The Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run.

The Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run.

The very name has sent shudders of fear and reverence through the spines of trail runners for approaching two-and-a-half decades. Thought up in 1991 by Gordon Hardman; developed over the 1991 to 1992 fall, winter, and spring by Gordon Hardman, John Cappis, and Charlie Thorn; and enacted for the first time in the summer of 1992, the Hardrock 100 self-identifies as a post-graduate-level ultramarathon because it takes place on remote, high-altitude terrain with limited support. Its saying is ‘Wild & Tough.’

[Special thanks to Smartwool. It’s their generous support that made this long-form article possible!]

‘Wild & Tough’ at Island Lake on the Hardrock 100 course, during the 2015 race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

However difficult Hardrock feels when one is in the deepest throes of the race, co-founder and Course Director Charlie Thorn insists that those to whom this event is annually dedicated are the toughest ones. Explains the event’s official dedication, decreed annually in the detailed course description written by John Cappis and Charlie Thorn:

“In the 1860s, hardy prospectors began to come into the San Juan Mountains to search initially for gold but soon including silver. The initial focus was in the vicinity of Baker’s Park (current location of Silverton) but soon spread to the surrounding area. The establishment of permanent settlements in the San Juan Mountains was well underway in 1870s when Silverton was incorporated. By the end of the nineteenth century there was a veritable army of prospectors climbing among the lofty crags in hopes of making a fortune mining the minerals hidden between the peaks and in the valleys. Most of the towns, cabins, stamp mills, aerial tramways, tipples, smelters, and adits the miners built or dug have succumbed to the ravages of the elements. Large piles of unproductive rock (tailings) mined from the steep hillsides are often the only remaining visible evidence that once here labored men with dreams of finding buried wealth. Foot trails, burro trails, wagon roads, and railroads were constructed for transporting working materials to the mining sites and hauling ore from the mines to the markets. This run follows routes laid out by the miners and is dedicated to their memory.”

In this video, Charlie Thorn explains exactly why he thinks the hardrock miners were so tough:

Watch Charlie Thorn explain how the region’s robust history is now represented in every mile of the Hardrock 100 course:

Civilization, Sprung

As the Hardrock 100 breathed its first breath in 1991, Silverton, Colorado’s hardrock mining took its last. That’s the year that the Mayflower Mill, located across the Animas River from the mouth of Arrastra Gulch, about two miles east of Silverton, shut its doors for the last time. (Aside: The Mayflower Mill is now a National Historic Landmark, owned by the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado, and is open for tours. It’s really cool.) In analyzing the history of San Juan Mountains mining and the economy, culture, and location into which this mining sprung and struggled to sustainably operate within, it’s frankly surprising and wholeheartedly fascinating that it lasted as long as it did.

1859 was the year prospector Charles Baker made his way to what’s now Silverton, first named Baker’s Park after him. According to the story, he located gold, went back into the world to tell others and tempt them to the San Juan Mountains, and started a small gold rush. This initial rush almost immediately stalled out because of the start of the U.S. Civil War.

Prospecting didn’t ramp up until another decade later, once the war ended, communities in the eastern U.S. began to recover, and the thought of seeking success mining in the American West began to creep into mind again. The Little Giant Mine, sitting on the north side of Arrastra Gulch and spitting distance from the Hardrock 100 course as it passes through the gulch’s base, one of the first of the region to be successful, was established in 1870, its ore assaying at values which, when spread upon the tongues of mining hopefuls, began another movement of prospectors into the region.

This push met opposition from the Ute tribe of Native Americans, as the San Juan Mountains were part of the Ute Reservation of southern Colorado. It wasn’t long, however, until the U.S. federal government entered into negotiation with Ute leaders to try and gain mining access to the mountains. In the 1873 Brunot Agreement, the Utes handed over 3.7 million acres to the government in exchange for some money and continued hunting rights to the mountains. What a deal?! The result, at least for those interested in the extraction of metals from the San Juans, was an opening of the proverbial exploratory floodgates. In the rush of it all, in 1874, the settlement of Baker’s Park became the town of Silverton, officially established and made the county seat—a title prestigiously regarded at the time.

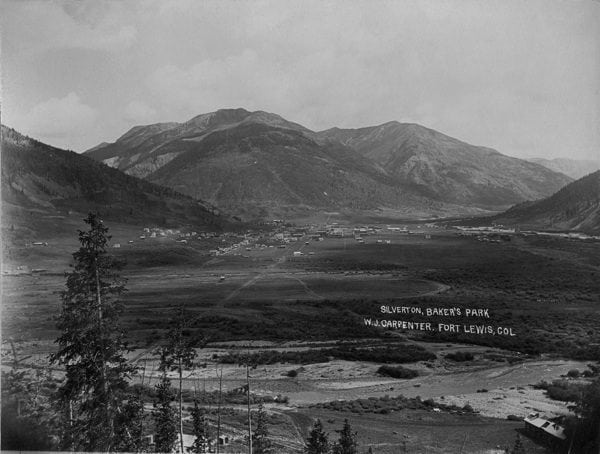

Looking northeast into Silverton, Colorado, in 1895. Image taken from the base of Sultan Mountain. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

As mines multiplied in the mountains around Silverton, so did the town build itself up as a mining support structure. Stores selling food, hardware stores, blacksmith shops, saloons, barber shops, a church, brothels, and many more businesses boomed and busted and boomed again—as mirrors to the mining boom-bust cycles—along the same dirt, gridded streets we find in town today. The San Juan Mountains gold and silver ‘rush,’ however, in comparison with other rushes of the American West, was a bit more tempered with profit margins and ore grades generally lower than those of the rushes in the Black Hills of South Dakota and the Sierra Nevada of California, as examples. As such, the Silverton boom-bust cycle was less severe, too.

