Is your overtraining syndrome really relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S)?

Almost a year ago, I received an email with a subject line asking almost this same question. The message was about a paper co-authored by two of my favorite exercise physiology researchers, Trent Stellingwerff and Ida A. Heikura. My interest was piqued.

I’ve shared my personal struggles with overtraining syndrome on iRunFar, and it’s still the article I get the most emails about. Most often I hear from athletes looking for advice as they struggle with chronic fatigue.

It’s hard to help because there are not a lot of satisfying answers yet. So, when another possible mechanism for why you and your running performance might be out of sorts comes along, it’s a good thing for us to explore.

In this article, we’ll do just that. We’ll evaluate the similarities between overtraining syndrome and relative energy deficiency in sport, discuss why the similarities might lead to a misdiagnosis of overtraining syndrome, why getting a correct diagnosis is important, and what athletes and their support systems should watch for based on this new information.

Keely Henninger on her way to winning the 2022 Gorge Waterfalls 50k a few years after recovering from low energy availability and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Photo: Steven Mortinson

What Is Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)?

Overtraining syndrome (OTS) is not a verb; you cannot actively do it. It’s a noun, the destination on a continuum of training stress. We need some training stress to make physiological adaptations and improve our fitness, but we get into trouble when we pair these stresses with inadequate rest.

