Joe Grant set a new unsupported fastest known time on the Nolan’s 14 line in Colorado’s Sawatch Range on June 27 through 29, 2018. His time of 49 hours and 38 minutes improved upon the previous unsupported FKT by Andrew Hamilton of 53:39, set in 2015.

The Nolan’s 14 line is a link-up of 14 mountains more than 14,000 feet in elevation. Runners can connect the summits by whatever routes they choose, but routes usually add up to about 100 miles in length, about 44,000 feet of climbing, and about half off trail.

In this phone interview about five days after his finish, Joe talks about what the Nolan’s 14 line means to him, why he chose this venue for pushing his boundaries, the gear and food he chose for his unsupported attempt, and more.

iRunFar: Congrats! Wow!

Joe Grant: Thanks! It was a good experience for sure.

iRunFar: I was honestly surprised when you said you were going to do the Nolan’s 14 line because in my head I was like, Well, he’s already seen them all in his epic bike-hike month of traveling to and climbing all of Colorado’s 14ers. What made you decide to single out these 14 mountains?

Grant: It’s a different experience in the sense that I was out there for a month on the 14ers, so while I had very low moments and it was a deeply transformative experience, this is more the ‘tip of the spear’ condensed couple of days. You’re really immersed in your head and utilizing all the skills that you’ve learned over the years. It feels like a nice way to do it.

I figured I’d probably put myself in a situation where I’d learn something. There would be some growth associated with being able to manage yourself when you’re kind of losing it and not having anyone to bounce ideas off of to get you back on track. There was that curiosity that was interesting to me.

It’s a super beautiful mountain range, too. The Sawatch is really compelling, and there’s the lore of Nolan’s 14 much like the Bob Graham Round. It’s got this identity in the ultrarunning community and I like that aspect of it.

It’s just short enough where I think you can kind of pull it off in this style. Much longer and you need a little bivy system and a bigger pack. I felt like this was the perfect window to experiment and see how I fare.