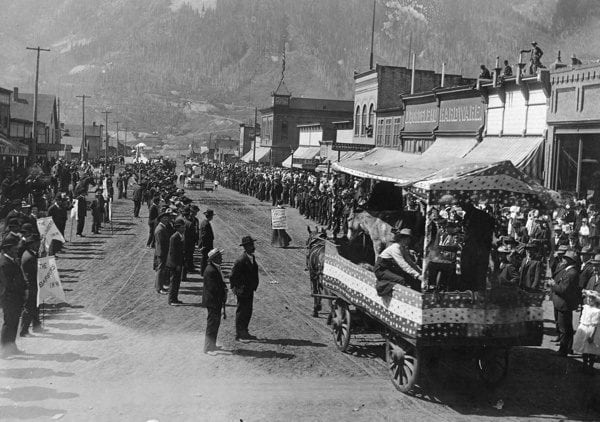

The 1908 Labor Day parade in Silverton, Colorado. Image taken looking west from 12th and Greene Streets. Float appears to be advertising a blacksmithing operation, while the woman walking in front of the float is a fortune teller. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

What was happening in Silverton was simultaneously happening in several other San Juan Mountains settlements. Lake City, on the east side of the range, was similarly incorporated in 1873, immediately following the Brunot Agreement. Ouray, on the north side of the San Juans, was incorporated in 1877, and Telluride, near the range’s western margin, followed in 1878. Together these four towns and the mines supported by them made up the mountain range’s four principal mining districts.

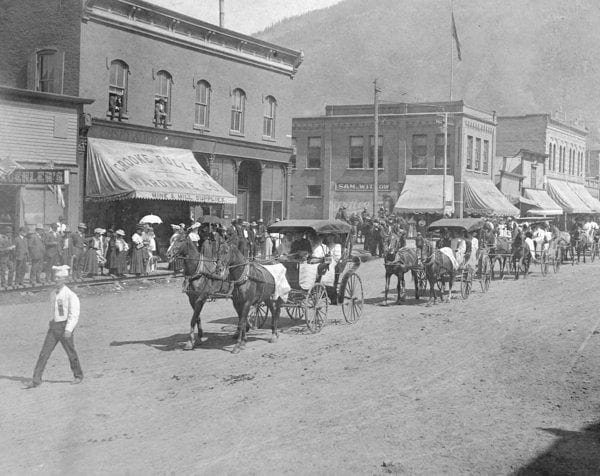

Another image from the 1908 Labor Day parade in Silverton, Colorado. Image taken looking east on Greene Street. Note the formal attire of Silverton’s inhabitants, and many women on the horse carriages and boardwalks. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

Silverton, Lake City, Ouray, and Telluride each have delightfully colorful, page-turning-ly interesting histories. At the turn of two centuries ago, each was a true outback town. Their gridded plats, when viewed on a map or from some bird’s-eye perch above town, square out in stark contrast to the steep and rocky landscape that makes up the balance of the San Juan Mountains. While the development of gridded streets was something of a city-planning trend at the time, it seems to a modern observer an intentional outpouring of that which is civilized into what must have back then been an incredibly isolated place to live and work.

Remnants of a hand-made wooden water pipe located on the Perimeter Trail above Ouray, Colorado. Image taken in 2015. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

With so much incredible Silverton history, it’s difficult to boil things down to a few hundred words! We should tell a few other stories, though. Silverton did not escape the lethal grip of the Spanish Influenza Pandemic, which circulated worldwide in 1918 and 1919. An estimated 10% of townspeople succumbed to the flu, with reports in the range of 130 to 150 casualties. According to locals, nearly everyone fell ill—it was only a matter of whether it made you sick for a few days or whether it was a lethal illness. So fast-moving and fast-killing was the pandemic in Silverton that it was not possible to individually process all the bodies. As such, Silverton’s Hillside Cemetery has a large mass grave in which many of those who died in the pandemic are buried and today memorialized. The mass grave is an eerie modern site and a reminder that, despite how tough the hardrockers were, they were not invincible.

While women were among the earliest groups of men prospecting—often accompanying their husbands—men and women generally held different roles in the San Juan Mountains outback. Men almost exclusively managed and worked within the mines. Sometimes you would see a woman who was married to a higher-level mine worker or manager living with her husband in managers’ quarters and working in service capacity at the mine. There are, however, a few unique stories of women who worked in positions typically saved for men in the remote mines, such as boardinghouse cooks. And several mines around the San Juan Mountains specifically prohibited the visitation of, ahem, single women. Brothels were popular in the developed towns of the San Juan Mountains, and that sort of ‘entertainment’ was often prohibited from taking place out at the mines.

In towns like Silverton, Lake City, Ouray, and Telluride, women held strong community roles as business owners—including the ownership of male-frequented businesses such as in-town boardinghouses for men, brothels, and saloons—church organizers, and more. With their husbands in the mountains for days at a time, townswomen were often the almost-exclusive keepers of the home, including parenting and the manual labor associated with home upkeep in a remote environment. If a family lived in one of the dozens of smaller mining towns scattered around the mountains, a woman’s life of maintaining her home came with even more significant physical labor. Multiple historic references seem to indicate that, though there were fewer women than men pioneering life in the San Juans, and though women held differing roles in work, and though women were not yet regarded as equals in mainstream America, they were equally respected in society out here.

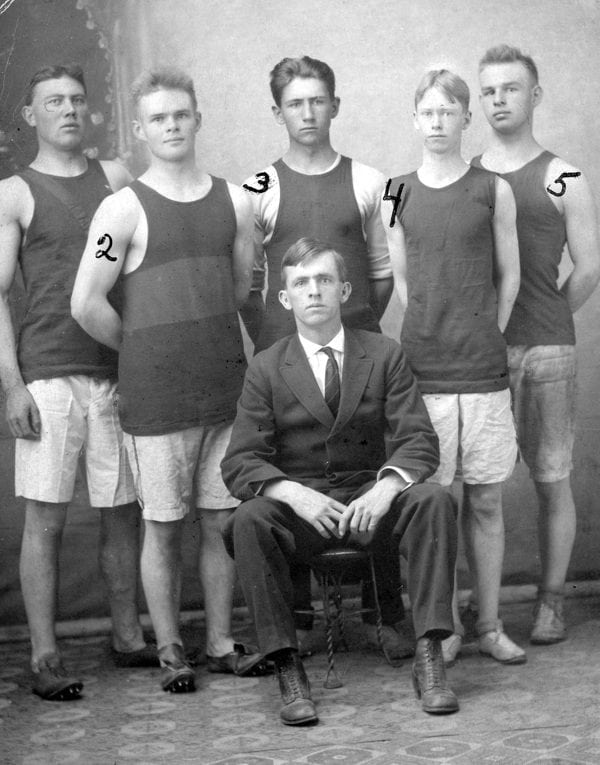

Silverton, Colorado’s first track team, in 1914. Left to right is: 1-Bob Schwenk, 2-Roy Brumfield, 3-Lester Kramer, 4-Billy Maguire, and 5-Carl Brumfield. The coach, Walker Williamson, is seated in front. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

San Juan Mountains Geologic Setting

“Don’t get too excited. The mining heyday here has long since come and gone,” says Rick Trujillo, a geologist and former miner who lives in Ouray, Colorado, and who helped design the original Hardrock course.

