Thanks to several high profile athletes sharing their mental health journeys in a public way, the discussion around mental health in sports is poised for prime time. First came “The Weight of Gold,” a documentary about the mental health challenges that Olympic athletes often face, and then followed the brave act of American gymnast Simone Biles at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, when she removed herself from competition citing too much strain on her mental health. What is slowly emerging from these moments is an understanding that an athlete’s physical health does not equal their mental health.

All of this said, there’s a dearth of research on mental health in athlete populations, so little is yet known about this subject beyond individual athlete stories. Existing research on ultra-endurance athletes focuses on the physical health and physiological determinants and demands on these athletes, overlooking mental health almost entirely. What we do know is that stigma, denial, and the unfortunate separation of physical and mental health have likely left many athletes under-diagnosed and under-treated for mental health disorders (3).

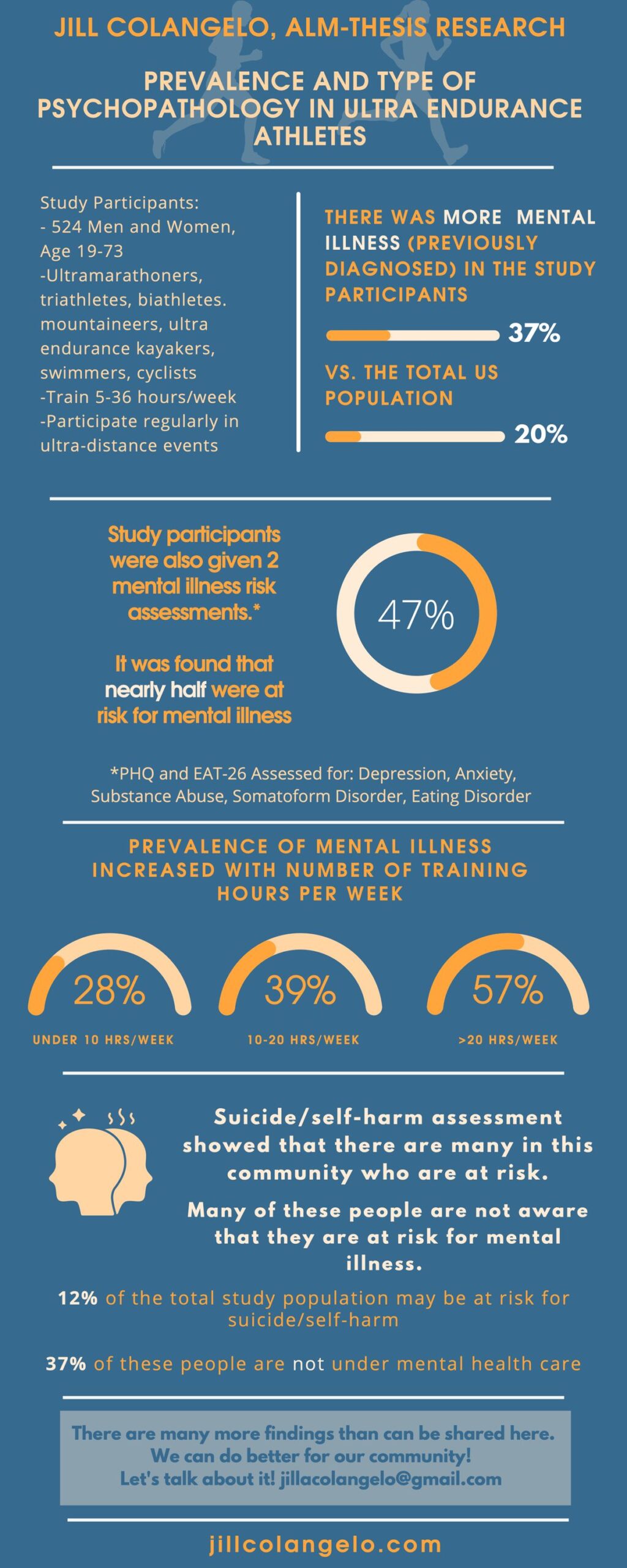

Enter Jill Colangelo and her Masters of Liberal Arts-Psychology thesis from Harvard Extension School titled “Prevalence and Type of Psychopathology in Ultra Endurance Athletes,” which was published in May of this year. In summary, the paper found mental health issues to be more prevalent in the population of ultra-endurance athletes who participated in the study than in the general population. Of course, we’ll explore the findings of this work — as well as its limitations and where future research could focus — in more detail throughout this article. But this research continues to spur the important conversation around the mental health and well being of ultra-endurance athletes — that means you and your friends!

