We are back with another edition of Running on Science’s Fact or Fiction, the occasional myth-busting version of our column.

In this sixth edition, we’ll tackle three more interesting tidbits you’ve likely overheard in the trailhead parking lot or on the trail. We utilize our best understanding of the current scientific literature to decide if these factoids are fact, fiction, or something in between.

Fact or Fiction: “Carbonated water isn’t as hydrating.”

Unless I’m really thirsty, I don’t really love water. Maybe you’re like me and, if so, we know that keeping ourselves adequately hydrated is a daily struggle.

I’ve found ways to trick myself into getting in that extra glass here and there. Often that means turning to a little flavoring, part of an electrolyte tab, or an herbal tea. And as the weather warms, what about that sneaky 12-pack of bubbly water I leave in my car for a post-run refreshment? I’ve definitely wondered out loud with running friends, “This can’t be as hydrating as water, right?” What do we know about carbonated water and its effects on our hydration status?

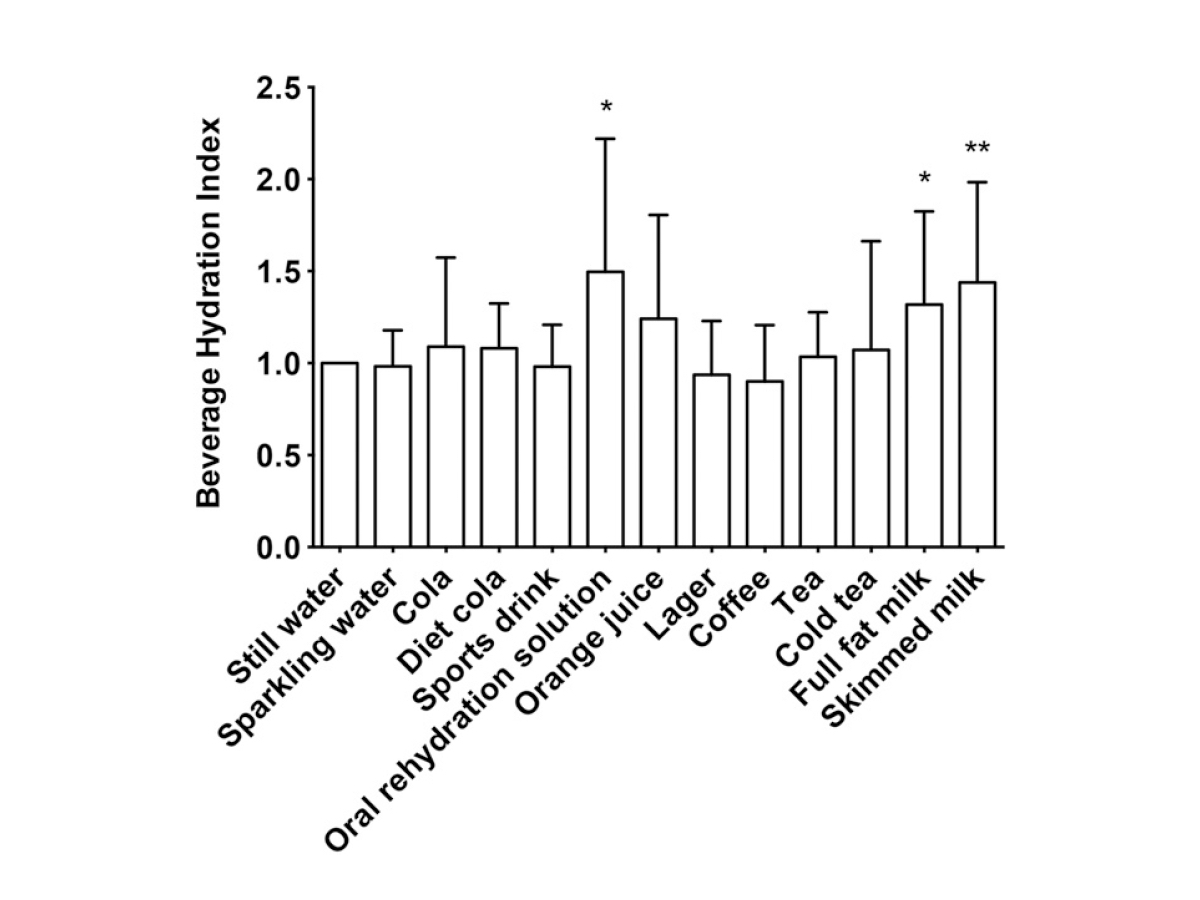

There is only one research paper in recent years about the hydrating quality of different beverages that include carbonated water. In this study, researchers compared the beverage hydration index (BHI) of different drinks. BHI uses how much urine is produced in a two-hour window following consumption of a beverage and from there, you can mathematically determine how much water was retained — thus producing a measurement of how hydrating the beverage is (1).

In the study, they compared tons of different drinks, including still water; carbonated water, beverages with macronutrient content like orange juice, cola, and full-fat milk; electrolyte beverages like sports drinks and oral rehydration solution; and beverages with diuretic agents like coffee and beer (1).

What they found was that beverages that contained carbohydrates, proteins, or fats left the stomach more slowly compared to still water, thus increasing their absorption. They also found that drinks high in electrolytes like the oral rehydration solution had the highest BHI — which is good, as it’s designed to be exceptionally hydrating (1). Most importantly to our question, carbonated water had a virtually identical BHI to still water, making it as hydrating.

One drawback of carbonated water is that it might pose a greater dental hygiene risk compared to regular water. This is because sparkling water contains carbon dioxide, which when combined with saliva becomes carbonic acid, making your mouth more acidic (2). What this means is that carbonated beverages like bubbly water can be erosive to your teeth, putting you at higher risk for cavities over time (3). While there isn’t a ton of research in this space, we know that carbonated water is still less erosive than soda or fruit juice (3) but should maybe be consumed in moderation.

The last thing to consider is that when you drink carbonated beverages you are swallowing that carbonation — those bubbles have to go somewhere! And in classic “better out than in,” that generally results in belching or flatulence. If you regularly deal with bloating or gas, then you might want to go light on the bubbly.