What he’s referring to are the larger-scale mining operations that once took place in the San Juan Mountains and that characterized about 120 years worth of life here, from the early 1870s to the early 1990s. He explains the primary materials mined, “Back then, it was lead, copper, and zinc. The metal with the greatest tonnage was zinc, but gold and silver were always there. Except for the Camp Bird Mine [near Ouray] was primarily a gold mine and so was the Gold King Mine near Silverton. And the Virginius Mine [by Ouray] was primarily a silver mine. But they all had lead, copper, and zinc, too.”

In this video, Rick Trujillo explains the complex geologic setting of the San Juan Mountains, and the reasons for which metals are found in the rocks here:

Gold and Silver: Heartmakers, Heartbreakers

If it was gold that initially drew prospectors to the San Juans, it was the silver, lead, copper, and zinc that allowed them to stay. And perhaps the senses of exploration and independence, too, offered by life in such a remote place. In historical documents, several miners have also said that strong camaraderie was present among mine workers, and that was a reason they liked their lives.

Rick Trujillo, who worked in several mines around the San Juans in the more modern mining era of the 1960s and 1970s, speaks to these relationships, “You like the camaraderie of the guys you worked with. Miners take care of their own. You may not like a particular person, but when they are in distress you go to their aid. You put all the politics and everything aside when you are underground. You put the bar fight aside when you’re underground. I miss that stuff. I miss that camaraderie.”

There may have been one more significant draw to hardrock mining: “It paid better than most professions,” laughs Rick Trujillo.

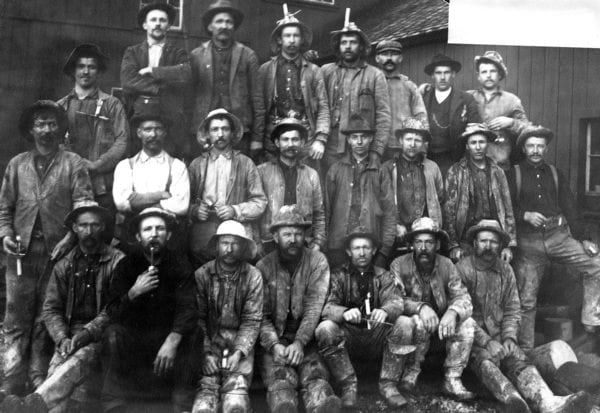

An unidentified group of miners outside an unknown mine in the San Juan Mountains. Note candles on some men’s hats for lighting. The man in the white shirt may have been a supervisor-type figure given his clean-looking appearance. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

To boil the complex art of historical hardrock mining into a ridiculously-too-simple set of steps, it went something like this:

- Prospecting hillsides for outcrops of metal-bearing rock;

- Staking a mineral-rights claim to an area of land as permitted by federal law;

- Exploring a claim via digging into the hardrock;

- Expanding a mine underground with tunnels, shafts, and other features to allow access to metal-bearing rock and create ways to remove it from underground;

- Milling the ore, or mechanically separating the valuable metals and the ‘waste rock,’ or tailings; and

- Smelting the ore, or chemically separating the different kinds of metals from the ore. (Occasionally, ore is of such a high grade that it skips the mechanical milling process and goes straight to smelting.)

All of the elements of this hardrock-mining process took place in the San Juan Mountains–the region was a self-contained entity in terms of having the resources to see the mining process through from start to finish. The finished products of the mining process were transported out of the mountains first by livestock, later by trains, and even later by trucks in order to be sold.

In these two videos, Rick Trujillo explains, first, some of the techniques that were used underground in hardrock mining, and second, the various kinds of mills that were used in the San Juan Mountains to process ore:

If a payout was expected with the quality and/or quantity of metal discovered, mines were established independent of how logistically challenging it was to do so. Underground mine shafts thousands of feet long, mine entrances located on vertical cliff faces, boardinghouses full of miners at 12,000 feet altitude and and higher, and years’ worth of building infrastructure to support a couple years’ worth of extraction: all of this was 100% standard operating procedure.

Some mines operated year-round, even though this region’s winters are robust. Additionally, and especially as the years went on, mines and mills established multiple work shifts to keep operations running 24 hours a day.

The Old Hundred Mine boardinghouse and upper tram terminal, in 2016, located on the west side of Galena Mountain, above Cunningham Gulch. The altitude is about 12,000 feet here, and when this was in operation, approximately 40 men worked and lived full time, year round. Silverton, Colorado is seen in the background. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

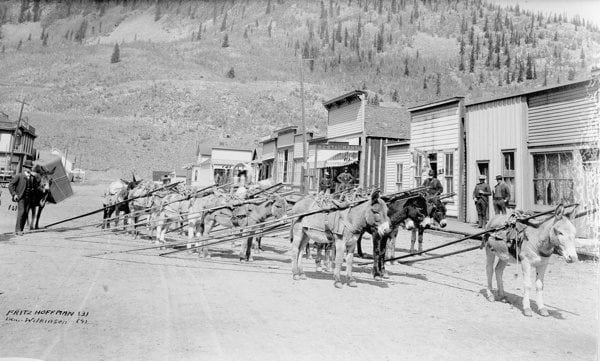

A pack train standing on 13th Street in Silverton, Colorado, in 1892, before setting out for a mine. Strapped to most of the livestock are rails, and one burro in the back left is carrying an ore car. Before the invention of aerial tramways, livestock were chiefly used to carry materials in and out of the mountains. Imagine the balancing act these burros enacted, dragging those rails up steep trails. Often, hundreds of livestock were used to support a single mine. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

Rick Trujillo explains, “Once upon a time, a lot of these mines were found at very high elevations, and the miners lived there. Trams were used to get the broken ore from the mines way up high down to mills, which were in more suitable, lower locations. The trams weren’t here at the very start–first it was just livestock. One of the very first trams was the Silver Lake tram. It went into Arrastra Gulch to Silver Lake, way up high. It’s not part of the [Hardrock 100] course but you run right under the old tram line. In fact, my dad and his brother were the last two guys to step off that tram from the Mayflower Mine in, I don’t know… 1963? 1966? I can’t be sure when the mine closed, but they were the last ones to step off the tram. The trams filled many purposes. They brought the ore down, and they brought supplies up. And they carried miners around, too.”