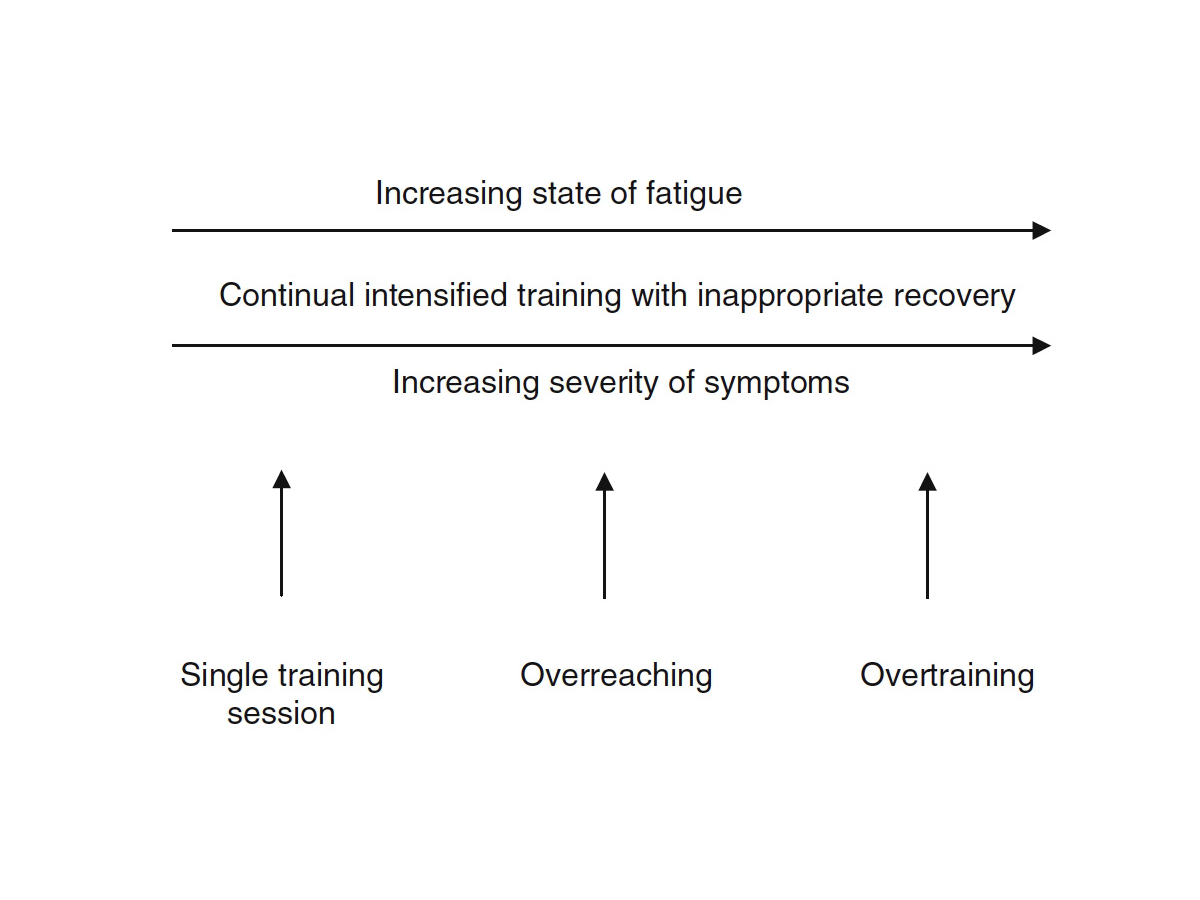

The definitions set forth over the past decade have helped to elucidate the different stops along the overtraining continuum (2).

Overreaching is akin to positive training stress, but a little bigger. Periodically, you can utilize overreaching in a training camp or on a long weekend that, when backed up with adequate rest, can have large positive impacts on performance.

However, if you continue to overreach, without stepping off the gas, you can end up in a place of non-functional overreaching. This is where you are no longer positively adapting to the stress. If you continue to press the gas pedal, you are headed toward the destination of OTS. The difference between non-functional overreaching and OTS is the timeframe of impaired performance, with the former lasting weeks and the latter months.

The outcome of OTS is a combination of factors that decrease performance and impact overall health, including (1):

- Decreased endurance;

- Impaired strength, speed, and power;

- Increased risk for injury;

- Impaired glycogen and protein synthesis (which impairs tissue repair and recovery);

- Impaired coordination and reaction time;

- Impaired sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone);

- Impaired other hormones (luteinizing hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone, prolactin, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, cortisol, leptin, triiodothyronine, and insulin-like growth factor – 1);

- Negative hematological changes (anemia and more);

- Lowered lactate threshold;

- Impaired immune system;

- Negative changes in resting heart rate and heart rate variability; and

- Negative changes in psycho-social-emotional factors (decreased sleep, increased risk of depression, and more).

The idea of the overtraining continuum is that, as overreaching progresses to non-functional overreaching and possibly to overtraining syndrome (OTS), you have an increase in fatigue and severity of symptoms. Image: Halson, S. L., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2004). Does Overtraining Exist? Sports Medicine,34(14), 967-981. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434140-00003 (6)

What Is Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)?