The 2019 The North Face 50 Mile Championships starting line. Photo: iRunFar

Physical Health Does Not Equal Mental Health

We know the mental health of endurance athletes is often overlooked in research. Famously, in the ULTRA study conducted by physician and runner Dr. Marty Hoffman and his colleagues, mental health was completely omitted from their outcome measures, and instead, they focused only on physical injury, illnesses, missed days of work or school, and the onset of chronic diseases such as heart disease or diabetes (4). Similarly, other studies have looked at psychological demands experienced by ultra-endurance athletes, but the focus is on mindset for performance and not overall mental health.

That said, there is an established link in the scientific literature between a moderate amount of exercise (even 20 to 40 minutes three times per week) and improved mental health outcomes. This suggests that moderate physical activity could and maybe even should be used as a treatment for things like mild to moderate depression as a means to improve symptoms and quality of life (6).

A Dose-Response: How Training Volume Affects Mental Health

If a little exercise is good, then is more a whole lot better? Medically, a dose-response refers to the curve in which a drug has little response at super low doses, and no added benefit at super high doses, with the most effective dose being somewhere in the middle of that curve. The scientific literature tell us that the relationship between exercise and mental health may have its own curve. This means, in contrast to an assumption that “ever-increasing volumes of exercise would offer ever-increasing health benefits, there may be a U-shaped relationship between benefits of participation and training volume” (1).

For example, a 10-year-long study at the University of Wisconsin-Madison assessed moods and training loads of college swimmers, and found that the highest level of mood disturbances always corresponded with the highest volume training block – every January (7). Additionally, these increased training volumes were associated with increased fatigue, decreased vigor, and increased depression and anger (7). But just as consistently, mood improved (back to baseline or above) as training volume decreased.

Prior to Colangelo’s research, there had been no study on the ultrarunning community examining this dose-response effect of exercise on mental health.

Previous Work on Mental Health Disorders in the Ultra-Endurance Community

So if increased training volume possibly increases mental health disorders in other athletic populations, how vulnerable is our community? In 2018 and 2019, following a number of stories highlighting the mental health challenges of ultrarunners Nikki Kimball and Rob Krar, it became apparent that there might be increased risk of depression and suicide in the ultra-endurance community (2). This led psychiatrist and ultrarunner Dr. John Onate to suggest that this population is often overlooked for diagnosis of mood disturbances because they “appear healthy.” Of the research done with ultra endurance athletes, the mental disorders that are most prevalent and therefore most focused on are depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and exercise addiction.

Jill Colangelo’s Study on Mental Health in Ultra-Endurance Sports

With her thesis, Jill Colangelo set out to explore mental health in ultra-endurance sports. Calls for ultra-endurance athletes to participate in the study were made on a variety of platforms, including here on iRunFar. In the end, 523 runners, skiers, cyclists, biathletes, adventure racers, triathletes, and more participated.

The study participants were made up of 213 women (40.83%) and 310 men (59.35%), and were further divided into three categories, those training under 10 hours a week (50 women and 88 men), those training 10 to 20 hours a week (145 women and 210 men), and those training 20-plus hours a week (18 women and 12 men). The participants then completed several surveys, and were also asked if they had been diagnosed previously with a mental health disorder. The first survey they completed was a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) designed to screen for five common mental health disorders: depression, anxiety, somatoform disorders, alcohol abuse, and eating disorders. The second survey they completed was an Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) designed to measure and assess risk of eating disorders including anorexia, bulimia, and patterns of disordered eating.

