This month, I’m wading into the saturated field of performance hacking to make a case for why you should return to the starting line of the 100-mile ultramarathon you finished at least once before, even if you already have the belt buckle.

After a busy month at my day job when my training goals had to be adjusted, I was looking for reassurance for my upcoming 100 miler. I wondered: How often do runners improve their performance at a given race?

It turns out that if, at first, we don’t succeed, we should run that 100 miler again! When it comes to 100-mile races, and as we’ll discuss in depth throughout this article, the data show that the majority of participants improve their performance when they return for multiple attempts at the same event.

The Dataset and Methods

We began exploring this question by creating a sample dataset based on every edition of six different 100 milers. I favored events for which I already had race results handy — UTMB, Western States 100, the Javelina 100 Mile, and the Superior Fall Trail Race 100 Mile — and then I added the Thames Path 100 Mile and Tarawera by UTMB 100 Mile for improved geographic representation. I counted the runners who started an event multiple times, so runners who did not finish (DNF) were included, but runners who did not start were not. This produced 10,949 data points.

Please note that some individual runners may have multiple data points each because they ran multiple races at least two times each. For example, Fiona Hayvice has run the 100-mile edition of Tarawera — where she podiumed in 2021 — three times and the Western States 100 — where she finished in the top 10 in 2017 — twice.

A joyful Fiona Hayvice upon finishing fifth at the 2017 Western States 100. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

For this article, we define improved performance as finishing a race after DNFing on the first attempt or finishing faster than the first time a runner completed that event. We should note that, under this definition, a runner could do a single event five times and run their personal best on their second attempt, and we consider this an improvement – even if that runner gets a DNF on each of their third, fourth, and fifth attempts at the race.

We have no realistic way of determining which athletes may have trained on a course or how much time they spent on very similar terrain, so the definition of previous course experience in this article is limited to whether the runners have previously attempted the race.

Finally, we note this dataset compares times as they appear in the race results. We did not add handicaps for running in unusually hot or cold conditions or on an adjusted course. We know that, in practice, course conditions impact race performance. However, to keep the methodology clear, we use the imperfect-but-defensible standard of comparing finishing times to each other without subjectively passing judgment on which years were more challenging to complete a given race.

The Likelihood of Improving at a 100 Miler Increases With Repetition

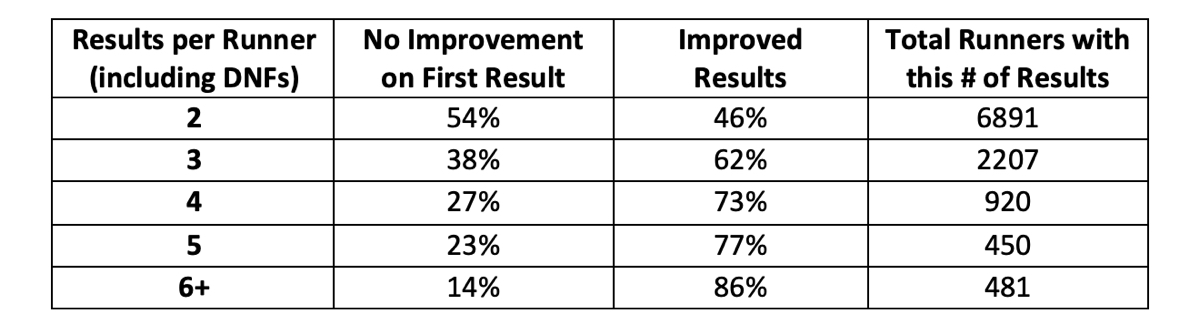

The likelihood you will improve your result at a given 100 miler appears to increase every time you run it. While 46% of runners with two results at the same race improved their result on their second running, that rate climbs steadily for each repetition. Among runners who have done the same event 10 or more times, virtually all improved their performance.

There may be other factors at play, though. For example, it’s possible that a record of improved performance is part of what draws runners back to a particular race or that the runners who love one race enough to do it 10 or more times are also the most motivated to improve their performance at it.

The chart and graph below show that the proportion of runners who improve on their first result at a 100 miler increases with each repetition of the event.

A chart outlining how the proportion of runners who improve on their first result at a 100 miler increases with each repetition of the event. Image: iRunFar/Mallory Richard

A graph showing that the proportion of runners who improve on their first result at a 100 miler increases with each repetition of the event. In other words, runners who have started a 100-mile race five times are more likely than runners who have started it twice to have run faster (or finished) at least once compared to their first result at the event. Image: iRunFar/Mallory Richard

Improvement in Repeated 100 Milers Is Consistent Across Genders

The performance-enhancing benefits of returning to a 100-mile race where you have prior experience on the course are remarkably consistent, regardless of gender.

Among women, 54.47% of runners who returned to one of the 100-mile races in the dataset performed better as veterans than they did as rookies.

The percentage of men who improved was nearly identical, at 54.37%.

The dataset contained one runner who identified as nonbinary, and they ran faster in their second attempt at their chosen 100 miler. (That’s a 100% improvement rate! Nicely done, even if the size of the dataset means it’s not a statistically significant finding.)

