[Editor’s Note: Earlier this month, iRunFar Managing Editor Meghan Hicks traveled to Bekoji, Ethiopia, a hub of Ethiopian elite running, to observe and participate in the Girls Gotta Run Foundation program there. Girls Gotta Run is a U.S. nonprofit that awards scholarships to girls and young women in Bekoji to give them elevated access to education, health care, organized run coaching, life-skills development, and more. This week, we’re bringing you daily dispatches from Bekoji. Thanks to Jaybird for sponsoring these dispatches.]

Tuesday

January 8

7:30 a.m.

I step up onto the tarmac, roll right, and head out for a six-mile run through Bekoji, Ethiopia. Bekoji has been called the ‘town of runners’ as it’s a well-known hometown and training ground for elite Ethiopians. Seven Olympic-medal winners have gotten their start in Bekoji so far, including Kenenisa Bekele, Derartu Tulu, and Tirunesh Dibaba–yeah that’s a lot of gold just right there.

In the mornings, dozens of runners take to the streets, hills, fields, track, and forests to train. While a runner is an expected sight, a ‘faranji,’ foreigner in Ethiopia’s official language of Amharic, out running captures everyone’s attention. As much as they look at me, I am also observing them and their home.

In the mornings, dozens of runners train around Bekoji. Here, a group of young men and women warm up before a speed workout. All photos: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Bekoji is also an agriculture and pastoralism hub, with grain fields stretching as far as the eye can see into the rolling highlands. In these fields grows wheat, barley, teff, and other grains. The highest part of Bekoji is located at about 9,200 feet altitude, and the climate is split into a long dry season and a raging wet season, as I am told, the latter of which allows farming to proliferate. Now, in the middle of the dry season, the fields are golden and dormant and I see only a few clouds during my 10-day stay.