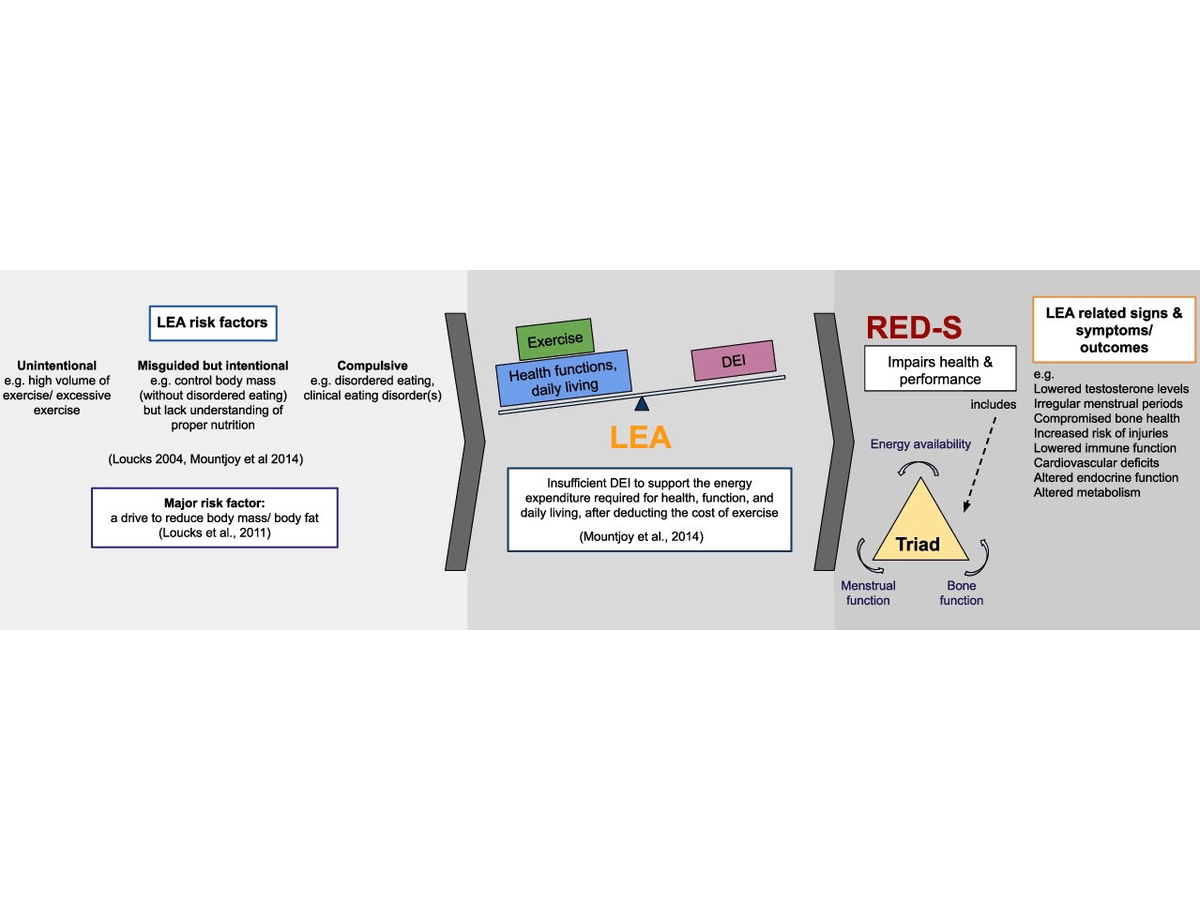

First introduced by the International Olympic Committee in 2014 and further updated in 2018, relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) has gotten a lot of attention in the endurance world of late in an effort to educate athletes and their support systems about the risks of intentionally or unintentionally under fueling (3, 4).