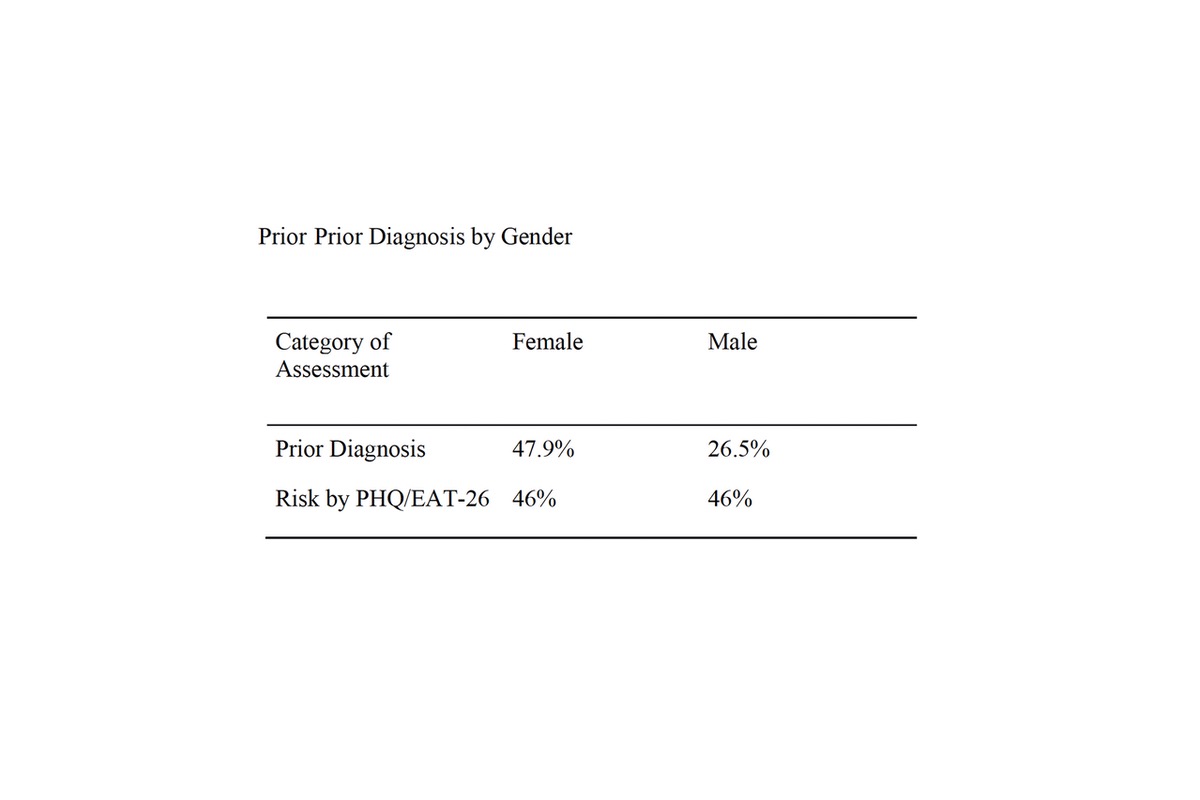

Strikingly, both men and women reported a much higher percentage of a previous mental health diagnosis than in the general U.S. population. That is, the incidence of a mental health diagnosis in the general U.S. population is around 20%, whereas 47.9% of the female study participants and 26.5% of the male study participants reported a previous diagnosis.

Interestingly, more women reported a previous mental health diagnosis than men in the study, despite the risk for mental health disorders (as indicated by the results of the PHQ and EAT-26 surveys they all took) being equal for both sexes, 46% for both males and females. This implies that there are likely male athletes in our community who are not receiving care for a possible mental health disorder. This tracks with global trends, in which males are three to four times more likely to die by suicide than females, despite females being far more likely to be diagnosed with and treated for depression (8).

Also of note, as training volume increased, the likelihood of having a previous diagnosis also increased, suggesting there is a negative relationship between training volume and mental health. It’s really important to note now that this relationship is often referred to as a correlation in research, where we know the two variables of training volume and mental health disorders are connected, but we don’t know if there’s causation between them.

The participants who had previously been diagnosed with a mental health disorders reported 105 for depression, 91 for anxiety, 42 with an eating disorder, 19 with post-traumatic stress disorder, six with obsessive-compulsive disorder, eight with bipolar disorder, five with panic disorder, and four with dysthymia (persistent depressive disorder). Additionally, 30 participants reported that they were currently in recovery for alcohol addiction. Once again, the incidence for having a previous diagnosis trended upward with training volume and at much higher rates than what is seen in the general U.S. population.

This table shows the percent of females and males with prior diagnoses of mental health disorders and their suggested risk for a mental health disorders based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) and Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) surveys conducted during the study. All images courtesy of Jill Colangelo unless otherwise noted.

