[Editor’s Note: Welcome to a limited-series column by runner and data analyst Mallory Richard where we dive into data from the sports of trail running and ultrarunning to look for trends, see our sport’s progression through time, and have fun playing with numbers.]

Where is UTMB won? Across every last kilometer of the course.

As already covered in iRunFar’s previews of the women’s field and men’s field, respectively, the 2022 edition of UTMB is shaping up to be another exciting one. These elite runners possess a variety of strengths and racing strategies.

I have wondered for a few years about the best strategy for racing UTMB. I haven’t done the race or seen the course myself, so my curiosity is primarily as a fan of the sport.

I remember that Jim Walmsley’s aggressive strategy in 2017, where he eventually finished fifth, fueled discussion about the relative merits of setting the pace early in the race. It likewise stuck with me that Pau Capell’s 2019 win was described by iRunFar as “an outstanding line-to-line performance,” with an emphasis on how remarkable it was that Capell maintained a lead over three-time winner Xavier Thévenard and so many other top runners for the entire race.

I had spent the first half of that same 2019 race compulsively refreshing the live tracking for updates on whether Courtney Dauwalter had caught up to early leader Miao Yao in the women’s race. While I have the highest opinion of Dauwalter’s abilities, I never treated it as inevitable that any runner would catch Yao, though she eventually did and won the race.

China’s Miao Yao running in the lead about 66 kilometers into the 2019 UTMB. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

It left me wondering, is there such thing as a typical UTMB win? Just how rare is a line-to-line win? If it’s more common for UTMB winners to let their fellow competitors set the pace early on, when do they take the lead?

To try to answer these questions, I sifted through past UTMB splits — excluding 2012, when the event was held on a short course, and 2003, for which splits aren’t available on the UTMB website. I looked at how many of the eventual winners were in the lead at a given checkpoint. There is a lot of talk of how runners change position at the Western States 100 starting around Foresthill, which is 62 miles into that 100-mile race, with the eventual winners emerging as the people who managed the miles leading up to that point effectively. Was there a similar point on the UTMB course?