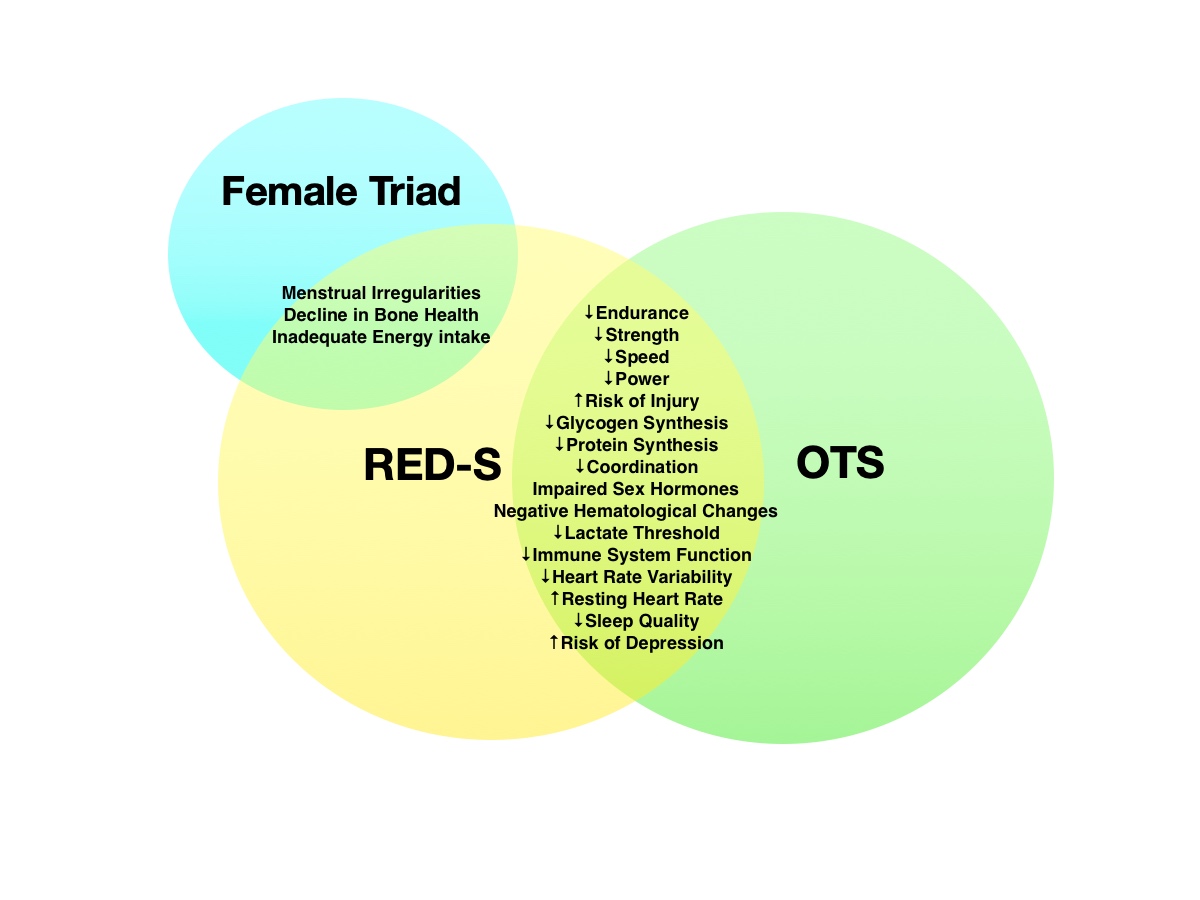

What the introduction of RED-S did was to create a larger umbrella term that took into account the already defined female athlete triad (disordered eating, loss of normal menstruation, and bone-density issues) and added all the other ways low energy availability impacts physiological function, health, and performance, which recognized that all athletes are susceptible to RED-S regardless of gender.

The major underpinning of RED-S is chronically poor energy availability. While this is sometimes intentional (disordered eating), we want to stress that we take part in a sport where it can be hard to meet our high energy demands day after day. If you combine inadequate energy intake with high exercise energy expenditure, you have a recipe for disaster.

I reached out to friend and professional runner Keely Henninger to discuss her experience with low energy availability and RED-S that culminated in a major bone stress injury.

iRunFar: After an incredible 2018 season, in 2019 you sustained a sacral stress fracture. Tell us about that experience.

Keely Henninger: I was ignoring the warning signs my body was putting out for years. My 2018 season looked good on paper, but I was constantly battling highs and lows, overtraining, and under-fueling.

When I started training for 2019, my body was still not cooperating. I’d wake up extremely tired and dreaded going for a run but for a while, I pushed on. When I finally had to stop due to the sacral stress fracture, I felt relieved. I finally had a reason to stop, and my body and mind thanked me.

The injury forced me to take a holistic view of my training, to acknowledge that I had been doing a lot wrong, and reprioritize training and recovery. I wish I could say I nailed the balance as soon as my injury healed, but it took years of slowly adjusting to get to a spot where I have balance, prioritize recovery, and run for the right reasons.

iRunFar: Why do you think it’s hard for athletes to identify low energy availability and/or RED-S when in the throes of it?

