacture an estimated 20 billion pairs of shoes each year. Getting rid of them has proved challenging. That’s where NNormal comes in.

What the company proposes to do is re-stream any still-usable parts of the shoes (or other donated clothing) that it can. From there, Romey described the sorting method as a sieve. A NNormal representative confirmed that the next tier consists of the company recycling any parts and pieces that it can. And everything else can become materials used in items like mattresses or synthetic turf.

NNormal hopes the pieces of the donated items that are solid enough to reuse can help pay for the rest of the program. A partner in the U.S. and one in Europe will help the company pull off what could be a massive effort, depending on how it catches on.

That’s another thing “No Lost Shoes” seeks to help with. Romey said he’d like the documentary to inspire people to act. Or even to take urgent action. The more time a piece of plastic spends in the natural environment, the filmmaker pointed out, the less possible it becomes to simply pick up and properly dispose of.

“It’s like a slow-motion oil spill,” he said. “Any plastic polymer will never break down. It will only break up into smaller and smaller pieces, and if you don’t catch it before then, you’ve missed your shot. So that’s why it’s really important to have end-of-life options for anything that uses plastics or rubbers.”

You can watch “No Lost Shoes” in full today. To take part in NNormal’s No Trace program, go to the newly formed shoe company’s website and follow the step-by-step process.

As Romey pointed out, you can’t drain the tub just by unplugging the drain — you also have to turn off the tap. His focus now is to lay a viable foundation for his three-month-old son to build on.

“The last four years, I’ve traveled all around the world to make these cool films about athletes doing awesome things — and a lot of it was to sell shoes,” he said. “Now, I’m thinking about what the repercussions of that are. I’m waiting to find one of my own old pairs of shoes out on a beach somewhere.

“I’ve seen some changes, but the scarier thing for me is, what are the changes we will see [in the future]? In the world my son grows up in, he’s going to see a dramatic change. I’m hoping that change is going to be a really positive one — he’s either going to be part of the generation that sees this collapse or be part of the reason it doesn’t.”

Call for Comments

- What do you do with your old running shoes once they are worn out?

- Would you be interested in taking part in the No Trace Program?