[Editor’s Note: On September 17, 2022, Hannah Green completed the Sangre de Cristo Traverse, setting a women’s unsupported fastest known time and becoming one of the few people to finish the challenge, which extends some 110-ish miles over 77 peaks. Below is her account of 5 days, 14 hours, and 58 minutes on this spectacular route.]

11:00 p.m. Midnight. 12:30 a.m. 1:00 a.m. 1:30 a.m. Finally, my alarm sounded at 2:00 a.m. I made some coffee and lay in my truck, listening to the stillness of the early morning hours. It was warm in the valley. Slowly the coffee kicked in and I got dressed, double and triple checking my pack for odds and ends. I was ready. I shouldered the pack, walked a few feet over to the highway, and started my inReach tracking.

Part of me was having déjà vu — this was my fourth time starting the Sangres Traverse. But the other part of me felt more relaxed and prepared than I had ever been. I was also starting at least three hours earlier than any other time, which seemed like somewhat of a miracle considering an “alpine start” for me is anything before noon.

The Sangres Traverse is a burly ridgeline linkup running along the spine of the Northern Sangre de Cristo Range in Colorado. The ridge boasts over 77 peaks, five fourteeners, two of the “classic” fourteener traverses (including reversing the Crestone Traverse going Needle to Peak), and many other lower fifth-class scrambling sections. At over 55,000 feet of elevation gain (depending on all the summits and drop downs to get water) and roughly 110-ish miles, the route is stout.

There are some variations, but I followed Justin Simoni’s, going highway to highway, taking the southwest ridge up Little Bear Peak, and summiting some peaks that Nick Clark and Cam Cross left out of their self-supported attempt. I didn’t summit Milwaukee Peak like Justin, because it’s a little bit of an outlier and the weather had me anxious to get onto the Crestones. I went solo and unsupported like Justin and Ty Smith (who holds the overall fastest known time), carrying all my food and gear from the start.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 1

I picked my way through the piñon and juniper lit by the just-past-full moon. Just as I gained the southwest ridge of Little Bear Peak the sky began to lighten. I slowly worked my way up, very much feeling the weight of six days of food and four liters of water … along with my fastpack gear. I saw a couple of bighorns floating through the sunrise, a good omen, I thought. Eventually, I made it over the south summit of Little Bear to the actual peak.

A couple of young guys were up there, and I headed out on the traverse ahead of them. Remembering there were some areas where you weave around blocks, I immediately got off route. I have a tendency once I’ve done something a few times to remember certain turns, but I always turn too early. I regained the ridge behind the guys. They were stoked to be scrambling such fun terrain and in little sandals no less.

Turns out though, sandals are slower than a heavy pack and they eventually let me scoot by. I made it to Blanca Peak, ate some food, took some photos, and then headed toward Ellingwood Point. I again caught up to another group of dudes who inquired about what I was doing, given the sleeping pad strapped to my pack. I told them I had a long way to go still.

I made it off Ellingwood through the last technical stretch for the day but given my early start, I felt like I was moving well. I rolled through the ridgeline descending off California Peak to a herd of bighorn sheep. I’ve always hoped that in another lifetime I’ll come back as a bighorn sheep scaling big mountains and deep desert canyons.

As I neared the tundra slopes below Carbonate Mountain around sunset, I saw some hunters out wandering around. They were surprised to see another human out there. They also assured me the spring I was hoping to fill up at was still flowing. Normally off of Carbonate, you strike a lovely trail, some of the only and nicest on the whole traverse, but a windstorm had obliterated it with downed trees. There’s nothing like crawling over logs when you could be on buttery singletrack.

I quickly refilled all my water and put on my headlamp. I crossed Mosca Pass amongst the ruckus of some RV generators, went up the hill to the old communications tower, and then landed onto the faint trail that begins the Mount Zwischen ridgeline. I hiked until about 10:00 p.m. and found a nice, flat spot to set up camp. I didn’t realize how tired I was until I lay down and immediately fell asleep.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 2

My alarm sounded at 3:30 a.m., but I snoozed it for another hour before forcing my eyes to open. I didn’t bring a stove to lighten my load, so I stirred up some cold instant coffee and sipped it slowly.