You can learn more about the basics of maintaining your hydration status while exercising.

Conclusion

Fiction! While the research is not abundant, from what we can tell, carbonated water and still water are equally hydrating. However, take care of your teeth, and go light on the carbonated water.

A graph showing the beverage hydration index of various drinks. Carbonated water performed almost identically to still water suggesting a comparable hydration index. Image: Maughan, R. J., Watson, P., Cordery, P. A. A., Walsh, N. P., Oliver, S. J., Dolci, A., Rodriguez-Sanchez, N., & Galloway, S. D. R. (2015). A randomized trial to assess the potential of different beverages to affect hydration status: Development of a beverage hydration index. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(3), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.114769 (1)

Fact or Fiction: “You need a caffeine cleanse in order to get performance benefits from caffeine on race day.”

Caffeine is probably the most popular ergogenic aid/performance-enhancing substance that is readily available and legal to use in and outside of competition. I’m going to cite myself with iRunFar’s in-depth article about caffeine as a performance enhancer and say, “The most likely reason that caffeine aids performance is that it decreases feelings of fatigue. Caffeine acts as an antagonist (direct competition) of the neurotransmitter adenosine by binding directly to the adenosine receptors that are found throughout our bodies, specifically the A1 and A2a receptors. This blunts the effects of adenosine, whose role includes promoting sleep and suppressing arousal (4).”

As caffeine boxes out adenosine, it keeps you more alert and reduces your perceived exertion and pain during exercise. All of which is pretty great! However, not everyone experiences performance improvements from caffeine. Roughly one-third of us don’t experience much improvement at all. While this used to be partially attributed to habitual caffeine ingestion and building up a tolerance to it, we now believe this has a lot more to do with genetics, age, and the timing, type, and dose of caffeine ingested (4).

A massive meta-analysis, released in March of 2022, wanted to get to the bottom of this very idea (4). What they found was that habitual caffeine consumption did not affect the ergogenic effect of caffeine on athletic performance across sport type (whether power, strength, or endurance efforts), gender, or training status (4).

They also highlighted that a caffeine withdrawal was unnecessary to see performance benefits from pre-training or pre-competition caffeine ingestion and that if anything, a caffeine withdrawal had more negative side effects for most athletes like headaches, fatigue, anxiety, and irritability (4). Finally, they further elucidated the idea that both high and low habitual caffeine users did not need to increase their pre-exercise caffeine dose in order to achieve a performance bump (4).

