The first article last month on the hip-hinge running posture generated a lot of great discussion, as well as good insights and questions. Because this is such a crucial characteristic of efficient running–especially over trail running and ultrarunning distances–I return to the hip-hinge concept to answer questions and add clarification in this second article. Specifically, we cover:

The first article last month on the hip-hinge running posture generated a lot of great discussion, as well as good insights and questions. Because this is such a crucial characteristic of efficient running–especially over trail running and ultrarunning distances–I return to the hip-hinge concept to answer questions and add clarification in this second article. Specifically, we cover:

- The difference between being hip-hinged and ‘running tall;’

- Hip hinge versus pelvic tilt or back arch;

- The relationship between hip hinge and the knee and ankle; and

- Strengthening strategies for the hip hinge.

In addition to the written explanation in the balance of this article, this video addresses each bullet point:

Hip Hinge Versus ‘Running Tall’

Many runners (as well as coaches and healthcare professionals–including me, at times) have emphasized the importance of ‘running tall.’ But with many run-stride cues, what does that mean? I believe what most coaches are looking for is a general neutral posture, which includes a relatively straight spine and specifically avoiding a slumped-forward trunk position. Others, including some leading biomechanics researchers, advocate for a more extreme position through a fully upright (vertical) trunk with lumbar extension.

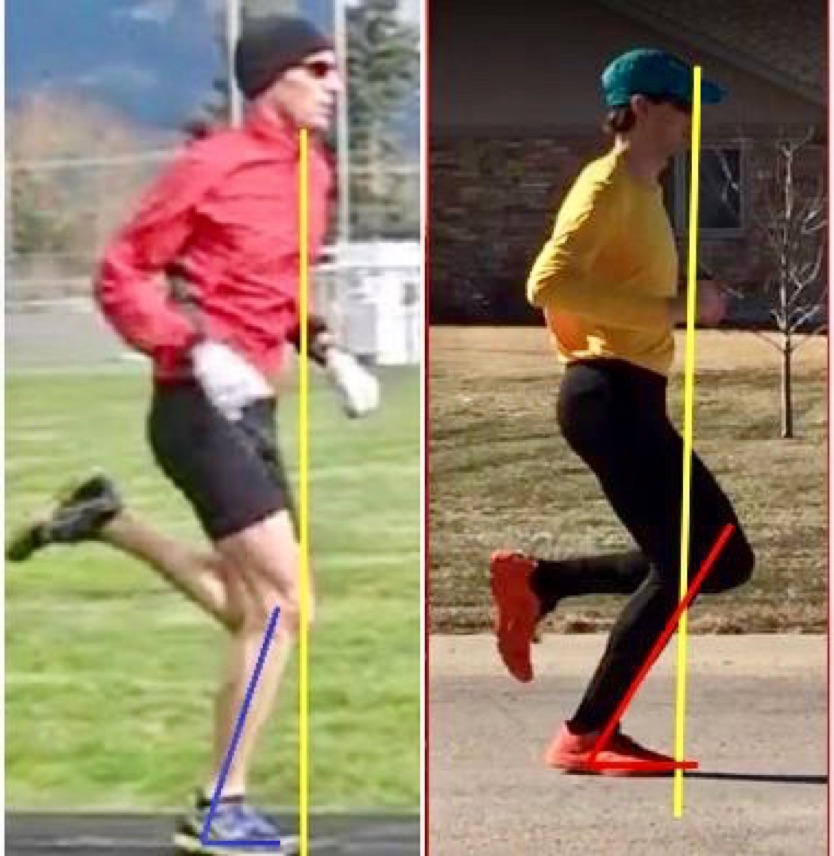

As discussed in the first article of this two-part series, this ’too tall’ posture, typified by excessive lumbar extension and a vertical trunk, is detrimental because it causes a trunk-muscle imbalance. This means hyperactivity of the extensors and decreased anterior core (abdominal) activation, which often results in a loss of hip hinge, an over-stride landing, and increased landing forces.

However, I believe it is quite possible to still be tall–to be neutrally straight through the spine (a straight line from ear to hip)–but to still adopt and maintain a hip-hinged, trunk-forward orientation.