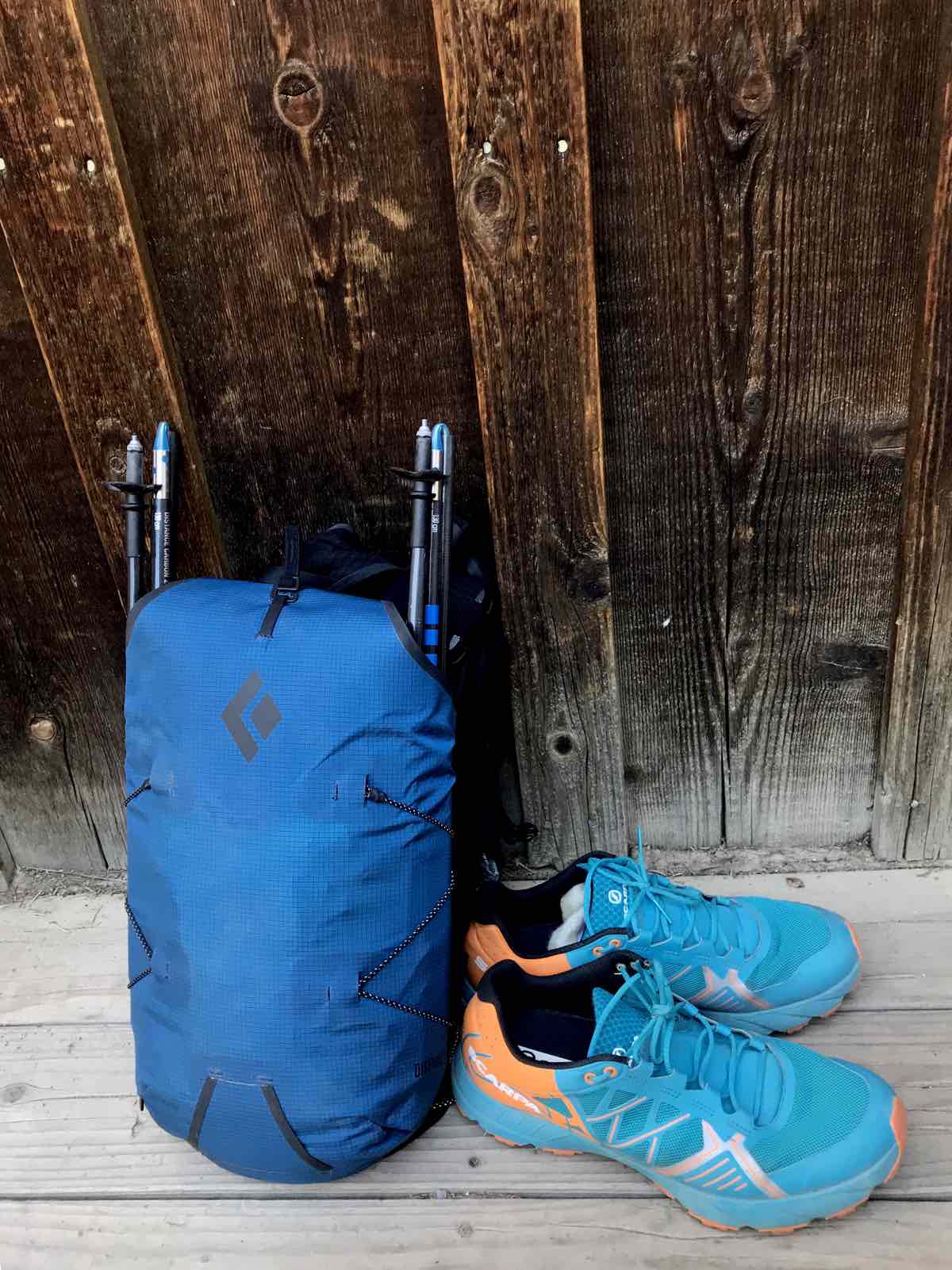

iRunFar: Let’s talk about that unsupported part. When you said you were going to do it unsupported, I thought, Of course he is! That’s Joe Grant style. When it came to the mechanics, how did you manage to keep your pack light? I can imagine for this distance and time, keeping your kit light is tricky.

Grant: If you think about it, it’s like the ‘required gear’ at races. It’s a version of that. Gear is so light now, I had a pair of five-ounce puffy pants, a three-ounce down vest, and a rain jacket. Then I brought a three-ounce windbreaker jacket in my back pocket for day use and you can combine it with the rain jacket and the down vest to make a decently warm combo. The worst I would probably get weather-wise would be a two-to-three-hour downpour kind of thing. That was the main reason for wanting to carry the rain jacket, but it ended up being quite nice for added warmth. It’s stuff that I have used a lot whether it’s bikepacking or doing the 14ers or general mountain missions in the winter. Even in the White Mountains [in Alaska], I’m really confident with that set-up.

Then I brought a mini-emergency kit. Really all that was was a few strips of tape, a knife, a lighter, and a space blanket. If shit really hit the fan, I could get in the space blanket, make a little fire, and I’ve got tape to patch up the bones if they’re broken—hopefully not.

I brought a pair of running gloves and a Merino hat because at night up at 14,000 feet, there were a couple times where it was really blowing and cold. It was so cold that I wore my pants going up and over [Mount] Antero. I was happy to have the gloves and hat there.

I decided to go for a regular Black Diamond Spot Headlamp which is 300 lumens. It’s not the brightest lamp, but it’s bright enough. Combined with the full moon, it was really nice. It’s super light. Then I brought a smaller version of that, the SpotLite, which takes two AAAs, as a back-up.