Conclusion

Fiction! Cleansing yourself of caffeine pre-competition is not currently supported by the literature. What this means is that you can spare yourself the caffeine withdrawal and continue to indulge in your caffeine habit and still experience a kick — even from a dose lower than your habitual amount — come race day (4).

Regular caffeine use won’t prevent you from using it to enhance your race-day performance. Photo: iRunFar/Meghan Hicks

Fact or Fiction: “Hot weather makes me more likely to cramp.”

The likelihood is you’ve been there, maybe it was mile 18 or maybe it was mile 80, but suddenly a muscle starts to seize. Perhaps it’s your calf — or if you’re me, it’s my left quad — that cramps and requires a trailside stretch so that you can keep going.

These cramps, technically referred to as exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMC), are defined by painful spasms and involuntary contractions of your skeletal muscles either during or immediately post-exercise. EAMC excludes cramps that can occur outside of this context and are the result of underlying medical conditions as opposed to exercise. You can learn a whole lot more about exercise-associated muscle cramping in our in-depth article.

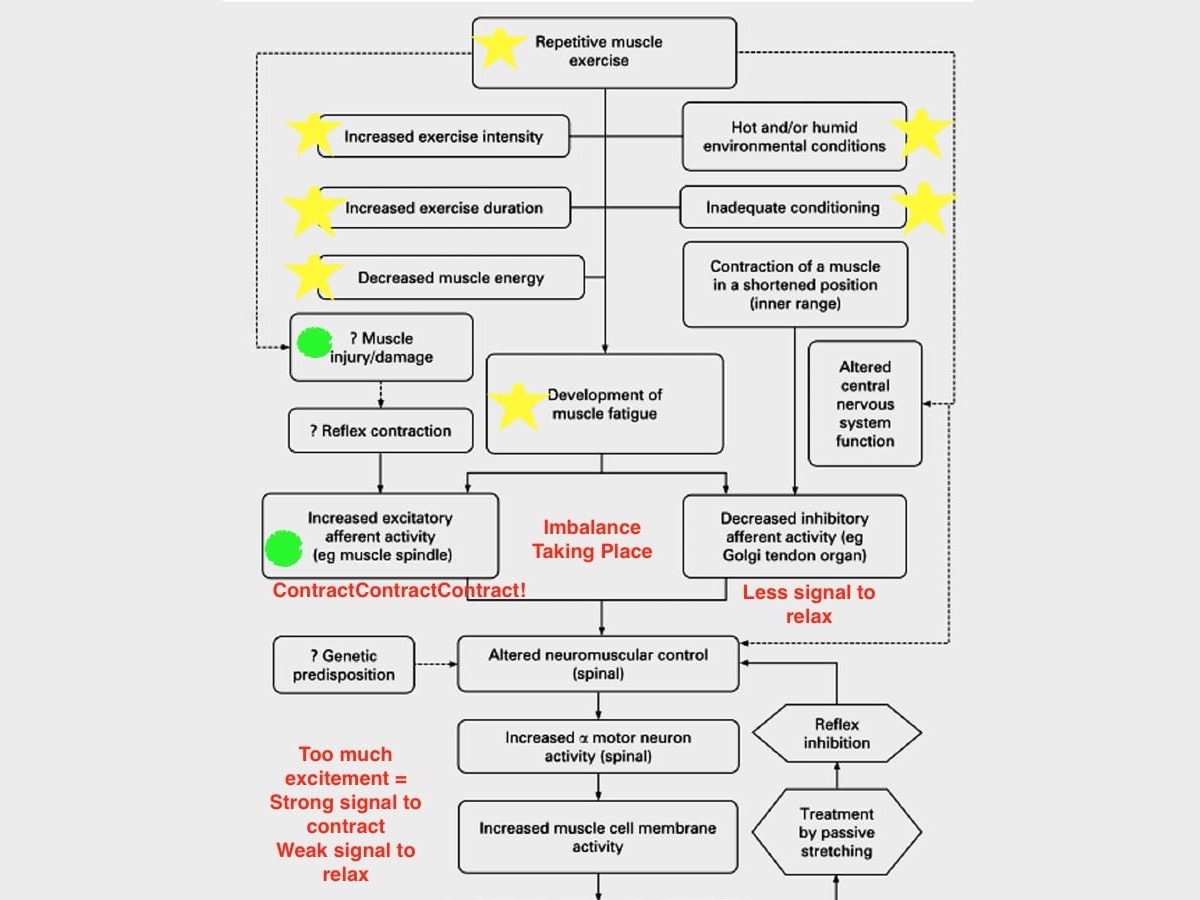

With their prevalence, there have been many theories over the past decades as to why we might experience EAMC, including the dehydration theory, the electrolyte depletion theory, the altered neuromuscular control theory, the salty sweating theory, and the environmental theory (5).

The last of these theories, regarding the environment, suggested that hot environments provoked EAMC. While this was quickly rejected — we can’t make people cramp from passive heating — EAMC is still five times more likely to occur in hot environments (5, 6). What gives?

A runner tops a dune during the 2021 Marathon des Sables. While heat doesn’t cause cramps while running, it can be a contributing factor to their development. Photo: Marathon des Sables/Erik Sampers

From years of research we know that while dehydration and electrolyte depletion can play a role in EAMC, they are not the linchpins. However, they play into the overarching enemy of the ultrarunner: muscle fatigue (altered neuromuscular control theory) is a trigger for EAMC. The idea behind the muscle fatigue theory is that a combination of factors can influence how muscles function. As muscle fatigue develops, the excitatory signal to contract the muscle becomes stronger than the muscle’s signal to relax. And as 50% of you have likely experienced before, your muscle suddenly doesn’t want to relax.

