Should you worry about being attacked by a mountain lion on your next trail run? No. Definitely not. The odds of winning the Western States 100 cougar trophy are better than being attacked by one. (Mountain lions have more names than whiskers. Some of the most commonly used ones are cougar, puma, and panther.) There have been about 150 documented mountain-lion attacks and about 20 fatalities in the United States and Canada since 1890. Dogs kill more people annually. And, as far as I can tell, only six of the mountain-lion attacks involved runners. Two of these runners were killed.

Now, if you’re a worrier like me and your email and social media have been filled with news of that Colorado trail runner’s attack in February, then your brain has likely translated those statistics to: Runners have been attacked and killed by mountain lions since 1890! Moveover, that’s just documented attacks. How many more haven’t been recorded?

So let’s break down your risk based on where you’re running and racing. And then we can talk about how to mitigate that risk and what to do in the very unlikely event a mountain lion decides you look tastier than anything else around. The goal of this article is to address your parents’ worries that you’ll be attacked by a mountain lion while you’re out trail running–and maybe your concerns too.

I won’t address the mountain lion’s important relationship to the ecosystems they live in, their reduced habitat due to human encroachment, their innate value, or their awesomeness. To read more about that, please check out the resources on the Mountain Lion Foundation’s website.

Oh, and one more thing, this article is focused on North American mountain-lion populations. Mountain lions live in South America, too, where they are usually called puma. They are the same species, but their behaviors around humans are different.

