Jordan Marie Daniel is a fourth-generation indigenous runner and tenacious human-rights advocate. She’s perhaps most prominently known for firing-up global awareness for the missing and murdered indigenous women humanitarian crisis with a red handprint painted across her face, symbolizing violence, as she raced the 2019 Boston Marathon. And she’s a pioneer of intersectional activism—identifying and braiding together groups of various backgrounds for a mutual cause—as well as using her athletic platform to raise awareness and prompt vital dialogue about important issues.

Daniel, 33, currently lives on the Tongva Lands of Los Angeles, California, where she ventures to mountain trails each weekend. While trail running is a relatively new facet of running for her, running is in her blood. She’s run since age 10, when her grandfather ushered her inaugural road run.

Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel. All photos courtesy of Jordan Marie Daniel unless otherwise noted.

Daniel was born in South Dakota, where she was raised with the community and ceremonies of her tiospaye, a Lakota word for extended family, in the towns of Lower Brule and Chamberlain. The towns sit 32 miles apart, each resting against the banks of the Missouri River, near the Big Bend, in the state’s southeast corner. Daniel’s full name is Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel, and she’s a citizen of the Kul Wicasa Oyate, also known as the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, who are the landkeepers of the region’s rolling grasslands, full of buffalo, sharp-tailed grouse, and coyotes.

