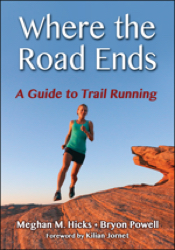

If you enjoy this article, then get your own copy of the book “Where the Road Ends!”

Welcome to this month’s edition of “Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running,” a how-to on managing severe weather and terrain written for newer trail runners as they prepare for longer runs into more remote areas.

“Where the Road Ends” is the name of both this column and the book Meghan Hicks and Bryon Powell of iRunFar published in 2016. The book Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running is a how-to guide for trail running. We worked with publisher Human Kinetics to develop a book so anyone can get started, stay safe, and feel inspired on the trail.

The book teaches you how to negotiate technical trails, read a map, build your own training plan, understand the basics of what to drink and eat when you run, and so much more. This column aims to do the same by publishing sections from the book, as well as encouraging conversation in the comments section of each article.

In this article, we bring you an excerpt from Chapter 10 to share ideas for dealing with extreme weather and terrain. We want you to be safe as you advance your trail running skills and head deeper into your favorite trail networks.

Running in the mountains in the spring and early summer means using care with extreme terrain and weather. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Extreme Weather

We’ve discussed before how to deal with rain, snow, heat, cold, and sun in enough detail to make your trail runs through them as enjoyable and comfortable as possible. But we want to mention two other kinds of weather trail runners should be prepared for before trail running through the backcountry.

Lightning

Though it’s largely preventable, every year a few outdoor recreationists are struck by lightning. For the most part, lightning becomes a risk in exposed areas, like a high, open meadow or a ridgeline or mountaintop that doesn’t have the protection of trees. Lightning occurs mostly during summer and fall thunderstorms, which tend to build up after midday and sometimes continue into the night. To avoid lightning, very simply leave those exposed areas when thunderstorms are building or occurring.

If you are in the mountains and thunderstorms are forecasted, plan to be back down into the relative protection below the treeline by noon, or earlier if you see weather forming. In other regions, don’t cross meadows or high bald hills during a thunderstorm. The same rule holds true for more urban road running or trail running: If a thunderstorm is in progress, don’t run through a wide, open area.

If you find yourself in an exposed location and a thunderstorm approaches, use your trail running skills to sprint back to cover. If this isn’t possible and you have to wait out the storm in a precarious place, get into what’s called the “lightning position.”

Separate yourself from any metal you have with you and your companions by about 50 feet (15 meters). Squat with your feet together, keeping only your feet on the ground. Wrap your arms around your legs. Don’t allow your butt or hands to touch the ground because this additional contact point can create a line through which electrical current can flow through your body should lightning strike. Stay in this position until the storm passes.

To learn more, read our detailed lightning safety guide.

High-Water Crossings and Flash Floods

Water crossings are an unavoidable and adventurous aspect of trail running. But, sometimes a stream can be quite big! Take note that in many places, stream depth varies over the course of a day as well as when there’s bad versus good weather. During snowmelt season, for example, streams that are small in the morning can rise a lot in the afternoon and early evening. And streams can swell by huge amounts after a short but big storm or a day of steady rain. Don’t cross a stream if it feels dangerous to do so.

Flash floods occur mostly in desert ecosystems after a significant amount of rain falls during a short time. Desert ecosystems generally lack absorbent soil, and solid rock allows rain to run off downhill, pooling into gullies and canyons. These gullies and canyons can become flooded within a matter of minutes in or after heavy rainfall. Avoiding flash floods is as easy as avoiding lightning. Don’t go into a low place before, during, or even after a storm.

A group of runners cross fast-moving water during the Squamish 50 Mile/50k race. Photo courtesy of Gary Robbins.

Extreme Terrain

Surmounting terrain challenges is part of trail running. Some trail runners find terrain challenges so enjoyable that they seek out routes that include a great deal of elevation change, technicality, or other challenges. In this section, you’ll learn how to take on a couple of terrain challenges that might seem daunting at first (or 400th) pass.

Exposure

Some humans have it in their nature to be uncomfortable with exposure — an open and airy location — and heights, whereas others are unbothered. No matter your proclivity, you should use care when a trail travels through an area with steep drop-offs. Cliffs can warrant walking, because moving across one would be a very bad time to catch a toe!

If you have some wiggle room in the width of the trail tread, use that space to stay away from the cliff. For travel through extensive exposure, the use of your hands or trekking poles can add stability. Look in the direction of where you’re headed, not down the exposure.

If you are the kind of person who goes weak-kneed at the sight of steeps, that’s totally all right. It’s always okay to head back down.

Snowfields

Snowfields can be short or long bits of snow that are left over in high alpine locations from the previous winter. They are common during the early summer season on the north and east slopes of mountains or high passes. Snowfields can be fun, but sometimes they are dangerous.

When you encounter a snowfield, observe the hardness and steepness of the snow. Generally, if a snowfield is flat or nearly so, it will be safe to cross, because even if it’s slippery and you fall, you won’t slide anywhere. If the snow is frozen solid and doesn’t give in any direction under your feet, and is steep, crossing it is dangerous. A fall could turn into a slide that ends in serious injury.

If you encounter a snowfield like this, scan the terrain for a way to get around the snowfield on bare ground or flat terrain. Get past the snowfield this way if it’s safe and doesn’t damage the environment to do so. With proper light mountaineering equipment including crampons and an ice axe, as well as the skills to use this equipment properly, crossing a frozen, steep snowfield is possible.

Suppose that you encounter a snowfield that is steep but soft, and you are able to kick flat steps into it or follow the steps of people who have come before you. Before you decide to cross, consider a couple of things. Be aware that some snow, even though it’s soft, can still be slippery.

Also, consider what might happen if you are going to a mountain peak and have to return the same way. Will the snow freeze and harden again before you return? You will have to use your best judgment to decide whether to cross the snow.

The avalanche danger that skiers experience in the winter can be present for trail runners on spring runs over snow. If an avalanche is possible, don’t cross or travel underneath steep snow.

Finally, exercise caution on snow bridges, the snow that covers creeks or streams, which is a common feature of many environments during winter and spring. You will be tempted to use such snow to cross creeks in lieu of submerging your feet in cold water. But these features are extremely dangerous because they can collapse, thereby flushing you into the water and underneath the snow downstream.

Disappearing Trail

A good singletrack trail may occasionally disappear, almost as if by black magic. One minute you are running along an easily discernable trail, and in another minute — poof!

If the tread of the trail you’re running on disappears, look for other signs of the direction you’re supposed to travel. Stacks of rocks made by humans called cairns, paint or other markings on exposed rock surfaces, hash marks in the bark of trees, and small trail markers hanging from trees are all directional indicators. Keep your eyes peeled for details, because there is almost always a human-made hint of where you need to go.

In this photo, a trail disappears into snow as it heads toward a mountain pass. Photo: iRunFar/Bryon Powell

Excerpted from Where the Road Ends: A Guide to Trail Running, by Meghan Hicks and Bryon Powell. Human Kinetics © 2016.

Call for Comments

- Can you remember the first time you encountered severe weather or terrain while trail running?

- What mistakes have you previously made with weather and terrain that you would have liked to know about ahead of time?

- What questions do you have about the specific kinds of extreme weather and terrain around where you live and run?