Henninger: We are in this sport because we are extremely good at enduring pain and pushing our bodies to their limits. However, there is a level of suffering that is beneficial and a level that is not. We need to be able to recognize [the issues that aren’t beneficial to our health, like] changes in behavior, persistent fatigue, a lack of menstrual cycle (for those who menstruate), a lack of libido (for everyone), and a lack of morning erection (for those who should have one).

For a while losing your period was viewed as normal and a badge of honor in endurance running. We didn’t view this as a warning sign that we were training too hard, but instead that we were training hard enough. As this narrative changes, I hope that more athletes will be able to identify unhealthy patterns and signals before it turns into a big-bone injury and that they will learn to slow down before they are forced to stop.

iRunFar: What do you wish you could tell the Keely of 2018 and 2019?

Henninger: You don’t have to be constantly suffering to be the best runner you can be. We can feel good during workouts, have energy for a life outside of training, and fuel so that we recover and perform to our potential. This doesn’t make us less of an athlete.

We suffer enough during the big races and big days out on the trails, we don’t have to make our lives harder by making all aspects of training a test of attrition. If we treat ourselves with respect, then we will be able to reach our potential. If we constantly beat ourselves down and demand more, then we may break before we ever reach it.

What Keely experienced, and what so many other athletes have experienced, is not dissimilar from OTS in part because this chronic stress — in this case from under-recovery spurred by inadequate energy intake — also creates a disruption in biochemical, endocrine, and sex hormones.

Low energy availability can present from different root causes, including those which are unintentional or intentional (disordered eating). However, it’s an imbalance between dietary energy intake and the amount of energy you need daily to support normal functions and exercise. Being in a chronic state of low energy availability ultimately leads to relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) which encompasses not only the female athlete triad but all other deficits of that state regardless of gender. Image: Sim, A., & Burns, S.F. (2021). Review: questionnaires as measures for low energy availability and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) in athletes. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9. (5)

Is It OTS or Is It RED-S?

So, what are the main differences between OTS and RED-S? Unlike in OTS, RED-S has a sizable negative impact on bone health, including decreased bone mineral density and an increased risk for bone stress injuries like stress fractures and stress reactions (1).

The second difference is that OTS causes central nervous system dysfunction, while RED-S imparts that plus sex hormone dysfunction.

While OTS and RED-S share many commonalities in symptoms — all but bone health — because of under-recovery, they are not the same condition and shouldn’t be treated as such. How do you know which path to go down when looking for answers?

Either path is a little bit of an investigation. This is because both OTS and RED-S are identified by a diagnosis of exclusion. Despite years of trying, both lack a validated universal identifier, something that says, “Yes, you have OTS,” or, “Yes, you have RED-S.”

Traditionally, for OTS this has meant ruling out any natural diseases (thyroid disease or other autoimmune conditions, celiac disease, and more), infections (Lyme disease, mononucleosis, and more), and deficiencies like anemia, and allergies. This list has now grown to rule out other dietary deficiencies, including dietary caloric restriction, unintended inadequate energy intake, and insufficient carbohydrate and/or protein intake. Essentially, you now must rule out low energy availability and/or RED-S to meet the diagnosis of exclusion for OTS (1).

For me, this was a lightbulb moment and highlights the importance of getting an accurate diagnosis early. Understanding which road to head down for appropriate recommendations and prescriptive behavior changes to heal will vary depending on if you are dealing with OTS versus RED-S, and we’ve been missing low energy availability and/or RED-S in this equation for a long time.

It’s long been speculated that only a very small portion of individuals who have been given an OTS diagnosis actually have it, and the review that Stellingwerff and colleagues put together paints this same picture (1). This is largely because low energy availability and RED-S are newer concepts than non-functional overreaching and OTS.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: it’s really hard to overtrain, but it’s really easy to under-recover. And for many, under-recovery likely begins with inadequate fueling. This is a great example of how new research creates new insight.