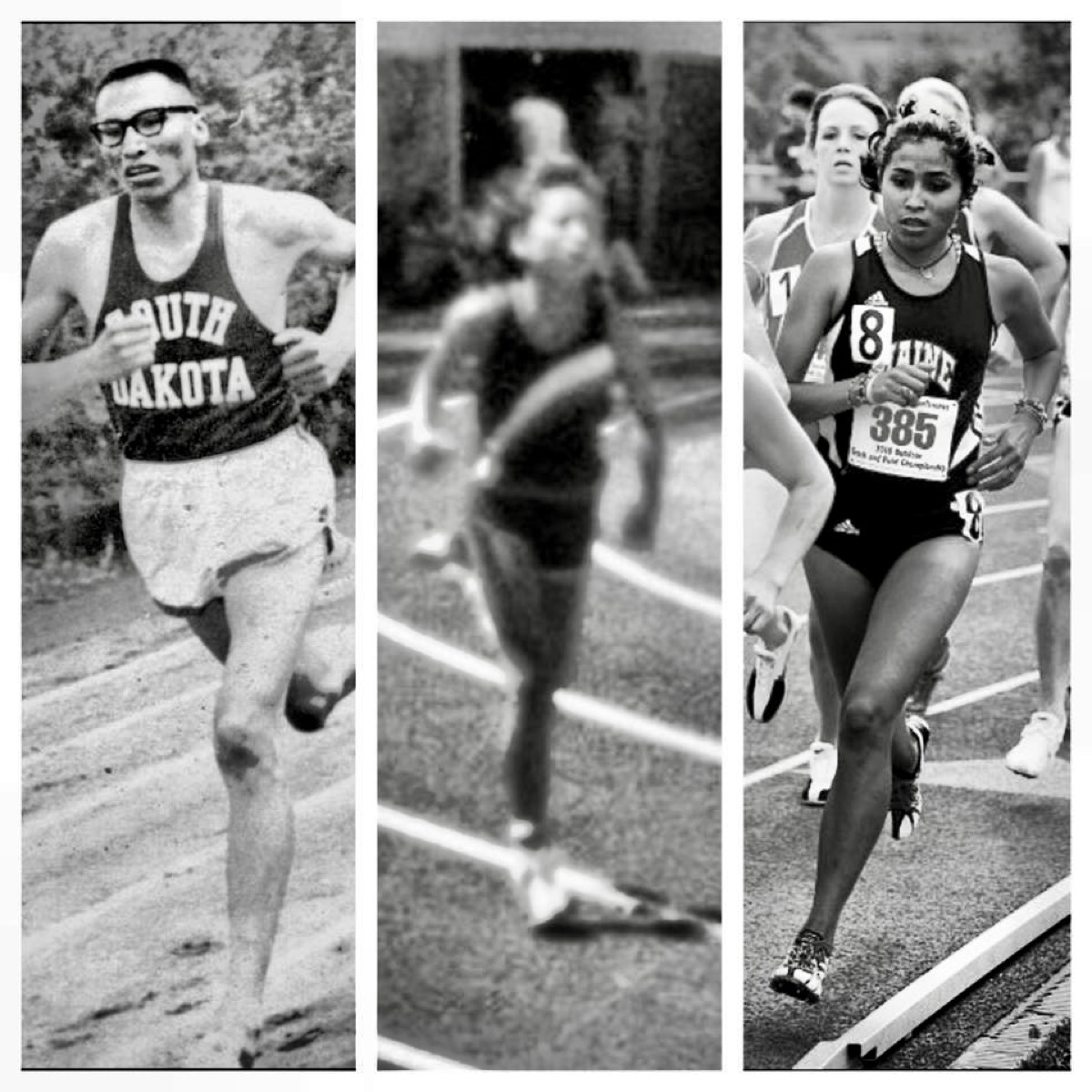

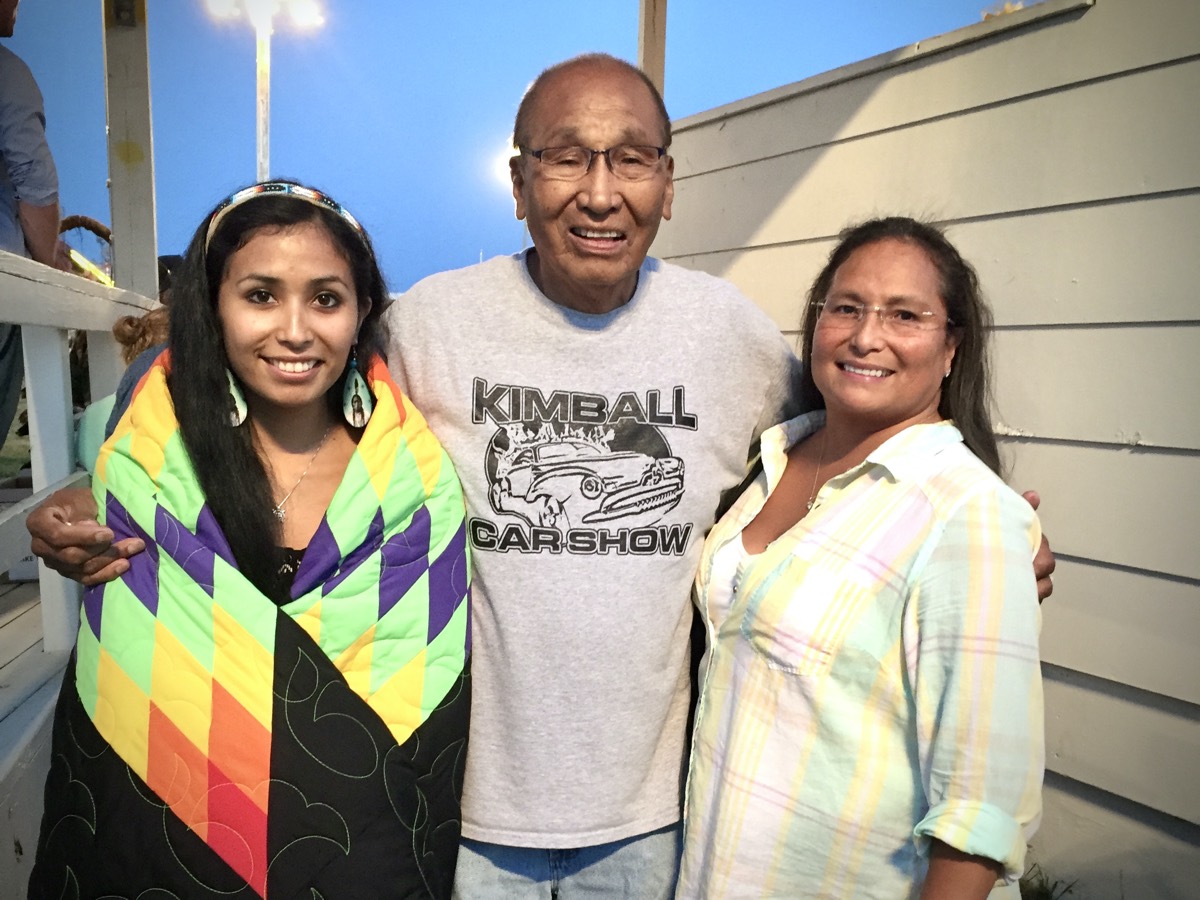

Her grandfather, Nyal Brings Three White Horses, was an accomplished runner accredited with a 4:10 mile, in the 1950s. Her mom, Terra Beth Brings Three White Horses Daniel, was a sprinter. “It’s always been a dream of mine that someone from the family should make it to the Olympic Trials, because my mom and grandfather both tried. They both missed out on those opportunities. My mom was training for 1988 Olympic Trials—her focus was the 400 meters—and I was born that year. I would like to qualify for Olympic Marathon Trials and represent our community and family in that space,” she says. “Running for me has been about culture, legacy, history, and continuing this tradition of our family. It’s connected me so much to my family and our community and also transformed into being about representation of a native athlete,” Daniel says.

Left to right are Nyal Brings Three White Horses, Terra Beth Brings Three White Horses Daniel, and Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel.

When she was a child, Daniel’s dad, David Daniel, accepted a professorship at the University of Maine to teach psychology. Her family moved east, though she continued to visit her extended family in South Dakota each summer. That juxtaposition of her homeland and living in a new community opened her mind. When she was in middle school, she experienced a hate crime. A group of white kids drove by her and a white friend, who were walking together. The harassers called racial slurs, and then got out of the car with brass knuckles, chains, and a pocketknife. Her friend told her to run, and he got beat up. That experience of violent racism made her realize her identity as an indigenous woman living in an inequitable society where people of color are forced to assimilate and are oppressed by white supremacy. Her activism was born from that pain.

“I had this unique perspective of seeing both sides simultaneously, of being able to walk them at the same time. That inspired me to want to make an impact, so that people who are not benefiting from this system can live a better life in the future,” says Daniel. Around that time, she had a dream that she would move to Washington, D.C., to be an advocate, a vision she’d later realize.