In 1906, an aerial tram connected the Gold King Mine and mill outside of Silverton, Colorado. Buckets 22 and 24 are shown, as well as four unidentified men. Aerial tramways were used to transport ore, building and mining materials, miners, food, and more up and down the mountains. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

Remnants of the aerial tram that connected the Buffalo Boy Mine in Rocky Gulch to the base of Cunningham Gulch outside Silverton, Colorado, in 2015. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

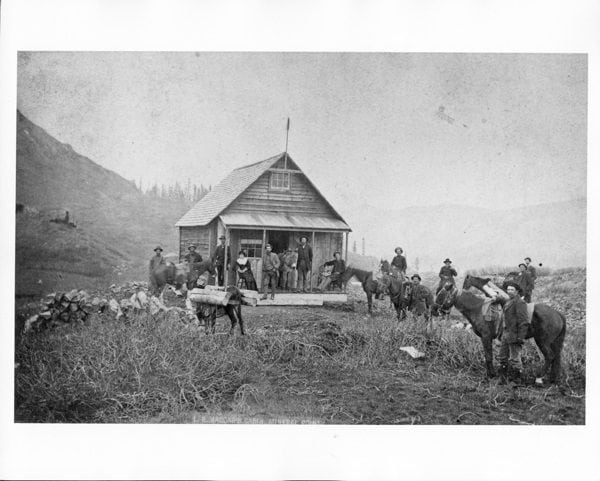

A cabin owned by L.R. Vaccar, located at Mineral Point in the San Juan Mountains, unknown year. Such homesteading was common in the San Juans. Given its location above treeline, it’s probable that this cabin was a three-season residence. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

“The Idarado Mine goes from 12,800 feet down to mill level at Telluride, at right about 9,000 feet elevation. I worked there. Up high in Black Bear Mine–I worked there as a nipper [apprentice] in 1968–I can vouch that there is something called permafrost in these mountains. There was frost on the walls. I was freezing all the time, even in summer. You go down to mill level, it was a pleasant temperature, 75 or 80 degrees [Fahrenheit]. Up high there’s definitely permafrost, I’ve been in it,” says Rick Trujillo about some of the underground-mining conditions.

He continues, “At 12,800 feet altitude, mining is hard work. Mining is always hard work. When you are working in temperatures close to freezing and you’re being sprayed with water, you are freezing. Miners are tough. You just get used to it.”

You can easily imagine that part and parcel to mining was risk, injury, and death. Few records were kept on San Juan Mountains mining mortality rates, but historic documents are chock-filled with stories of tragedy–avalanches killing winter miners, collapsed underground mine shafts, and more.

Rick Trujillo speaks to the hazards of mining in the 1960s and 1970s: “I really enjoyed it, I enjoyed going underground. But, sure, there are hazards in mining. There are hazards in anything. Nothing is safe. It’s safer than walking around Central Park in New York, though. I used to get a ‘powder headache’ from the nitroglycerin[, an explosive used in hardrock mining.] A powder headache goes to the back of your brain. I don’t get migraines but I imagine they are alike. I broke my back working at the Camp Bird Mine, crushed the third, fourth, and fifth lumbars. But I still couldn’t think of anything else when I was in the hospital.”

A mine adit located at the base of the climb to Little Giant Pass just above the Cunningham Gulch Aid Station. Hundreds of these can be identified by the observant traveler along the Hardrock 100 course. Image taken in 2015. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Mine Stories from the Hardrock Course

After years of visiting the mines and mining-related materials along the Hardrock 100 course and a couple months specifically researching them, we can safely say that we need much more time and cataloguing to fully understand the mining history to which the Hardrock 100 course connects us. Master’s thesis project in American history, anyone? While we can’t consider all the stories from along the Hardrock course, let’s dive deep into several of them. In consideration of the 2016 Hardrock 100’s clockwise direction of travel (the event reverse directions on its loop each year), we’ll travel in clockwise fashion around the course.

Putnam Basin Mine

The Putnam Basin Mine was a small mine located in Putnam Basin underneath the Hardrock 100 course. Once you have cleared treeline and you are making the sweeping climb through the tundra to the saddle at the basin’s head, you can spot wreckage underneath you. It’s clear this mine was accessed by Silverton’s Bear Creek Trail on what’s now the Hardrock 100 course, but not much is known except that gold that was extracted from it.

Bandora Mine

The Bandora Mine and its mill ruins come into view as you make the final descent to South Mineral Creek and the KT Aid Station at mile 11. Silver was struck here in 1890 and the rock of this drainage was worked on and off through 1940.

A machine artifact located below the Kamm Traverse and Ice Lakes Trail junction on the Hardrock 100 course, in 2016. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Ophir/Iron Springs Mining District

The Hardrock 100 course passes through the heart of this small but once ambitious and productive mining district as it drops through the bottom of and climbs out of Chapman Gulch, the gulch formed by the Howard Fork of the San Miguel River. Keen-eyed runners can spot from the course dozens of pieces of mining debris, adits, trails, and structures. Among the big-performer mines of this valley were the Carribeau and Carbonero Mines, located a bit down the gulch from but visible from parts of the Hardrock 100 course. Mining ramped up quickly in this gulch in 1878, and the road over Ophir Pass was initially used to transport ore to smelters in Silverton, until more local infrastructure for ore processing were established. Like much of the San Juans, this district’s mining peak was in the 1880s and 1890s, and the little village of Ophir supported 1,000-plus people and all the services one needed to live, work, and mine.