Improvements Are Most Common Among the Fastest Runners in Repeated 100 Milers

In the book “The Sports Gene,” David Epstein suggests the “Matthew effect” may apply to the realm of sports. It’s a reference to the Bible passage, stating, “For to every one who has, will more be given …” Epstein was describing how some of the best athletes have genetic predispositions that promote exceptional athletic performance, and their performance increases at prodigious rates with training and experience. These athletes are good to start with and just get better.

This concept seems to have bore true in the dataset. We were surprised by this finding. We expected that since the fastest runners already minimize their time at aid stations and push hard throughout their 100 milers, perhaps they have less room for overall improvement.

In contrast, I once struggled so much in a 100 miler that I took a nap on the side of the trail. I could improve my time at that race just by eliminating the nap on my next attempt.

Instead, the fastest runners were the most likely to improve with course experience.

To explore this concept, we created bins or groupings of athletes based on their fastest finish at a race, calculating their time as a percentage of the total allowable time. For example, Kilian Jornet’s fastest finishes at UTMB were 19:49 in 2022 and 19:16 in 2017. If runners can take up to 46.5 hours to finish UTMB, then Jornet’s fastest finishes fall into the grouping of using between 40% and 49% of the maximum time allotted to runners for an official finish.

The graph below shows that rates of improvement were highest among faster runners.

A graph that groups runners based on their fastest results at a given race. Since the races in this dataset had different time caps, the finishing results were calculated as a percentage of the total time. Note that the fastest runners (those in the first two groupings) represent a small proportion of the total runners. For example, the dataset contained 88 runners whose fastest result placed them in the 40% to 49% category, compared to 2,872 runners who used over 90% of the allotted time to get their fastest finish. Image: iRunFar/Mallory Richard

Avenging the 100-Mile DNF by Returning to the Same Race

If you DNF your first 100 miler, the data suggest you should try again. If you are looking to tackle unfinished business at a race, you can find some encouragement in knowing 62% of runners eventually finished a race where their first result was a DNF. On 2,510 occasions across this dataset, runners returned to a race they previously DNFed and got a belt buckle — or finisher’s medal — for their trouble.

Courtney Dauwalter winning and setting a course record at the 2022 Hardrock 100 after DNFing the previous year’s event due to stomach issues. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

That said, a finish isn’t guaranteed, as 1,507 runners in the dataset DNFed all their attempts at their chosen 100 miler. We’d like to think that, race lotteries and entry processes permitting, those runners will also avenge their DNFs sometime in the future.

If we can stray from data analysis for a moment, we’d like to take a second to acknowledge the guts it takes to tackle any race where a runner has previously DNFed, especially more than once. There are so few aspects of our running where we mortals can claim common ground with the likes of Jim Walmsley, who had a DNF at the Western States 100 before going on to win on three successive occasions and set a course record in the process. Having the courage to tackle a course or event that has already bested a runner at least once is something to be proud of.

Speaking of people who make the rest of us feel like mere mortals, the dataset contained a subset of remarkable folks who had 20 or more results at the same event. Tim Twietmeyer leads the pack with 25 results at the Western States 100, where Scott Mills, Jim Scott, Mike Pelechaty, Gordy Ainsleigh, and Dan Williams also have 20-plus results in the same event. At the Superior Fall Trail Race 100 Mile, Susan Donnelly and Stuart Johnson each boast more than 20 finishes — and counting.

While there are too few people in this club to draw any statistically viable conclusions, Susan Donnelly’s performances at the Superior Fall Trail Race 100 Mile raise the question of whether drawing on course experience is one strategy for maintaining consistent performance over decades. Of Donnelly’s 22 finishes at the event, 19 fell within 10% faster or slower of her average finishing time.

Tim Twietmeyer, who has finished the Western States 100 a record 25 times, at the 2021 American River 50 Mile. Photo: Joey Hollister