Where Mountain Lions Live

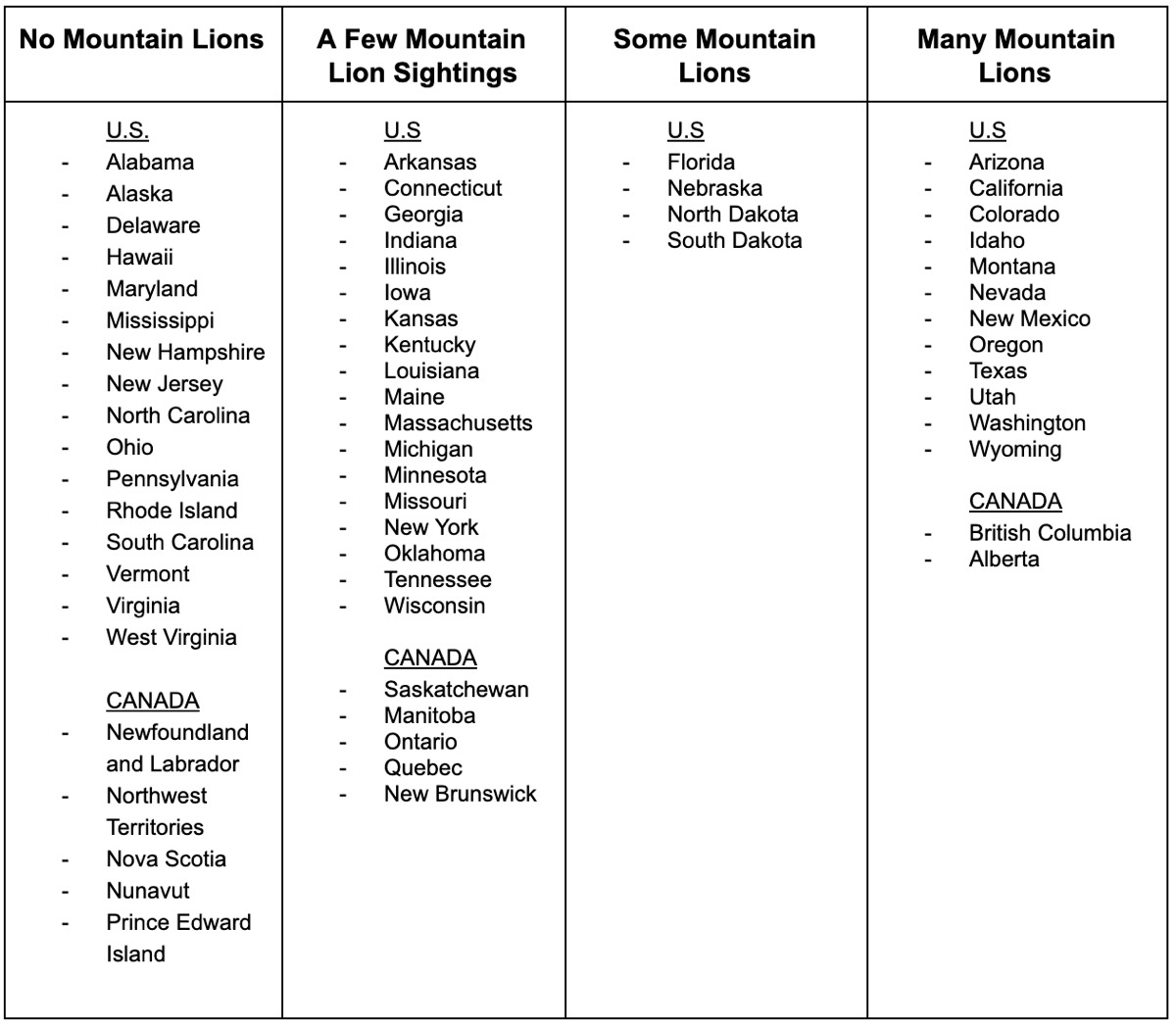

You’re probably more likely to get into the Hardrock 100–and win it–than to see a mountain lion east of the Mississippi River. There are no mountain lions in Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Nunavut, and Prince Edward Island.