Fascinatingly, we found records that the a portion of the Carribeau Mine was sold on ebay in 2014 for $11,411 by a company called Gold Rush Expeditions, Inc. Written materials by the seller indicated that the purchase included 12.8 miles of underground tunnels, two accesses to those tunnels on the mine’s first and sixth levels, the long streak of tailings you can see on the hillside below the main mine entrance, and 22 above-ground acres and the materials on them.

The Blixt Road

Called the Oscar’s Pass Road today, it’s a 2.4-mile switchbacking route that climbs the north side of Chapman Gulch to Oscar’s Pass in 2,600-ish vertical feet. The Blixt Road was once a mining route connecting the Ophir Mining District with Bridal Veil Basin, which is over the hump of Oscar’s Pass and to its northwest, and beyond into La Junta Basin. Brothers Oscar, Gator, and Harry Blixt were sons of a Leadville, Colorado miner who purportedly came to Telluride around 1912 to work in mines outside of Telluride. The Blixt Road was built by Oscar, and the peak due west of Oscar’s Pass proper is Oscar’s Peak, also named for him.

Nellie Mine

The Nellie Mine ruins can be found in the upper reaches of Telluride’s Bear Creek drainage, a north-south drainage that empties into the heart of town. These ruins represent the leftovers of one of Telluride’s most successful mines.

What’s now called the Bear Creek and Wasatch Trails, used on the Hardrock 100 course, were originally created as a trail used for getting miners, supplies, and mined materials in and out of the Nellie Mine via foot and livestock.

Eventually aerial-tram systems were invented and brought to the San Juans, which made the transport of materials to and from the mines thousands of feet above towns, more efficient. A couple historic photographs and accounts describe a scene that played out on July 1 through 3, 1897, in downtown Telluride. During these three days, some 10,810 continuous feet of aerial-tram cable were strung out on the streets, estimated to weigh 17,000 pounds total. Eventually spools of the cable were strapped to approximately 65 mules, all connected in one train, and transported up the Bear Creek drainage for installation. Maddening logistics!

Liberty Bell Mine

Another of Telluride’s biggest-producing mines, the Liberty Bell Mine, was located high in the Cornet Creek drainage north of town, and originally accessed by the Liberty Bell Basin Trail, on which the Hardrock 100 now travels. Both gold and silver came out of Liberty Bell in abundance. So fruitful was the Liberty Bell in the San Juan Mountains mining heyday that it, along with many other successful mines around the range, operated year round. The San Juan Mountains are ridiculously avalanche-prone terrain, which in addition to winter’s other climactic challenges, introduced an elevated level of risk for miners. Avalanches, mostly called “slides” by miners back then, were unfortunately a common part of mining life.

On February 28, 1902, a large slide engulfed the Upper Liberty Bell Basin boardinghouse as well as other structures. Reportedly, the boardinghouse was knocked entirely off its perch in the basin. During rescue operations that day, two more large slides occurred, which caused more injury and death. The casualty tally was 19 men dead and 10 injured, a huge tragedy.

Smuggler-Union Mine

Standing on the south side of Virginius Pass, one looks south into Marshall Basin. Marshall Basin is the site of the first Telluride area mining claims, made by John Fallon and a partner, who may have been named Mr. Wightman, in 1875. Fallon’s was called the Sheridan Claim, and his partner’s the Union Claim.

The details of the earliest claims made in Marshall Basin are exemplary of the business shenanigans that were absolutely commonplace in San Juan Mountains mining. According to the story, Fallon and his partner staked their adjacent claims improperly. The following year they were beat on site by J. B. Ingram and two other men who identified the incorrect staking and essentially staked around the claims. Ingram’s claim was known as the Smuggler Claim. Eventually the Marshall Basin claims were consolidated into the Smuggler-Union Mine, which became one of Telluride’s most successful.

An incredible detail: since John Fallon was such an early prospector to what would eventually become the Telluride area but since it was totally undeveloped by white people at the time, he accessed the basin by what was described as a “keyhole” from the Ouray side of the mountains. Voila! Studying the ridgeline through which what we now call Virginius Pass cuts and seeing wonderfully few other possible passageways, and the fact that the pass is at the head of Marshall Basin, one can infer Virginius Pass may have been Fallon’s keyhole.

Revenue-Virginius Mine

While the Revenue-Virginius Mine might garner great gasps of awe for its improbable location in the northern, snowy shadow of the fear-inspiring Virginius Pass on the Hardrock 100 course, it is just one of dozens of mines perched in wicked locations in this mountain range. This mine has a long, ornate, financially successful, and, at other times, disastrous history perhaps even more worthy of our incredulity.

The mine was platted in 1876 by William Feland who called his claim of silver and gold the Virginius Lode, and purchased in 1880 by Albert Reynolds and John Maugham, who formed and operated the mine as the Caroline Mining Company under what seems like a go-big-or-go-home mentality.

The construction of the famous Revenue Tunnel, a 7,741-foot, angled, underground structure at the mine, began in 1888 and it took until 1893 for it to be completed. While mining tunnels were commonplace for accessing valuable metals underground, the Revenue Tunnel was among the first of its kind in its size, cost, and required support infrastructure. The tunnel was used to both access the mine’s silver- and gold-producing vein and to allow the ore to be lowered out of the mine at a lower altitude.

This Revenue Tunnel, which is reported to have cost $400,000 to create, along with equally aggressive surface development, proved to succeed in finding reward within great risk. By 1896, the onsite mill was processing a purported 300 tons of ore per day in search of predominantly silver and some gold. By 1904, a $300,000 profit was, shall we say, enjoyed. Phew!

Boardinghouses held 100-odd miners, and plumbing and electricity kept them warm and relatively content, all things considered, year round.

Reynolds retired in 1911, after seeing some $28 million worth of ore come out of the Virginius Lode. The mine remained in the Reynolds family for quite some time. In the 1920s, its mill burned down. In the 1940s, the mine shut down.

Like many of the more profitable mines around the San Juan Mountains, multiple attempts were made to reopen the mine over the decades between the 1940s and now, but volatile metal prices and low profit margins remain the governing factors of why these reopenings were brief.