It would be easy to say that overtraining syndrome (OTS) and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) are linked by looking at this Venn diagram. However, one major difference is that RED-S is a state of chronic low energy availability due to energy intake not meeting your daily needs. While the female athlete triad overlaps with RED-S due to menstrual irregularities and poor bone health, RED-S can impact athletes regardless of gender. Image: iRunFar/Corrine Malcolm

What Should Endurance Athletes and Their Support Systems Be Aware Of?

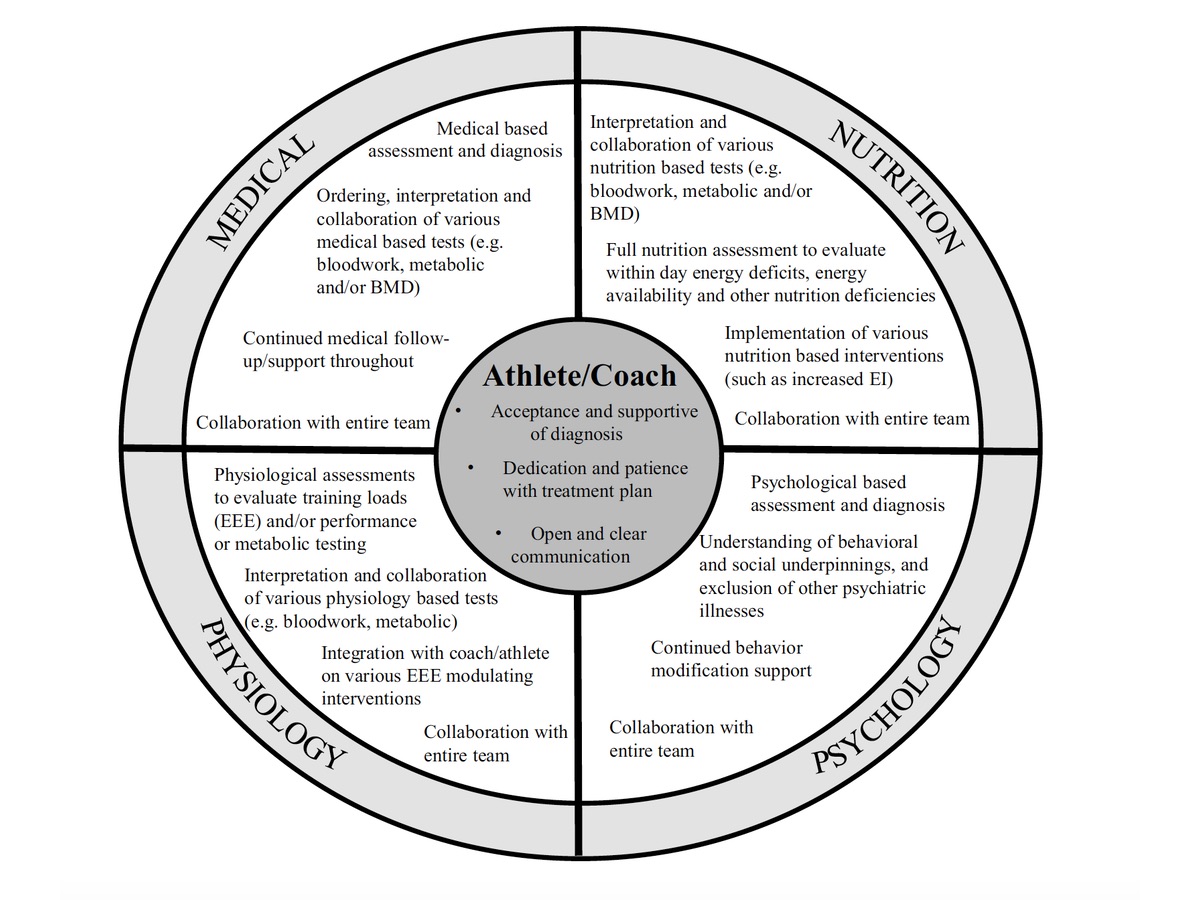

What can you do if you are worried you might fall into one of these two camps? When battling chronic fatigue and a falloff in athletic performance, lean into your support system. Both OTS and RED-S are multifactorial and should be treated with medical, nutritional, psychological, and physiological approaches.