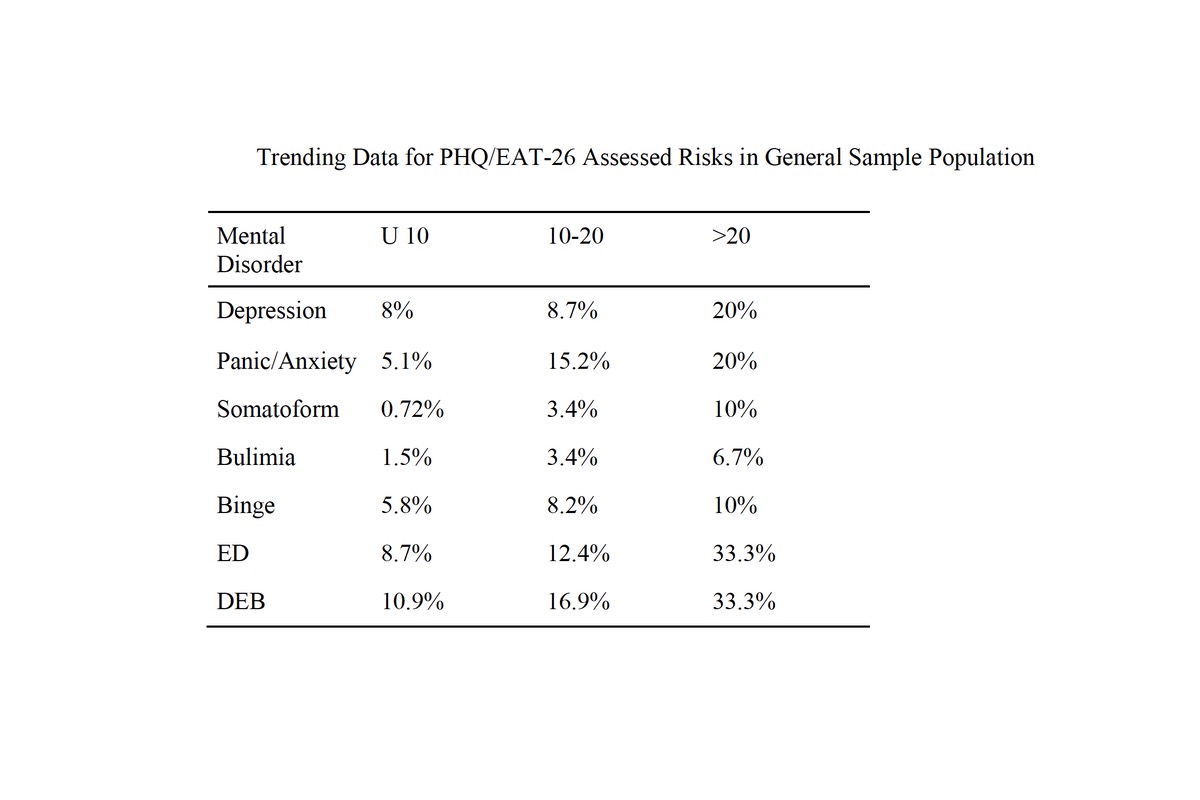

We include two more tables of note. The next table looks at the assessed risk of being diagnosed with common mental health disorders compared to average training volume. Across the board, the risk of a mental health diagnosis went up as training volume increased.

This table shows the assessed risk in the study participants for common mental health disorders compared to training volumes. U10 is under 10 hours of exercise per week, 10-20 is 10 to 20 of exercise per week, >20 is 20-plus hours per week, ED is an eating disorder, and DEB is disordered eating behaviors.