In the recent history of 2011, Star Mining, a Denver, Colorado mining company, bought and reopened the Virginius Mine and went after things for a couple of years. In the few years it operated, the Mine Safety and Health Administration, the federal-government branch that regulates and enforces mine safety, reported a higher-than-average incidence of injuries and safety violations. This came to a tragic head on November 17, 2013, when two men were killed and 20 men injured via carbon-monoxide poisoning some 8,000 feet underground. Star Mining was eventually fined a bit over a million dollars for what was called by the government blatant safety violations that led to the miners’ deaths and injuries.

The approximately 1,100-acre mine was sold again in 2014 to Canadian company Fortune Minerals Limited. Work took place at the mine in 2015 but that company apparently defaulted financially and laid off 100-plus employees. Now, as of early 2016, discussions are apparently in the works to reopen the mine yet again. In June, 2016, when iRunFar visited Governor Basin, all was quiet at the Virginius Mine.

Camp Bird Mine

Oh boy, where do we start in describing the Camp Bird Mine? We have a little joke that helps give perspective on the significance of this mine. While there is the Million Dollar Highway, Highway 550 connecting Ouray and Silverton, we think that the Camp Bird Road, which stretches from above Ouray to Camp Bird Mine and on which the Hardrock 100 course travels, could be nicknamed the Billion Dollar Highway. In modern U.S. dollars, the Camp Bird Mine has produced more than $1.5 billion in gold and has been one of the largest gold mines in the U.S.

Thomas F. Walsh, born in Ireland and an American immigrant, first immersed himself in the Black Hills of South Dakota gold rush in the 1870s. There he accumulated a goodly fortune off the trade of equipment and supplies mining operations needed to do business and the sundries miners needed and wanted to live. After that, he hit up Leadville, Colorado and ran the Grand Central Hotel.

He finally found himself in the San Juans, running a smelter in Silverton first and living in Ouray second. According to the story, he started spending a lot of time in the mountains above Ouray, methodically prospecting. In 1896, he purchased old claims in upper Canyon Creek that had previously been worked since 1877 for silver, zinc, and other metals and that he found to be extremely high in gold content.

The development of the mine went fast and furious, with a mill, aerial tramway, boardinghouses, underground tunnels to access more rock, and other infrastructure going in within a couple years and the gold assaying out at supremely high prices. Notably, the Camp Bird Mine during this time was known as an upscale mine to live and work at, with shorter, eight-hour workdays and boardinghouse conditions bordering on the luxurious for the time.

Thomas Walsh sold Camp Bird Mine to a British company who named itself Camp Bird, LLC in 1902 for a reported $6 million. That company brought the mine into its peak of gold production, and from 1902 to 1910, it was the second-largest gold mine in Colorado.

Until roughly 1990, Camp Bird Mine opened and closed a number of times, underwent extensive growth and rebuilding, and then closed for a while that year. In 2013, Caldera Mineral Resources, LLC reopened the Camp Bird Mine but apparently couldn’t make it float. It was listed as abandoned in 2014.

Watch Rick Trujillo talk about the Camp Bird and Virginius Mines in animated detail:

Grizzly Bear Mine

Hardrock 100 runners surely agree that the Bear Creek National Recreation Trail outside of Ouray, Colorado is a thing of engineering beauty. Constructed in the 1870s by hand and with explosives to build a horizontal shelf into the near-vertical walls of Bear Creek Canyon for the purpose of hauling in mining supplies and out the fruits of mining labor, largely by livestock, to the Grizzly Bear Mine. As we understand it, a claim was made in 1875, what would become Gizzly Bear, and $1 million worth of ore was extracted in the 30 years to follow.

Here Rick Trujillo explains how the Bear Creek Trail in Ouray was constructed:

The Grizzly Bear Mine, like many San Juan Mountains mines, did not survive World War I. After the war, the mine was purchased by Lars Pilker and John Zanett, and they experienced extended trouble in trying to make the mine work. Eventually, ownership fell to John Zanett’s son, Fred Zanett, who expanded the mine to the north by making additional claims in the 1970s. Their idea was to drive a long tunnel through the mountain between Bear Creek Canyon and the Amphitheater, a glacier-carved cirque located above and just east of Ouray proper, so that they could remove ore via another route besides the precarious Bear Creek Trail. Started in 1978 and finished some 12 years later, the Zanett Tunnel is 8,500 feet long.

Work at the mine continued until 2000, at which it was reported as abandoned. In 1999, local Joseph Mattivi was crushed and killed by heavy machinery at the mine. Joe was the brother of the current Ouray sheriff, Dominic Mattivi.

Yellow Jacket Mine

A primarily lead and secondarily zinc mine believed to have reached peak production around 1915, it’s located just above the 11,000-foot-altitude mark on the Bear Creek Trail above Ouray, Colorado. A 1917 historic document reported that the Yellow Jacket’s manager purchased materials to build an on-site stamp mill and stated there was a couple years worth of material to process at that point. An early 1919 publication reported that the Yellow Jacket’s mill was completed.

Remnants of machinery and the stamp mill of Yellow Jacket Mine, above Ouray, Colorado, in 2016. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Says Rick Trujillo, “Bottom line is, there’s almost nothing there. The Yellow Jacket Mine is a classic example of building a mill in the middle of nowhere and going to look for a mine. It never milled a damn thing.”

Ore not living up to expectations, direct fraud, and rapidly fluctuating metal market values are just a few of the potential causes for the Yellow Jacket Mine not amounting to much. These situations were not uncommon in San Juan Mountains mining.

Animas Forks

To the west of Engineer Pass Road, where the North and West Forks of the Animas River meet, lays the Animas Forks town site, a town with a short-but-sweet lifespan. Animas Forks was settled first in 1883 and quickly developed into a mining-support hub for the mines immediately surrounding town, becoming home to at least 450 people. The town was essentially abandoned around the Depression Era. Multiple phases of restoration have taken place, and in 2011, it was placed onto the National Register of Historic Places.