Packing up was quicker than most trips because I had the bare essentials. I finally stood up, stiff and sore, and pulled the tent stakes. I had about an hour of darkness until a brilliant, red, smoky sunrise started glowing to the east.

I made quick work of the downed trees, knowing where to skirt them now after having gone through here so many times before. Zwischen passed uneventfully and I finally hit Medano Pass. I ate lunch and filled up with water one last time before climbing back above treeline. Some clouds were forming and distant rain fell on the horizon.

At Music Pass the first raindrops hit me, and I quickly pulled on my rain gear and headed up the steep slopes to Marble Mountain. The wind kicked up and the curtains of rain and graupel started. It certainly wasn’t warm either. I was hoping to get through Broken Hand Peak in the dark, but the wind and rain had me worried, so I bailed down into a basin just after Marble to camp.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 3

Sunrise the next morning was beautiful. Big clouds shrouding the peaks with hints of pink and orange, but also the clouds were sobering knowing I was heading into the most technical section of the traverse.

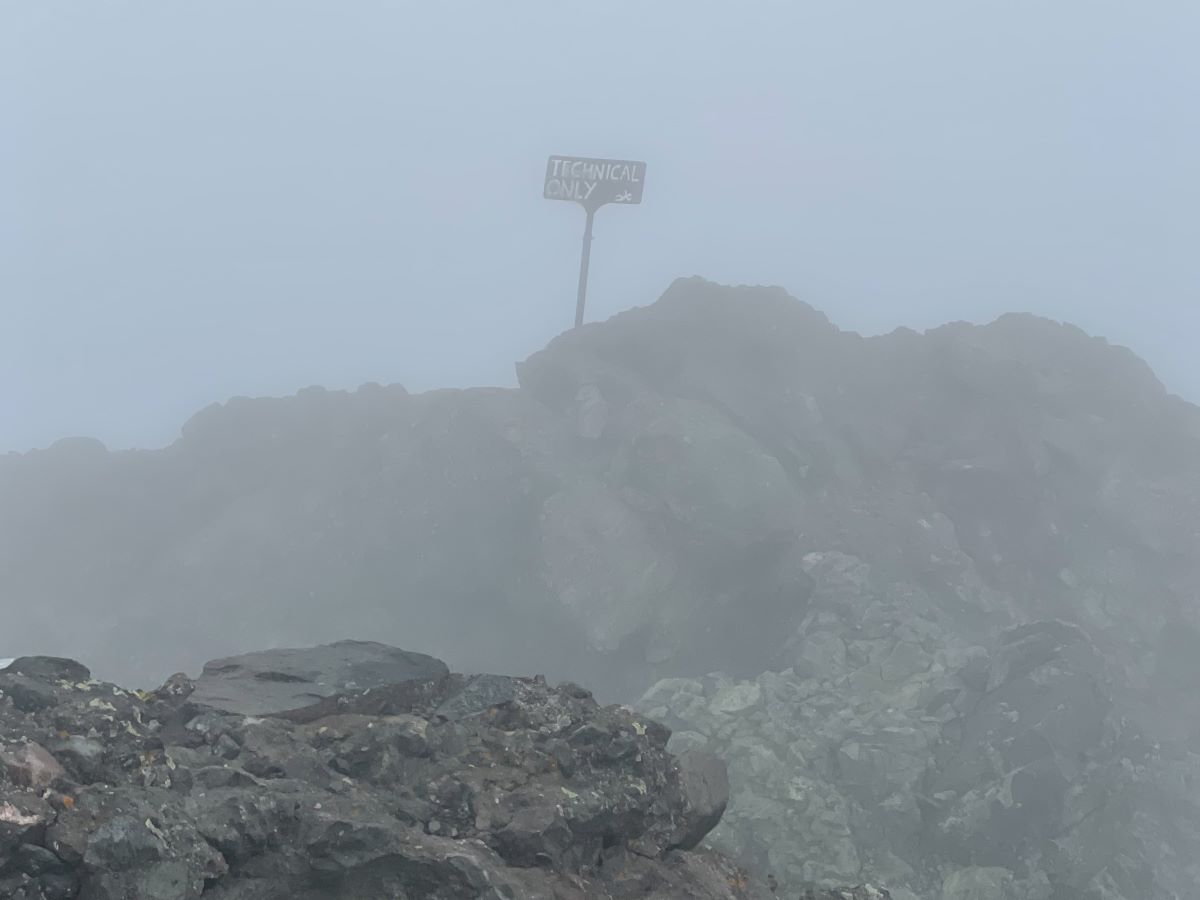

I crawled through Broken Hand, wasting precious time with some route-finding errors, but finally, I was heading up Crestone Needle. Occasionally, a pocket of clouds would open up and I could see a bit of the basin or distant peak, but for the most part, visibility was down to about 100 feet. I reached the summit and frantically set up my tent as hail pelted me.

I crawled in and waited for about an hour for the wind to dry the rock enough to downclimb the headwall. As I started down, my nerves were pounding. I took my time making sure my handholds were strong in case my wet shoes slipped. Made it down, phew! Now onto Crestone Needle. I literally saddled the rock and shimmied across. Now onto the bulge.

Rather than dangle my feet over the Class 5.2-rated chockstone, I chose to sneak around to climber’s left, but the damn wet rock. I found two good hand holds and basically slid my feet down as far they could until they stuck and I could just jump off easily. Made it again, phew!

Fortunately, the cairns for the rest of the traverse to Crestone Peak were just barely visible in the fog. I made it to the top of the Red Gully and gulped. The other side, my exit, was dusted with snow. I dropped my pack, hiked up to summit Crestone Peak, and hurried back down, anxious to get off these peaks. I took a deep breath and started down the cold, north-facing chute. I followed a rib of rock to stay out of the snow for a second but knew I had to get in the snow soon.

