Donald Alexander Ritchie, MBE

6 July 1944 to 18 June 2018

One of the greatest ultra-distance runners of all time.

The global ultra-distance community was greatly saddened by the passing of Scotland’s Don Ritchie at the age of 73 back in June. To many current ultrarunners, he is little known except as a name on all-time record lists. It would be impossible to portray Donald in the space of one article, but I hope this gives an insight into a pioneer of modern ultra-distance running who made others, at whatever their level, believe that running ultramarathons was not just possible but also natural.

Donald blazed a trail in the 1970s and 1980s that even now, with ultra distance almost ‘mainstream,’ few have yet matched. Anyone who was privileged to witness Donald running in his prime was usually left dumbfounded by what they saw. For Donald, it wasn’t just that he had the capacity to run all the classic distances up to 24 hours, he could actually ‘race’ them–and race them fast. His pinnacle achievement of running 100 kilometers (62.2 miles), completing 250 laps of London’s Crystal Palace track, in a then-world record of 6 hours, 10 minutes, and 20 seconds in October of 1978, was only recently beaten almost 40 years later, despite valiant attempts from many competent international runners.

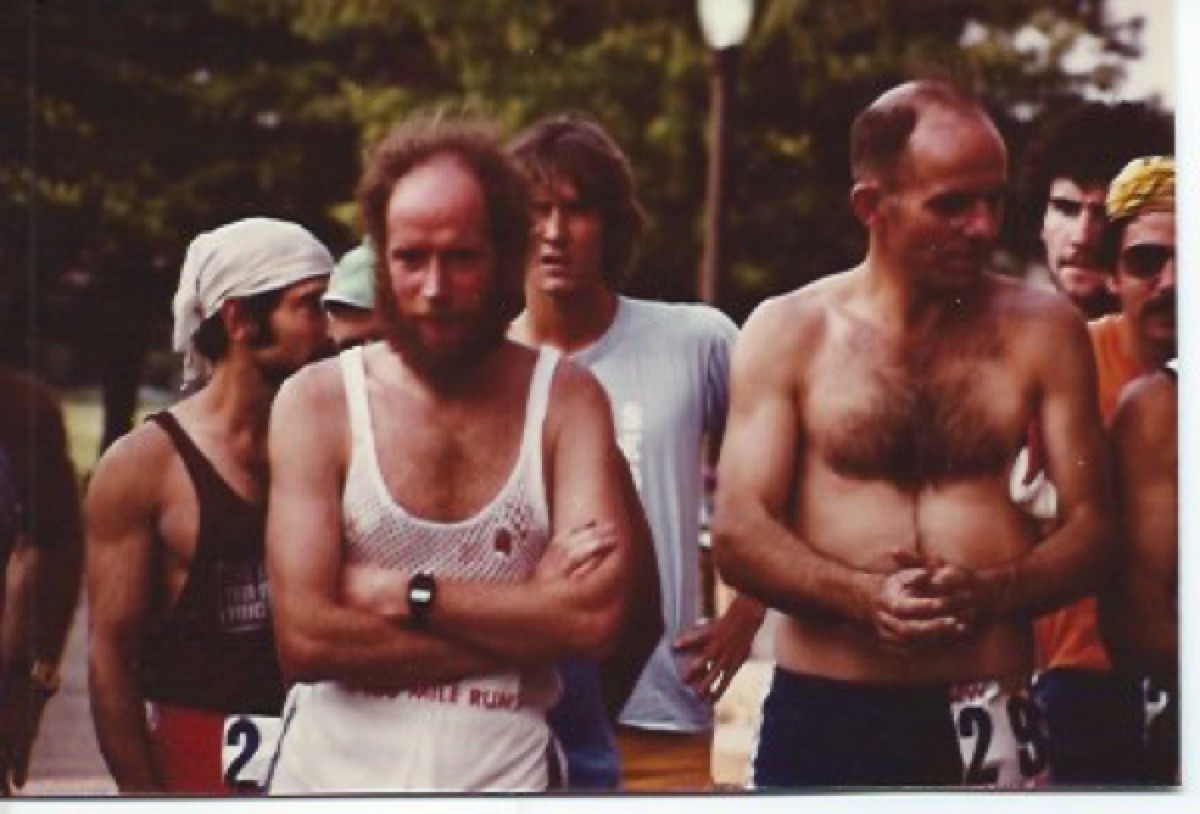

Donald Ritchie on his way to setting a then-world record for 100 kilometers on a track in 1978. Photo: Road Runners Club

I first met him around 1981, shortly after moving to Scotland and discovering that one of his aims was to break a world record in Scotland. Brian Grassom and myself from the fledgling Sri Chinmoy Athletic Club, set up a 24-hour event at the humble surroundings of Coatbridge track, of all places, as it was the cheapest we could find. Donald decided he would like to have a go at the 200k (124.27-mile) record, as he had already broken all the records up to 100 miles in recent years. On a bitterly cold and windy late-October weekend in 1983, with a handful of other runners for company, he completed 500 laps of the track in metronomic style in 16 hours, 32 minutes, and 30 seconds. This comfortably beat the previous mark and along the way he also set a few Scottish all-comers best performances at intermediate distances.