Additionally, one of the most critical findings from the review article was that there was a need for increased awareness among coaches, physicians, physical therapists, and other sports practitioners of the signs and symptoms of OTS and RED-S for early diagnosis and treatment.

Here are the most important points for athletes and their support system to consider:

Be Aware of Menstruation Irregularities

If you are a person who menstruates and are experiencing amenorrhea (absence of your normal cycle) or oligomenorrhea (frequent irregular cycles), there is a good chance your energy intake doesn’t meet your energy expenditure. This is a good time to tag in your primary care provider and registered dietitian to evaluate hormonal disturbances and energy availability. This is most likely a result of low energy availability or RED-S, not OTS.

Watch for Bone Stress Injuries

If you have found yourself with a bone stress injury, particularly a big bone like your femur, pelvis, or sacrum (as these are less prone to straightforward overuse injuries), it’s again time to tag in the professionals. As we mentioned earlier, bone stress injuries are the one symptom that falls squarely in the low energy availability and RED-S camp, as they negatively impact bone mineral density.

Rule Out Natural Diseases

If you are struggling with any of the other symptoms that build off chronic fatigue and impaired performance, tagging in your primary care provider and a registered dietitian is a good first step. They can help rule out any natural diseases or infections and start to evaluate if you are matching your energy intake needs and exercise energy expenditure throughout different phases of your training cycle. This needs to include not only matching your general energy intake needs but also making sure you are taking in adequate carbohydrates and protein.

Discuss Training Levels While Recovering

While training can continue with low energy availability and RED-S, working closely with your coach and medical team to make sure that you are limiting additional stress in order to start to regain balance is important. This likely means a small scaling down of training while increasing daily caloric intake.

For non-functional overreaching or OTS, a period of complete rest is advised. This will vary greatly depending on the individual, but for non-functional overreaching, it could be weeks and for OTS this could be months to years.

This rest should be followed by a gradual rebuild that includes the use of shorter double runs rather than longer single runs to manage stress during the ramp-up to normal volume. This might include steps forward and backward — and that’s why the next piece is so important!

Consider Your Psychological Wellbeing

What about the psychological component? While you may lean heavily into your medical and nutritional support systems, leaning into your therapist and other supports like your coach and family are also critically important during this time.

Being injured — yes, OTS and RED-S are metabolic injuries — is incredibly hard on a psychological level, and having help to lean on and work through this time is critical. Your mental health is as important as your physical health.

This theoretical framework highlights the responsibilities and accountabilities of a multifactorial (medical, nutrition, psychology, and physiology) approach for athletes and their support systems to prevent, diagnose, and treat overtraining syndrome (OTS) and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Image: Stellingwerff, T., Heikura, A. I., Meeusen, R., Bermon, S., Seiler, S., Mountjoy, L. M., Burke, M. L. (2021). Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED‑S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Medicine https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01491-0 (1)

Call for Comments

Please share your experiences with overtraining syndrome or relative energy deficiency in sport. If you feel comfortable, we’d love to hear about your symptoms, diagnosis process, and how you healed from these injuries. Thanks!

References

- Stellingwerff, T., Heikura, A. I., Meeusen, R., Bermon, S., Seiler, S., Mountjoy, L. M., Burke, M. L. (2021). Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED‑S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Medicine https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01491-0

- Meeusen, R., Duclos, M., Foster, C., Fry, A., Gleeson, M., Nieman, D., . . . Urhausen, A. (2013). Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). European Journal of Sport Science,13(1), 1-24. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.730061

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad-Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):491–7.

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(11):687–97.

- Sim, A., & Burns, S.F. (2021). Review: questionnaires as measures for low energy availability (LEA) and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) in athletes. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9.

- Halson, S. L., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2004). Does Overtraining Exist? Sports Medicine, 34(14), 967-981. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434140-00003