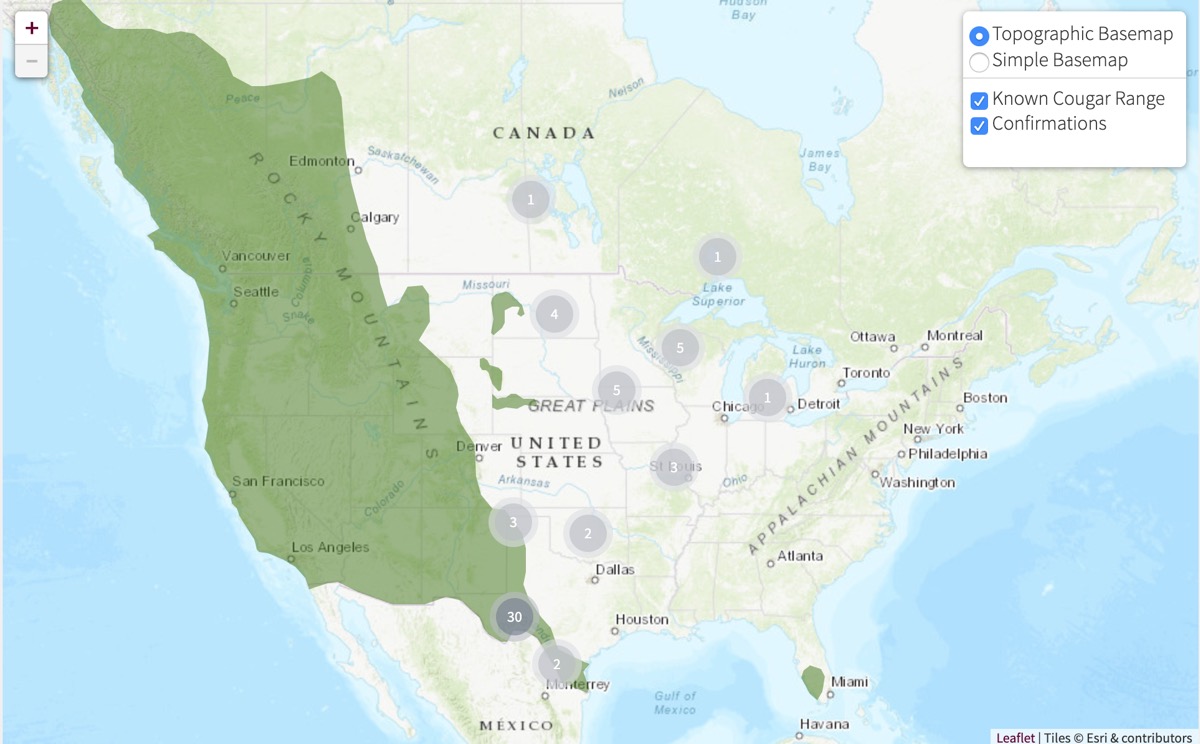

In fact, east of the Rocky Mountains, the only breeding mountain-lion populations are in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Florida. That’s not to say there aren’t other mountain lions wandering around east of the Rockies. They’re just few and far between. Take a look at the map below to see how many mountain-lion sightings there were in 2017 outside their established range.

A map showing mountain-lion range in green and mountain-lion sightings outside of their known range in 2017 in grey circles. Image is a screenshot from the Cougar Network’s interactive map.

As a bonus, check out the interactive version of the above map created by the Cougar Network, a non-profit that tracks expanding cougar populations, to see the exact locations of these sightings or to explore data from other years.

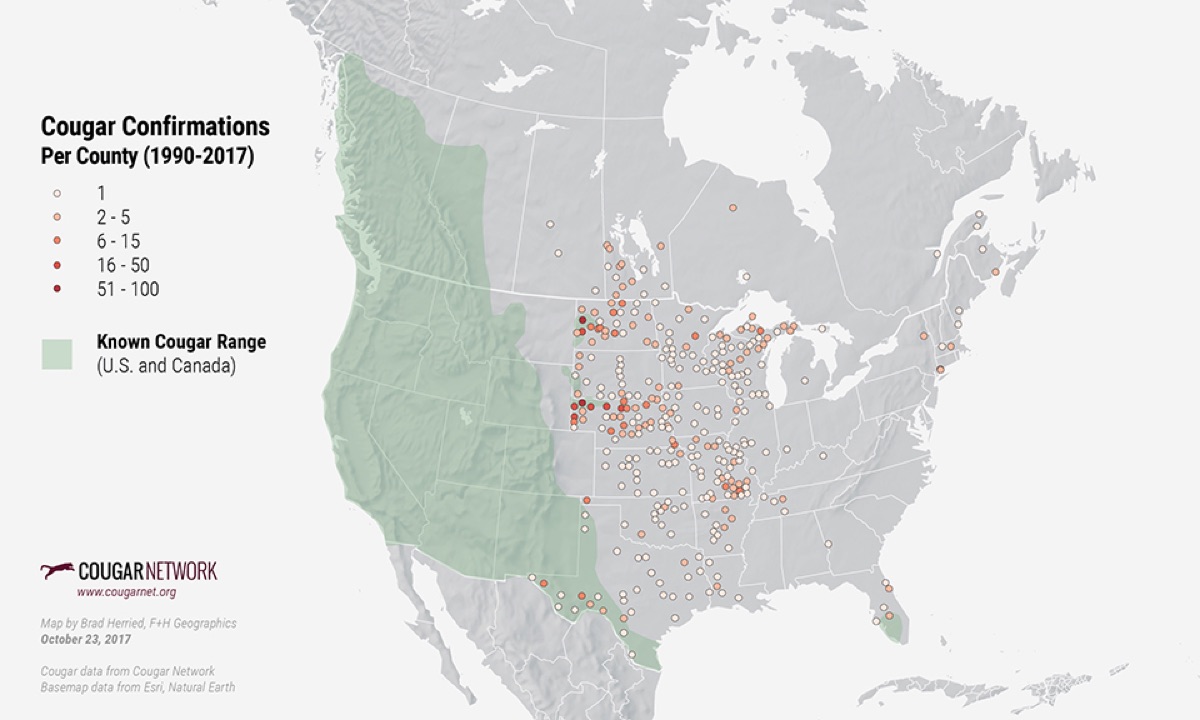

Mountain-lion populations are rebounding after being extirpated in the Midwest and eastern United States in the last century. They’re returning to old habitats and, also, populating new areas. This recovery, combined with suburban sprawl, increases the likelihood of sightings and encounters.