Animas Forks, now a ghost town, located along the Hardrock 100 course outside of Silverton, Colorado. Image taken during 2015 race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

A marker noting the Lulu Lode, near the Hardrock 100 course in Grouse Gulch, outside of Silverton, Colorado. 1883 historic documents note considerably high-quality silver, lead, copper, and a few other metals coming out of the Lulu Mine. Image taken in 2016. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Sherman

Sherman was another town site that operated in support of several surrounding mines, namely the Black Wonder Mine and mill located on the hill north of town, which processed mostly silver. Sherman was established in 1877 and grew to 350-ish people by the mid-1880s, reflecting the boom of local silver mining. A decade later Sherman was effectively empty as silver prices dropped, the surrounding mines no longer operated, and miners moved elsewhere.

Intersection Mine

While Maggie Gulch outside of Silverton, Colorado contains several metal-bearing claims that were worked in the late 1800s and early 1900s, perhaps the most relevant to the Hardrock 100 was the Intersection Mine, whose ruins are located precisely where the event’s Maggie Gulch Aid Station is. Purportedly named because two significant rock veins intersect there, at least one modern reference seems to misplace the Intersection in the adjacent Minnie Gulch. However, a number of historical documents we located dated between the years 1910 and 1917 indicated the in-progress operations of the Intersection Mine in Maggie Gulch as a small-scale but profitable mine and stamp mill for gold and silver on what was originally staked as the Iron Mask Claim. The Intersection Mine and the other mines represented by the ruins you see dotting the hillsides of Maggie Gulch are perhaps the mining Davids to the Goliaths we see elsewhere on the course, like at the Revenue-Virginius and Camp Bird Mines.

The Intersection Mine’s stamp mill, located at the Maggie Gulch Aid Station on the Hardrock 100 course outside of Silverton, Colorado, in 2016. The stamps–the large, vertical, metal rods–are still in place. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

The upper tram terminal at the Buffalo Boy Mine in Rocky Gulch, outside of Silverton, Colorado, photographed in 2012. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Stony Pass Road

The Stony Pass Road, once a trail for foot traffic and livestock, later converted for horse and wagon use, and eventually for automobiles, was the way that the first prospectors made their way into the San Juan Mountains in the 1850s and 1860s. The 12,592-foot pass, shouldered by the 13,000-foot-plus Buffalo Boy Ridge to its east and Green Mountain to its west, yields gently enough to have let thousands of years of traffic through, but certainly not without difficulty and misadventure over the years. Perhaps we feel some of this challenge as we cross Stony Pass some 86 miles into the clockwise direction of the Hardrock 100?

One of the stories that will allow Stony Pass to live in fame—or is it infamy?—took place on August 27, 1910, when Louis G. Wyman, Sr. and his party navigated the first car over Stony Pass, down to Silverton, and into the San Juan Mountains. The car was a Croxton-Keeton ‘French type’ touring car. The Croxton-Keeton Motor Company was a short-lived entity that produced some 1,100-odd cars in the early auto-manufacturing days. Though the car was advertised for its sturdiness, reliability, and features made for the primitive road surfaces of the time, it was no match for Stony Pass and required livestock assistance over the road’s heinous bits.

Wyman seems a fascinating fellow we all would have liked to meet, who came as a mining prospector in 1876, in the middle of the early San Juan Mountains rush. He shortly saw the challenges of mining, tried a mining-materials freighting business, and eventually settled into real estate, building Silverton’s historic Wyman Hotel in 1902.

In 1910, the automobile was still something of a spectacle, and definitely a sign of wealth. However impractical it was to get a car into Silverton and the San Juans, it was perhaps an effort that Wyman saw as symbol of social and economic advancement in what was still a pretty remote mining town.

Image of the first automobile arriving to the San Juan Mountains over Stony Pass outside of Silverton, Colorado, on August 27, 1910. The car is a Croxton-Keeton touring car, and the ‘stunt’ was planned by Louis G. Wyman, Sr., owner of Silverton’s Wyman Hotel and a San Juan County, Colorado Commissioner at the time. Obviously the car needed a little assistance over the pass. Pictured left to right are Louis W. Wyman, Jr., Eugene Mechling, Louis G. Wyman, Sr., David L. Mechling, and the unidentified driver of a county horse team. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

Shenandoah and North Star Mines

As you travel in the Hardrock 100’s clockwise direction and enter into its last miles, you might not be lucid enough to notice the adits, tram wires, and other assorted mining debris on the Little Giant climb, in Dives Basin, and on the flanks of Little Giant Peak as you ascend out the west side of Cunningham Gulch. Historical notes record numerous claims in this vicinity, with the earliest being the Shenandoah Mine in the bottom of Dives Basin and the North Star Mine at the very head of the Dives Basin, not far from the top of Little Giant Peak on its southeast side, which were worked for silver and gold.

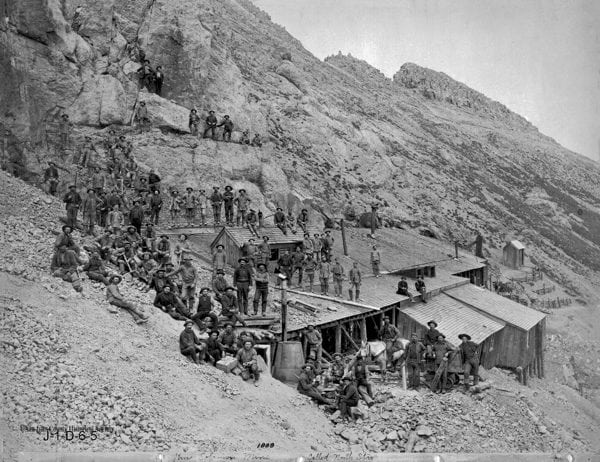

An 1888 photo of the North Star Mine, located on the southeast face of Little Giant Peak above Dives Basin outside of Silverton, Colorado. An ore car is shown at the lower right, likely where ore was brought out of the mountain and offloaded onto livestock for transport down the mountain. It is thought that ore from this mine was carried on livestock across what’s now called Little Giant Pass on the Hardrock 100 course, and down Little Giant Basin to Arrastra Gulch. What’s now called Little Giant Pass should be out of view of the lower right part of the photo. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

Though reports vary a bit, it seems that on March 17, 1906, an avalanche occurred in Dives Basin, killing 12 men at a boardinghouse located there. It seems this was one of multiple snow slides which occurred in the surrounding area that day and killed 18 to 20 miners and destroyed significant quantities of mining equipment. This is a grim but all-too-frequent tale of life lost while living and working high in the San Juan Mountains.