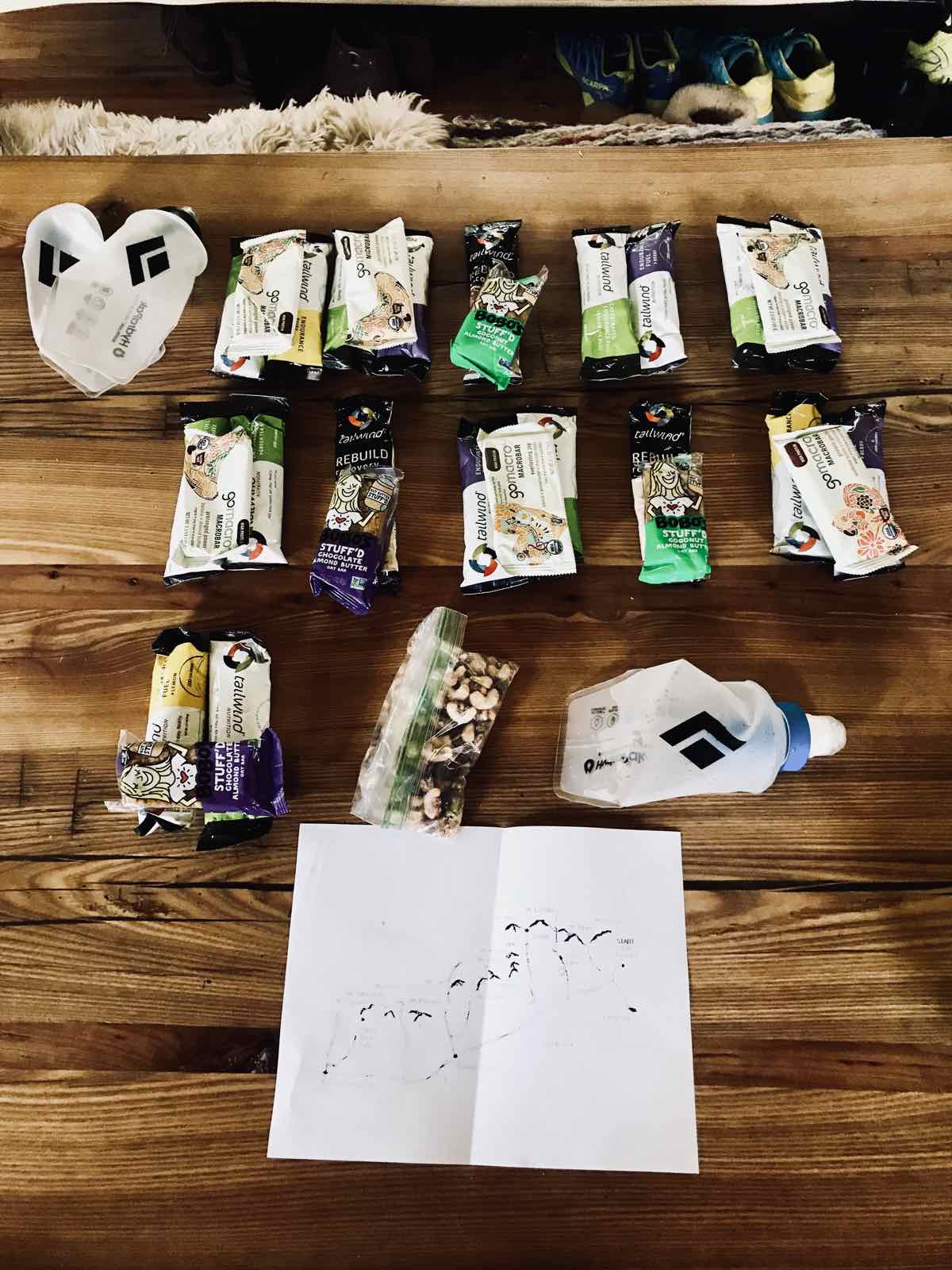

Food, I approached it similar to what I would do at the Hardrock 100. Usually I organize food in terms of time. Oh, I have a three-hour section here, and I’ll bring this much Tailwind and a bar. This time, I organized my food by peak, I’ll do two sticks of Tailwind single-serve packets for [Mount] Massive and one bar. The way I was thinking about it was, I’ll leave the trailhead and get up and over Massive, and once I get down toward [Mount] Elbert, I know there’s a little spring there that I’m going to stop at and fill the Tailwind. Then I’ll have a bar and drink water there while I’m having that bar. Then at La Plata [Peak,] I’ll repeat that process. It ended up being a total of 7,000 calories.

iRunFar: Seven thousand calories for two days, basically?