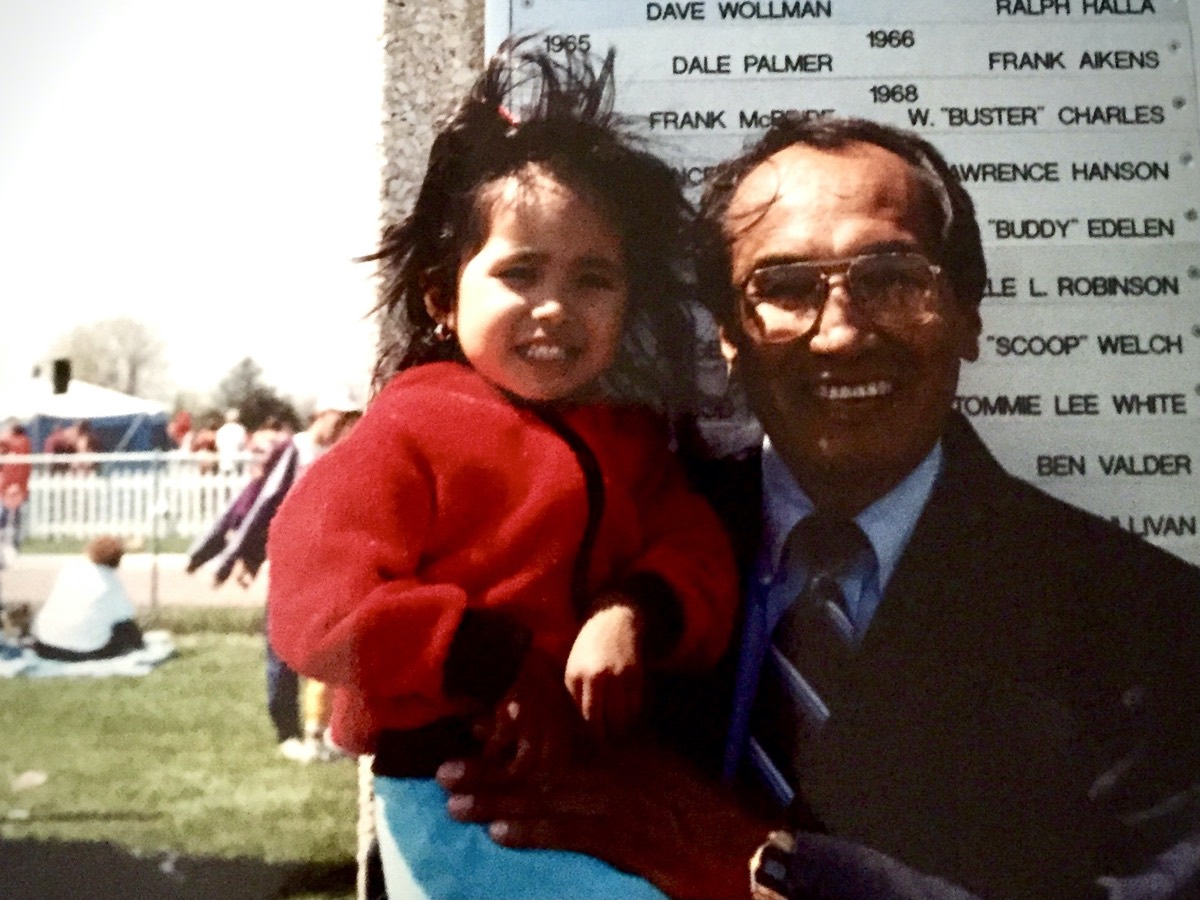

Jordan with her grandfather Nyal when he was inducted into the University of South Dakota Hall of Fame for running.

In high school, Daniel ran track and cross country. Then, while earning a degree in political science at the University of Maine, she competed in Division I track and field at the 1,500-, 3,000-, and 5,000-meter distances. Daniel graduated and, yes, moved to the nation’s capital, in 2013. She worked for various native organizations including a volunteer role with the nonprofit Running Strong. The organization’s mission is to help Native American people meet their immediate survival needs and to support programs that teach self-sufficiency and self-esteem. Running Strong was co-founded by Billy Mills, of the Oglala Lakota Nation, who won a gold medal in the 10,000 meters at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. He’s also a family figure to Daniel.

“Billy is my adoptive grandfather, and he raced against my grandfather. Lala Billy came to his funeral and was a pallbearer and keynote speaker. He’s been a good friend of the family and supported us,” says Daniel. After several years of volunteering for Running Strong, the team invited Daniel to fundraise for the organization and participate in the 2016 Boston Marathon, her first marathon.

Her second marathon was the Boston Marathon in 2019, where she painted her body to raise awareness for the missing and murdered indigenous women (MMIW) crisis. She chose 26 indigenous women and girls, including her cousin, and prayed for each one during her race.

“Loved ones were lost 50 or 60 years ago and their families are still fighting for justice today… I wanted to use the Boston Marathon to give back to those grieving families,” says Daniel.

She held the closing moments of her race in prayer to her grandfather, who passed away from cancer in August of 2016. “My grandfather supported my races from afar. He was a native youth advocate, coach, and tribal-health director. He inspired me to invest in advocacy for Native American youth. If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t be running. I wouldn’t be where I am right now in terms of advocacy and being there for our next generation,” she says.

From left to right are Jordan, Nyal, and Terra Beth at the 2015 Rosebud Wačipi (Rosebud Indian Reservation Annual Powwow).

When she crossed the finish line in 3:02:11, she completed a personal journey but started a brand-new journey via the international attention she and her painted body garnered. Photos of Daniels and her message about the MMIW crisis circulated around the world.

Says Daniel, “The names of those dedicated and this issue at large have been on multiple global platforms and inspired our next generation of athletes, like [indigenous runner and human-rights advocate] Rosalie Fish, who reached out to dedicate her race and paint her body like I had done. She elevated it to an even higher platform,” says Daniel.

Jordan running the 2019 Boston Marathon, with her performance dedicated to the missing and murdered indigenous women (MMIW) humanitarian crisis and her grandfather.

Daniel was putting in hard work off the race courses, too. During the 2017 Occupy Inauguration and Women’s March, Daniel founded Rising Hearts, an indigenous-led organization that elevates indigenous voices through intersectional efforts to end racial, social, climate, and economic injustice.