‘Historic trash’ located in Dives Basin, a hanging valley on the west side of Cunningham Gulch and through which the Hardrock 100 course passes, in 2015. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Little Giant Mine

The Little Giant Mine ruins are located in the heart of Arrastra Gulch outside of Silverton, Colorado. It was one of the first successful mines in the San Juan Mountains, beginning around 1870. You might recall that the Brunot Agreement between the federal government and the Ute Native Americans wasn’t signed until 1873, meaning that the first prospectors to claim and work the Little Giant Mine were doing so in discordance with federal law. This apparently did not stop the Little Giant Mining Company from setting up both a mine and a mill to process material, making the company $12,000 in 1873.

Photo taken in 1888 of the ore transfer site in Arrastra Gulch for materials coming from the North Star Mine and other claims on and near Little Giant Peak. Here, ore would have been transferred from the backs of livestock to wagons and transported further downhill to a mill. The Hardrock 100 course passes below this site in Arrastra Gulch. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

The Big Giant Mine mill and upper tram terminal in Little Giant Basin, outside of Silverton, Colorado, during the 2015 race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Sharing the Lode

Regardless of how much we are aware, or not—we all know that the Hardrock 100 course is well able to fully vacate our minds from our bodies—we runners are intrinsically and tangibly connected to the hardrock miners who preceded us. We walk where they walked. We crawl where they crawled. We stand on the same ridgelines they stood. We gaze at the same views. We pass the places they pounded hammers and turned jacks, where they slept and ate, along the same trails where they coaxed burdened livestock, and through the places where some of them died.

1936 Labor Day celebrations in progress–apparently a water fight–on Greene Street in Silverton, Colorado. Photo courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Society of Silverton, Colorado.

We probably possess intangible connections with the hardrock miners, too. We are all perhaps moved to see wild places, to experience the camaraderie of working with groups on the same mission, to chase our passions, and to work hard.

Reasons to be. Arrastra Gulch on the Hardrock 100 course, during the 2015 race. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

These mountains possess some 120 years of mining history, and now two-and-a-half decades of accumulated stories by the women and men who’ve created, organized, and participated in the Hardrock 100. Two stories, in effect, now intertwined into one. Our own lode, if you will, once carried on the shoulders of those who’ve preceded us, now carried by us. To where are we carrying our shared history? What kind of hardrocking, hard-working, big-dreaming, bigger-scheming individuals are yet to enter this story?

Charlie Thorn explains how the Hardrock 100 intertwines the past, present, and future:

It seems that our story has a fighting chance, too.

Notes to Readers

- All photos copyrighted to the San Juan County Historical Society in Silverton, Colorado may not be downloaded or reused without the permission of the society. Contact them at 970-387-5838.

- While we have tried to conglomerate a goodly volume of information connecting the Hardrock 100 course to the region’s hardrock-mining history, we consider this article a work in progress. We hope to expand it as more relevant information is unearthed. Do you have a story or information not covered here yet? Please leave us a comment or contact us and we will add it to the article. We know there are endless relevant and fascinating stories still out there!

- Find an inaccuracy? Please contact us and let us know. We have endeavored to report with accuracy and precision, but we know that plying stories from multiple historic sources and about situations with little documentation introduces room for error. Help us grow this project! Thank you!

Sources and Resources

We used the following sources to compose this article, and we encourage you to explore them, too, to continue learning the San Juan Mountains hardrock story!

- A Brief History of Silverton, 2003, Duane A. Smith.

- Charlie Thorn in-person interview, July, 2016, Silverton, Colorado.

- Fifteenth Biennial Report Issued by the Bureau of Mines of the State of Colorado, 1917 and 1918, Fred Carroll.

- Geology and Ore Deposits of the South Silverton Mining Area, San Juan County, Colorado, 1963, David J. Varnes.

- History, Geology, and Environmental Setting of Selected Mines Near Ophir, Uncompahgre National Forest, San Miguel County, Colorado, 2001, John Neubert and Robert H. Wood II., Colorado Geological Survey Department of Natural Resources.

- “History of the Revenue Mine,” February 22, 2013, Don Paulson, Ouray County Plaindealer.

- Index to the Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-Seventh Congress, 1882 to 1883, Government Printing Office.

- Mayflower Mill self-guided tour, June, 2016, Silverton, Colorado.

- Mines and Minerals, August 1910 to July 1911, Volume 31.

- Mines Around Silverton, 2015, Karen A. Vendl and Mark A. Vendl with the San Juan County Historical Society.

- Mining in Colorado: A History of Discovery, Development and Production, 1926, Charles W. Henderson, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 138.

- Mining the Hardrock in the Silverton San Juans: A Sense of Place, a Sense, 1996, John Marshall with Zeke Zanoni.

- Ouray, Colorado’s Official Visitor’s Guide, 2011.

- Our Backyard, June, 2016, Volume 11, Issue 2, published by The Nickel in Grand Junction, Colorado.

- Rick Trujillo in-person interview, July, 2016, Ouray, Colorado.

- San Juan Historical Society Museum self-guided tours, June and July, 2016, Silverton, Colorado.

- “St. Patrick’s Disaster of 1906,” March 17, 2012, Staff Writer, Durango Herald.

- Telluride, 2006, Elizabeth Barbour.

- Telluride: From Pick to Powder, 1979, Richard L. Fetter and Suzanne C. Fetter.

- The Engineering Magazine: An Industrial Review, October 1896 to March 1897, Volume 12.

- The Engineering and Mining Journal, 1897, Volume 63.

- The Engineering and Mining Journal, January 1 to June 30, 1919, Volume 107, Number 2.

- The Salt Lake Mining Review, April 15, 1917, Volume 19, Number 1.

- “The History and Minerals of the Grizzly Bear Mine, Ouray, Colorado,” November 11 to 12, 1995, New Mexico Mineral Symposium, Barbara Muntyan.

- The Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run Runner’s Manual Course Description, 2016, John Cappis with input from Charlie Thorn.

- Walking Silverton: History, Sights, and Stories, 2014, Beverly Rich with photographs by Casey Carroll.

- www.mininghistoryassociation.org

- www.sjindependent.org