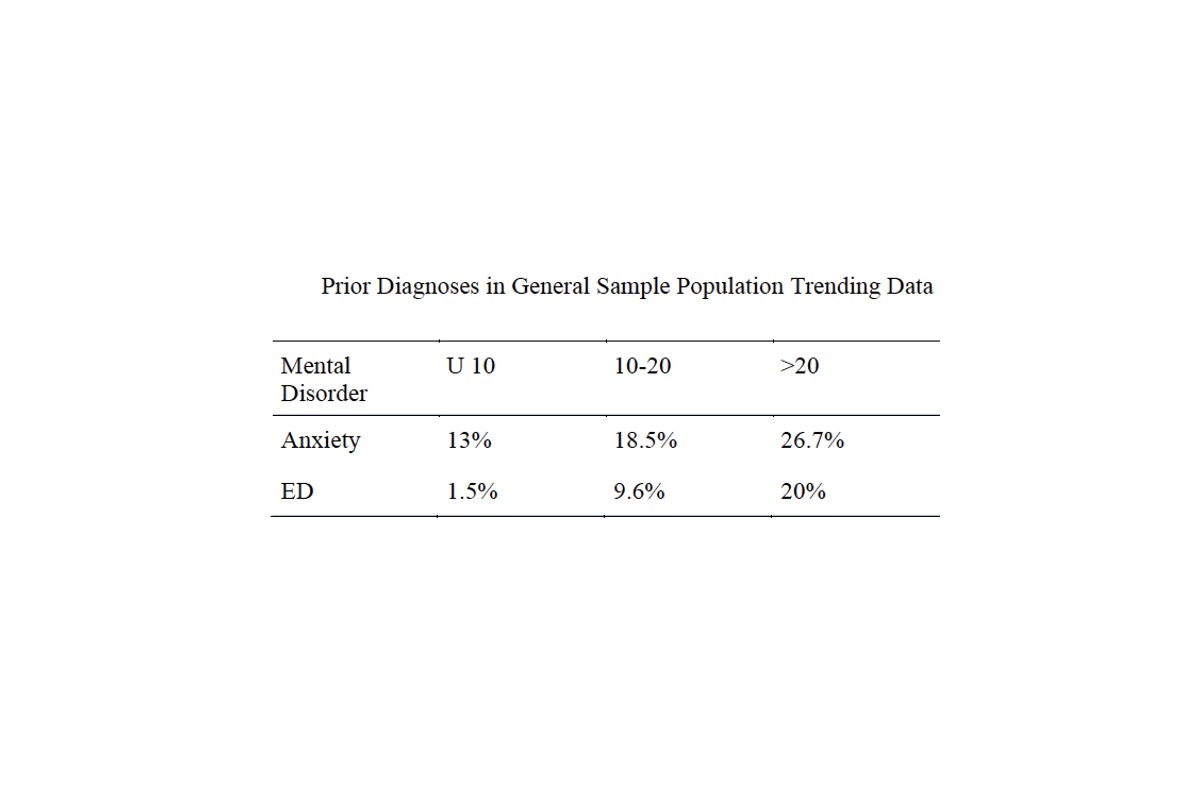

The final table looks at the rates of previous diagnosis, specifically of anxiety or an eating disorder compared to training volume. Again, the volume of previous diagnosis for both went up as training volume increased.

This table highlights the prevalence of a prior diagnosis of anxiety or an eating disorder (ED) compared to the participants’ training volume, with likelihood of a previous diagnosis increasing with training volume. U10 is under 10 hours of exercise per week, 10-20 is 10 to 20 of exercise per week, and >20 is 20-plus hours per week.

Key Thoughts About Mental Health in Ultra-Endurance Sports

Through this work, we’ve learned that mental health disorders and ultra-endurance sports are connected in some way. The truth is, we still have a lot to learn on this topic and much more research needs to be done.

Colangelo’s paper highlights both the limitations of the work as well as next potential research steps:

- This research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have had additional effect on participants’ mental health.

- Survey-based research comes with multiple possible biases, everything from the kind of person who would choose to participate in this study to the fact that some people might be unable to complete their participation in the study if triggered by its sensitive nature.

- Perhaps most important, we don’t know how mental health disorders and ultra-endurance sports are linked.

That final point is a real chicken-or-the-egg question. Are people with mental health disorders more likely to be drawn to ultra-endurance sports, or does participating in these sports make you more vulnerable for developing a mental health disorder? Which comes first?

As you can see, we still have some big, outstanding questions that may shape the way we train and view our own sport. Much more research is needed to fully understand mental health among ultra-endurance athletes. But for now, what we do know is that there is a significant amount of mental health disorders in our community.

More than anything, we want this article to promote an open dialogue about mental health amongst those with whom we share the trails and roads. As summed up by Colangelo, “Despite our cultural affinity toward extreme feats of athleticism, high volume training may be less indicative of personal success and more indicative of the need for mental health support.”

Call for Comments

- Do you think there is still a stigma surrounding seeking help for mental health?

- Have you struggled with mental health when increasing your training load?

Finding from Jill Colangelo’s graduate thesis research study.

References

- Colangelo, Jill Ann. 2021. Prevalence and Type of Psychopathology in Ultra Endurance Athletes. Masters of Liberal Arts-Psychology thesis, Harvard University Division of Continuing Education.

- Onate, J. (2019). Depression in ultra-endurance athletes, a review and recommendations. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 27(1), 31-34. doi:10.1097/jsa.0000000000000233

- Schwenk, T. (2000). The stigmatisation and denial of mental illness in athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(1), 4-5. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.1.4

- Hoffman, M., & Krishnan, E. (2014). Health and exercise-related medical issues among 1,212 ultramarathon runners: Baseline findings from the Ultrarunners Longitudinal TRAcking (ULTRA) Study. Plos ONE, 9(1), e83867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083867

- McCormick, A., Meijen, C., & Marcora, S. (2016). Psychological demands experienced by recreational endurance athletes. International Journal of Sport And Exercise Psychology, 16(4), 415-430. doi: 10.1080/1612197x.2016.1256341

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Hallgren, M., Firth, J., Veronese, N., & Solmi, M. et al. (2018). EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: a meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). European Psychiatry, 54, 124-144. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004

- Morgan, W., Brown, D., Raglin, J., O’Connor, P., & Ellickson, K. (1987). Psychological monitoring of overtraining and staleness. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 21(3), 107-114. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.21.3.107 8. BBC. (n.d.).

- Why more men than women die by suicide. BBC Future. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190313-why-more-men-kill-themselves-than-women.