“I saw a lack of indigenous representation in D.C. when it came to organizing marches, because [those event organizers] weren’t collaborating with indigenous groups,” she says and continues, “There was a lack of representation. It was good intent to organize something to stand in solidarity, but I wanted to push them, and ask questions like, ‘Where were the land acknowledgements? Why didn’t we have indigenous voices on the panel or leading the march?’ Rising Hearts builds connections between groups to work together. It primarily started as grassroots organizing. We’re now focusing on more programmatic work, creating community, [organizing programs] like Indigenous Wellness Through Movement, and other initiatives connected to climate justice, MMIW, and change-your-mascot campaigns.”

Rising Hearts’s Running on Native Lands Initiative is a new program directed at road running, trail running, and ultrarunning with the goals of teaching runners about the first peoples of the lands upon which they run and how to become allies to those peoples. You can learn more on Rising Hearts’s website or in iRunFar’s article.

Jordan speaking at the Water is Life Rally for Standing Rock in Washington, D.C. in 2016. Photo: Jeff Dixon

Any organizations that are interested in allyship and collaboration can use the contact form on the Rising Hearts website. Daniel explains, “Rising Hearts is indigenous led to center indigenous voices—it’s also meant for everybody. We are always cultivating meaningful partnerships and allyship. We’re not just lifting and centering indigenous voices but promoting intersectional growth and to be an ally with other people of color and marginalized communities. To be a good relative in these fights. To be a good supportive role.”

In 2018, Daniel moved from D.C. to Los Angeles, California for a work opportunity, to research and organize around the MMIW epidemic, domestic violence, and sexual assault. “I had accomplished everything and so much more in D.C. than I thought I ever could have. It was the next step,” she says.

Jordan practicing intersectional activism by being an ally to Black people as an indigenous woman running.

California also introduced her to trail running. “My training was focused on road races and is now transitioning more to trail running, in the last two years. That’ll be my bigger focus until the 2024 Olympic Marathon Trials, and then I’ll focus on road. I like trail running more than track. Mentally, I like the longer distances and something that allows me to be outside more and get a better connection and perspective,” she says.

She ran her first trail race in November of 2018, the Into the Wild Limestone Eco Challenge 12k in California. Daniel explains that is was a, “short and fast 12k. I got the course record by five minutes and won. It was the first time that I truly found something fun and it was a different kind of pain. I appreciated the things I got to see on that route. I also had to learn that powerhiking on steep sections is a part of trail racing,” says Daniel. She followed that with the 2019 Into the Wild Fremont Canyon 28k, where she took second in her longest trail race to date.

Daniel says, “I noticed that the trail running community is really outgoing and hilarious—it’s very different from road and track running, which is incredibly competitive. Trail running allows room for goofing off and having conversations while you’re running, because that’s also a part of conserving your energy and allowing yourself to work up those hills. It’s been a lot of fun, and it’s a new challenge. In high school and college, I so much loved cross-country—it was my favorite. Trail running is more difficult and it’s so much more meaningful.”

In addition to Rising Hearts, Daniel is an activist in myriad other ways. To point, she participated in the SLC Air Protectors’s Running as Medicine Indigenous Youth Prayer Run with nine other Native American runners, last September. The crew collectively covered 360 miles from Bears Ears National Monument to Salt Lake City, Utah. She serves on the Intersectional Environmentalist Council.

She’s also collaborating with her life partner, Devin Whetstone, on a photography project dubbed “Not This Time 2020,” to amplify the voices of those who have been impacted by various issues. The first round of portraits captured individuals who’ve been oppressed by racism and climate injustice. “We wanted to portray a sense of urgency. We wanted to call attention to each photo and the need to take care of our planet and mother earth. It’s a way to call to action and raise funds. Every purchase of a portrait will be split between the five organizations that all of our participant models selected, so it’s also a project to build community,” she says. Part two of the photo project will focus on wildfires this year.

Beyond Daniel’s dream of racing in the Olympic Marathon Trials, she would also love to represent her family by racing in USATF trail and mountain running national championships. But overall, her intersectional activism is at the forefront of her athletic goals. She says, “Being able to intersect running with advocacy is the biggest goal.”

Though, advocacy can’t stop with her, Daniel says: “I’m just one person. You have every opportunity to make an impact in your life and in someone else’s life whether it’s big or small—we all have the opportunity to make a ripple effect. Change can start with you.”

Call for Comments

Leave a comment to share a story of working or running with Jordan Marie Daniel, or what you’ve learned from her activism.