A map showing confirmed mountain-lion sightings from 1990 to 2017 outside of their known range. Image: Cougar Network

A chart showing where you should and should not see mountain lions in North America. Image: Liza Howard

What to Do If You Come Face-To-Face with a Mountain Lion

That’s all well and good, you’re thinking, but what should I do in the unlikely event I do come face-to-face with a mountain lion? The answer is simple–at least in theory–don’t act like prey. That’s your goal. Ask yourself, What would a mouse do in a face off with a house cat? Then do the opposite.

A mouse is small. Don’t be small.

I know, I know, trail runners are generally fairly small people.

Instead, make yourself look as big as possible. And if you’re running with a buddy, get close together and seem like an even bigger creature.

A mouse is quiet. Don’t be quiet.

Yell at the mountain lion. Holler whatever comes to mind. Yelling “mountain lion!” might attract some help as well as scaring the lion off. But “I am not a mouse!” could work as well as anything if you say it loudly and sternly.

A mouse squeaks in fear. Don’t squeak.

This sounds like easy advice, but I think I’d likely scream in a mouse-like way if I ever rounded a corner on the trail and came face-to-face with a mountain lion.

A mouse tries to run to safety. Don’t try to run to safety.

I don’t care how well your training is going, you won’t outrun a mountain lion. Also, anybody who owns a house cat knows how cats love to chase things that are moving away from them. Basically, if you run, it’s game on!

Dr. Paul Beier, who verified and detailed all the fatal and non-fatal mountain lion attacks in the U.S. and Canada between 1890 and 1990, found only one person who had actually escaped by “panicked flight.” “In that case, a 16-year-old boy fled after encountering a cougar at 25 feet. The cougar was gaining ground rapidly when the boy’s boot fell off and the cougar attacked and ate the boot. This story was supported by the presence of boot fragments in the stomach of the cougar when it was shot an hour later.”

So, no running! (Unless you’re running in loose, tasty boots.)

A mouse is defenseless. Don’t be defenseless.

Pick up a big stick and wave it around. Throw rocks at the cat. Mountain lions aren’t looking for a good fight.

Mice freeze. Don’t freeze. And don’t play dead.

An attack in 1990 in Glacier National Park, Montana, chronicled by Dr. Beier, provides and arresting illustration of the foolishness of playing dead. “A nine-year-old boy said that he had been advised to play dead if he ever encountered a wild animal. When a cougar pounced on him as he was walking out of a lake, he followed this advice. However, the cougar continued to bite him and drag him away until his father kicked gravel at the cougar. The cougar then rushed at his seven-year-old sister; she did not play dead but screamed, causing the cougar to turn and run.”

A house cat playing with a very unfortunate mouse. Photo: Jamain (CC BY-SA 3.0)

In fact, don’t turn your back on the mountain lion either. According to the Mountain Lion Foundation, “The best way to ensure that both you and the lion may leave safely is for you to back away slowly while continuing to look as big and intimidating as possible, leaving the lion avenues of escape.”

“You have to assess the situation to know when to start backing away,” says Korinna Domingo, a conservation specialist with the foundation. “You need to establish that you’re not prey before you start backing away, especially if the mountain lion is exhibiting stalking behavior. Basically, the steps are: I see you. I’m not prey. Now I’m backing away.”

What to Do If You’re Attacked by a Mountain Lion

If the mountain lion decides you’re easy prey and attacks, fight back.

I was surprised at all the accounts of people successfully fighting off mountain lions with sticks, rocks, random outdoor gear, and their hands. Tom Chester, Linda Lewis, and Helen McGinnis list the details of most of the attacks since 1890 on their websites. (I’d like to apologize to my husband for reading most of these out loud before bed last night.)

During one attack north of Las Vegas, Nevada in 1991, a female research biologist was saved by her co-workers beating the lion with their cameras.