The question becomes, how does heat affect muscle fatigue? Heat, like dehydration, can influence neuromuscular control of your nervous system, and when combined (not on its own) with other factors contributing to muscle fatigue, can push us over the edge into a cramp-prone state. Essentially, heat by itself doesn’t create EAMC, but thermal stress combined with fluid and electrolyte loss, extended endurance exercise, and improper fueling is a recipe to put you on the side of the trail.

Conclusion

The truth is something in between fact and fiction! While heat on its own does not make you more prone to cramping, it can exacerbate muscle fatigue, which can lead to EAMC. Maybe this is another reason to prioritize a little heat acclimation ahead of your next warm-weather race.

Yellow stars represent the potential variables impacting muscle fatigue. Green circles indicate additional causes of neural imbalance telling the muscle to contract more. Image is from Schwellnus M. Cause of exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMC) — altered neuromuscular control, dehydration, or electrolyte depletion? Br J Sports Med 43: 401–408, 2009 (6) and has edits by the author.

Call for Comments

- Are you a bubbly water drinker? Have you anecdotally experienced it to be more or less hydrating than regular water for you?

- Do you find that you can normally consume caffeine and still have it give you a boost when you’re racing?

- Have you experienced exercise-associated muscle cramping? If so, do you have an idea of the circumstances that caused it?

References

- Maughan, R. J., Watson, P., Cordery, P. A. A., Walsh, N. P., Oliver, S. J., Dolci, A., Rodriguez-Sanchez, N., & Galloway, S. D. R. (2015). A randomized trial to assess the potential of different beverages to affect hydration status: Development of a beverage hydration index. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(3), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.114769

- Caron, C. (2021, September 14). Is carbonated water just as healthy as still water? The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/14/well/eat/seltzer-water-benefits.html

- Reddy A, Norris DF, Momeni SS, Waldo B, Ruby JD. The pH of beverages in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(4):255-263. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2015.10.019

- Carvalho, A., Marticorena, F. M., Grecco, B. H., Barreto, G., & Saunders, B. (2022). Can I have my coffee and drink it? A systematic review and meta-analysis to determine whether habitual caffeine consumption affects the ergogenic effect of caffeine. Sports Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01685-0

- Schallg, W., Levels, K., & Daanen, H. A. M. (2017). The influence of heat on the occurrence of exercise associated muscle cramps: a review.Sport En Geneeskunde.

- Schwellnus M. Cause of exercise associated muscle cramps (EAMC)– altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? Br J Sports Med 43: 401–408, 2009