I skirted left for a moment, where the Crestone Conglomerate met some terribly crumbling shale, and I quickly kicked off a massive rock. Spooked, I skirted back to the more solid conglomerate. I kept contouring, thinking I could stay on the solid rock and hit the route that skirted the cliffs, but again I was way too high. Surrounded by nothing but wet rock, I went up, down, and around, zig-zagging and traversing faces with tiny, smooth holds.

A bit panicked that I was not only stuck but that at any moment I could slip, my mind worked hard as I evaluated each possible way down as well as its consequence. Eventually, I committed to some sketchy moves to get into a narrow gully that I could chimney down. Finally, I saw the cairn I was looking for and was back on track. I looked back up briefly at where I had been, the jagged cliffs soaring ominously in the fog.

The Crestones are infamous for their danger. It seems like every year someone falls from them. When dry and sunny though, they are some of the funnest scrambling, the conglomerate producing perfect solid places for your feet and hands. Humbling and harrowing, I was thankful to be leaving them behind for now.

As I hiked the tundra slope toward Obstruction Peak, the clouds broke. The evening sun flowed yellow through the mist, and I could finally see the sun-filled valley below. While the day was treacherous and taxing, I felt very grateful to experience the mountains in such rare conditions.

Before dropping off the peak, I glanced back at the Crestones, which still wore their shroud of clouds. Completely exhausted mentally from the day of such tedious moving, I decided continuing on the final bit of technical terrain in the dark was too much. I bailed down to some tundra protected in the basin and set up camp as the light faded. I was glad to be safe and in the familiar basin that felt like home. I slept well knowing the weather was supposed to improve tomorrow.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 4

4:30 a.m. again, my alarm sounded. I sipped my cold coffee and started moving at the first hint of light around 6 a.m. I gained the ridge at sunrise and was greeted with maybe the most spectacular light I’ve seen in a while. The clouds turned brilliant shades of pink and orange, giving the illusion that the mountains were on fire. The sun felt so energizing too after the previous day.