Travis Kauffman, the Colorado trail runner who was attacked on February 4th of this year, used sticks, rocks, and his hands and feet to save himself from the mountain lion. Travis was on a 12- to 15-mile run that started in Lory State Park outside Fort Collins, Colorado. He ran through Lory into Horsetooth Mountain Park to do some hill training. Shortly after he made it to the top of Towers Road, he heard pine needles rustle behind him. He turned his head and saw a mountain lion about 10 feet away. In an interview with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Travis said his “heart sank into his stomach.” (I bet it did!)

Then, Travis did everything right. He did not act like a mouse. “I threw my arms up and started yelling.” The cat kept approaching anyway. It lunged and latched onto his wrist and clawed at his face. Travis continued to do all the right things. He picked up sticks with his other hands and tried to stab the mountain lion. He aimed for the throat. Unfortunately, the sticks weren’t strong and broke. So Travis grabbed a rock and tried to bash the mountain lion’s head. The cat still had Travis’s left wrist in its mouth, which made it difficult for Travis to hit the cat’s head with much force. Travis eventually got his right leg close to his left wrist and was ultimately able to step on the cat’s neck and suffocate it.

Travis flew down the trail and away from the cat. He ran into another trail runner about two miles down the trail. That runner turned and ran back down the trail with Travis. The two met up with another pair of trail runners, who, along with the first runner, helped get Travis to the hospital and collected his car from the parking lot.

Travis did everything right. He was attacked and he fought back. I asked Lynn Cullins, Executive Director of the Mountain Lion Foundation, about criticism Travis had received because the mountain that attacked him was probably three to four months old and weighted 35 to 40 pounds. She did not equivocate: “If attacked, fight back. People who fight back, live. It’s not appropriate for us to second guess somebody’s behavior in a mountain-lion attack.”

How to Decrease Your Risk of Being Attacked

If you run where mountain lions live, you can decrease the risk of meeting up with one by taking these actions:

- Run with someone – You’re less likely to be attacked, and you’ll have help if you are. Travis Kauffman says he’ll be running with a buddy from here out.

- Make noise, so you don’t surprise the mountain lion – Mountain lions, like bears, hate surprises. Talk to your running buddy while you run. Lynn Cullins suggests clapping as you round blind corners. (Or just keep talking loudly.)

- Be alert and make noise before you squat down to go to the bathroom – You look less like a human and more like prey when you’re squatting. The position also exposes your neck and the back of your head. According to the Mountain Lion Foundation, “[T]his is where a lion will target an attack.”

- Don’t run with unleashed dogs – A frightened or aggressive dog might lead to an encounter rather than prevent one. A mountain lion might chase your dog and your dog might lead the mountain lion back to you.

- Don’t run with earbuds – Travis Kauffman attributes his success at fighting off the mountain lion to not wearing earbuds. “And one of the things I was really glad I did was turn my head [when I heard a noise behind me] and I couldn’t have done that if I had earbuds in.” You need to be aware of the noises in the environment around you when you’re trail running.

- Wear bright, contrasting pieces of clothing that break up your silhouette – According to Lynn Cullins, the less your clothes make your outline look like a deer, the better.

- Carry bear spray – Bear spray works on mountain lions too. But its usefulness depends on how quickly you can access and deploy it. The spray needs to be in front of your body in a quick-access holster or up front on your hydration pack. If you can’t pull it out quickly, it’s useless. If you decide to carry bear spray, practice deploying and spraying an inert training spray canister first. They’re inexpensive and the experience is invaluable.

- Be especially vigilant at dawn and dusk – Mountain lions are more active during conditions of low light.

- Don’t check out dead animals in the brush – (Duh!) This is how mountain lions store their food and they will not take kindly to you fiddling with it.

Three Things to Remember About Trail Running with Mountain Lions

- Your chances of encountering a mountain lion are probably less than getting into Hardrock your first try.

- If you come face-to-face with a mountain lion, don’t act like a mouse.

- If a mountain lion attacks, fight back!

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Have you ever seen a mountain lion while trail running or hiking?

- Have you ever had a close encounter with a mountain lion while trail running or hiking? Can you explain what happened?

- If you live where mountain lions do, what precautions if any do you to take to mitigate the risk of an encounter?