World-renowned ultra-distance statistician Andy Milroy recently summarised Donald’s achievements well in two sentences, “He is justifiably regarded by many as one of the greatest ultrarunners of modern times. With track world-best performances at 50k (twice), 40 miles, 50 miles (twice), 100k, 150k, 100 miles, and 200k (twice), plus world road bests at 100k and 100 miles, he had an unparalleled record in the sub-24-hour events.“

Donald’s ability to run well at such a range of distances is phenomenal. He also had a marathon PB of 2:19:34. Alongside these records go a string of Scottish and Great Britain vests and medals at ultra-distance championships at home and abroad. It is sad to note though, that global ultra championships only really became established toward the end of his running career.

Steeped in the British Harrier tradition of running track in summer and cross country in winter, Donald had track PBs of 14:48 for 5km and 30:56 for 10km while at university. He ran his first marathon at age 22 in 2:43:25 on little serious marathon training. He ran his first ultramarathon, a 36-mile race where he finished seventh, at age 26. Encouraged by this, he gravitated toward ultras and ran what he called his first serious ultra race in 1974, the classic 53-mile London to Brighton Road Race, and finished third.

A spell working offshore on oil rigs led to a life-changing experience. He was knocked off a rig into the freezing North Sea and recalled later that, as he was falling toward the water, he’d always wished he’d learned to swim at school! He was rescued, but on reflection the next day felt he had been given a second chance at life by his “guardian angels.” He moved back to work on dry land as a teacher and his running seemed to have a new sense of focus and rejuvenation. From 1977 and for the next 10 to 15 years, he set a string of records at numerous ultra distances.

The two standout records at the classic 100k and 100-mile distances have totally stood the test of time. Both were set in track events. The 100k time of 6:10:20 set in 1978, still stands as the second-best-ever recorded. If 100k in 6:10:20 sounds like telephone numbers, it breaks down to 5:59 minute/mile pace, or averaging a 2:38 marathon followed by another 2:38 marathon and then another 10 miles at the same average pace. The actuality of the race was a first 50k in 2:59:59 (5:48 pace) with a second half of 3:10:21 (6:07 pace).

It has to be said that even pacing was never really in Donald’s repertoire. I recall a conversation on the topic once. “In any race,” he said, “you go out hard and hang on. If it’s an important race, you just go out harder and have to hang on longer!” It was such a simple-spoken statement, said in a very matter-of-fact tone, and borne out of his quiet determination and deep-seated confidence. It goes without saying that to run the times he did, he always ran nonstop, taking drinks on the run with no faffing around.

His then-world record for 100 miles on the track in 11:30:51 from 1977 is still the third-best-ever recorded. On that occasion, Donald set off as if it was a 100k race too, reaching 50 miles in 5:15:58 (6:18 pace) and 100k in 6:39:59. The last 30 miles obviously became a little interesting, as the second 50 miles took 6:14:53. A considerable slowing over the finally miles, but totally illustrating his innate ability to persevere no matter the obvious discomfort when committed to such an effort.

In July of 1979, he claimed the then-world record for 100 miles on the road in 11:51:11, in an absorbing race around the lake in Flushing Meadows Park in New York. The event was promoted by the New York Road Runners Club. The heat and humidity of a New York summer was an obvious disadvantage for a native Scotsman. Nick Marshall, present at that race, worked out from the lap sheets that Donald’s 25-mile splits for that race were:

- o to 25 miles – 2:32:58 (6:17/mile)

- 25-50 miles– 2:50:45 (6:49/mile)

- 100km split– 6:49:38

- 50-75 miles– 3:07:17 (7:29/mile

- 75-100 miles – 3:20:11 (8:00/mile)

The question often asked is, would a more even pacing have achieved a better time? The answer would remain hypothetical, as it was well-established that Donald only knew one way to race.

Among other achievements he was proud of were setting a then-record in 1989 for the John O’Groats to Lands End run, which is 846.4 miles from one end of the United Kingdom to the other. Don set a then-record of 10 days, 15 hours, and 27 minutes for the distance while raising money for charity. He had also been part of an Aberdeen AC squad that set the relay record for this route in 1982.

He also set up and organised the Speyside Way Ultramarathon for several years. Although on his own admission, his metronomic style was not ideally suited to the rigours of the trails, he was proud to record a victory in Scotland’s longest continuous race, the iconic 95-mile West Highland Way, in 1991.

He was awarded the MBE, the Member of the British Empire, for services to running in 1995.