Grant: Yeah, I think it was about 3,000 calories per day of Tailwind powder, and then I did 10 bars—four of these Bobo’s Bars and six GoMacro Bars—and then a little bag of 1,000 calories of trail mix. That was it.

iRunFar: That’s not much food. It’s a lot of powder calories but not much solid food.

Grant: Oh, and I did bring three packets of recovery protein, Tailwind Rebuild.

The reason for bringing powder is because you don’t carry the water weight, so it’s lighter for the calorie content than solid food. But in retrospect, one of the issues I was having above 13k was getting a little bit nauseous. It wasn’t specific necessarily to the food, but it was super, super hot during the day, and you’re just high for prolonged periods. It was a little bit harder to eat when I was that high. My system was that slow-drip system where you’re gradually drinking the Tailwind over the course of going over the peak.

I talked to Alex Nichols briefly when we saw each other and he mentioned he switched his strategy where he’d eat more down low and then just push over the peak with water and maybe a little bit of something and then eat more down low. That totally makes sense to me but I didn’t have that luxury because I had only 10 bars and it’s not like you’re going to drink a whole bottle of Tailwind. It works better as a slow drip.

I responded really well to the [Tailwind Rebuild]. I thought it tasted really good. I was pretty satiated. The protein, just moving at that pace, was easy to absorb and satiating. That’s something I could have done more in the valleys. When I did, I’d be so psyched. Oh, this is great. That’s maybe the small variation I’d do, bring more of that.

It’s a tricky game in terms of how much to bring because you have to carry it. The more food you bring, the heavier it is, and the more effort it is to lug it up the hill, so you eat more. It’s a tricky balance. I actually finished with six sticks of Tailwind left, so I probably had 6,000 calories for the whole thing.

iRunFar: Let me ask you about the record itself. Did you go into the event with Andrew Hamilton’s southbound splits and the idea that if it’s going well, you hoped you could beat these? Or were you more open and organic about timing?

Grant: I certainly was aware of the records as I follow this stuff pretty closely. But the time for me really serves more as a framework to push yourself. Andrew being the first person to really do it in that style, I’m just following in his footsteps…

iRunFar: All of which is cool…

Grant: Yeah, but he’s the one who set that standard. Following means you have a reference of knowing it’s humanly possible to do it that quick. In practice, I was curious as to how I would respond to that kind of effort and having to deal with everything by myself. I could certainly do Nolan’s at a more casual pace, but I wouldn’t have the kind of experience I was looking for which was a bit deeper and introspective thing. I find that time is a good framework to be able to dig deeper into that place. Once I set off, the actual numbers are sort of irrelevant. It’s more of like, Okay, great. Let’s just go as hard as you can and see how close I can come to that, but even more, how deep I can get into my head by pushing myself.

iRunFar: I thought one of the really interesting things about Andrew’s [unsupported] splits is that he didn’t slow down as much as people tend to slow down in Nolan’s. I wondered if that’s because he’s just so strong or if there’s something unique about the unsupported thing and your pack getting so much lighter as you progress.

Grant: I think in practice the pack feels as heavy at the start as it does at the end because you’re so worked that you’re like, Well, I’m still carrying the thing. You take it off at the end and it’s so nice.

I made a lot of navigational mistakes, not big, critical mistakes like repeating [Mount] Shavano at the end, but more dumb things where I wasted a lot of time. I knew I wasn’t taking the optimal route and I did it anyway. A perfect example is where I summited [Mount] Princeton, and I’m coming off of Princeton and there’s a decent descent down into Grouse [Gulch], and instead I went straight down this super-gnarly, super-steep scree gully. I look at it, and I’m like, Eh, this is fine and it’s the right direction. I get halfway down it and I’m like, Man, what am I doing? It’s so much effort. I’m just skidding down this thing. Rocks are going everywhere. I’m getting all caught up. Then I get to the bottom and I have to cross this talus field that is tedious and long.