Hip Hinge Versus Pelvic Tilt

In the same vein, I also think it is possible and necessary that a hip hinge occurs without any extreme tilt of the pelvis. Going back to the first running-posture article, neutral posture is a balance in angling, of both the spine and pelvis. Adopting a hip hinge means an isolated motion at the hip, with no motion at the pelvis. The pelvis should remain perpendicular to the line of the spine.

Hips, Knees, and Ankles: ‘Staying Tall’ in the Leg

Balanced motion and position of each motion segment in the leg is crucial for efficient running. From the feet to the pelvis, each joint slightly flexes (bends) to a different degree, and that recipe is key to our best movement. Not enough or too much flexion can be both inefficient and painful.

At one extreme is the ‘too tall’ running posture we talked about a few moments ago and outlined in the last article, too. This is where there is nearly no flexion in the foot, ankle, knee, or hip. This leaves few options for how to propel, so many ‘too tall’ runners either bounce up and down at the knee and ankle, and/or they hyperextend at the low back. This type of stride is a rather dangerous possible side effect from trying to adopt a ‘run tall’ strategy.

On the other extreme is to be too flexed. In a hip-hinge position, excessive knee and ankle flexion ironically weakens the leg by decreasing the power of the hip to push off behind. Part of this weakness can be attributed to a shortened lever at the hip. The rest of the weakness originates in the knees and ankles taking too much of the work. But even worse than a weakened push-off is hyper-flexion at the knee and ankle which tend to cause overloading in both of those joints. In this deflated position, the tissues around the knee and ankle get overstretched. This is a prime cause of chronic knee, calf, plantar, and ankle pain.

The sweet spot is only a slight amount of hip flexion to create the hinge, with an even slighter amount of knee and ankle flexion. In essence, the hip has the most flexion, while we run pretty tall at the trunk and in the rest of the leg.

Hip Hinge + Pawback = Running Power

In a comment to the previous article, a reader asked how to best propel in this position. My best answer to this question is the precise strategy that helps to reinforce that tall leg position: pawback.

Pawback may be the most potent propulsive running cue that exists. One single motion not only improves landing efficiency (by decreasing over-stride landing) and improves hip-extension power, but it also helps to reinforce the tall leg position. A forceful hip-plus-hamstring pull helps to maintain the tall leg by pulling it straight beneath the body. Meanwhile, the rotary action prevents excessive landing force that might otherwise force both the ankle and knee to flex. Indeed, it is an anti-bounce mechanism!

Reinforcing the Hip Hinge

Here are some strategies for how to best reinforce the hip-hinge position:

The ice-skater exercise. One of my favorite whole-body running strength exercises, this exercise allows a runner to practice all elements of the run posture–hip hinge, neutral trunk, and a pretty tall leg–in one exercise.

The deadlift. This exercise, by definition, is a resisted, full-motion hip hinge. It strengthens the hamstrings and glutes to the max, and it also helps reinforce the neutral trunk position.

Upper-body strength work. You can do any upper-body exercise in a hip-hinged position (either symmetrical- or staggered-feet positions). Bicep curls, bent rows, and bent flies are my favorites. The key is to push the feet into the ground to maximize the leg utilization (which includes stability at the knee with the quadriceps muscles), and to go slow and steady to prevent any trunk flexion or extension.

Hopping. Single-leg plyometrics are a great place to practice hip-hinged posture, and such position is crucial to strengthening the hips (and not overusing the quads and calves) when hopping.

Uphill hiking. Hiking represents a slower (and very trail- and ultramarathon-specific) way to practice the hip-hinge position. (This article and video are a refresher on uphill hiking). A treadmill is a great place to work on prolonged hip hinging while going uphill. I recommend at least 10% grade (about the average steep hill one might encounter in American trail races).

Final Thoughts

Finding and maintaining a balanced head-to-toe running posture can be a huge challenge. But doing so is your chance to relieve pain, improve your top-end speed and endurance, maximize performance, and, above all, enhance your enjoyment.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- What questions do you still have about the hip-hinge posture and how to practice and use it?

- Do you think there are certain kinds of running and other exercises where you use better hip-hinge posture than others, such as in the gym or when powerhiking uphill? Where could your running practice use a little more, ahem, practice in hinging at the hip?