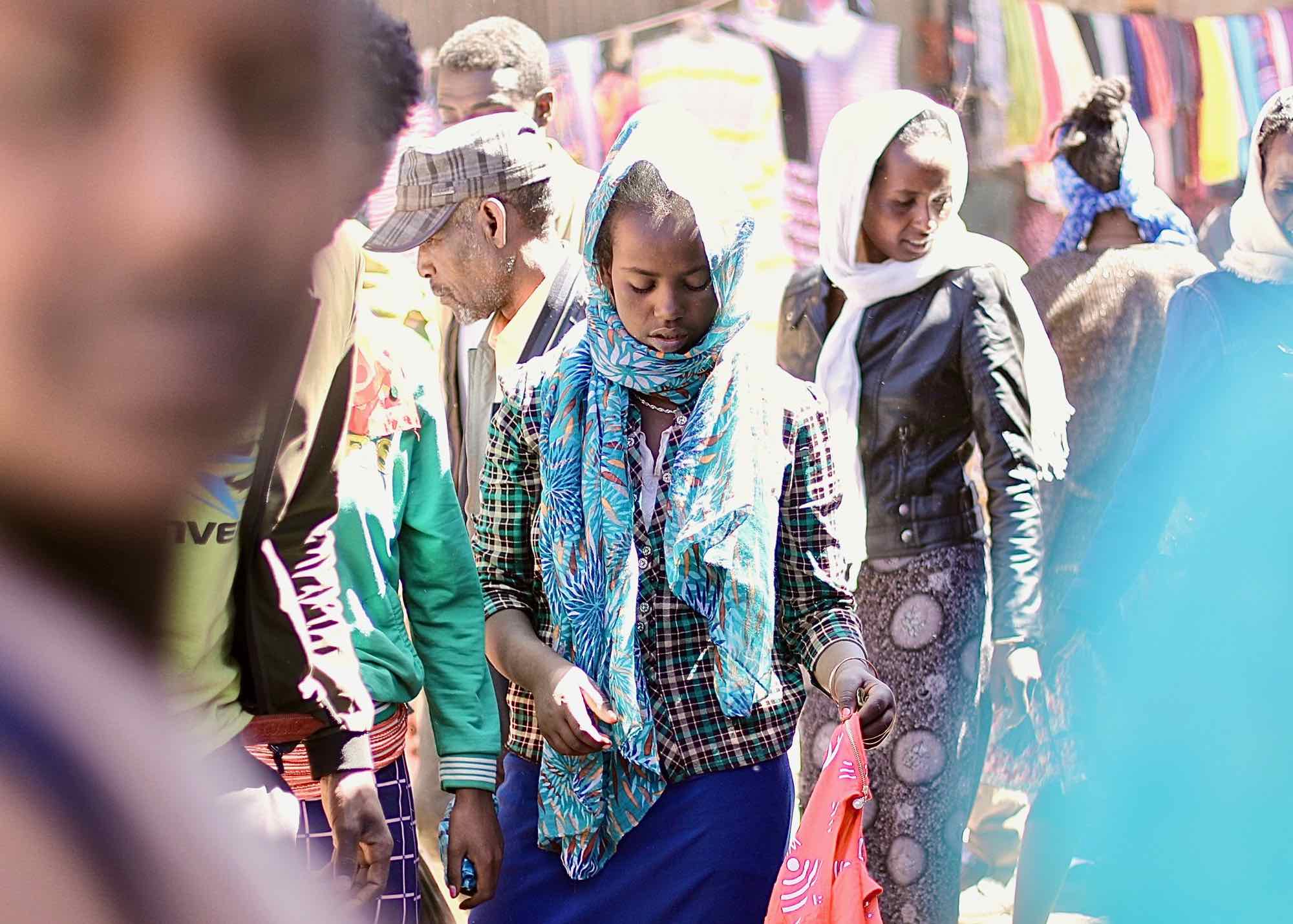

Tuesdays and Saturdays are market days, and since today’s Tuesday, a forever line of people travels this road into town. You name it, and people buy and sell it at the market: plastic shoes, dresses in every color of the rainbow, avocados, papayas, barley, coffee beans, spices, various home-brewed alcohols–watch out for this stuff, it’s strong–sugar cane, baskets, ‘jebenas’ or the clay vessels in which Ethiopians brew their delicious coffee, and so much more. As such, town fills up as the sun rises on market day, pulses hard for hours, and empties out when the shadows grow long. But Bekoji doesn’t go quiet into the night, as a night culture of coffee drinkers, those who seemingly walk the roads in groups for the purpose of socializing, and bar goers come out when the skies darken. A couple club-like spaces even pump music into the night, but these are buttoned up tight right now.

Animals wander everywhere, some leading or being led by people, others just meandering. Horses, oxen, cows, donkeys, goats, and sheep share life with humans here, as beasts of burden or being raised to be or produce food. Oxen are used to work the fields, horses and donkeys pull the ‘garis’ or homemade wooden carts that carry people and supplies, cows make milk, goats and sheep make milk too and are eventually eaten, but generally on the special-est of occasions. Dogs wander, though a surprising number of them wear rope collars or are tethered to the fences cordoning off living compounds and look full bellied and relatively healthy. They are kindly and gentle and clearly pets to someone.

The tarmac on which I run is Bekoji’s main street, and its only paved road. Dirt roads grid out in fairly organized–though bumpy, rocky, and at this time of year, dusty–fashion from the blacktop. The last time a census was made in Bekoji was 2005, but there were just shy of 17,000 people living around here then. Several locals say that they think upward of 30,000 people might live in and around Bekoji now. I can believe that, as the sun has only been up for 45 minutes and there are people everywhere.

In Ethiopia, about two thirds of the population is Christian and one third is Muslim. Traditional religions make up a small percent of the population. In Oromia, the sprawling region containing Bekoji, almost half of people are Muslim and the other half Christian. This difference points to the Ethiopian highlands’ history as a place of Muslim influx. While religion has, at times, been an origin point for historical conflict, Ethiopia is now largely known for its religious tolerance. In Bekoji, I’d even call it coexistence. A church and mosque are both located on the hill above the center of town, a couple hundred yards from each other. Muslims and Christians work together, share friendships, and intermarry.

Most Bekoji-ites live in poverty, when measured on a world standard. In Ethiopia, the gross national income per person is $410 U.S. Only 40% of Ethiopia’s population has access to safe or improved drinking water. Here in Bekoji, drinking water comes from a combination of small drainages–which are quiet creeks now but probably run like little rivers in the wet season–and shared wells. Water appears plentiful enough even in the dry season, but the water coming out of drainages must have contamination issues at times as it’s also used to water livestock and wash clothing.

While 87% of children in Ethiopia start primary school, only about 35% begin secondary school. Child marriage remains a real thing despite a legal marrying age of 18, with 16% of girls being married by age 15 and 41% by age 18. Often young girls are married to men much older than them.

The math shakes out as a pretty tough life for the vast majority of Ethiopians. Despite this, people seem generally happy and psychologically unburdened. If I had to summarize Bekoji in just one word, I’d call it a place of ‘chaos’–a lot of people doing all the things at all hours of day and night. But if you gave me a second word, I’d add ‘levity.’ Even though I’m running at 9,000 feet altitude and my GPS running watch tells me I’m barely breaking the 10-minutes-per-mile barrier, I can feel a certain lightness in the air here. And, as the days go on in my Bekoji stay, I will only become more aware of and possessed by its jollity. There has to be much more to it than just Bekoji’s ‘thin’ air.

References:

- Multiple interviews with Kayla Nolan, December 2018 and January 2019

- Multiple interviews with Sukare Nure, January 2019

- Multiple interviews with Fatia Abdi, January 2019

- Uis.unesco.org/country/ET

- Unicef.org/infobycountry/ethiopia_statistics.html#121

- En.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Ethiopia