I made a number of those kinds of mistakes. Coming off of Huron [Peak], I know to stay closer right to pick up the elk trail, and then I went a little bit more direct to the left for no good reason. Eh, I’m going to go straight, and it will be fine. As you know, a 100-foot difference on the route can mean all of a sudden you’re chest deep bushwhacking on a super-steep slope. That was happening, and I was like, Man, it’s so dumb. I had this thing burned in my head, which way to go.

That’s also when you start to be a little more relative about time. Let’s just be honest in what you’re looking for in the experience. Don’t get frustrated with the mistake. You’re going in the right direction. You’re still going to make your objective. You’re making it harder for yourself, but you’re still having the experience you’re looking for even if you’re not maximizing it completely. It’s a weird back and forth that I’d have in my head. Oh, I could be doing this so much more efficiently. I would have finished an hour before if I’d not done Shavano twice. That’s also part of the game.

iRunFar: Ten minutes adds up here, 15 minutes there.

Grant: Totally.

iRunFar: When you start one of these things, there’s this period of time where it’s very blissful and idyllic. Then it changes. Where on the route did it become more serious and hard?

Grant: I was in an extremely positive headspace the whole time. I’d had some really intense lows, but I never got into this, Oh, I’m going to drop. Oh, this is too hard. It was always very much what I expected. You’re 20 hours in, talus is talus, it’s hard. I wasn’t naive about what I was going to encounter. I knew it was going to get pretty real pretty quick. That kind of softens the blow transitioning from the, Whooo, I’m going to nail this, to, Oh, no, it’s all falling apart.

That said, as early as coming off Elbert, it got crazy hot. I top out on Elbert and I’m coming down Bull Hill—I actually saw Hannah Green there [who was also attempting Nolan’s 14]…

iRunFar: I was going to ask you if you saw each other.

Grant: Yeah, I was like, Who’s this person hiking up this obscure area? She comes up and I’m like, “You’re doing Nolan’s, right?” I knew she was, but she looked great and was marching really steady. She’s like, “I’ve got seven hours to finish.” I’m like, “Oh, darn, you’re 53 hours in right now?! You look great…”

That little section coming down to where you run the road over to La Plata, it was very hot there. I don’t particularly like the heat. I actually stopped at the creek below La Plata there and cooled off and drank a bunch of water. You’re in no rush. Take care of yourself and don’t get overheated right now. That was my first little alert to be aware and take care of myself.

Then I came into Winfield right at 10 hours and felt comfortable and good. I also know that that is a third of the way sort of. It’s a good gauge. You’ve only done three peaks, but you have done the three big peaks. You’ve run 30 miles or something at that point, and you’ve done 14k of vert.

Then Huron was okay. Missouri [Mountain] was okay. I was starting to feel a bit run down. Then going up [Mount] Belford, it’s only a short bop over from Missouri, but I just started to feel really tired, so from Belford over to [Mount] Oxford, I was getting really loopy and not feeling good at all. I wasn’t sure what my body needed. I feel like I need sleep, but I’m at 14k right now, and I shouldn’t sleep up here. I’m kind of cold, but also kind of hungry, but also kind of nauseous.

Then a really weird thing happened. I started descending off of Oxford, and I got to 13k, and I can’t really remember what happened for a couple hours. I woke up, and I’m sleeping in a ball on the really steep slope there, steep tundra, gradually inching my way down the hill. You know, it’s these lumps of grass. I’m wedged on the lumps. I’m not laying down at all. I’m inching my way down. I’ve got my puff pants on. I have my rain jacket on which I don’t remember putting on. My shoes are 15 feet above me. I look up and I’m in my running socks. This is not great.

iRunFar: This is how far you’ve inched since you’ve been sleeping. Where’s your pack?

Grant: It’s between me and my shoes. I’m just sort of spread out on the lawn. I retrieved my stuff, and then I went a little lower to those willows where you pick up that little elk path through the willows. I got really confused in there. Wait, what am I doing? Where am I going? I wandered around generally in the right direction. I just had a very odd couple hours there. When I came back to, which was at the creek at the [Mount] Harvard area there, I was like, Alright, that’s exactly what you don’t want to replicate again.