The Men’s UTMB

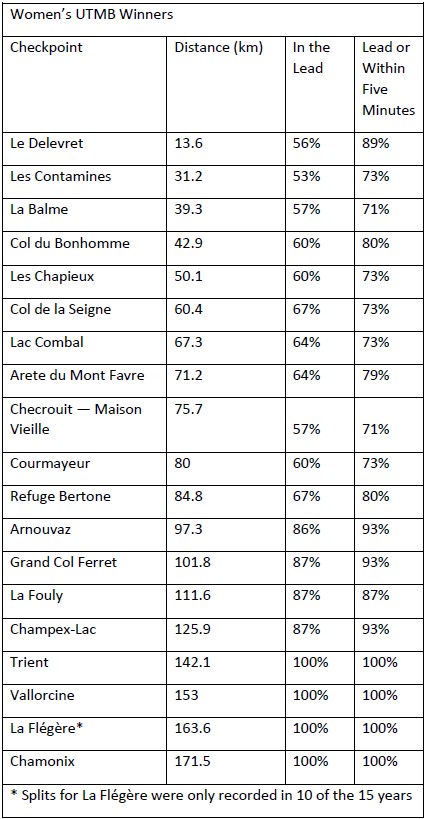

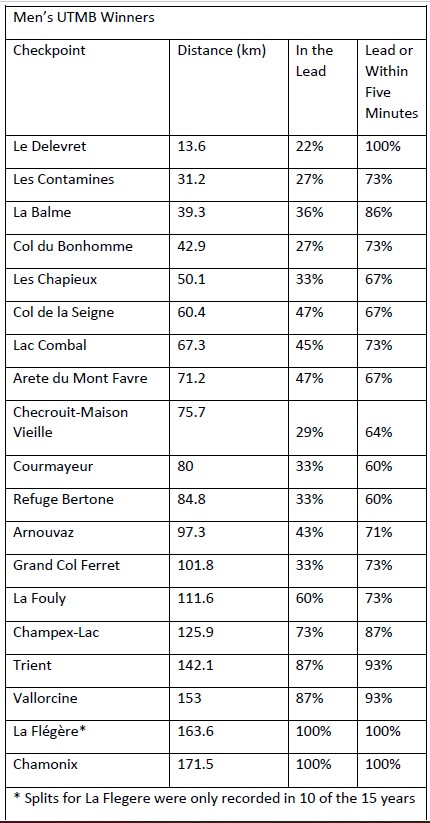

The table below shows the names of checkpoints that have been used consistently at UTMB since 2009, along with the distance in kilometers of those checkpoints. The UTMB has changed many of its checkpoints over the years, so I calculated the percentages based on the total number of splits available. For example, only 20 of the 30 men’s and women’s winners had splits recorded at La Flégère (164k).

Pau Capell at Champex-Lac. He was untouchable by everyone at the 2019 UTMB. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

The third column of the table lists how many race winners were already running in the lead at each of those checkpoints. I only considered a runner to be in the lead if they were the very first runner to pass through the checkpoint. In some cases, the eventual race winner was mere seconds behind another runner, but I classified those runners as being “within contention.”

As you’ll see, it’s true that Capell was relatively unusual for being in the lead by Le Delevret (13.6k). On the other hand, it appears uncommon to lose touch with the lead pack and still win. The right-most column of the table below shows how many eventual winners were either leading or within five minutes of the lead at each aid station. The majority of race winners fit those criteria across every checkpoint in the table below.

What the data seems to indicate, then, is that a men’s runner can win UTMB without being the first through every checkpoint, but they cannot win without being aggressive, and they absolutely cannot fade. When I mentioned this to Meghan Hicks, who has years of on-the-ground experience covering the race for iRunFar, she added, “We’ve anecdotally speculated the descent from Grand Col Ferret (102k) to La Fouly (112k) to be a common turning point for who wins the men’s race, and the data seems to corroborate this.”

For the men’s race, the data arguably provides some validation to runners like Jim Walmsley and Pau Capell, who have taken big risks at UTMB. From where I’m sitting on my couch on the Canadian Prairies, I dare not comment on whether, when, or where runners with podium aspirations should push themselves and their competitors. I will humbly note, though, that the imperative to push is so evident I can read it in the splits from a continent away.

Capell and Walmsley are back at the 2022 UTMB. So is Kilian Jornet, who likewise set the pace for the entirety of his winning UTMB run in 2009. In 2011, the splits suggest Jornet deployed a slightly more conservative strategy, at one point running up to 12 seconds off the lead.

The Women’s UTMB

The women’s race is a little different. Approximately half of the eventual winners were already leading by the first checkpoint. Among runners who took the lead later in the race, they typically made their move earlier than the men’s winners: Two-thirds of the women’s winners were in the lead 60 kilometers into the race. At Grand Col Ferret (102k), 87% of the women’s winners were already in the winning position, compared to just 33% of men.

Krissy Moehl (2009) and Núria Picas (2017) are the only two women to win on the full UTMB course to have taken the lead after Champex-Lac (126k). Late-stage presses are less common in the women’s race partly because the start-to-finish domination that made Capell stand out in 2019 is almost normal among these world-class women. Clearly, the lead women are racing aggressively. They are willing to set the pace themselves and spend significant portions of the race looking over their shoulders for would-be challengers.

No previous women’s UTMB champion is back for the 2022 edition, but we’ll see previous podium and top-10 finishers alike on the start line, to include Mimmi Kotka, Katie Schide, and Fu-Zhao Xiang, so let’s see what strategies they employ.

The UTMB data on runners’ splits through different checkpoints gives us another way of appreciating facets of the women’s and men’s races, respectively.

As race day arrives, it will be fun to follow the frontrunners to see whose aggressive pacing pays off, and who pays for their paces. While the eventual winner is likely to be in the lead pack at all times in both the men’s and women’s races, in truth, there’s only one spot on the course where being first matters.

Call for Comments

- Looking at UTMB’s winning performances is only the tip of the spear. What other questions would you pose when looking at 15 years’ worth of UTMB splits?

- Data is fun, but running UTMB is probably more fun. Do you have any personal insights on optimal pacing and racing strategies for UTMB?