I started on the ridge, but quickly the clouds dropped and the wind blew hard. I slipped on a couple of rocks and realized they were starting to freeze. Within a few minutes, they and all the tundra were covered in rime ice. Ugh, I thought, This isn’t fun.

I gingerly made my way along the ridge, finally through the last of the scrambling, I climbed up and up to the summit of Mount Adams. As if it knew I was on top, the sun broke through a pocket of clouds. And just as quickly as the clouds blew in, they disappeared. I reveled in the heat of the sun.

I continued on the ridge. I was halfway through the traverse now and my legs could feel it. I’d hike a few steps and stop to let my heart and lungs catch up. Climbing Comanche Peak, I noticed another dark mass of clouds heading my way. Relentless! Suddenly the thunder boomed and snow began to fly, I found myself beelining it down to treeline.

I told myself I’d just set up camp and make a campfire to warm up until it passed. Right as I reached the first tree, I looked up. The veil of weather was thinning and I could already see the blue behind. I burst into tears, momentarily flustered as I turned around to head back up the thousand or so feet I had descended. A constant beat down out here!

Fortunately, the rest of the day was clear. I dropped off Hermit Pass at sunset to get some water and decided to take advantage of the clear skies and hike into the night. I made it to a flat, protected spot out of the wind around 10 p.m. and decided to pitch my tent.

As soon as I laid down though I could feel my knee throbbing. It had been hurting the whole time, but it wasn’t until I stopped for the day that I could feel the deep pain. I lay there for a while then finally took some ibuprofen, which let me sleep.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 5

I was up hiking again around 5:30 a.m. The sky was clear, but the wind howled and was strong enough that I could lean into it without falling.

I trudged along and after getting knocked over by the wind (while putting a sizeable gash in my knee), I finally reached tree cover below Nipple Mountain, the best-named and windiest summit of the traverse.

I reached Hayden Pass around 6:30 p.m. and was able to get down to some water and back up to the pass before nightfall. After getting battered by the wind all day, I decided to camp in the warmth and protection of the trees.

Sangre de Cristo Traverse: Day 6

I slept well and my alarm went off again at 4:30 a.m. The last day, I told myself. I skirted the leeward side of the ridge as I climbed through the trees. Eventually, I had to face the wind and when I popped up into it, I was so relieved it wasn’t the gale-force breeze of yesterday.

The sun rose and a dramatic shadow of the ridge cast itself to the west. Soft pinks illuminated the rocks and I realized for the first time since I started that I was actually going to finish the traverse this time.

I crawled my way up the remaining peaks, my body running closer to empty each climb, finally walking to the anticlimactic summit of Methodist Mountain — replete with its terrible name and host of cellphone towers. I was now roughly nine miles from the end. I headed down the dirt road. I called my dad and sister to let them know I’d be finishing.

I called a hotel to book a room, and I Googled the nearest restaurant to where I would finish. I talked to a good friend who was psyched to see me happy even though the pain in my knees had me hobbling. I hit pavement and finally, I reached the intersection of Highway 50 in Salida, Colorado, immediately turning into the restaurant on the corner.

Final Thoughts

It took a little over five-and-half days to complete the Sangre de Cristo Traverse, but this effort was four years in the making. I had poured everything into this ridgeline. Even the last relationship I was in was formed from a mutual love for the spine connecting these peaks together, a relationship that also left me tattered for too long but more determined than ever to make my own memories here.

I had fallen in love with these mountains before him and would love them even more after him. Something that proved true yet again in life is that the mountains will always be there, as people come and go in our lives and our bodies age, the hills will always be there when we need them. I look forward to slower trips in the Sangres, poking around the hundreds of side drainages, and camping at the beautiful lakes I’ve marveled at from above.

This is not the end of getting to know this place. Really it’s just a new chapter in the relationship, one that feels stronger and deeper than the years before.

Call for Comments

- Have you been to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains? What were your impressions of them?

- Is there a route that’s as meaningful for you as this one is for the author?