His success was not just achieved by chance. A sharp brain and willingness to embrace coaching ideas from leading coaches like Arthur Lydiard, together with help from Ronnie Maugham at Aberdeen University’s Sports Science Department, led to a methodical if intense approach to training and racing. The following brief insight to his training appeared in a longer article in the British Road Runners Club magazine in 1996:

“My training ideas have evolved over the years and they are still evolving as I try to integrate my training programme with changing circumstances of work, aging, and family commitments. The keystone of my training for ultras is, of course, consistently high mileage. When I was achieving my best marks for ultra distances I was running an overall average of about 100 miles per week. I like a 10-week build-up to an important race, from about 100 to perhaps 160 miles per week. I usually felt best when I was running about 110. I included fartlek and effort sessions in my training. It is not all steady running.

“The high mileage is important because it trains your body to handle the hardships of a long race and trains your body to metabolise fat into energy. It is important to stress the value of the long weekly run. In my opinion this is the key session and should be of at least two hours duration but should not be too long, otherwise enjoyment is lost and it becomes a drudge. I run a 31-mile course on road and forest tracks two or three times a month. Longer training runs are too time consuming and I do not think they help very much.”

Despite his absolute determination as soon as he pinned on a number, at any distance, in private he was a very quiet, humble man, always willing to offer advice and encouragement to the many people he met in his travels. His good humour and generosity were often in evidence when he would relax post-race, one example being after a victory at the 100k del Passatore in Italy. Donald found at the prize giving that a bonus prize for winning the race was 100 bottles of wine from a local vineyard. Realising there was no way he would be able to transport the 100 bottles back to Scotland, immediately offered to share his winnings with the assembled gathering.

Colin Youngson, a life-long friend and training partner and himself a former Scottish marathon champion, remembers Donald from their university days together:

“He was a promising marathon runner by 1967; at Aberdeen University a close rival who nearly always beat me at cross country; and then a very good friend and clubmate. We climbed Munros (Scottish Mountains over 3,000 feet in height), ran many miles together in training, and enjoyed our races. When he became a world-record-breaking ultramarathon legend it was no great surprise, because this quiet, determined, modest man was utterly dedicated to his running and had an incredible ability to tolerate, without complaint, very hard training and bold, exhausting racing tactics. Donald had immense stamina and a very strong mind. His unbeaten 100k track record, for example, is amazing–consecutive six-minute miles for 62 miles!

“As a personality he never changed: always glad to see his wide circle of friendly admirers; happy to meet occasionally for a few beers (which made him less reticent); never big-headed. When he gave up running seven years ago and health problems worsened, Donald made clear that he had no regrets and was content with his experiences and achievements. For me, it was a pleasure to help by editing some of his detailed and impressive autobiography, which was based on meticulous training diaries and race records. Donald’s wife Isobel and their family were a tremendous comfort. He and Isobel traveled widely and did not waste a minute. Donald Ritchie will be sadly missed by many. He was a superb runner and, more importantly, a great man.”

A great family man, he is survived by his wife Isobel, two daughters, and six grandchildren. Fittingly, Donald was delighted that one of his grandsons, Sunny McGrath of Deveronvale, has inherited the ‘running genes’ and recently competed for Scotland at the WMRA Mountain Running International Youth Cup in Italy.

In conversations with Donald over the years, he was surprised that his 100k world record had stood for so long. He had commented on more than one occasion that when it is broken it will probably be by a Japanese or an African. The Japanese because the 100k, as an event, is rooted in their running culture. He also felt the Japanese mindset was suited to embracing the pain threshold needed to run at sustained pace required. They rarely give up, and have always encouraged marathon runners to embrace 100k when they still have the good, basic speed. The Africans because it is obvious that with their marathon and Comrades Marathon pedigrees, it is just a matter of time before one of them prepares well specifically for 100k and achieves a stellar time.

Ironically, although Donald passed away still holding the absolute 100k best time, set on a track, exactly a week after his passing, Japanese runner Nao Kazami would run 6:09:14 at the Lake Saroma 100k on the road to eclipse the almost-immortal 6:10:20 that had stood for nearly 40 years.

His overall determination to simply bring out the best in himself and encourage others to do the same was best summed up in a meeting with Sri Chinmoy, the respected spiritual teacher and running enthusiast, who in conversation commented, “You are a great champion, who has made the seemingly impossible, not just achievable, but totally inevitable.” His legacy has certainly helped inspire the current successful generation of Scottish and British ultra-distance runners at home and abroad, and will endure for future generations.

[Author’s Note: I would like to acknowledge the assistance of statistician Andy Milroy and Ian Champion of the Road Runners Club for help in compiling this article. Also Colin Youngson who helped Donald in compiling his book, The Stubborn Scotsman. Lion Caldwell too, currently a doctor with the U.S. ultra squad for help with pictures of the 100-mile race in New York, a race he was a participant in! As well as being an experienced ultrarunner and long-time friend of Don Ritchie, I am part of the team support for both the Scottish and Great Britain ultra-distance squads.]