It’s a good exercise because you have to work through it. You have to process it yourself and be like, Okay, you’re just really tired. You’re depleted. Focus on what you can do and what you know how to do. Then you get a bit of a grasp on things again and the sun comes up and you’re back on it. That was probably my lowest point even though I don’t really remember it.

iRunFar: Fast forwarding a bit further along the line, I checked your tracker when you were climbing up Princeton and was like, Oh, he’s really solid. I think he’s going to get the record. Were you also aware of how well you were moving late in your effort?

Grant: You know how it goes when it’s actually happening, it’s pretty freaking slow. You’re just crawling up the hill literally. Your perception of speed is pretty warped. That being said, I maintained this focus all the time, just trying to do every bit as best as I can. If I could move quicker up the hill, go quicker up the hill. I just wanted to keep executing and trying to do it well. I did okay at that.

Like I said, coming off of Princeton and taking the wrong descent… I didn’t feel like I did a great ascent of Tabeguache [Peak] either. I was stuck in the freaking waterfall creek thing when I was like, I know I should be further right. Why am I scrambling up some really sketchy, loose rock with water falling on me? There’s little moments like that where you’re like, I’m not doing as well as I could be, but I was still trying. The intent was there.

iRunFar: Let’s talk about the great Shavano incident of 2018. You tagged the 14th and final summit twice.

Grant: I got super disoriented. I got to the end there and sat on the summit for a second and head in my lap. Okay, if I can just do one last downhill. I’ve got this. I stood up and ran the other way and literally ran because I was feeling, You’re done! You’ve just got a descent to do! I’m bopping along the ridge, and I didn’t snap out of that until I got to the saddle between Tabeguache and Shavano. When I got there, I’m like, Oh, there’s no trail here. Oh, but wait. No, the trail is on the other side of Shavano. I have to redo the ridge.

It’s funny because I think if I hadn’t messed up there, I would have really ran that descent feeling super elated and good. Instead, I was frustrated for a good chunk of that descent. It was getting hot. At that point I was kind of like, Ah, I could have finished in 48 hours, and it would have been kind of sweet to have that. Then you get done and it doesn’t matter. It’s done.

iRunFar: That mentality that you can find yourself in in those moments is so funny. You’re already going to have a really good time, but, Ah, it could have been a few minutes better!

Grant: It’s a good reminder, too, me feeling sort of down on that last downhill there. Now in retrospect, if your resolve is strong, you nearly should never have those moments because you’re unaffected by what’s going on.

iRunFar: Back to the mountains themselves, one of the coolest parts of being on high mountains is being able to see where you’ve been and where you’re going. Drawing the imaginary lines. There are some places in the Sawatch Range where you can draw most of the Nolan’s line. There’s a lot of emotion that that invokes in people. Did you feel that big-picture feeling or were you pretty focused on the details of moment to moment?

Grant: That’s a great question. It’s sort of impossible not to look up. I pretty much took it in at every single peak. That is one of the unique aspects of the Sawatch is you get that sense of the immensity nearly on every summit whether you look north or south. Whoa, I came from there, and I’m going there.

There are moments that stand out in that regard where you really feel the scale. I remember being on top of [Mount] Yale. You look over and see Princeton which is such a monolith from that perspective. You’re just like, Whoa, it looks intimidating and far. Of course, peeking in the background from Princeton is Antero, which is even farther and a big mountain also.

You go back and forth between this intimidation of the scale of the whole thing but also this awe. It’s kind of rad to think of it conceptually but also be in it and doing it. Wow, my little body was here and then it was over there, and now it’s over here.

It goes along with the unsupported aesthetic. There’s a sense of freedom that you just shoulder your little pack and away you go into the mountains. It’s a powerful image for me. When you’re doing it, you can’t be constantly thinking of the aspirational aspect because it’s hard. It’s not quite as dreamy as I’d like to think it was. But you do have moments that you can click back into it. There’s a reason you’re doing it the way you’re doing it, and there’s a reason you’re doing it in those mountains.

iRunFar: Congrats, Joe. Thank you for sharing your experience.

Grant: Thanks so much for taking the time.