Dramatic Time Improvements Are Rare When We Repeat 100 Milers

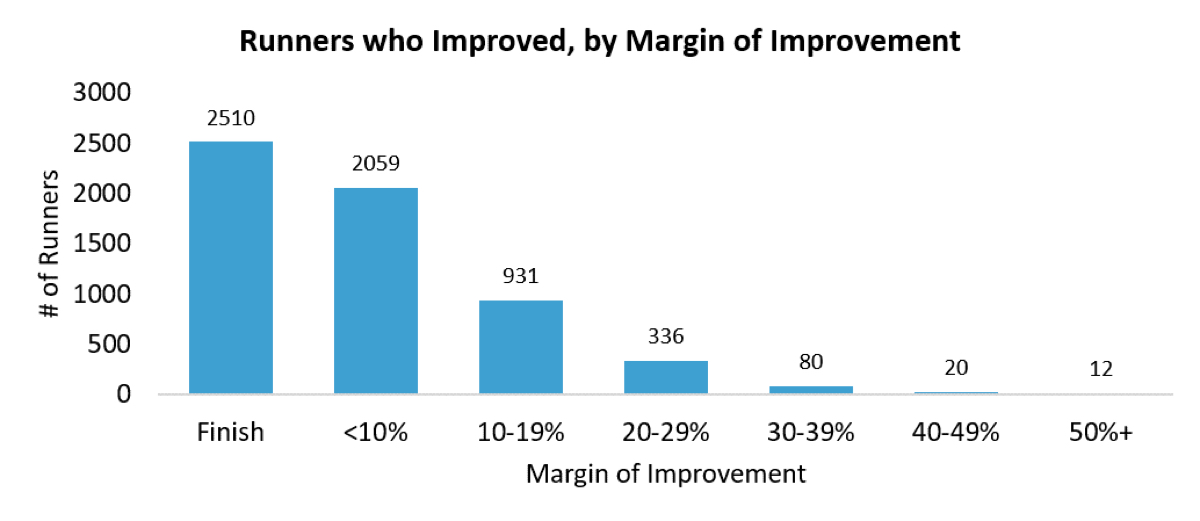

If your first result at a given race was generally reflective of your potential, then subsequent improvements are typically modest. The most frequently observed kind of improvement in the dataset was for a runner to finish after getting a DNF on their first attempt at a race.

After that, as you can see in the graph below, a respectable number of runners improved their performance by up to 19%. The number of runners who have improved their performance by wider margins is much smaller in comparison, though that makes their feats all the more impressive. (A quick shoutout to Nathan Moody for shaving 10 hours off his previous time at the 2022 Javelina 100 Mile to finish seventh — one of the biggest performance improvements we identified in the dataset!)

A graph showing the degree to which all runners from the dataset generally improved their 100-mile races in repeat performances. Image: iRunFar/Mallory Richard

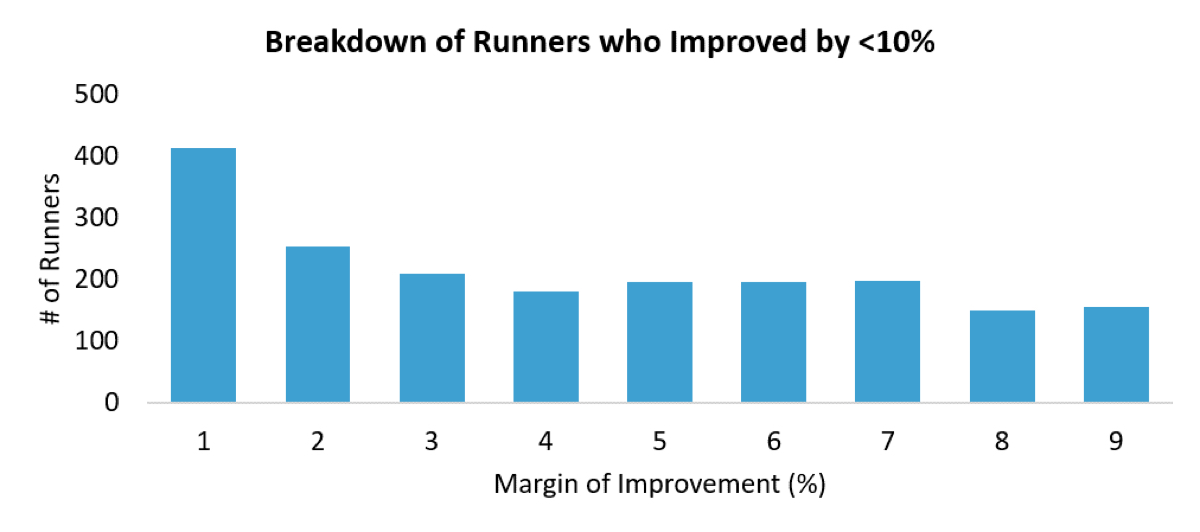

Since there’s a big difference between a 1% improvement and a 9% improvement in terms of the effort — and sometimes luck — required to attain them, I’ve further broken down the runners who improved by under 10% in the chart below. Once again, it shows that marginal gains are the most frequent, with 413 runners improving by up to 1%.

A graph showing the degree to which runners from the dataset who improved by under 10% generally improved their 100-mile races in repeat performances. Image: iRunFar/Mallory Richard

Conclusion

With the challenges we encounter over the 100-mile distance, it’s rare to feel like we’ve run a perfect race. We commonly hobble away from our 100 milers with the sensation that we could improve upon our performance.

The data we share in this article seem to corroborate our feelings that, by repeating the same 100-mile race a couple of times, our chances of improving our performance continue to rise in each attempt.

However, in the end, whether you run the same 100 miler more than once is a personal decision. If seeing new places is what motivates you to race, then the performance benefits of repeating the same race may be diminished for you. And for many of us who return to a particular race again and again, it is often the community built around that race that is a bigger draw than the potential for a new personal best.

But if improving your performance is a draw for you, then the data suggest that, if at first, you don’t feel you did your best, then go ahead and run that 100 miler again.

Call for Comments

- If you’ve run the same 100-mile race more than once, what has your experience been?

- Do you think the benefits of prior course experience apply to shorter distances as well?

- Do you think the benefits of prior course experience vary based on a race’s terrain?